Abstract

Importance

To report a family with coexistence of multiple system atrophy (MSA) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) with hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9orf72.

Observations

A 65 year-old woman had a 2-year history of ataxia with autonomic dysfunction but without motor neuron signs. She was diagnosed with MSA based on her clinical history and the hot cross bun sign on brain MRI. Her 62-year-old brother had progressive weakness, fasciculations, hyperreflexia, and active denervation on EMG without cerebellar ataxia. He was diagnosed with ALS. Both patients had a >44/2 hexanucleotide expansion in C9orf72.

Conclusion and Relevance

Patients with hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9orf72 can present with MSA as well as ALS or FTD. We report this family with co-existing MSA and ALS, highlighting the phenotypic variability in neurological presentations with hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9orf72.

Keywords: multiple system atrophy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, neurodegeneration, ataxia, motor neuron disorders

INTRODUCTION

The differential diagnosis of cerebellar ataxia is very broad, with both genetic and non-genetic causes. Non-genetic causes of ataxia include, vascular disease, tumors and paraneoplastic syndrome, alcoholism, and vitamin E deficiencies. Genetic causes of ataxia include autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked or mitochondrial DNA mutations. Genetic testing for ataxia is expensive, and about half of the patients with a family history of ataxia still do not have identifiable mutations in genes that are known to be associated with ataxia.1 In addition, many new ataxia genetic mutations are not yet available for testing in commercial laboratories.

Growing evidence suggests an association between repeat expansion disorders and both cerebellar ataxia and motor neuron diseases. Pathological CAG repeat expansions of ATXN1 usually present as cerebellar ataxia, spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA1); but the large CAG repeat expansion of ATXN1 can present as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)-like disorders.1 Full CAG repeat expansions (>34) in ATXN2 cause SCA22 whereas an intermediate CAG repeat expansion (between 27 and 33) in ATXN2 is a risk factor for ALS.3,4 Another repeat expansion, the GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in C9orf72, has been discovered as the major genetic causes of ALS and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), accounting for 23-46% of familial ALS, 7-24% of familial FTD, as well as approximately 4-7% of sporadic ALS and 3-6% of sporadic FTD.4-6 Interestingly, cerebellar ataxia has been reported in 2 cases with pathological hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9orf72, both with a family history of ALS.7,8 One case had ataxia onset at the age of 20 with hyperreflexia, but no lower motor neuron sign.8 The other case was diagnosed with olivopontocerebellar atrophy (OPCA) with the disease onset at age of 53.7 However, few detailed clinical characteristics in these two cases were described. Here, we present a family with pathological hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9orf72 with the diagnosis of ALS and ataxia, and we describe detailed clinical history, neurological exam, videotapes, and imaging studies. This case history highlights the importance of considering genetic testing for hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9orf72 in ataxia patients with a family history of ALS or dementia.

CASE

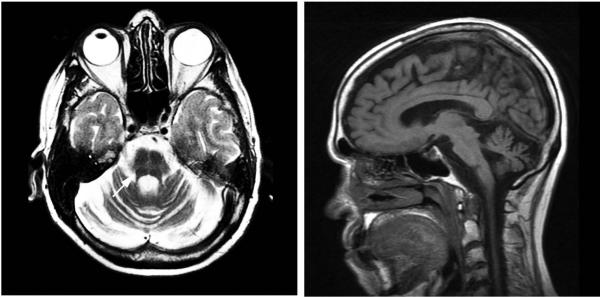

When first seen at our medical center, the patient was a 65-year old woman with a 2-year history of progressive gait ataxia, frequent falling, poor handwriting, cognitive complaints, urinary incontinence, Raynaud 's phenomenon in her toes, orthostatic hypotension, and constipation. She did not take any medications. On examination, her sitting blood pressure was 100/80 mmHg, and her standing blood pressure was 90/60 mmHg. She scored 25/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, losing 2 points in the visuospatial domain (copying the cube and drawing the clock), 1 for language (fluency), 1 for abstraction, and 1 for delayed recall. Her muscle strength was 5/5 throughout without fasciculations. Her reflexes were normal except for absent ankle jerks. Her facial expression was hypomimic and she had 1+ bradykinesia in bilateral hand open-close and finger taps in the Unified Parkinson's disease rating scale (UPDRS). She did not have any rigidity, rest tremor, or spasticity. She had a normal sensory examination. She had prominent scanning speech, dysmetria in bilateral finger-nose-finger test, finger chase, and heel-shin slides. She had impaired fast alternating movements. Her gait was wide-based and unsteady. She was unable to perform tandem gait or stance, and she could not stand on one foot. 35 months later, she fell frequently even with a walker. She could only walked with maximal assistance. She also had short stride length and loss of heel strikes in addition to ataxia (Video 1). Her brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed pontine and cerebellar atrophy with the hot cross bun sign in the T2 weighted images (Figure 1A, B). Autonomic nervous system tests revealed mild neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Urodynamic study confirmed the diagnosis of neurogenic bladder. Her initial nerve conduction study (NCV) and electromyography (EMG) showed normal motor and sensory nerve conduction and no evidence of fasciculation or denervation and repeat EMG 4 years after ataxia symptom onset showed similar findings. More extensive neuropsychological evaluation also performed 4 years after ataxia onset revealed impairment in semantic processing and socio-emotional functioning, consistent with frontotemporal lobe dysfunction, but was too mild to meet the diagnostic criteria of FTD.9 Additionally she displayed some emotional lability. She was diagnosed with possible multiple system atrophy (MSA) based on clinical presentation of ataxia, parkinsonism, autonomic dysfunction, and fast progression.10

Figure 1.

(A) T2 weighted axial MRI of the brain of the 65-year old woman with ataxia showed marked cerebellar degeneration and the hot cross bun sign in the pons (arrow). (B) T1 weighted sagittal MRI of the brain revealed marked pontocerebellar atrophy.

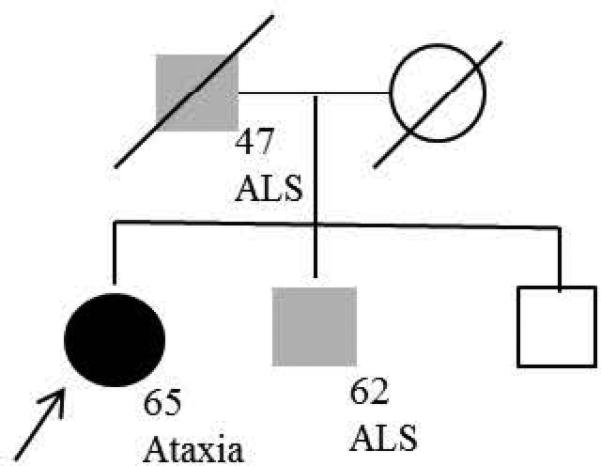

Her family history is shown in Figure 2. Her father developed muscle weakness at the age of 47 and was diagnosed with ALS. He died 2 years later. Her brother also developed muscle weakness and atrophy in his right leg at the age of 62. He developed difficulty in drinking water and right arm weakness 2 months later, when he came to Columbia University for an evaluation. On examination, he had weak tongue strength and tongue atrophy with dysarthria. He had 5/5 arm strength, 3/5 strength in the right hip flexor, 5-/5 strength in the left hip flexor, 4/5 strength in the right hamstring and right tibialis anterior and evertor, 4+/5 strength in the right extensor halluces longus and invertor. His left leg had otherwise 5/5 strength. He had spasticity in all four extremities and fasciculations in the right arm, and in bilateral quadriceps. His reflexes were 3+ at the left biceps and 3+ at the both knees. His plantar responses were flexor bilaterally and he had no jaw jerks. He had bilateral Hoffmann's reflexes. He had a normal finger-nose-finger test. He had spastic gait and slight difficulty in tandem gait. His NCV showed essentially normal motor and sensory nerve conduction studies. EMG revealed diffuse fibrillation and fasciculation potentials in many muscles tested. He was diagnosed with ALS. He did not have any sequence alteration in the familial ALS genes available at the first clinical visit, including SOD1, TARDBP, ANG, FIG4, or FUS assessed by Athena Diagnostics. The patient's condition progressed rapidly and subsequently was treated with tracheostomy and long-term ventilation.

Figure 2.

Family pedigree

Based on our previous report of the diverse presentations of ataxia and motor neuron disease in a family with full CAG repeat expansions of ATXN2 presenting with ataxia and motor neuron disease11, we sent the blood samples to Athena Diagnostics and determined the CAG repeat expansions of ATXN2. The proband had a normal CAG repeat length 22/22 in the ATXN2 gene. Since the hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9orf72 can also either present as ataxia or motor neuron disease,7, 8 we tested this gene. Both the proband and her brother were found to have hexanucleotide repeat expansions of >44/2 in C9orf72. We also performed Southern blot analysis at Columbia University research laboratory to determine the size of hexanucleotide repeat expansions of C9orf72 and found that both the proband and her brother had repeats of more than 1000 with similar expansion size. In addition, we also excluded the COQ2 sequence variant V343A associated with MSA12 and the pathological repeat expansions of SCA3613 in the proband.

DISCUSSION

We present two siblings with ALS and cerebellar ataxia, respectively, and both have pathological hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9orf72. The C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion disease has very diverse clinical presentations, ALS and FTD being the most common.4-6 Parkinsonism and corticobasal syndrome can also occur in patients with C9orf72 repeat expansions.14,15 A study investigating the prevalence of C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions among adult-onset sporadic ataxia patients found only 1 case out of 209 patients carrying this mutation. Interestingly, this patient also had a strong family history of ALS.8 Another reported case of ataxia with a C9orf72 repeat expansion had a clinical diagnosis of OPCA, a variant of MSA, and the patient also had a family history of ALS.7 Our case adds to the literature of C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in a family with both MSA and ALS.

Neuroimaging of patients with C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions show brain atrophy in the various parts of the brains. The cerebellar atrophy is much more common in FTD patients with the C9orf72 expansion than in FTD patients with mutations in other FTD genes, such as MAPT or GRN.16,17 Interestingly, ubiquitin/p62-positive, TDP-43-negative neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in the granular and the molecular layer of the cerebellum have been found to be characteristic of C9orf72 repeat expansion pathology.18 These studies suggested that the cerebellum is commonly involved in the C9orf72 repeat expansion disorders, though clinically, cerebellar ataxia might not be apparent in most cases. Other factors such environmental factors or genetic backgrounds could determine the degree of cerebellar involvement. Interestingly, we found that the proband and her brother had similar size of C9orf72 repeat expansions, which indicate that other genetic modifiers or environmental factors might partly account for the phenotype variability.

In conclusion, C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion disease can have diverse clinical presentations, including ALS, FTD, and cerebellar ataxia. The exact prevalence of C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions in ataxia patients with a family history of ALS has not been investigated, but clinicians might consider such genetic tests in this specific population.

Supplementary Material

Video 1: The 65 year-old woman with ataxia demonstrated scanning speech, dysmetria in the finger-nose test, slow and irregular rapid alternating movements, and irregular knee-shin slides. She also had Raynaud's phenomenon in her hand and toes. While walking, she had wide-based gait and irregular footsteps with short stride length and no heel strikes.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Dr. Kuo received funding from NIH (K08 NS083738), Louis V. Gerstner Jr Scholar Award, Parkinson's Disease Foundation, American Academy of Neurology Research Fellowship, and American Parkinson's Disease Association.

Dr. Mitsumoto received funding from NIH (R01-ES016348), Spastic Paraplesia Foundation, Muscular Dystrophy Association

Jill Goldman received funding from NIA/NIH (P50 AG08702 PI Shelanski), NINDS/NIH (R01NS076837-01A1 PI Huey), Parkinson's Disease Foundation

Dr. Cosentino is funded by NIH/NINDS (R01NS076837) and NIH/NIA (P50AG008702)

Dr. Huey is funded by NIH/NINDS (R01NS076837, R00NS060766), Florence and Herbert Irving Clinical Research Career Award, NIH/NIA (P50AG008702), NIH/NIA (R01AG041795), NIH/NIA (R0103873402).

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have reported no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dürr A. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: polyglutamine expansions and beyond. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(9):885–894. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pulst SM, Nechiporuk A, Nechiporuk T, et al. Moderate expansion of a normally biallelic trinucleotide repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Nat Genet. 1996;14(3):269–276. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elden AC, Kim HJ, Hart MP, et al. Ataxin-2 intermediate-length polyglutamine expansions are associated with increased risk for ALS. Nature. 2010;466(7310):1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature09320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron. 2011;72(2):245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALSFTD. Neuron. 2011;72(2):257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majounie E, Renton AE, Mok K, et al. Frequency of the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(4):323–330. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70043-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindquist SG, Duno M, Batbayli M, et al. Corticobasal and ataxia syndromes widen the spectrum of C9ORF72 hexanucleotide expansion disease. Clin Genet. 2013;83(3):279–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fogel BL, Pribadi M, Pi S, Perlman SL, Geschwind DH, Coppola G. C9ORF72 expansion is not a significant cause of sporadic spinocerebellar ataxia. Mov Disord. 2012;27(14):1832–1833. doi: 10.1002/mds.25245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011 Sep;134(Pt 9):2456–77. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy Neurology. 2008;71(9):670–676. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000324625.00404.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tazen S, Figueroa KP, Kwan JY, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 in a family with full CAG repeat expansions of ATXN2. JAMA Neurol. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.443. Published online August 19, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Multiple-System Atrophy Research Collaboration. Mutations in COQ2 in familial and sporadic multiple-system atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 18;369(3):233–244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi H, Abe K, Matsuura T, et al. Expansion of intronic GGCCTG hexanucleotide repeat in NOP56 causes SCA36, a type of spinocerebellar ataxia accompanied by motor neuron involvement. Am J Hum Genet. 2011 Jul 15;89(1):121–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boeve BF, Boylan KB, Graff-Radford NR, et al. Characterization of frontotemporal dementia and/or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated with the GGGGCC repeat expansion in C9ORF72. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 3):765–783. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snowden JS, Rollinson S, Thompson JC, et al. Distinct clinical and pathological characteristics of frontotemporal dementia associated with C9ORF72 mutations. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 3):693–708. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahoney CJ, Downey LE, Ridgway GR, et al. Longitudinal neuroimaging and neuropsychological profiles of frontotemporal dementia with C9ORF72 expansions. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2012;4(5):41. doi: 10.1186/alzrt144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, Boeve BF, et al. Neuroimaging signatures of frontotemporal dementia genetics: C9ORF72, tau, progranulin and sporadics. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 3):794–806. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mori K, Weng SM, Arzberger T, et al. The C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat is translated into aggregating dipeptide-repeat proteins in FTLD/ALS. Science. 2013;339(6125):1335–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.1232927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video 1: The 65 year-old woman with ataxia demonstrated scanning speech, dysmetria in the finger-nose test, slow and irregular rapid alternating movements, and irregular knee-shin slides. She also had Raynaud's phenomenon in her hand and toes. While walking, she had wide-based gait and irregular footsteps with short stride length and no heel strikes.