Abstract

We report the first case series from Africa and the Middle East on choledochal cyst, a disease which shows significant geographical distribution with high incidence in the Asian population. In this study, the epidemiological data of the patients are presented and analyzed. Attention was paid to diagnostic imaging and its accuracy in the diagnosis and classification of choledochal cyst. Most cases of choledochal cyst disease have type I and IV-A cysts according to the Todani classification system, which support the etiological theories of choledochal cyst, especially Babbitt’s theory of the anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct junction, which are clearly stated. The difficulties and hazards of surgical management and methods used to avoid operative complications are clarified. Early and late postoperative complications are also included. This study should be followed by multicenter studies throughout Egypt to help assess the incidence of choledochal cysts in one of the largest populations in Africa and the Middle East.

Keywords: Choledochal cyst, Hepatic cyst, Hepaticojejunostomy, Caroli disease, Hepatectomy

Core tip: The research reported in this manuscript represents 20 years of experience in a single high volume Egyptian center and includes 50 cases of choledochal cyst. This is the first report of a case series from Africa and the Middle East.

INTRODUCTION

Choledochal cysts are disproportionate dilatations of the biliary system[1]. The incidence of choledochal cysts shows significant geographic variation, being higher in the Asian population and reaching up to 1 in 1000[2]. Complete excision of the cyst is the best treatment strategy to avoid long-term complications especially malignant transformation, recurrent cholangitis and gallstones[2,3]. To our knowledge, there are no studies on choledochal cysts from Africa or the Middle East region to assess the local prevalence of the disease. In this study, we report 20 years of single Egyptian tertiary center experience in 50 cases of choledochal cyst with a focus on the etiological, clinical and surgical implications according to the findings in this case series.

CASE REPORT

This is a retrospective study of all patients admitted to Mansoura Gastrointestinal Surgical Center during the period from January 1991 to November 2012. Data were retrieved from the internal web-based Ibn Sina registry system supplemented by paper-based records. Data were collected and rearranged in a standardized manner. Choledochal cysts were classified according to the Todani modification of the Alonoso-Lej classification[4]. Early and late complications were noted.

The Shapiro-Wilk test is used to assess normality of the data. Numerical data are presented as means and standard deviations or as medians with ranges. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS v20.

In total, 50 patients (39 females, 11 males, ratio 3.5:1) were admitted to our center during the study period. Data on 2 female patients were lost from the medical records and one female patient refused to undergo surgery. The mean age at presentation was 265 ± 207.7 mo ranging from 3 mo to 65 years. Right hypochondrial pain was the most common presenting symptom (n = 45%-93.8%) followed by jaundice (n = 28%-58.3%), vomiting (n = 23%-47.9%), recurrent fever (n = 21%-43.8%) and abdominal mass (n = 4%-8.3%). The classic triad of abdominal pain, jaundice and palpable right upper quadrant mass was identified in one patient.

Five patients underwent previous biliary surgery during which choledochal cysts were not detected. Three of the five cases underwent cholecystectomy, and two cases underwent exploration for abdominal cysts which were not operated on. Moreover, one case was explored for acute abdomen which was mostly attributed to perforated duodenal ulcer, but the exploration was negative and the patient improved under conservative treatment. Choledochal cysts were associated with congenital anomalies in 5 cases (10.4%); ventricular septal defect (one case), medullary sponge kidney (one case), multiple bilateral renal cortical cysts (one case), congenital megacolon (one case), and intestinal malrotation (one case).

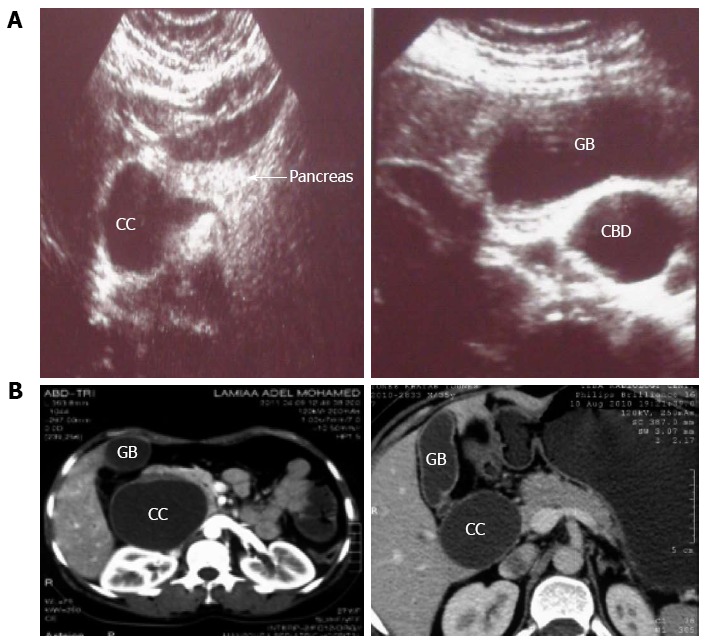

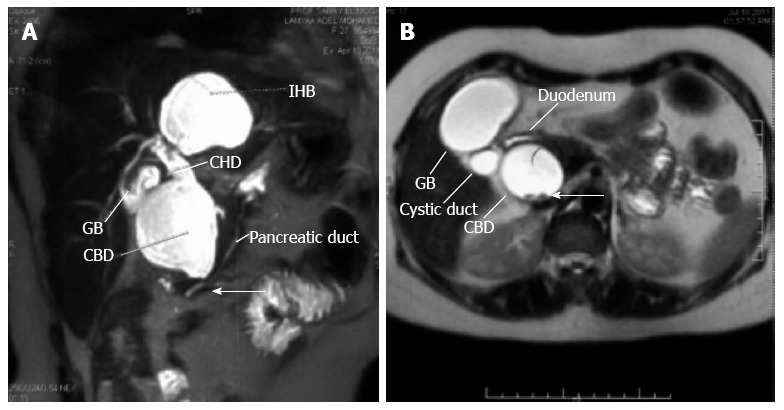

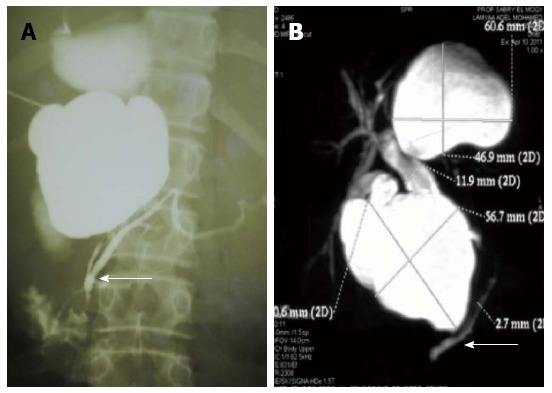

In our series, abdominal ultrasound (US) was performed in 38 cases; diagnosed 19 cases (50%) and accurately classified the cyst type in 11 cases (28.8%) (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was performed in 41 cases; diagnosed 38 cases (92.7%) and accurately classified the cyst type in 36 cases (87.8%) (Figure 2). Anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct junction (APBDJ) was detected by preoperative cholangiography in 6 cases (14.6%), 5 cases by MRCP and one case by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (Figure 3). According to the Todani modification of the Alonso-Lej classification, we identified patients with type Ia (n = 29%-60.4%), type Ib (n = 2%-4.2%), type Ic (n = 4%-8.3%), type IV-A (n = 12%-25%) and type V (n = 1%-2.1%) choledochal cyst. Table 1 shows a comparison between the results of our study and other studies from countries in South East Asia including patient demographic data, clinical presentation and cyst classification.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound imaging and abdominal computed tomography of type I choledochal cyst. A: Ultrasound imaging; B: Abdominal CT. CC: Choledochal cyst; GB: Gall bladder; CBD: Common bile duct; CT: Computed tomography.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography images of choledochal cyst. A: Type IV-A choledochal cyst with anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct junction (white arrow); B: Type I choledochal cyst with multiple stones inside (white arrow). IHB: Intrahepatic biliary radicals; CHD: Common hepatic duct; GB: Gall bladder; CBD: Common bile duct.

Figure 3.

Anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct junction detected by cholangiography (white arrow). A: Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography of type IV-A choledochal cyst; B: MRCP of type IV-A choledochal cyst. MRCP: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.

Table 1.

Comparison between our study and other studies from South East Asia

| Shi et al[5] (2001) | She et al[6] (2009) | Shah et al[7] (2009) | Woon et al[8] (2006) | Our study (2013) | |

| Country | China | Hong Kong | Kashmir | Singapore | Egypt |

| Total number | 108 | 83 | 79 | 32 | 50 |

| Sex | 85:23 | 60:23 | 67:22 | 25:7 | 39:11 |

| (F:M) | Ratio 3.7:1 | Ratio 2.6:1 | Ratio 3:1 | Ratio 3.5:1 | Ratio 3.5:1 |

| Age | |||||

| Mean | 27.8 yr | 45 mo | NR | 41 yr | 265 d |

| Range | 3-68 yr | 0-16 yr | 18-74 yr | 3 mo-65 yr | |

| Presentation | |||||

| Pain | (61%-56.5%) | (39%-46.9%) | (58%-73.4%) | (29%-91%) | (45%-93.8%) |

| Jaundice | (77%-71.3%) | (35%-42.2%) | (26%-32.9%) | (13%-41%) | (28%-58.3%) |

| Vomiting | NO | (26%-31.3%) | NO | (12%-38%) | (23%-47.9%) |

| Fever | (61%-56.5%) | NO | NO | (11%-34%) | (21%-43.8%) |

| Mass. | NO | NO | (20%-25.3%) | (8%-25%) | (4%-8.3%) |

| Triad | NO | (2%-2.4%) | (17%-21.5%) | (4%-13%) | (1%-2%) |

| Incidental | NO | NO | (7%-8.9%) | (3%-9%) | NO |

| Classification | |||||

| I | (75%-69.4%) | (53%-67.9%) | (54%-68.3%) | (27%-84.4%) | (35%-72.9%) |

| II | NO | (4%-5.1%) | NO | (2%-6.2%) | NO |

| III | (1%-0.9%) | (2%-2.6%) | NO | NO | NO |

| IV | (24%-22.2%) | (15%-19.2%) | (21%-26.6%) | (2%-6.2%) | (12%-25%) |

| V | (6%-5.6%) | (4%-5.1%) | (4%-5%) | (1%-3.1%) | (1%-2.1%) |

| Unclassified | (2%-1.8%) | (5%-6.1%) | NO | NO | NO |

| APBDJ | NR | NR | (21%-26.6%) | NR | (6%-14.6%) |

NR: Not reported; APBDJ: Anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct junction.

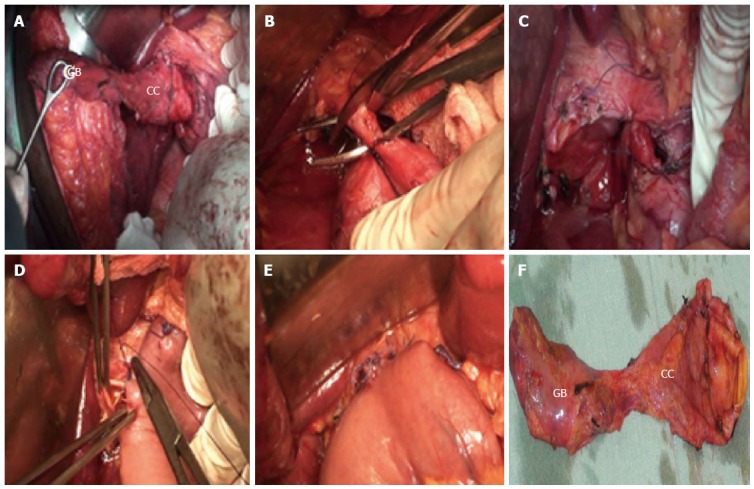

Thirty eight patients underwent cyst excision and hepatico-jejunostomy Roux-en-Y (Figure 4), one case underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy due to intrapancreatic extension of the cyst, 3 cases of type IV-A underwent left hepatectomy, extrahepatic biliary resection and right hepatico-jejunostomy Roux-en-Y. Five cases underwent internal drainage procedures via cysto-duodenostomy in 3 cases and cysto-jejunostomy in 2 cases. Of the surgical cases, a mass was detected in the cyst wall in one case and its malignant nature was confirmed by intraoperative frozen section.

Figure 4.

Surgical excision of choledochal cyst. A: Exposure of type IA choledochal cyst; B: Division of biliary system at the carina proximal to the cyst; C: The biliary system after excision of the cyst; D, E: Restoration of biliary continuity by hepaticojejunostomy; F: The specimen after complete excision of the cyst consisting of gall bladder (GB) and choledochal cyst (CC).

Early postoperative complications included postoperative wound disruption (n = 1) that was managed surgically; collections (n = 4) 3 managed conservatively, and 1 with ultrasound guided tube drainage; biliary leakage (n = 3) that was managed conservatively, pancreatic leakage (n = 1) that was managed conservatively, internal hemorrhage on top of acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis that was managed surgically (n = 1), and air embolism (n = 1). The overall early complication rate was 23.4%. There was no early postoperative mortality.

The median follow-up period was 55 ± 38.3 mo (mean ± SE). Late postoperative complications included intrahepatic duct stones (n = 2%-4.3%), anastomotic stricture (n = 1%-2.1%), liver abscess (n = 2%-4.3%) and hepatic malignancy (n = 1%-2.1%). The overall late complication rate was 12.8%. There were 2 late postoperative mortalities. One died 3 years after surgery due to bilobar liver abscesses. The other, with confirmed malignant transformation by intraoperative frozen section, died 7 mo after surgery with recurrent tumor in segment IV of the liver.

DISCUSSION

In our experience, most cases of choledochal cyst (64.6%) were diagnosed after the first decade of life. This increased incidence in adults may be attributed to institutional referral bias. However, increased incidence in adults has been reported in many case series of both children and adults[5,9]. This increase is justified, according to some authors, by the advance in hepatobiliary imaging techniques[7]. The possibility of choledochal cyst should be kept in mind during surgical exploration in all patients with biliary tract-related symptoms. In our series, 5 cases (10.4%) had undergone previous biliary surgery and choledochal cysts were unnoticed during the surgery.

The most accepted theory in explaining the pathogenesis of choledochal cyst is Babbitt’s theory of the APBDJ precluding normal sphincter development at the APBDJ. This anomalous junction leads to reflux of pancreatic secretions into the common bile duct due to the smaller diameter and higher pressure of the pancreatic duct. This theory is supported by radiological detection of APBDJ or by a high level of amylase in the cyst fluid[10]. In our series, APBDJ was detected in 6 cases (14.6%) (Figure 3), but unfortunately amylase cyst fluid is not routinely performed in our center. In addition, the presence of five cases of choledochal cyst (10.4%) with associated congenital anomalies supports other etiological theories of a congenital background[11]. These associations give rise to the necessity of a thorough evaluation of patients with choledochal cysts to exclude associated congenital diseases for safe surgical and anesthetic considerations[12].

The so-called classic triad of intermittent jaundice, abdominal mass, and pain was found in a minority of cases according to most case series[13]. The most frequently seen presentation was abdominal pain (93.8%) which is a nonspecific symptom and usually associated with a relatively late diagnosis. On the other hand, jaundice was the second most common presentation (58.3%), and it was usually associated with early diagnosis. These clinical findings were corroborated by other studies[6,14].

For any case with biliary symptoms, abdominal ultrasound scan is the initial imaging modality of choice. Precise and accurate delineation of the biliary system mandates cholangiography with the advantage of non-invasive MRCP over endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography[1,11]. In our experience, abdominal US diagnosed 19 cases (50%) and accurately classified the cyst type in 11 cases (28.8%), while MRCP diagnosed 38 cases (92.7%) and accurately classified the cyst type in 36 cases (87.8%). These findings were consistent with other studies[2,14,15].

Based on the Todani modification of the Alonso-Lej classification, we found 35 cases of type I (72.9%), and 12 cases of type IV-A (25%) making a total of 97.9% with choledochal cysts. This supports the criticism of this standard classification scheme describing it to be misleading, purposeless, and thus it should be abandoned to reserve the term congenital choledochal cyst for congenital extrahepatic or intrahepatic biliary duct dilatation apart from Caroli’s disease, choledochocele and diverticulum of the common bile duct[16].

Consensus has established that the best treatment for choledochal cysts is surgical excision whenever possible. This helps to avoid long-term complications of the cyst including pancreatitis, cholangitis, choledocholithiasis, biliary cirrhosis and malignant transformation. To achieve complete cyst excision, accurate recognition of the beginning and the termination of the cyst is mandatory[17].

Dissection towards the lower end of the cyst may require pancreaticoduodenectomy in favor of complete cyst excision; otherwise inevitable unplanned pancreatic duct injury would occur. In our experience, one case was complicated by postoperative pancreatic leakage that was managed conservatively, one case was planned for pancreaticodoudenectomy, and one case had an accidental pancreatic duct injury that was managed by pancreaticoduodenostomy over external stent, but later this case was readmitted due to acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis and was explored and managed by external pancreatic duct tube reposition. Diao et al[18] performed choledochal cyst excision without ligation of the distal stenotic stump in 207 patients and there was no significant difference in the results compared to the ligated group of patients. This technique helped to decrease the incidence of pancreatic injury which was reported to be 2%-6% in previous reports from China. A probe inserted into the pancreatic duct through a duodenotomy may help to prevent pancreatic duct injury in difficult cases[19].

Dissection towards the upper end of the cyst should be performed considering measures to avoid postoperative anastomotic stricture. The best strategy is to resect at the level of the carina with left duct spatulation to obtain a wide stoma for the anastomosis. However, a significant therapeutic challenge is present with a dilated biliary system above the carina. Complete excision in such cases may put the surgeon in the situation of performing two to four duct anastomoses with normal caliber ducts. Although all portions of choledochal cysts should be removed, residual proximal cyst walls may be left to facilitate biliary anastomosis[20]. Some cases may require hepatectomy or liver transplantation.

Limitations of this study were the absence of institutional referral bias to our center making it difficult to compare the incidence of choledochal cysts in adults compared to children. Also, the absence of emergency referral to our center prevents the study of emergent presentation of the disease as spontaneous perforation and acute pancreatitis. However, this study needs to be followed by multicenter studies throughout Egypt to help assess the incidence of choledochal cysts in one of the largest populations in Africa and the Middle East.

Choledochal cysts are disproportionate dilatations of the biliary system[1]. They can present at different ages with variable biliary symptoms. Thus, a high sense of suspicion for the disease is required. Most cases of choledochal cyst disease have type I and IV-A cysts. If left untreated, choledochal cysts have an increased risk of malignant transformation. Early surgical excision and restoration of biliary tract continuity is mandatory, whatever the symptom severity to avoid long-term complications whenever possible[20].

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Liu JR, Liem NT, Tian XF S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Lee HK, Park SJ, Yi BH, Lee AL, Moon JH, Chang YW. Imaging features of adult choledochal cysts: a pictorial review. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:71–80. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2009.10.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hung MH, Lin LH, Chen DF, Huang CS. Choledochal cysts in infants and children: experiences over a 20-year period at a single institution. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:1179–1185. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1429-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu SL, Li L, Hou WY, Zhang J, Huang LM, Li X, Xie HW, Cheng W. Laparoscopic excision of choledochal cyst and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy in symptomatic neonates. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:508–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts: Classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;134:263–269. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi LB, Peng SY, Meng XK, Peng CH, Liu YB, Chen XP, Ji ZL, Yang DT, Chen HR. Diagnosis and treatment of congenital choledochal cyst: 20 years’ experience in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:732–734. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i5.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.She WH, Chung HY, Lan LC, Wong KK, Saing H, Tam PK. Management of choledochal cyst: 30 years of experience and results in a single center. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:2307–2311. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah OJ, Shera AH, Zargar SA, Shah P, Robbani I, Dhar S, Khan AB. Choledochal cysts in children and adults with contrasting profiles: 11-year experience at a tertiary care center in Kashmir. World J Surg. 2009;33:2403–2411. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woon CY, Tan YM, Oei CL, Chung AY, Chow PK, Ooi LL. Adult choledochal cysts: an audit of surgical management. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:981–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singham J, Schaeffer D, Yoshida E, Scudamore C. Choledochal cysts: analysis of disease pattern and optimal treatment in adult and paediatric patients. HPB (Oxford) 2007;9:383–387. doi: 10.1080/13651820701646198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babbitt DP. [Congenital choledochal cysts: new etiological concept based on anomalous relationships of the common bile duct and pancreatic bulb] Ann Radiol (Paris) 1969;12:231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramnarine IR, Mulpur AK, McMahon MJ, Thorpe JA. Pleuro-biliary fistula from a ruptured choledochal cyst. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19:216–218. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(00)00632-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singham J, Yoshida EM, Scudamore CH. Choledochal cysts: part 2 of 3: Diagnosis. Can J Surg. 2009;52:506–511. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Vries JS, de Vries S, Aronson DC, Bosman DK, Rauws EA, Bosma A, Heij HA, Gouma DJ, van Gulik TM. Choledochal cysts: age of presentation, symptoms, and late complications related to Todani’s classification. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1568–1573. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.36186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delaney L, Applegate KE, Karmazyn B, Akisik MF, Jennings SG. MR cholangiopancreatography in children: feasibility, safety, and initial experience. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:64–75. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0644-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tipnis NA, Werlin SL. The use of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in children. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:225–229. doi: 10.1007/s11894-007-0023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Visser BC, Suh I, Way LW, Kang SM. Congenital choledochal cysts in adults. Arch Surg. 2004;139:855–60; discussion 860-2. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.8.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho MJ, Hwang S, Lee YJ, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Moon DB, Lee SK, Kim MH, Lee SS, Park DH, et al. Surgical experience of 204 cases of adult choledochal cyst disease over 14 years. World J Surg. 2011;35:1094–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diao M, Li L, Cheng W. Is it necessary to ligate distal common bile duct stumps after excising choledochal cysts? Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:829–832. doi: 10.1007/s00383-011-2877-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolb A, Kleeff J, Frohlich B, Werner J, Friess H, Büchler MW. Resection of the intrapancreatic bile duct preserving the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:31–34. doi: 10.1007/s00534-008-0013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edil BH, Cameron JL, Reddy S, Lum Y, Lipsett PA, Nathan H, Pawlik TM, Choti MA, Wolfgang CL, Schulick RD. Choledochal cyst disease in children and adults: a 30-year single-institution experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:1000–105; discussion 1000-105;. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]