Abstract

The cytochromes P450 (CYPs) play a central role in a variety of important biological oxidations, such as steroid synthesis and the metabolism of xenobiotic compounds, including most drugs. Because CYPs are frequently assayed as drug targets or as anti-targets, tools that provide confirmation of active-site binding and information on binding orientation would be of great utility. Of greatest value are assays that are reasonably high throughput. Other heme proteins, too—such as the nitric oxide synthases (NOSs), with their importance in signaling, regulation of blood pressure, and involvement in the immune response—often display critical roles in the complex functions of many higher organisms, and also require improved assay methods. To this end, we have developed an analog of cyanide, with a 13CH3-reporter group attached to make methyl isocyanide. We describe the synthesis and use of 13C-methyl isocyanide as a probe of both bacterial (P450cam) and membrane-bound mammalian (CYP2B4) CYPs. The 13C-methyl isocyanide probe can be used in a relatively high-throughput 1-D experiment to identify binders, but it can also be used to detect structural changes in the active site based on chemical shift changes, and potentially nuclear Overhauser effects between probe and inhibitor.

Keywords: NMR, Heme, P450cam, CYP2B4, Screening

1 Introduction

Mammalian cytochromes P450 (CYPs) are the enzymes primarily responsible for drug and xenobiotic metabolism in humans, so have been of particular interest in the pharmaceutical industry. They are relatively large membrane-bound proteins with molecular mass of ~65 kDa (1). Accordingly, despite some recent successes, it is difficult to obtain structural information on the mammalian CYPs, either via X-ray or current multidimensional NMR techniques. And the X-ray structures that have been reported of mammalian CYPs are of proteins that lack the membrane-binding N-terminal region and have other solubilizing mutations (2-5).

Studies of an additional group of heme proteins, like the above mentioned NOSs, though they may already have had their crystal structures determined, could benefit from the development of a quick and reliable assay that could enable unambiguous screening for potential binders or inhibitors of these proteins in either a primary or secondary assay. Clearly, there is a need for improved techniques that rapidly probe at least part of the active-site structure, and better define binding interactions with substrates or inhibitors for heme proteins. With this goal in mind, we have capitalized on the fact that cyanide is a promiscuous ligand for heme iron (binding through its carbon), and that alkyl isocyanides (alkyl-NC) are known to be ligands for a number of heme proteins (6, 7). The absorption spectra of the alkyl isocyanide-bound heme proteins are typical of type-II binding spectra, where the heme Soret band is shifted upon binding of the alkyl isocyanide, with maxima at 430 and/or 455 nm, depending upon the extent of back-bonding from iron into the triple bond of the isonitrile. In fact, resonance Raman experiments (6, 7) have shown that the heme-bound isocyanide binds in two conformations, either linear or bent, depending on C–Fe bond order. These two conformations are expected to be in fast exchange on the NMR timescale, but slow exchange on the resonance Raman timescale. The two orientations are shown in Fig. 1 for the methyl isocyanide ligand, which is the probe described in this chapter. The linear and bent forms are related to the resonance structures of methyl isocyanide (Fig. 2), although the imine is unfavored because of electron donation that stabilizes it via formation of a dative bond (as in Fig. 1, where electron donation is via back-bonding from iron). Alkyl isocyanides bind strongest when the heme iron is reduced (Kd× 10-5–10-6 M), although with increasing alkyl chain length, even the ferric form can bind with a micromolar range dissociation constant (8). The previously established utility of 13CH3-methyl probes for NMR structural and dynamical studies in large proteins (9-11) is what led to our interest in developing 13CH3-based alkyl isocyanides as probes for heme proteins, focused on the simplest member of this family, methyl isocyanide (13CH3NC). As the smallest member of the alkyl isocyanide family, methyl isocyanide is least likely to interfere with substrate or inhibitor binding (being only slightly larger than dioxygen, the natural ligand). The 13C-label enables selective observation of the attached methyl protons, providing both 1H and 13C chemical-shift perturbation probes of structural (and potentially dynamical) changes in the binding pocket, due to substrate or inhibitor binding. And the lack of adjacent methylene protons in 13CH3NC avoids dipolar relaxation, which would produce line broadening. Furthermore, the rapidly rotating methyl group has a short internal correlation time, even when bound to a large heme protein, so the proton line width will be narrow, like that of a small molecule.

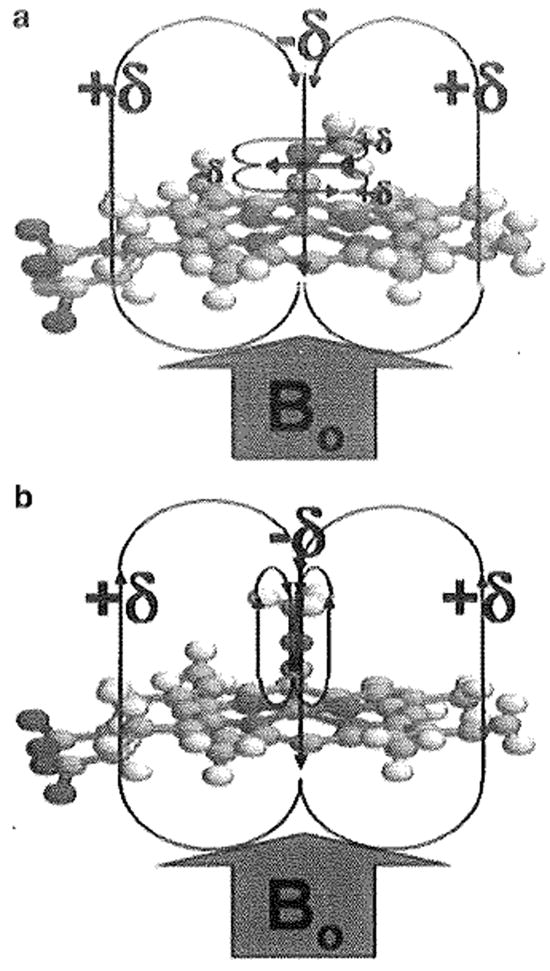

Fig. 1.

Methyl isocyanide bound to heme iron. Representation of methyl isocyanide bound to the iron of the heme with (a) an iron–carbon bond order of two (“bent”) and (b) an iron–carbon bond order of one (“linear”). The pyrrole rings and the CN triple (or double) bond produce a very anisotropic environment capable of producing large chemical-shift perturbations for the labeled methyl of 13CH3NC

Fig. 2.

Resonance structures for 13CH3NC, methyl isocyanide

Together, these various features of the 13CH3NC probe allow it to serve as a sensitive structural probe of the heme active site in experiments such as 2-D 1H-13C HSQC (heteronuclear single-quantum coherence) and 13C-filtered 1H 1D (10, 12) which, given the large size of CYP enzymes, especially when complexed to micelles, would not normally be feasible. Herein, we present the synthesis and application of this 13C-methyl isocyanide probe.

2 Materials

Prepare all solutions using deionized water and analytical grade reagents. Prepare and store all reagents at room temperature (unless indicated otherwise). Diligently follow all waste disposal regulations when disposing of waste materials.

2.1 Synthesis of 13C-Methyl Isocyanide

13C-Methyliodide, a liquid (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories).

Silver cyanide salt (Sigma).

8 M potassium cyanide solution, purchased as a salt (Sigma) and dissolved in water.

Thick-walled (approx 1 in.) glass tube.

Acetylene torch to seal glass tube.

Mineral oil and hot plate.

Vacuum distillation apparatus.

Bulb-to-bulb distillation apparatus.

2.2 Sample Preparation of 13C-Methyl Isocyanide-Bound Protein

Tank of argon gas.

Pure 13C-Methyl isocyanide, as prepared above.

300–500 μL of 75–100 μM solution of CYP450 or heme protein in PBS buffer comprised of 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 2.0 mM KH2PO4 (PH7.4). Concentration determined using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer. Protein solution stored short term at 4°C. For long-term storage (>l week) flash freeze in liquid nitrogen and Store at −80°C.

Fresh, solid sodium dithionite (Sigma). Stored under argon in a parafilm-sealed tube to prevent premature oxidation (see Note 1).

Rubber hose, hose/needle metal adapter, two needles—one long and one short—and NMR tube-sized rubber septum.

Optional: UV–Vis spectrophotometer such as CARY 50 BIO UV–Vis spectrophotometer.

5 mm thin-walled glass NMR tube with plastic NMR tube cap (Norell).

2.3 Collection of NMR Data

Medium- to high-field NMR spectrometer such as a 500 or 600 MHz Varian Inova spectrometer.

Sample as prepared above.

3 Methods

Carry out all procedures at room temperature or 25°C unless otherwise specified.

3.1 Synthesis of 13C-Methyl Isocyanide

Mix 1 mmol of 13C-methyliodide and 2 mmol of silver cyanide, to form a solution/suspension, in a thick-walled glass tube so that the glass tube is about ¾ full (13).

Seal the glass tube to create a closed system by using an acetylene torch to melt and fuse the glass at open end of glass tube.

Heat the mixture for 1 h at 95°C in a mineral oil bath, which is being warmed on a hot plate in a closed fume hood. Be sure to exercise caution, work in hood and wear protective eye wear when working with sealed tubes.

Cool the tube to room temperature slowly; when cool, break tube carefully (etch glass) at one end to open it, and quench reaction for 12 h by adding 5 mL of 8 M KCN solution and mixing carefully to decompose resulting complex. Exercise extreme caution in working with cyanide solutions, and in disposal of excess KCN solution (see Note 2).

Distill the quenched mixture under vacuum to obtain the initial crude 13C-methyl isocyanide.

Follow the initial vacuum distillation by a second purification step, of bulb-to-bulb distillation, using a rotary evaporator. Yield should be close to 21%.

Purity can be confirmed by taking a 1H-NMR spectrum in d4-methanol. Spectrum Should look like Fig. 3, with the 1:1:1 triplet of the doublet of triplets confirming the identity of the compound to be that of 13C-methyl isocyanide, as opposed to 13C-methyl-labeled acetonitrile (due to the 2J-coupling between the quadrupolar 14N and the methyl protons) (see Note 3).

Store at −80°C in sealed container when not in use, to prevent vaporization of this volatile compound.

Fig. 3.

NMR spectrum of 13CH3NC in d4-methanol. The 13C-coupled 1H resonances of 13CH3NC are located on either side Of the solvent resonance. The inset shows the additional splitting (1:1:1 triplet) of the two 13C-split proton resonances. This triplet is from the 2J-coupling between the quadrupolar 14N nucleus (I= 1) and the methyl Protons. The spectrum was acquired at 300 MHz

3.2 Sample Preparation of 13C-Methyl Isocyanide-Bound Protein

Attach rubber hose from tank of argon to needle/hose adapter and screw long needle onto end of adapter.

Insert NMR tube-sized rubber septum into NMR tube containing protein sample and fold down top edge to secure and seal tube.

Insert long needle attached to end of adapter into NMR tube through septum all the way to bottom of tube. Insert short needle through septum into NMR tube to serve as exhaust valve during subsequent bubbling of argon to remove O2.

Slowly open regulator valve on argon tank to allow just enough pressure to get a steady stream of argon bubbles rising through solution, but not enough pressure to push liquid to top of tube. Allow argon to gently bubble through solution for 15 min to completely remove all oxygen (see Note 4).

Add a pinch of solid sodium dithionite to the NMR tube containing the sample—just enough to cover the end of a lab spatula should be more than enough. Cap the NMR tube and invert several times to ensure complete dissolution and hence reduction of the entire sample.

Add enough 13C-methyl isocyanide to have a slight excess of it relative to the heme protein (13C-methyl isocyanide: heme protein (assuming 1 heme/protein) ratio of about 1.2: 1) (see Note 5). Solution should change color from reddish brown to reddish orange. This spectral change can be observed more precisely with a UV–Vis spectrometer by observing that the Amax redshifts or shifts towards a value of either 430 or 455 nm.

3.3 Collection of NMR Data

Place the sample in the NMR spectrometer.

Lock, tune and match, and shim on the sample, as would be done for any NMR sample.

Find the 90° pulse width, using either the residual water peak or a sample peak.

Set up a normal 2-D lH-13C HSQC experiment, but with the number of increments set to one (“ni” = 1) so that the HSQC becomes a 13C-filtered 1H 1-D experiment.

After checking all the parameters to make sure that they are reasonable, enter the value of the 90° pulse width that was just determined on the sample and ensure that the number of scans (e.g., “ns”) is sufficient for about a 10-min experiment.

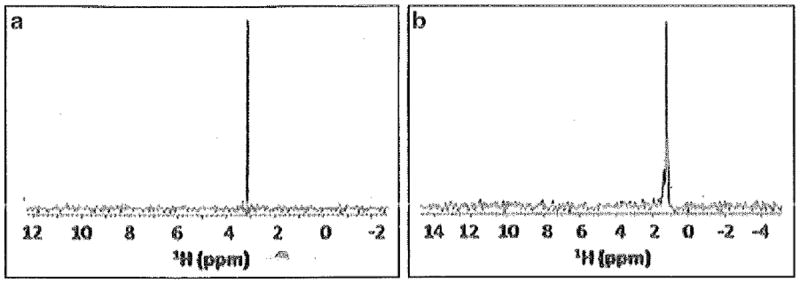

Process the data as usual, with little to no line broadening, and check spectrum. It should be similar to that shown in Fig. 4, with any remaining “free” methyl isocyanide giving a peak at ~3.1 ppm and any additional peaks, probably in slow exchange with the “free” peak, representing “bound” form(s).

Next, take the NMR sample and, after removing the cap, quickly add an aliquot of the ligand solution, whose binding is being screened for.

Run the experiment again, as in steps 4–6, to see what effect the addition of ligand had on the bound 13C-methyl isocyanide peak (see Note 6). One can titrate and monitor chemical-shift change as a function of ligand concentration, fitting data to obtain a dissociation constant (see Note 7).

Once back in the lab, the presence of inactive protein (P420) in the sample can be checked by bubbling CO through the tube, as was done with argon in preparation of the sample, and checking for the presence of an absorbance band at 420 nm, indicating inactive protein.

Fig. 4.

13C-filtered 1H 1-D spectra of 13CH3NC that is (a) unbound or (b) bound to Fe2+-P450cam

Acknowledgments

We thank Professors Rajendra Rathore, Milo Westler, and Bill Donaldson for helpful discussions. This research was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health grants S10RR019012 (D.S.S.), GM085739 (D.S.S.), and GM3553 (L.W.), and also made use of the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison (NIH: P41RR02301, P41GM66326). Remote connectivity was with Abilene/Internet2, funded by NSF (ANI-0333677).

Footnotes

Sodium dithionite is readily hydrated to bisulfate. For longer-term storage, it is best to store in a desiccator.

All cyanide salts are very dangerous, but especially labile cyanide salts such as potassium cyanide. Do not mix with acid, as this would form gaseous HCN, which can be readily inhaled. While handling KCN, a solution of hydroxocobalamin and sodium thiosulfate is kept nearby (antidote) and a colleague must observe the researcher at all times for any accidental toxicity. The hydroxocobalamin and sodium thiosulfate are part of the typical cyanide antidote kits available commercially and their use is approved in the USA. The hydroxocobalamin reacts with cyanide to form a stable and nontoxic cyanocobalamin that is eliminated from the body through urine. As stated above, KCN is highly toxic and releases hydrogen cyanide gas upon reaction with acids. Potassium cyanide solutions and glassware with which these have been in contact must be treated with an excess of potassium permanganate (4–5 g of KMnO4 for 1 g of KCN) and rinsed with plenty of water. After treatment, liquid waste should be disposed of by a certified cyanide waste disposal company (e.g., one which deals with cyanide waste generated from metal plating companies).

The unusual 14N-1H scalar coupling (2J-coupling, producing the triplet) was only apparent in d4-methanol and D2O; in other solvents that were used, including d3-acetonitrile, d1-chloroform, and d6-benzene, and when complexed with protein, the spectrum only showed the large doublet splitting from the 13C-1H coupling. Although this unusual quadrupolar coupling—and implied long quadrupolar relaxation time—stems from the high degree of axial symmetry and short correlation time of this molecule and, as such, is only an interesting side note (i.e., would not be observed when bound to protein), this property has practical importance in that it can help confirm the identity of 13CH3NC, allowing it to be easily distinguished from the most common side product—13C-methyl-labeled acetonitrile.

We find that with this step it pays to be patient, as it is the easiest way to lose your sample—and weeks of hard work—throughout this procedure. We advise that the flow rate of argon is increased very slowly to ensure that the sample is not lost with excess bubbling, popping off of the septum, and spilling, or simply denaturing protein as a result of excessive bubbling.

We find it helpful to have a slight molar excess of 13C-methyl isocyanide so that we can distinguish unambiguously the free form and the bound form, provided they are in slow exchange on the chemical-shift timescale. In addition, this slight excess of free 13C-methyl isocyanide allows us to determine whether, upon addition of substrate or ligand to the mixture, the bound 13C-methyl isocyanide is perturbed or simply displaced, once again yielding free 13C-methyl isocyanide.

The chemical shift of the 13C-methyl isocyanide protons will be affected by the anisotropic environment above the heme group, in addition to the relative population of linear and bent forms of the molecule itself. Both of these factors contribute to the increased shielding or deshielding these protons experience and, hence, whether the bound resonance will be upfield-shifted or downfield-shifted.

If ligand (inhibitor or substrate) binds while 13CH3NC remains bound, one can monitor changes in chemical shift of 13CH3NC due to the presence of simultaneously bound ligand. But if ligand and 13CH3NC sterically exclude each other, titration with ligand will lead to displacement of 13CH3NC, which can also be monitored, due to its distinct chemical shift.

References

- 1.Furge LL, Guengerich FP. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism and chemical toxicology. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2006;34:66–74. doi: 10.1002/bmb.2006.49403402066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams PA, Cosme J, Sridar V, Johnson EF, McRee DE. Mammalian microsomal cytochrome P450 monooxygenase: structural adaptations for membrane binding and functional diversity. Mol Cell. 2000;5:121–131. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams PA, Cosme J, Ward A, Angove HC, Matak Vinkovic D, Jhoti H. Crystal structure of human cytochrome P450 2C9 with bound warfarin. Nature. 2003;424:46–464. doi: 10.1038/nature01862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams PA, Cosme J, Vinkovic DM, Ward A, Angove HC, Day PJ, Vonrhein C, Tickle IJ, Jhoti H. Crystal structure of human cytochrome P450 3A4 bound to metyrapone and progesterone. Science. 2004;305:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1099736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott EE, He YA, Wester MR, White MA, Chin CC, Halpert JR, Johnson EF, Stout CD. An open conformation for mammalian cytochrome P450 2B4 at 1.6 A° resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13196–13201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133986100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomita T, Ogo S, Egawa T, Shimada H, Okamoto N, Imai Y, Watanabe Y, Ishimura Y, Kitigawa T. Elucidation of the differences between the 430- and 455-nm absorbing forms of P450-isocyanide adducts by resonance Raman spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36261–36267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee DS, Park SY, Yamane K, Obayashi E, Hori H, Shiro Y. Structural characterization of n-butyl-isocyanide complexes of cytochromes P450nor and P450cam. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2669–2677. doi: 10.1021/bi002225s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simonneaux G, Bondon A. Isocyanides and phosphines as axial ligands in heme proteins and iron porphyrin models. In: Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. The porphyrin handbook. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 299–311. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pellecchia M, Meininger D, Dong Q, Chang E, Jack R, Sem DS. NMR-based structural characterization of large protein- ligand interactions. J Biomol NMR. 2002;22:165–173. doi: 10.1023/a:1014256707875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Showalter SA, Johnson E, Rance M, Bruschweiler R. Toward quantitative interpretation of methyl side-chain dynamics from NMR and molecular dynamics simulations. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14146–14147. doi: 10.1021/ja075976r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tugarinov V, Kanelis V, Kay LE. Isotope labeling strategies for the study of high-molecular-weight proteins by solution NMR spectroscopy. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:749–754. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavanagh J, Fairbrother WJ, Palmer AG, III, Rance M, Skelton NJ. Protein NMR spectroscopy. 2. Academic; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedman TB, Nixon ER. Matrix isolation studies of methyl cyanide and methyl isocyanide in solid argon. Spectrochim Acta Biochim. 1972;28A:1375–1391. [Google Scholar]