Abstract

A potential ion-exchange material was developed from poly(acrylonitrile) fibers that were prepared by electrospinning followed by alkaline hydrolysis (to convert the nitrile group to the carboxylate functional group). Characterization studies performed on this material using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, Fourier-Transform infra-red spectroscopy, and ion chromatography confirmed the presence of ion-exchange functional group (carboxylate). Optimum hydrolysis conditions resulted in an ion-exchange capacity of 2.39 meq/g. Ion-exchange fibers were used in a packed-bed column to selectively remove heavy-metal cation from the background of a benign, competing cation at a much higher concentration. The material can be efficiently regenerated and used for multiple cycles of exhaustion and regeneration.

Key words: : characterization, electrospinning, hydrolysis, ion-exchange fibers, poly(acrylonitrile)

Introduction

Since the 1940s, when it was used for the first time as a process for separating some of the critical trans-uranium elements in the pursuit of nuclear weapons, ion exchange has found a wide range of applications, including catalysis, drug delivery, sensors, bioseparation, ore beneficiation, metallurgy, food purification, biorenewable energy, water treatment, environmental processes, and nanotechnology. Ion exchange is a reversible chemical reaction where in the most commonly used form a target ion from solution is exchanged with an equivalent amount of another ion of the same charge that is attached to an immobilized solid phase (Sengupta and SenGupta, 2007). The morphology of the immobilized solid phase, termed the ion exchanger, is a sphere with a diameter of 75–1,000 μm, a membrane (100–10,000 μm thick), or a composite sheet (500–2,000 μm thick). These morphologies suffer from a number of physiochemical limitations that restrict their use, including (1) inability to be used in reactors with highly suspended solids/slurries due to filter ripening and pore clogging; (2) mass transfer limitations resulting in slow exhaustion and regeneration kinetics; and (3) minimum size/thickness constraints. In addition, with spherical ion-exchange resins, the most commonly used form of ion exchangers, the material is vulnerable to damage due to pressure exerted while in operation (Chiu et al., 2011). These limitations can be overcome by ion-exchange fibers (IXF) because of their two-dimensional geometry, proximity of the functional group on the surface of the material, and also as there is no cross-linking agent that is subject to stretching at any time.

A number of fiber-based ion-exchange materials have been proposed. Chelating fibers with varying substrates (e.g., polymer fiber or natural fiber etc.) and functional groups (e.g., amino, thio, oxo, carboxyl etc.) have been developed (Shin et al., 2004). IXF can be viewed as slender strands consisting of a polymeric backbone with functional groups covalently attached to the fiber surface. Compared with ion-exchange resins, IXF have a number of distinct advantages, including faster kinetics (due to reduced length of ion transport) and ability to be regenerated with benign reagents due to placement of functional groups on or close to the surface (Greenleaf et al., 2006). IXF can also be used in reactors with highly suspended solids (not possible with IX resins) or be woven into filtration material or fabric. Other advantages include the ability of being easily compressed or loosened in a packed bed according to the operational requirements, and flexibility in usage for the removal of soluble pollutants. IXF also have the unique advantage compared with other ion exchangers due to their ability to be processed into a wide range of diverse forms (Deng and Bai, 2003; Matsumoto et al., 2006).

A number of examples exist pertaining to the development and application of IXF (Soldatov et al., 1988, 1999; Dominguez et al., 2001; Jaskari et al., 2001; Economy et al., 2002; Greenleaf et al., 2006; Greenleaf and SenGupta, 2006). IXF have been created from a number of different polymers and utilized in various applications such as ultrafiltration, water treatment, and superabsorbent fibers (Yang and Tong, 1997; Gupta et al., 2004; Shin et al., 2004; Matsumoto et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2010b). Poly(acrylonitrile) (PAN) is considered one of the most important fiber-forming polymers due to properties such as high strength, abrasion resistance, desirable chemical resistance, thermal stability, low flammability, and low cost. It has been extensively used in the form of membranes and micron-sized fibers for applications such as ultrafiltration (Bryjal et al., 1998; Deng and Bai, 2004; Lohokare et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2009b; Zhang et al., 2009, 2010a), water treatment (Deng and Bai, 2003, 2004; Deng et al., 2008), and superabsorbent fibers (Gupta et al., 2004). Shunkevich et al. (2005); Zhang et al. (2008) reported the use of micron-sized PAN fibers as the basis for development of IXF.

The minimum diameter of IXF mentioned earlier is reported to be around 10 μm, which limits some of the advantages listed earlier. Sub-micron IXF, in theory, could significantly enhance the specific surface area and, therefore, the number of functional groups on the surface. Electrospinning, a simple and cost-effective process, is a mature platform technology; excellent publications discuss its theory and applications (Reneker et al., 2000; Gibson et al., 2001; Shin et al., 2001; Dzenis, 2004; Kaur et al., 2006; Ramakrishna et al., 2006). It has been employed to generate submicron polymeric IXF (Huang et al., 2003; An et al., 2006; Matsumoto et al., 2006; Teo and Ramakrishna, 2006; Wang et al., 2009a; Neghlani et al., 2011) in the 40–2,000 nm range.

Alkaline hydrolysis has been successfully employed as an effective technique to modify the surface properties of PAN. Alkaline hydrolysis primarily hydrolyzes the nitrile group and converts it into carboxylic acid, which enables the material to act as a weak-acid cation exchanger. Yu et al. (2009) and Liu and Hsieh (2006) have demonstrated the use of electrospun PAN fibers in treatment of phenol and heavy metal polluted water and in superabsorbent membranes. However, Yu et al. (2009) used a PAN/kaolinite hybrid material for treating heavy-metal polluted water, the preparation of which is not a simple process. Zhang et al. (2010a) utilized hydrolyzed PAN electrospun fibers as affinity membranes for bromelain adsorption, with bromelain adsorption capacity of 161.6 mg/g. Chiu et al. (2011) have used a carboxylate functional group ion exchanger for lysozyme adsorption, but they used a poly(ethyleneterephthalate) meltblown fabric with upper and lower PAN (a copolymer of acrylonitrile and vinyl acetate) layers and reported the ligand capacity (-COOH density) to be around 439.8 meq/g (∼0.44 meq/g). Their work mainly emphasized the role of pore size and electrospinning time in lysozyme adsorption on a trilayer membrane of thickness in the range of 200 μm and compared it with that of a commercially available membrane of a different base material.

In summary, IXF have the potential to overcome the shortcomings of the beads but have not demonstrated widespread use due to (1) difficulty in synthesizing the material; (2) inability of the material to be used over a number of cycles, a critical need as ion-exchanger materials are too expensive to be applied in a once-use-and dispose scenario; and (3) inability to be used in a continuous reactor application. With regard to removal of trace concentration of heavy metals from contaminated water, if the diameter of the IXF is <100 nm, its ability to be packed in a bed and yet be porous enough to enable passage of contaminated water at a practical velocity (such that the Empty Bed Contact Time [EBCT] is in the order of <10 min) are compromised. On the other hand, if the IXF diameter is >100 μm, packing it in a bed creates such a high porosity that contact of the contaminant heavy-metal ion with the functional group on the surface of the IXF may not be complete, resulting in an unacceptable level of leakage.

In this current study, we fabricated a weak-acid cation-exchange fiber by electrospinning pure PAN (100% homopolymer) followed by subsequent hydrolysis. The most useful advantage of using a 100% homopolymer is the consistency of results obtained, as there is no interference from copolymers/hybrid materials. The focus of our study is to characterize its material and ion-exchange properties, and compare them with those of the micron-sized fiber form of PAN polymer. The latter investigation provides an insight into the role that size (diameter) plays in material properties and application effectiveness. In addition, the effect of time, temperature, and two alkali species, NaOH and KOH, was studied on the hydrolysis of electrospun PAN fibers and its ion-exchange capacity (IEC). Finally, the ability of the hydrolyzed micron-sized PAN fiber to be run in a packed-bed column over repeated cycles to affect heavy metal (Cu) removal is also presented. This also necessitates efficient regeneration of the IXF and its robustness to withstand multiple cycles of exhaustion and regeneration.

Experimental Protocols

Reagents

PAN polymer (Mw 150,000 g/mol) was purchased from Scientific Polymer Products, Inc. Micron-sized staple PAN fibers were supplied by William Barnet & Son, Inc. NaOH (10 N) was purchased from Fisher Scientific, and N,N′-Dimethylformamide (DMF, 99%) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co. A sample of weak-acid cation-exchange resin of carboxylate functional group, Amberlite CG-50, produced by the Dow Chemical Company, was purchased from Fisher Scientific. Its nominal particle size was 75–150 μm, and its IEC was determined to be 3.3 meq/g. De-ionized water was used to dilute the sodium hydroxide solution to a required concentration and for washing the samples. All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co.

Electrospinning

PAN/DMF solution, with a concentration of 10 wt.%, was prepared by stirring at a temperature of 70°C until a homogeneous solution was obtained. The viscosity of this solution was measured to be around 2280 cP. PAN fibers were electrospun at a constant flow rate of 2.4 mL/h, which was maintained using a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus). A voltage of 20 kV was applied between the needle and collector plate using a high-voltage power supply (Gamma High Voltage Research), and the tip to collector distance was maintained at 21.6 cm. The electrospinning process was carried out at 20°C±2°C. Electrospun fibers were collected on an aluminum plate that was placed on an insulated platform. Fiber collection was random and in the form of a nonwoven mat. Electrospinning of PAN has been studied in detail (Liu and Hsieh, 2006; Moroni et al., 2006; Sutasinpromprae et al., 2006; Wang and Kumar, 2006; Zhang et al., 2010a; Chiu et al., 2011) for various applications, including carbon fiber preparation and environmental engineering applications, and the parameters used for electrospinning in the present study were chosen based on a review of existing literature.

Apparatus and instrumentation

Viscosity of the electrospinning solution was measured using a DV II+viscometer from Brookfield that was equipped with a temperature controller TC-102.

A Fourier-Transform infra-red spectrometer (FTIR) - FTS 3000MX, (Digilab) - supplemented with a Bio-Rad UMA 500 Infrared microscope was used to analyze the sample composition before and after hydrolysis.

Surface characteristics of electrospun fibers and micron-sized fibers were analyzed using a JEOL M5610 (Peabody) scanning electron microscope (SEM). The fiber samples were placed on an SEM stub that was covered with double-sided sticky carbon tabs, and they were sputter coated with gold using a Denton Vacuum Desk IV sputtering machine. Fiber diameter was measured using image-processing software (ImageJ; National Institute of Health).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (PHI Quantum 2000; Physical Electronics, Inc.) was used to analyze the surface elemental composition of the material before and after functionalization.

IEC was determined from mass balance in binary isotherm tests. The IXF preloaded with one cation (Na+) was placed in a solution with a known concentration of another counterion (e.g., Ca2+). After 24 h of stirring, while the pH was maintained between 8 and 9, equilibrium was assumed to be attained. The mass of one counterion lost from the solution (Ca2+) and the other (Na+) released into the solution from the IXF was obtained from ion chromatography analysis (Dionex ICS-90) of the initial and final solution. The ICS-90 was run with 20 mM methanesulfonic acid as the eluent, 100 mM tetrabutylammonium hydroxide as the cation regenerant, and a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. These data were used to determine the IEC, hereafter reported as milliequivalents per dry gram (meq/g) of the material (Helfferich, 1995). Significance testing was done using Analysis-of-Variance (ANOVA) test, and the significance was set at a p-value that was less than or equal to 0.05.

An atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 300, flame mode) was used to determine the copper concentration of various initial and final solutions for selectivity factor and kinetic uptake experiments.

Hydrolysis

Two forms of PAN, micron-sized fibers and electrospun fibers, were treated chemically with an alkali to obtain an ion-exchange material by converting the nitrile groups present in the native PAN to carboxylic acid groups. The material was hydrolyzed based on the conditions reported by Zhang et al. (2009). Briefly, about 1 g of PAN was added to 250 mL solution of 2 N NaOH or 2 N KOH prepared in deionized water at different time and temperature conditions under stirring. After treatment, the material was allowed to cool and then washed extensively with de-ionized water. The functionalized PAN was dried in an oven at 40°C and placed in an appropriate solution for determination of IEC. The experiments were replicated identically at least thrice for IEC determination.

Separation factor coefficient determination

Hydrolyzed electrospun fibers preloaded with copper were regenerated using 0.01 M nitric acid. Next, they were loaded with Ca2+ by stirring them in a calcium nitrate solution (10,000 mg/L as Ca+2). The pH was maintained >8 by addition of calcium hydroxide solution over the period of 24 h. After the specified time interval, fibers were again filtered, thoroughly rinsed with DI water, and loaded with different concentrations of copper nitrate solution (30–150 mg/L as Cu+2). No pH adjustment was made over the time interval of the process and after 24 h, the fibers were filtered and stored in DI water until further use. The solutions were analyzed for Cu and Ca concentrations. The experiments were replicated identically thrice for selectivity factor determination.

Uptake kinetics

After hydrolysis, a predetermined mass of fibers (prepared in the lab according to the procedure outlined in Electrospinning section) or resin of the same functional group (carboxylate - commercial name Amberlite CG-50 available from the Dow Chemical Company, no commercial endorsement implied) was inserted in a rapidly stirred 0.1 M NaCl solution for 24 h to achieve saturation Na+ loading. pH >8.0 was maintained through use of 0.1 N NaOH. Next, the fibers or resin beads were filtered, thoroughly rinsed with DI water, and loaded with calcium nitrate solution (133.33 mg/L as Ca+2) for 24 h under stirring with the pH maintained at >8 through use of calcium hydroxide solution. After 24 h, fibers or resin beads were filtered and loaded with copper nitrate solution for kinetic uptake determination (initial Cu+2 conc.=100 mg/L). pH was not adjusted, and a predetermined volume of the solution was withdrawn at each time point (30 s–24 h) for copper analysis. Calcium concentration of the samples was carried out to establish equivalent exchange.

Column experiment

Fixed-bed column runs were carried out in Adjusta Chrom® (Ace Glass, Inc.) glass columns that were 300 mm long with a 25 mm inner diameter. A predetermined mass of micron-sized, hydrolyzed PAN fibers was packed into the column. The influent was pumped into the column in a downflow direction using synchronous pumps, FMI Lab Pump, Model QSY (Fluid Metering, Inc.). Effluent sample from the column was collected by a Spectra/Chrom® CF-1 Fraction Collector (Spectrum Chromatography). The flow was adjusted to maintain constant EBCT for all the column runs at 3.5 min. An online pH meter was also connected in the system to monitor the effluent pH. Regeneration of the bed was performed similarly by passing the regenerant (0.01 M nitric acid) in a downflow direction, and the spent regenerant samples were also collected in a similar fashion. The regenerated bed was rinsed with deionized water, after which a 10,000 mg/L (as Ca2+) calcium nitrate solution was passed for 10 BV to be preloaded with Ca2+ and to be used for another exhaustion run.

Results and Discussion

Fiber characterization

Figure 1 depicts the SEM images of the electrospun PAN fibers and micron-sized staple PAN fibers. The corresponding diameter distribution for both types of fibers is shown in Fig. 2. For the electrospun fibers, before functionalization, the SEM image reveals a uniform and nonbeaded fiber morphology. The average fiber diameter is ca. 720 nm and the diameter distribution shows a small tail, which is characteristic of the size distribution for electrospun fibers (Chen et al., 2006). Diameter analysis of the micron-sized staple fibers revealed an average fiber diameter of 19.66 μm, with a much smaller variability in the fiber size distribution. This behavior is attributed to the difference in the spinning technique that is utilized to form the two fibers. During fiber formation by electrospinning, the initial stages of whipping instability result in a massive jet thinning, resulting in uneven fiber stretching (Fang et al., 2010). This phenomenon is absent in the solution spinning process that was used to generate micron-sized staple fibers.

FIG. 1.

SEM image of (a) Electrospun poly(acrylonitrile) (PAN) fibers (b) Micron-sized staple PAN fibers (Magnification: 500, Scale bar: 50 μm).

FIG. 2.

(a) Diameter distribution of electrospun PAN fibers, average fiber diameter 720 nm, (b) Diameter distribution of micron-sized staple PAN fibers, average fiber diameter 19.66 μm.

Hydrolysis chemistry

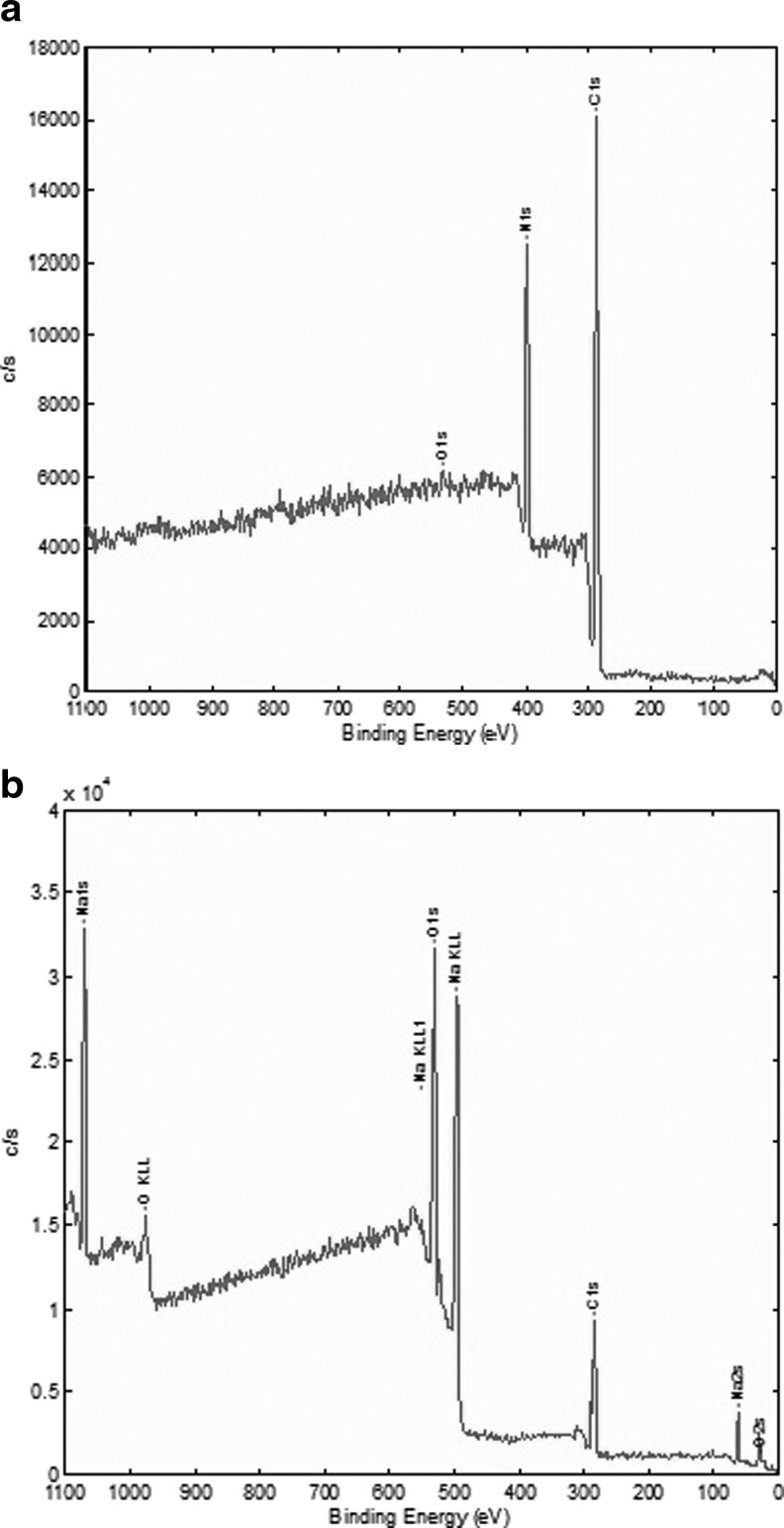

Table 1 shows the XPS data of atomic weight% of elements in electrospun PAN before and after hydrolysis with 2 N NaOH. The results depict an increase in the oxygen to carbon ratio from 0.017 to 0.829 and a decrease in the nitrogen to carbon ratio from 0.297 to 0.018. The nitrile group of PAN can be hydrolyzed to amide and carboxylic groups by reacting it with an alkali (Yang and Tong, 1997; Bajaj and Kumari, 1988). Litmanovich and Platé (2000) hypothesized that, initially, hydrolysis results in≈20% amidines which are situated in the nearest neighborhood of carboxylate groups, and after complete hydrolysis of the amidines, poly[(sodium acrylate)-co-acrylamide] is formed. However, we did not find any evidence of this reaction scheme. The almost complete absence of nitrogen in the hydrolyzed sample obviously indicates the absence of any amide. Figure 3 shows the XPS survey and elemental scan of alkali hydrolyzed electrospun PAN, where the binding energy values are reported for carbon 1s (285 eV), oxygen 1s (533 eV), nitrogen 1s (around 400 eV), and sodium 1s (1072 eV). It is obvious that the nitrile bonds present in unfunctionalized PAN have been converted into carboxylic acid groups, with the hydrogen being replaced with sodium ions as the carboxylic functionality would remain mostly in the form of–COO−Na+ (Zhang et al., 2010b). It has been reported that PAN with a certain content of–COOH swells easily when it is exposed to an aqueous medium (Wang et al., 2007). The same phenomenon was observed after the hydrolysis reaction in the present experiments, further indicating the presence of carboxylic acid groups.

Table 1.

XPS Analysis of Electrospun PAN Fibers Before (PAN) and After Hydrolysis (HPAN) with Sodium Hydroxide (Treated with 2 N NaOH at 70°C)

| Atomic% | PAN | HPAN |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon | 76.2 | 39.7 |

| Oxygen | 1.3 | 32.9 |

| Nitrogen | 22.6 | 0.7 |

| Sodium | 26.7 | |

| O/C ratio | 0.017 | 0.829 |

| N/C ratio | 0.297 | 0.018 |

PAN, poly(acrylonitrile); XPS, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.

FIG. 3.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy analysis of electrospun PAN fibers before (a) and after (b) hydrolysis with sodium hydroxide.

Figure 4 shows the FTIR scan for various electrospun PAN fibers before and after hydrolysis with NaOH and KOH. Here, control refers to electrospun fibers treated with water under same conditions to rule out any effect of water on the fibers at high temperature (70°C). The electrospun PAN fibers and the control PAN fibers show a characteristic peak around 2,242 cm−1 that corresponds to the–CN bond. The hydrolysis, with both NaOH and KOH, leads to the development of peaks around 1,700 cm−1, which is attributed to the C=O bond stretching for the carboxylic acid group and a broad peak around 3,300 cm−1, that corresponds to the–OH bond stretching present in the carboxylic acid (Oh et al., 2001a, 2001b; Lohokare et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2010b). It is evident from these results that the nitrile bonds present in PAN polymer are being hydrolyzed to carboxylic acid groups, which can be utilized for ion-exchange applications.

FIG. 4.

FTIR spectra for electrospun PAN fibers before and after hydrolysis with sodium hydroxide and potassium hydroxide (1: -OH group, 2: -CN group, 3: -C=O group, ESPAN: Electrospun PAN, AHESPAN: Alkali Hydrolyzed Electrospun PAN).

Optimization of hydrolysis conditions

Based on experiments performed at different time and temperature conditions (data not shown), hydrolysis process conditions were optimized at 70°C and 30 min to obtain maximum IEC for electrospun fibers. Table 2 shows the IEC after hydrolysis with either NaOH or KOH for electrospun as well as for micron-sized fibers. Control samples were prepared by treating electrospun fibers with de-ionized water (under the same reaction conditions utilized for functionalization by alkali hydrolysis) to determine whether it resulted in the formation of hydrolyzed functional groups. Negligible IEC was found in the control samples, indicating that alkali treatment alone hydrolyzes nitrile groups of the PAN polymer and, therefore, is responsible for formation of the carboxylate functional groups. Further, the results indicate that the electrospun fibers show higher IEC as compared with the micron-sized fibers. Statistical significance analysis shows that the results obtained for the electrospun fibers are significantly different from the micron-sized fibers (p<0.05). This could be due to the higher surface area obtained by using sub-micron-sized fibers, which present more nitrile groups on the surface for hydrolysis. Our results are consistent with the work done by Neghlani et al. (2011), where a comparison of metal adsorption capacity of aminated PAN nanofibers and microfibers revealed the functionalization percentage to be 30% and 6%, respectively. They attributed this effect to the higher specific surface area provided by smaller-diameter nanofibers and a large number of chelating amine sites present on the aminated nanofibers.

Table 2.

Effect of Different Alkali Species and Material Form of PAN Polymer on Ion-Exchange Capacity

| Experiment set | Material | Reagent | Time (min) | Ion-exchange capacity (meq/dry gm) (Mean±SD) | Number of repeats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ES fibers | Water | 30 min | 0.03±0.04 | 3 |

| Hydrolyzed | ES fibers | 2 N NaOH | 30 min | 1.96±0.89 | 4 |

| Hydrolyzed | ES fibers | 2 N KOH | 30 min | 2.39±0.87 | 4 |

| Hydrolyzed | Micron-sized Fibers | 2 N NaOH | 30 min | 0.36±0.06 | 3 |

ES, Electrospun fibers (Average diameter: 720 nm), Micron-sized fibers (Average diameter: 20 μm). All experiments were conducted at 70°C.

From Table 2, it is evident that the treatment with KOH gives higher values as compared with treatment with NaOH. Zhang et al. (2009) observed the difference in functionalization of PAN membranes due to the two different alkali species and attributed the difference (in the degree of hydrolysis) to the attack strength of the hydroxyl group. Young (2002) posited this to the tendency to form ion pairs; that is, the tendency to form ion pairs is greatest in LiOH followed by NaOH, although experimental evidence was missing to support ion pair formation in KOH. In the present work, although the results are not significantly different, they are in agreement with the results reported by Zhang et al. (2009).

Although alkali hydrolysis resulted in a significant increase in IEC, the functionalization reaction resulted in degeneration of the fiber morphology. A similar hydrolysis protocol was followed by Chiu et al. (2011) but they did not report any degeneration of fiber morphology. This could be due to their use of PAN polymer that is basically a copolymer of acrylonitrile and vinyl acetate, instead of pure PAN (100% homopolymer) used in the present study. However, their reported ligand capacity (∼0.44 meq/g) was significantly less than that obtained in the present study (∼1.96 meq/g). Preserving the morphology of the electrospun nanofibers immediately after hydrolysis created a challenging situation. After hydrolysis, the fibers turned into a gel-like state and if subsequently dried, would turn into a hardened mass. Figure 5a shows the SEM image taken after drying the hydrolyzed fibers. However, it was observed that after immersing the fibers into different aqueous solutions for measuring IEC, the fibers regained their morphology as depicted in Fig. 5b. Yang and Tong (1997) observed that at high pH, the poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) layer present on the hydrolyzed fibers swell and turn into a hydrogel. During hydrolysis, the electrospun fibers are subjected to a very high pH (∼13) in the 2 N NaOH or KOH solution. This may give rise to the hydrogel layer of PAA in the present case. However, during the subsequent processes, the pH of various rinsing and loading solutions is near neutral and this might reduce/eliminate the hydrogel formation, leading to the reappearance of the fiber morphology.

FIG. 5.

SEM images of electrospun fibers after (a) hydrolysis (b) calcium loading for capacity determination (Magnification: 2500, Scale bar: 10 μm).

In order to have a better control over the fiber morphology, trials were done with alternative process conditions and the results are listed in Table 3. The results show that if the time of hydrolysis is reduced from 30 min to 15 min or mechanical agitation is not applied during hydrolysis, the fiber morphology is better preserved. Conversely, if the fibers are immersed in the hydrolyzing solution for a long time, the IEC increases, but the fibers are again converted into a gel-like state.

Table 3.

Fiber Morphology of Hydrolyzed Electrospun PAN Fibers Under Various Conditions (Treated with 2 N NaOH at 70°C)

| Variable | Time (min) | Condition | Fiber morphology | SEM images |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical agitation, time | 15 min | No stirring | Improved morphology |  |

| Time | 15 min | Stirring | Improved morphology |  |

| Mechanical agitation | 30 min | No stirring | Improved morphology |  |

| Mechanical agitation | 30 min | Stirring | Gel kind |  |

| Mechanical agitation, time | 4 h | No stirring | Gel kind |  |

Separation factor

Chelating exchangers are coordinating polymers with covalently bound side chains which contain one or multiple donor atoms (Lewis bases) that can form coordinate bonds with most of the toxic metal ions (Lewis acids). Due to coordination-type interactions, chelating exchangers offer extremely high selectivity toward commonly encountered toxic Me(II) cations, namely, Cu2+, Pb2+, Ni2+, Cd 2+, and Zn2+, over competing alkaline (Na+, K+) and alkaline-earth

(Ca2+, Mg2+) metal cations.

In the case of Cu2+ - Ca2+ exchange described in Separation factor coefficient determination section, the ion-exchange reaction may be written as

|

A modified form of the equilibrium relationship for this reaction is given by the Separation Factor, which is a dimensionless measure of relative selectivity between two competing ions, and, in this case, equal to the ratio of distribution coefficient of Cu(II) concentration between the exchanger phase and the aqueous phase to that of calcium ion and is given as follows:

|

For this reaction, the Coulombic and hydrophobic interactions play an insignificant role as both the ions are divalent. However, Lewis acid-base interaction plays a critical role as the binding constant for Cu with the closest ligand analog in the aqueous phase (acetate) is almost 10 times higher than that with Ca - log CaL binding constant=1.2, while log CuL binding constant=2.2 and CuL2=2.6 (Morel and Herring, 1993). Figure 6 shows the profile of αCu/Ca for the hydrolyzed electrospun fiber. The results match data obtained by Roy (1989) and SenGupta et al. (1991) for carboxylate resin. Sengupta et al. (2002) have demonstrated a linear relationship between experimentally determined metal/calcium separation factor for a commercial carboxylate resin (DP-1, no commercial endorsement implied) and aqueous-phase metal-acetate stability constant values. Data available in Fig. 6 also agree with theoretical explanations of the reduction of heavy metal separation factor value with an increase in the aqueous-phase heavy metal concentration (Hudson, 1986; Warshawsky, 1988; and Helfferich, 1995). Thus, it can be stated that equilibrium properties of the carboxylate electrospun fiber are no different from the carboxylate ion-exchange resin.

FIG. 6.

Plot of selectivity factor of copper over calcium for hydrolyzed electrospun PAN fibers.

Uptake kinetics

Figure 7a shows the profile of fractional uptake of Cu by IXF and commercially available resin beads of the same functional group (carboxylate) versus time of contact. Fractional uptake, F(t)=Mt/M∞, is the ratio of mass of Cu transferred into the exchanger from the aqueous phase at a particular time to the equilibrium mass uptake that was experimentally confirmed to be achieved after 24 h of contact. A detailed discussion of the kinetic model of ion uptake is outside the central objective of this article. In IXF, particle diffusion is usually considered the rate-limiting step (as opposed to liquid film diffusion or chemical reaction) (Stevens and Davis, 1981; Helfferich, 1995; Vuorio et al., 2003). For a two-dimensional analysis of the fiber (Fig. 7b), the governing equation to model the ion-exchange kinetics can be written as follows (Chen et al., 1996):

|

FIG. 7.

(a) Comparison of kinetic uptake of copper for hydrolyzed IXF and ion-exchange beads with carboxylate functionality (Mt/M∞ represents the uptake of copper at a specified time as compared with equilibrium copper uptake at 24 h). (b) Fiber schematic for ion-exchange kinetics model.

where  =diffusivity of fiber,

=diffusivity of fiber,  =ion concentration in the fiber as a function of space and time,

=ion concentration in the fiber as a function of space and time,

R0-r0=depth of penetration of counter ion from the bulk solution, and L=length of the fiber.

Initial and boundary conditions for the equation just cited are

1. At t=0,

(r,0)=0

(r,0)=02. At r=r0,

3. At r=R0,

,

,

where kf=mass transfer coefficient of the film at the interphase of solid–liquid boundary, c(t)=bulk ion concentration,  (R0,t)=ion concentration at r=R0 at the surface of the fiber, and K=partition coefficient.

(R0,t)=ion concentration at r=R0 at the surface of the fiber, and K=partition coefficient.

From this model, it is obvious that the rate of uptake is inversely proportional to the diameter of the fiber. It is easily noticeable from Fig. 7a that at contact time<10 min, the range which is most likely to be the case for a real packed-bed operation, the ion-exchange fibers show a much faster rate of uptake than ion-exchange resin beads. This can be easily attributed to the difference in their size: IXF have an average diameter of 20 μm, while the resin beads have a nominal diameter range of 75–150 μm.

Column experiment

The most common application for any chelating ion exchanger is in the packed-bed mode. Figure 8 shows the effluent profile for a micron-sized fiber packed bed that was fed an influent solution containing a benign ion (Ca2+) which is approximatelyfour times the concentration of a target heavy metal ion (Cu2+). The effluent Cu concentration was below detection limit (100 μg/L) or <0.5 mg/L (10% of the influent concentration) for 80 bed volumes. Although a practical packed-bed application will have more complex influent characteristics, this simple experiment proves that (1) the ion-exchange fibers can be packed in a column with sufficient porosity to enable smooth passage of water at EBCT comparable to that used in ion-exchange resin columns, and (2) the chelating ion-exchange fiber can selectively remove a heavy metal cation from the background of a benign, competing cation.

FIG. 8.

Effluent profile of Cu and Ca for packed-bed fiber column.

Any chelating exchanger synthesized, regardless of its morphology, should be regenerable so that it can be used for multiple cycles. Figure 9 shows the Cu elution profile using 0.01 M HNO3 as the regenerant with an EBCT of 3.5 min (same as for exhaustion run). Evidence of efficient regeneration is obvious from this graph. Mass balance calculations proved that >95% of Cu in the bed was eluted in 8 bed volumes. After regeneration with 0.01 M HNO3 solution, a 10,000 mg/L (as Ca2+) calcium nitrate solution was passed for 10 BV to be preloaded with Ca2+ and then used for another exhaustion run. The two-step process, while appearing more complicated, is, nevertheless, highly efficient. A weak-acid functional group (carboxylate in this case) has the maximum affinity for H+ and, thus, is efficiently regenerated with mineral acid (0.01 M HNO3 in our case). The subsequent step of replacing H+ on the resin with Ca2+ is also efficient, because this exchange is accompanied by neutralization of H+ (with a low concentration of OH− present with the Ca2+). The 2-step process was necessary in this case, because the synthetic copper solution was unbuffered. Three cycles of the chelating ion-exchange fiber in the packed-bed column have been run with each cycle consisting of exhaustion and regeneration, without any deterioration in column performance. Although any practical application will require tens of cycles, preliminary evidence presented here shows promise of applicability of this material for a heavy-metal decontamination scenario.

FIG. 9.

Regeneration profile for packed-bed column.

Conclusions

Sub-micron-sized PAN fibers were prepared by the simple technique of electrospinning and were subsequently functionalized via alkali hydrolyzation to yield weak acid IXF. Optimum hydrolysis conditions were obtained by stirring for 30 min at 70°C in a 2.0 N NaOH, resulting in a maximum IEC of 1.96±0.89 meq/g. IEC was primarily attributed to conversion of nitrile groups to carboxylic acid groups on the PAN fibers; this was supported by XPS and FTIR spectra. Treatment with 2 N KOH, however, gave a higher IEC value (2.39±0.87 meq/g), although these values were not statistically different from those obtained using a 2 N NaOH treatment. The IEC comparison between submicron- and micron-sized fibers of PAN polymer showed higher values for the electrospun, submicron fibers for similar hydrolysis conditions. This work demonstrated the advantages associated with the hydrolyzed sub-micron-sized PAN fibers prepared through electrospinning, for use as an effective ion-exchange material. The principles outlined here can be utilized to generate submicron IXF with a choice of diameter in the range of 200–900 nm. IXF was used in a fixed-bed reactor configuration to affect environmental separation (e.g., of heavy metal cations from a background of benign cations with a much higher concentration), and the material could be reused over multiple cycles in a fixed-bed operation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support by the National Science Foundation Partnerships for Innovation Program through award # IIP-0605163. They are grateful to Earl Ada for assistance with XPS analysis, and to Chen-Lu Yang for providing support for SEM analysis.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- An H., Shin C., and Chase G.G. (2006). Ion exchanger using electrospun polystyrene nanofibers. J. Membr. Sci. 283, 84 [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj P., and Kumari M.S. (1988). Structural investigations on hydrolyzed acrylonitrile terpolymers. Eur. Polym. J. 24, 275 [Google Scholar]

- Bryjal M., Hodge H., and Dach B. (1998). Modification of porous polyacrylonitrile membrane. Angew. Makromol. Chem. 260, 25 [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Patra P.K., Warner S.B., and Bhowmick S. (2006). Optimization of electrospinning process parameters for tissue engineering scaffolds. Biophys. Rev. Lett. 1, 153 [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Yang G., and Zhang J. (1996). A study on the exchange kinetics of ion-exchange fiber. React. Funct. Polym. 29, 139 [Google Scholar]

- Chiu H.T., Lin J.M., Cheng T.H., and Chou S.Y. (2011). Fabrication of electrospun polyacrylonitrile ion-exchange membranes for application in lysozym. Express Polym. Lett 5, 308 [Google Scholar]

- Deng S., and Bai R.B. (2003). Aminated poly(acrylonitrile) fibers for humic acid adsorption: Behaviors and mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol 37, 5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S., and Bai R.B. (2004). Adsorption and desorption of humic acid on aminated polyacrylonitrile fibers. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 280, 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S., Yu G., Xie S., Yu Q., Huang J., Kuwaki Y., and Iseki M. (2008). Enhanced adsorption of arsenate on the aminated fibers: Sorption behavior and uptake mechanism. Langmuir 24, 10961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez L., Benak K.R., and Economy J. (2001). Design of high efficiency polymeric cation exchange fibers. Polym. Adv. Technol. 12, 197 [Google Scholar]

- Dzenis Y. (2004). Spinning continuous fibers for nanotechnology. Science 304, 1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economy J., Dominguez L., and Mangun C.L. (2002). Polymeric ion-exchange fibers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 41, 6436 [Google Scholar]

- Fang J., Wang H., Niu H., Lin T., and Wang X. (2010). Evolution of fiber morphologies during poly(acrylonitrile) electrospinning. Macromol. Symp. 287, 155 [Google Scholar]

- Gibson P.W., Schreuder-Gibson H.L., and Rivin D. (2001). Transport properties of porous membranes based on electrospun nanofibers. Colloid Surface A 187, 469 [Google Scholar]

- Greenleaf J.E., Lin J., and SenGupta A.K. (2006). Two novel applications of ion exchange fibers: Arsenic removal and chemical-free softening of hard water. Environ. Prog. 25, 300 [Google Scholar]

- Greenleaf J.E., and SenGupta A.K. (2006). Environmentally benign hardness removal using ion exchange fibers and snowmelt. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M.L., Gupta B., Oppermann W., and Hardtmann G. (2004). Surface modification of poly(acrylonitrile) staple fibers via alkaline hydrolysis for superabsorbent applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci 91, 3127 [Google Scholar]

- Helfferich F. (1995). Ion Exchange. New York: Dover Publications, Inc [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Zhang Y., Kotaki M., and Ramakrishna S. (2003). A review on polymer nanofibers by electrospinning and their applications in nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 63, 2223 [Google Scholar]

- Hudson M. (1986). Coordination chemistry of selective ion-ex-change resins. In Rodrigues A.E., Ed., Ion Exchange: Science and Technology; NATO ASI Series; Boston, MA: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, pp. 35–66 [Google Scholar]

- Jaskari T., Vuorio M., and Kontturi K. (2001). Ion-exchange fibers and drug delivery: An equilibrium study. J. Control. Release 70, 219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S., Kotaki M., Ma Z., Gopal R., Ramakrishna S., and Ng S.C. (2006). Oligosaccharide functionalized nanofibrous membrane. Int. J. Nanosci 5, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Litmanovich A.D., and Plate N.A. (2000). Alkaline hydrolysis of polyacrylonitrile. On the reaction mechanism. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 201, 2176 [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., and Hsieh Y. (2006). Preparation of water-absorbing polyacrylonitrile nanofibrous membrane. Macromol. Rapid. Commun. 27, 142 [Google Scholar]

- Lohokare H.R., Kumbharkar S.C., Bhole Y.S., and Kharul U.K. (2006). Surface modification of polyacrylonitrile based ultrafiltration membrane. J. Appl. Polym. Sci 101, 4378 [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H., Wakamatsu Y., Minagawa M., and Tanioka A. (2006). Preparation of ion-exchange fiber fabrics by electrospray deposition. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 293, 143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel F.M.M., and Hering J.G. (1993). Principles and Applications of Aquatic Chemistry. New York: Wiley-Interscience, p. 374 [Google Scholar]

- Moroni L., Licht R., de Boer J., de Wijn J.R., and van Blitterswijk C.A. (2006). Fiber diameter and texture of electrospun PEOT/PBT scaffolds influence human mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and morphology, and the release of incorporated compounds. Biomaterials 27, 4911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neghlani P.K., Rafizadeh M., and Taromi F.A. (2011). Preparation of aminated-polyacrylonitrile nanofiber membranes for the adsorption of metal ions: Comparison with microfibers. J. Hazard. Mater. 186, 182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh N., Jegal J., and Lee K. (2001a). Preparation and characterization of nanofiltration composite membranes using poly(acrylonitrile) (PAN). I. preparation and modification of PAN supports. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 80, 1854 [Google Scholar]

- Oh N., Jegal J., and Lee K. (2001b). Preparation and characterization of nanofiltration composite membranes using poly(acrylonitrile) (PAN). II. preparation and characterization of polyamide composite membranes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 80, 2729 [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishna S., Fujihara K., Teo W.E., Yong T., Ma Z., and Ramaseshan R. (2006). Electrospun nanofibers: Solving global issues. Mater. Today 9, 40 [Google Scholar]

- Reneker D.H., Yarin A.L., Fong H., and Koombhongse S. (2000). Bending instability of electrically charged liquid jets of polymer solutions in electrospinning. J. Appl. Phys. 87, 4531 [Google Scholar]

- Roy T.K.M.S. (1989). Thesis, Chelating Polymers: Their Properties and Applications In Relation To Removal, Recovery and Separation of Toxic Metal Ions. Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh University [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S., and SenGupta A.K. (2007). Ion exchange. In Lee S., Ed., Encyclopedia of Chemical Processing. New York: Taylor & Francis, p. 1411 [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S., SenGupta A.K., and Sposito G. (2002). Trace heavy metal separation by chelating ion exchangers. In SenGupta A.K., Ed., Environmental Separation of Heavy Metals: Engineering Processes. Florida: CRC Press, p. 45 [Google Scholar]

- SenGupta A.K., Zhu Y., and Hauze D. (1991). Metal(I I) ion binding onto chelating exchangers with nitrogen donor atoms: Some new observations and related implications. Environ. Sci. Techno. 25, 481 [Google Scholar]

- Shin Y.M., Hohman M.M., Brenner M.P., and Rutledge G.C. (2001). Experimental characterization of electrospinning: The electrically forced jet and instabilities. Polymer 42, 9955 [Google Scholar]

- Shin D.H., Ko Y.G., Choi U.S., and Kim W.N. (2004). Design of high efficiency chelate fibers with an amine group to remove heavy metal ions and pH-related FT-IR analysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 43, 2060 [Google Scholar]

- Shunkevich A.A., Akulich Z.I., Mediak G.V., and Soldatov V.S. (2005). Acid-base properties of ion exchangers. III. Anion exchangers on the basis of polyacrylonitrile fiber. React. Funct. Polym. 63, 27 [Google Scholar]

- Soldatov V.S., Shunkevich I.S., Johann J., and Iraushek H. (1999). Chemically active textile materials as efficient means for water purification. Desalination 124, 181 [Google Scholar]

- Soldatov V.S., Shumkevich A.A., and Sergeev G.I. (1988). Synthesis, structure and properties of new fibrous exchangers. Reactive Polym. Ion Exchangers Sorbents 7, 159 [Google Scholar]

- Stevens T.S., and Davis J.C. (1981). Hollow fiber ion-exchange suppressor for ion-chromatography. Anal. Chem. 53, 1488 [Google Scholar]

- Sutasinpromprae J., Jitjaicham S., Nithitanakul M., Meechaisue C., and Supaphol P. (2006). Preparation and characterization of ultrafine electrospun polyacrylonitrile fibers and their subsequent pyrolysis to carbon fibers. Polym. Int. 55, 825 [Google Scholar]

- Teo W.E., and Ramakrishna S. (2006). A review on electrospinning design and nanofiber assemblies. Nanotechnology 17, R89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuorio M., Manzanares J.A., Murtomaki L., Hiroven J., Kankkunen T., and Kontturi K. (2003). Ion-exchange fibers and drugs: A transient study. J Control. Release. 91, 439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.S., Fu G.D., and Li X.S. (2009a). Functional polymeric nanofibers from electrospinning. Recent Pat. Nanotechnol. 3, 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., and Kumar S. (2006). Electrospinning of polyacrylonitrile nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 102, 1023 [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Yue Z., and Economy J. (2009b). Solvent resistant hydrolyzed polyacrylonitrile membranes. Sep. Sci. Technol. 44, 2827 [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Wan L., and Xu Z. (2007). Surface engineering of polyacrylonitrile-based asymmetric membranes towards biomedical applications: An overview. J. Membr. Sci. 304, 8 [Google Scholar]

- Warshawsky A. (1988). Modern research in ion exchange. In Rodrigues A.E., Ed., Jon Exchange: Science and Technology; NATO ASI Series; Boston, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 43, 1115 [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., and Tong J. (1997). Loose ultrafiltration of proteins using hydrolyzed polyacrylonitrile hollow fiber. J. Membr. Sci. 132, 63 [Google Scholar]

- Young R.A. (2002). Cross-linked cellulose and cellulose derivatives. In Chatterjee P.K. and Gupta B.S., Eds., Absorbent Technology. Netherlands: Elsevier Science B.V., p. 233 [Google Scholar]

- Yu D.-G., Zhang X.-F., Shen X.-X., Zhu , Branford-White C., Yang Y.C., and Welbeck E.D. (2009). Polyacrylonitrile/Kaolinite Hybrid Nanofiber Mats Aimed for Treatment of Polluted Water. Presented at 3rd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, Beijing, China, June11–13 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Chen S., Zhang Q., Li P., and Yuan C. (2008). Preparation and characterization of an ion exchanger based on semi-carbonized polyacrylonitrile fiber. React. Funct. Polym. 68, 891 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Meng H., and Ji S. (2009). Hydrolysis differences of polyacrylonitrile support membrane and its influences on polyacrylonitrile-based membrane performance. Desalination 242, 313 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Nie H., Yu D., Wu C., Zhang Y., Branford-White C.J., and Zhu L. (2010a). Surface modification of electrospun polyacrylonitrile nanofiber towards developing an affinity membrane for bromelain adsorption. Desalination 256, 141 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Song X., Li J., Ji S., and Liu Z. (2010b). Single-side hydrolysis of hollow fiber polyacrylonitrile membrane by an interfacial hydrolysis of a solvent-impregnated membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 350, 211 [Google Scholar]