Abstract

Objective:

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has become an important imaging modality for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. However, no official data exists regarding clinical EUS practice in Latin America (LA). This study assessed current EUS practice and training.

Patients and Methods:

A direct mail survey questionnaire was sent to 268 Capítulo Latino Americano de Ultrasonido Endoscópico members between August 2012 and January 2013. The questionnaire was sent out in English, Spanish and Portuguese languages and was available through the following site: http://www.cleus-encuesta.com. Responses were requested only from physicians who perform EUS.

Results:

A total of 70 LA physicians answered the questionnaire until January 2013. Most of the participants were under 42 years of age (53%) and 80% were men. Most participants (45.7%) perform EUS in Brazil, 53% work in a private hospital. The majority (70%) also perform endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. A total 42% had performed EUS for 2 years or less and 22.7% for 11 years or more. Only 10% performed more than 5000 EUS. The most common indication was an evaluation of pancreatic-biliary-ampullary lesions. Regarding training, 48.6% had more than 6 months of dedicated hands-on EUS and 37% think that at least 6 months of formal training is necessary to acquire competence. Furthermore, 64% think that more than 50 procedures for pancreatic-biliary lesions are necessary.

Conclusion:

This survey provides insight into the status of EUS in LA. EUS is performed mostly by young endoscopists in LA. Diagnostic upper EUS is the most common EUS procedure. Most endosonographers believe that formal training is necessary to acquire competence.

Keywords: survey, endoscopic ultrasound, echoendoscopy, Latin America

INTRODUCTION

In the 80s, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was introduced as a new endoscopic modality, enabling diagnosis, staging and treatment, in selected cases of gastrointestinal, pancreatic-biliary, anorectal and mediastinal diseases. Although, EUS is already available in many countries, there is no official data regarding clinical practice in Latin America (LA). The main objective of this study was to evaluate the current practice of EUS in LA and methods of existing training. Other objectives were to obtain information about cost, fee and reimbursement in EUS procedures.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A web survey form containing four pages with 34 questions (Appendix) was developed in three languages (English, Spanish and Portuguese). Questions 1-27 were obligatory to the completion of the questionnaire and were related to clinical practice and training. Questions 28-34 were optional and related to costs, fees and reimbursement for EUS.

A message containing a link to the online questionnaire was sent directly via E-mail, in August 2012, to 268 Capítulo Latino Americano de Ultrasonido Endoscópico (CLEUS’) members — organization, which represents physicians interested in EUS in LA). The message was also forwarded to other physicians who perform EUS (non-CLEUS’ members) through E-mail by the CLEUS’ members who had received the link. The questionnaire was developed together with an IT company (Trajettoria Information Technology Ltda, São Paulo, SP) and was available through the site http://www.cleus-encuesta.com until January 2013. To ensure confidentiality of the survey and the respondents, an account with login and a password used to access the online questionnaire was created. Responses were requested only from physicians who perform EUS. The responses were sent directly to a domain (http://www.cleus-encuesta.com).

Electronic messages were sent twice a month, before 31 January 2013 requesting the participation of the members who hadn’t responded and those with incomplete questionnaires.

The data were tabulated in an excel spreadsheet and evaluated mostly descriptively. The variables in some multiple choice questions were evaluated based on a score of frequency of responses, expressing a ranking of importance among the variables.

RESULTS

The survey was sent to 268 CLEUS’ members and 13 new registrations were made, possibly, by referral of CLEUS’ members. Therefore, among 281 physicians, 70 (25%) answered the questionnaires. Of these 70 questionnaires, 57 (81%) participants answered all mandatory questions. Of the 57 endosonographers, 41 (72%) also responded partially or all the optional questions related to cost, fees and reimbursement.

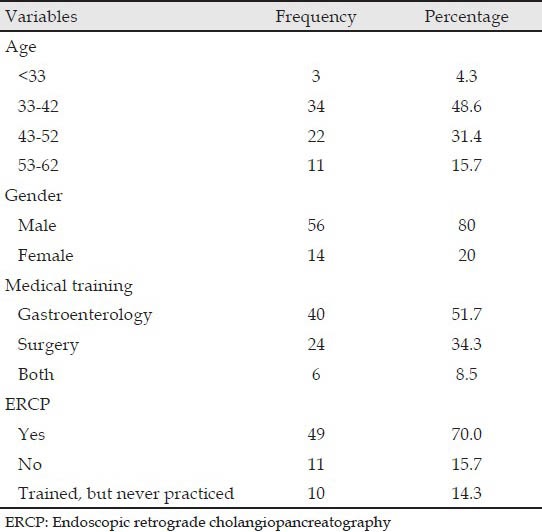

Among the LA countries, questionnaires were sent to 17 countries and one Latin territory. 12 countries and one Latin territory answered the survey, as observed in Tab. 1. The demographic characteristics of respondents are shown in Tab. 2.

Table 1.

Latin American countries represented in the survey

Table 2.

Characteristics of respondents (N = 70)

EUS practice

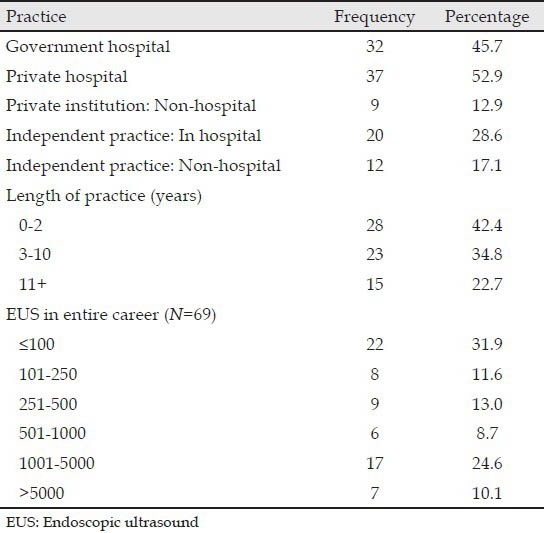

Respondents have an average of 6 years of independent practice in EUS (mode: 1 year, median: 3.5 years). Regarding the place of practice, 37 (53%) respondents are employees of private hospitals.

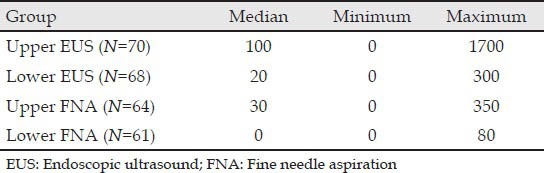

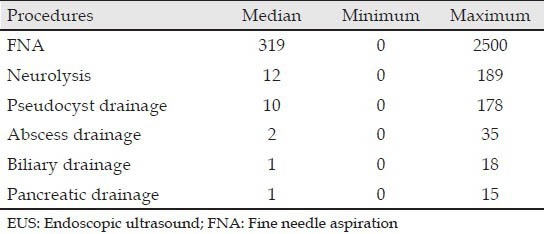

A total of 22 endosonographers performed 100 or fewer procedures in their entire career, while 17 performed between 1001 and 5000 exams. The median number of procedures performed in 2011 was: 100 upper EUS, 20 lower EUS, 30 upper fine-needle aspirations (FNA) and 0 lower FNA (Tabs. 3-5).

Table 3.

Current practice in EUS in Latin American

Table 5.

EUS numbers in 2011

Table 4.

Median of EUS procedures performed in entire career

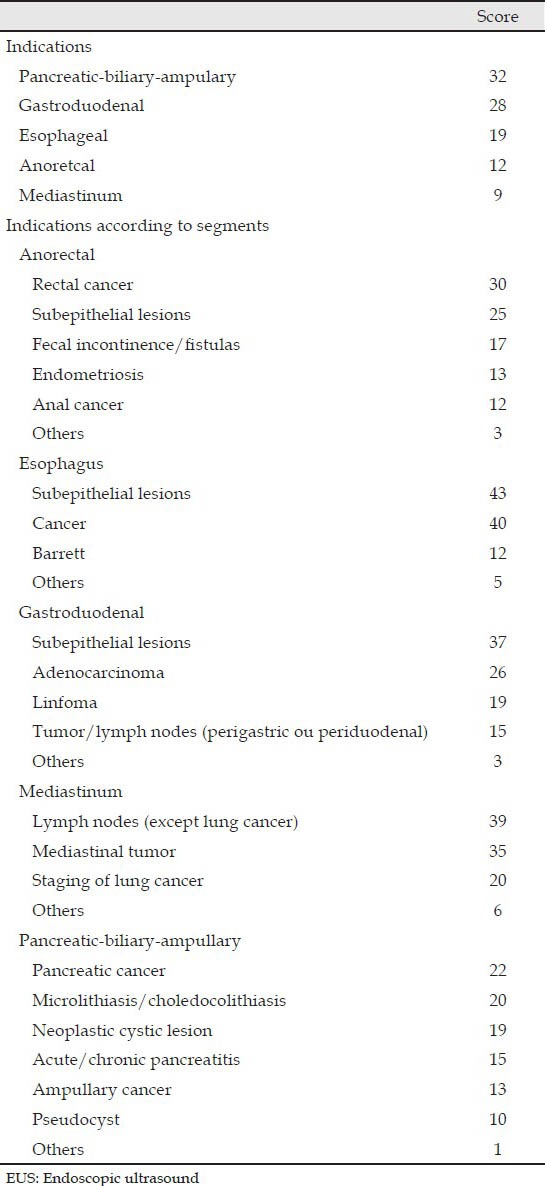

The indications for anatomical segments in order of frequency are: Pancreatic-biliary-ampulary, gastroduodenal, esophageal, anorectal and mediastinal. The most common indications for pancreatic-biliary-ampulary segment are evaluation of solid and cystic tumors of the pancreas (Tab. 6).

Table 6.

Score of indications for EUS (N = 67)

The most frequent complication related to echoendoscopic procedure is bleeding which needed treatment or hospitalization (26 occurrences from 63 respondents). When asked about sedation, nearly 82% of respondents use propofol in most or all procedures. The anesthesiologist is present in 70% of the procedures.

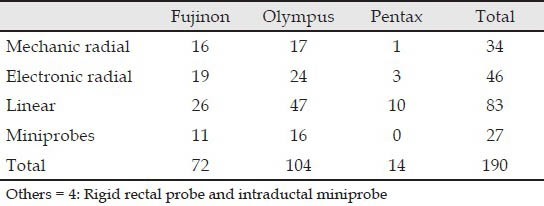

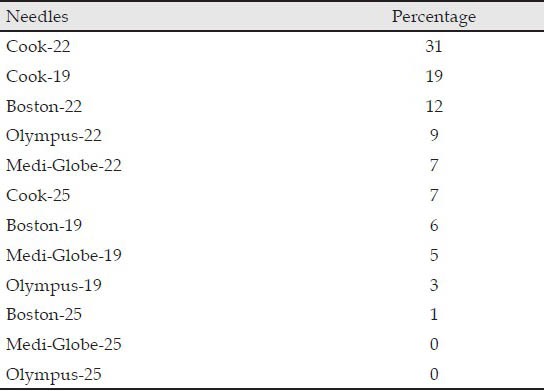

Regarding the type of equipment, the linear echoendoscope is the most used, followed by electronic radial echoendoscope. Other probes (for example, rigid rectal probe) are also used less frequently. The 22-G needle is used in most procedures. Tabs. 7 and 8 shows the combination of different endoscopes, needles and different brands available on the market.

Table 7.

Equipment used by Latin American endosonographers

Table 8.

Score of preferred needles (%)

A total of 88% of participants check the result of anatomopathology. The related average number of positive punctures to solid lesions is 80% (N = 54, average = 79.61, σ =18.53) and to cystic lesions is 70% (N = 54, average = 70.56, σ =23.89).

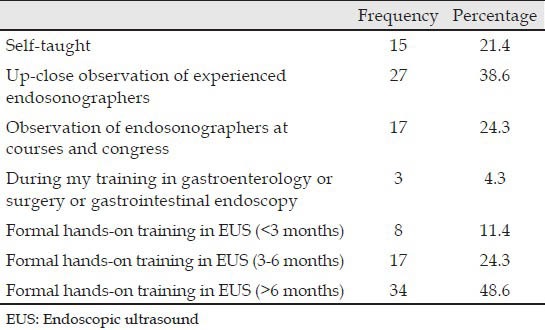

EUS training

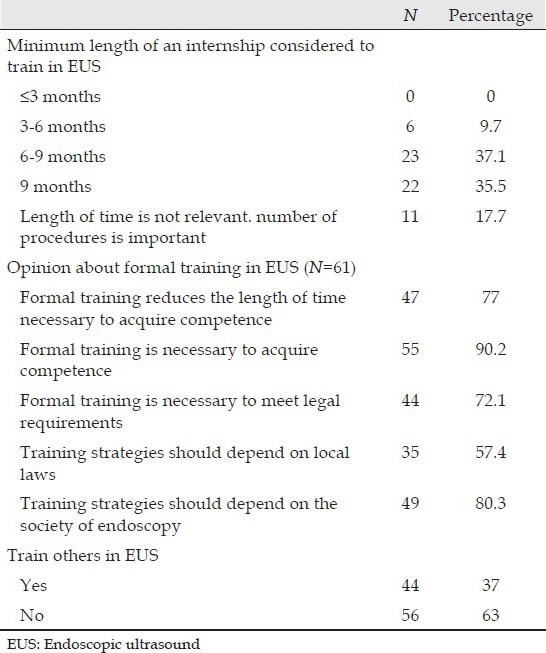

The training methods used by the participants to learn EUS are shown in Tab. 9. About 48% of respondents have more than 6 months of dedicated hands-on EUS training. The majority of respondents (56%) do not train other endoscopists in EUS. Almost 90% of respondents consider that formal training in EUS is needed to acquire competence.

Table 9.

Training methods used to learn EUS (N = 70)

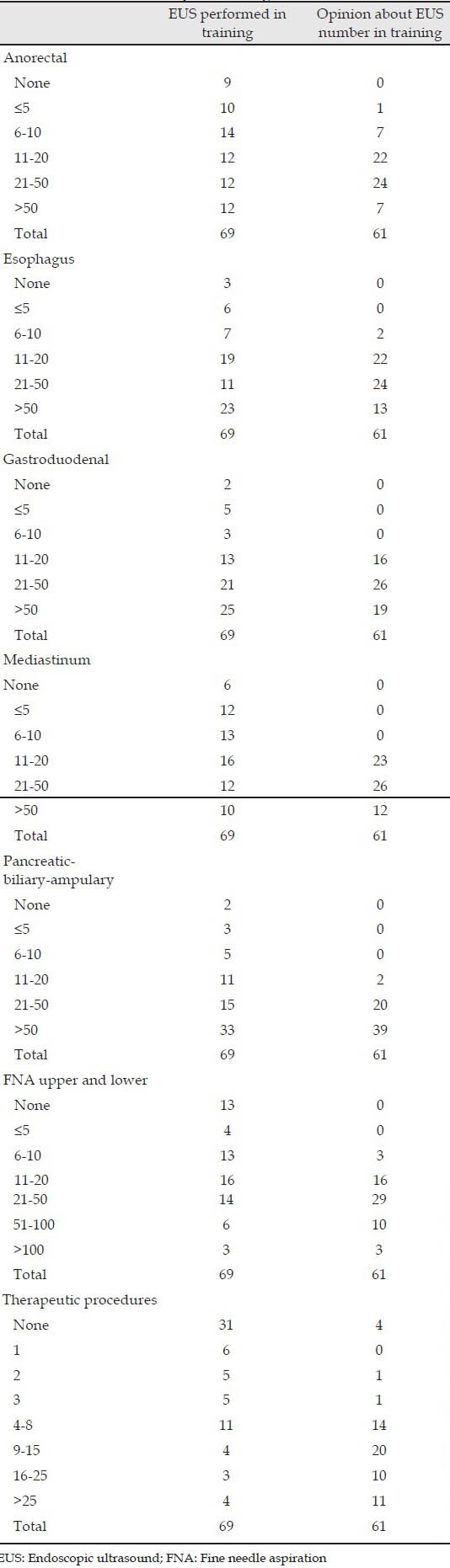

The minimum average training should be at least 6 months for 72.6% of respondents (Tab. 10). Most of the endosonographers consider that the minimum number of supervised procedures should be greater than 50 Pancreatic-biliary-ampulary, 20 anorectal, 20 FNA and nine therapeutic procedures (Tab. 11).

Table 10.

Opinion of Latin America endosonographers about training

Table 11.

Numbers of EUS performed during training versus opinion on number of EUS necessary for training

Cost, fees and reimbursement in EUS

The questions relating to reimbursement by Health Maintenance Organization show that 13 of 28 respondents did not know how much was reimbursed in diagnostic procedures and 13 of 25 respondents did not know about FNA procedures. Reimbursement by the government institution is unknown among 18 of 26 respondents for diagnostic procedures and 18 of 25 for procedures with FNA.

The average costs for EUS procedures in private practice ranges from $200 to $4000 among the respondents (N = 37). The costs with the needle ranges from $190 to $1200 (N = 39 respondents, average = $534.77 dollars, σ = 275.21). Doctors’ fee also varied considerably, ranging from $170 to $1500 (N = 35 respondents).

DISCUSSION

This is the first survey to assess EUS practice in LA with participation of 17 different countries and one Latin territory. Furthermore, it is the first survey that jointly assesses issues relating to practice, training, costs and reimbursement.

Furthermore, it is a new method among CLEUS’ members, using electronic mail to enable a large number of respondents in different countries. Other North American studies also used electronic mail as a method to reach a larger number of respondents.1,2,3,4

Although the initial number of electronic mails was considerable and the reason why only 25% of participants responded this research can possibly be explained by the fact that not all participants of CLEUS perform EUS and many of them are surgeons and gastroenterologists interested in EUS.

The largest number of Brazilians endosonographers can be possibly explained because it is the most populous country and the Human Development Index is relatively better than many LA neighbors.5,6,7 According to the annual report of the United Nations, Brazil (85th) is behind four countries in South America, Chile (40th), Argentina (45th), Uruguay (51st) and Peru (77th), ahead of Ecuador (89th) and Colombia (91st).

In 1999, in the United States, the median age was 39 years, 57% were in academic practice and 84% performed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).8 In another international study comparing the practice of international and United States respondents, the mean age of participants was 40.5 years and 89.5% were men. The majority (63.4%) were in some type of academic practice.2 In an Asian study conducted in 2006, the respondents were mostly young (median age 40 years), male (97%), practicing in public hospitals (50.7%).9

In this survey, endosonographers tend to be male, young, interventional endoscopists (perform ERCP) and in most cases were affiliated to a private institution. When compared with other studies, there is a correlation as regards endosonographers being young and mostly perform ERCP.

In 2004, an international survey proposes to determine the practice patterns of international and United States endosonographers participating in a biennial international EUS symposium. This study showed that in the United States, endosonographers are likely interventional gastroenterologists who also perform therapeutic ERCP and are more likely to perform EUS-guided interventional procedures. International endosonographers were less likely to perform ERCP and other interventional EUS procedures.2 In this study, it was not possible to perform this comparison between different countries.

In the 1999 United States survey, although the median total number of procedures ever performed was 200, 41% of respondents performed half or more of their total EUS procedures during the year prior to the survey.8 In the 2004 international survey, approximately 90% of international as well as the United States endosonographers had been performing EUS for more than 1 year and more than a third had been performing EUS for at least 5 years.2 In the 2006 Asian survey, the respondents had median experience of 5 years in EUS practices and performed a median of 500 procedures in their career.9

In this survey, most endosonographers have been performing EUS for at least 1 year. Approximately one-third of the participants had <100 procedures throughout their career. Perhaps this reflects the 42.4% of new endosssonographers trained in the last 2 years.

The vast majority of procedures are diagnostic upper EUS compared to EUS/FNA and lower EUS. Lower EUS was performed much less frequently than upper EUS, probably about the least frequent indications for the procedure and/or rectal and anal sphincter evaluation by radiologists using magnetic resonance. This is consistent with research conducted in 1999;8 However, a 2006 study assessed the level of knowledge of gastroenterologists American Society of Gastroenterology (ASGE) members about the indications of EUS in four segments: Esophagus, gastroduodenum, hepatopancreatobiliary and colorectum. A research showed that gastroenterologists who perform EUS have greater knowledge of indications of EUS. However, the levels of knowledge of colorectal applications of EUS are the poorest among the four studied organ systems. This refers to the fact that educational initiatives should focus on applications of EUS in this category.4

Regarding indications for upper EUS, pancreatobiliary segment was among the most studied and the indications in this segment are the study of cystic and solid lesions of the pancreas. In another study,8 esophagogastric and pancreatico-biliary were the most common, but there is no detail about the lesions studied in each segment.

In this study, linear echoendoscope was the most used, but when compared with radial echoendoscope (electronic and mechanic), the difference is not significant. Most participants also perform ERCP. In 2004, Das et al.2 compared North American endosonographers with other international endosonographers and showed that North Americans are more likely to use linear echoendoscope and perform ERCP more frequently. This possibly explained why North American endosonographers were the most of participants also perform ERCPs were propense to perform EUS interventional procedures are more likely to use liready likely to perform EUS-FNA and other interventional procedures. In this study, most endosonographers perform ERCP and use the linear echoendoscope, but it is not possible to conclude that there is a propensity for EUA-FNA and other interventional procedures.

The needle most used is a 22-G one. Perhaps, this reflects the fact that the indication for pancreatic segment is the most common and most studies in EUS-FNA performed in the pancreatic masses setting have been conducted using 22-G needles.10

In this study, the complication most often reported in EUS is bleeding; followed by infection and perforation. In the literature, complications associated with EUS-FNA are rare. The incidence of bleeding reported in large prospective series range between 0% and 0.5%.10

In relation to learning methods, the majority of respondents had a formal training of 6 months or more in EUS after graduating in fellowship programs in gastroenterology or gastrointestinal endoscopy. This can be a reflection that new strategies are being put in place and newly trained endosonographers have a well-established training program than older endosonographers who did their training mainly in France, USA, Japan and Germany. In LA, few training centers came into being in recent years, for instance, Centro Franco-Brasileiro de Ecoendoscopia in Brazil and Clinica Alemana in Chile. About 24% of endosonographers also learned EUS observing other more experienced physicians. This may be related to the fact that even younger endosonographers spend a period during their training programs in other centers outside LA.

Even in Europe, the combination of two methods of learning EUS is practice; consisting of dedicated fellowship program and informal training (short repeated exposures to “hands-on” experiences).10

In this study, 44% of endosonographers train others in EUS. This number does not differ much from what was seen in the study published in 1999 with the United States endosonographers, where 40% trained other doctors.

Nearly 90% of participants agree that formal training is necessary to acquire competence, 80% think that training strategies must depend upon local endoscopy societies and 73% of respondents consider a time period longer than 6 months to acquire competence. In addition, during the training program, a minimum number of procedures for each anatomical segments, FNA and therapeutic procedure are indicated by the respondents.

Thus, as ERCP, learning in EUS is considered technically more demanding and there is a variation in individual learning curve that should be evaluated by criteria goals. Currently, there is no consensus on the number of procedures required to acquire competence. The ASGE guidelines published in 2006 states the minimum number of procedures: 75 cases of esophagus, stomach and rectum tumors; 40 cases of submucosal abnormalities; 75 pancreatobilliary cases; 25 EUS-FNA (non-pancreatic) and 25 EUS-FNA (pancreatic). The competence recommended generally in all aspects of EUS would be a minimum of 150 supervised cases, of which, 75 should be pancreatobilliary and 50 EUS-FNA. Trainees may start performing EUS-FNA after 50 procedures or more.11,12

A study in the Asia-Pacific region also considered that there should be a median number of 100 supervised procedures with a minimum of 6 months training. Most respondents (90%) also believe that formal internship is necessary to acquire competence.9

As a result, new training strategies become imperative and each country should implement more appropriate training orientations to ensure quality in training and clinical practice of EUS in LA.

Insufficient statistical data did not allow us to reach a conclusion regarding costs, fees and reimbursement. This is because, 58 of the participants answered the questions related to these topics, about half of the respondents had no knowledge as regards refund of EUS procedures and there are different payment systems in different countries in LA.

The questionnaires were sent to all CLEUS’ members and there was an increase in the sample through the E-mails sent to non-members. Therefore, there are limitations in the methodology of this research, as we do not know accurately the number of doctors who perform EUS in LA and it is unlikely that all endosonographers have responded this survey. Furthermore, it is likely that some respondents did not participate in the survey because they do not perform a large number of procedures.

Even sending reminders over the months in which the research was online, some doctors may not have received the questionnaire due to the limitations of the tool used for dissemination (incorrect addresses, the presence of anti-spam, among others).

CONCLUSION

This study provides an overview on the status of EUS in LA and from our standpoint, the greatest contribution of this study is the perception of the need to standardize EUS training strategies in LA.

APPENDIX

REFERENCES

- 1.Azad JS, Verma D, Kapadia AS, et al. Can U.S. GI fellowship programs meet American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommendations for training in EUS?. A survey of US GI fellowship program directors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das A, Mourad W, Lightdale CJ, et al. An international survey of the clinical practice of EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:765–70. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buscaglia JM, Shin EJ, Giday SA, et al. Awareness of guidelines and trends in the management of suspected pancreatic cystic neoplasms: Survey results among general gastroenterologists and EUS specialists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:813–20. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.036. 8201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yusuf TE, Harewood GC, Clain JE, et al. International survey of knowledge of indications for EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:107–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Human Development Reports. Posted by Program of United Nations Development (UNDP) [Last accessed on 2013 Aug 04]. Available from: http://www.hdr.undp.org .

- 6.Posted by Program of United Nations Development (UNDP); [Last accessed on 2013 Aug 04]. The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World. Human Development Report 2013. Available from: http://www.pnud.org.br/arquivos/rdh-2013.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brasil tem salto de 47,8% no Índice de Desenvolvimento Humano Municipal entre 1991 e. 2010. [Last accessed on 2013 Aug 04]. Available from: http://www2.planalto.gov.br .

- 8.Savides TJ, Fisher AH, Jr, Gress FG, et al. 1999 ASGE endoscopic ultrasound survey. ASGE Ad Hoc Endoscopic Ultrasound Committee. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:745–50. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.109805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho KY. Survey of endoscopic ultrasonographic practice and training in the Asia-Pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1231–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polkowski M, Larghi A, Weynand B, et al. Learning, techniques, and complications of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling in gastroenterology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2012;44:190–206. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang KJ. EUS-guided FNA: The training is moving. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:69–73. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisen GM, Dominitz JA, Faigel DO, et al. Guidelines for credentialing and granting privileges for endoscopic ultrasound. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:811–4. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(01)70082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]