Abstract

Host defense is an orchestrated response involving changes in the expression of receptors and release of mediators from both immune and structural cells. There is a growing recognition of the important role of proteolytic pathways for the protective immune response to enteric pathogens. Enteric nematode infection induces a type 2 immune response with polarization of macrophages toward the alternatively activated phenotype (M2). The Th2 cytokines, IL-4, and IL-13, induce a STAT6-dependent upregulation of the expression of the protease inhibitor, serpinB2, which protects macrophages from apoptosis. M2 are critical to worm clearance and a novel role for serpinB2 is its regulation of the chemokine, CCL2, which is necessary for monocyte and/or macrophage influx into small intestine during infection. There is a growing list of factors including immune (LPS, Th2 cytokines) as well as hormonal (gastrin, 5-HT) that are linked to increased expression of serpinB2. Thus, serpinB2 represents an immune regulated factor that has multiple roles in the intestinal mucosa.

Keywords: enteric nematode infection, Th2 cytokines, macrophage, serpinB2, plasminogen activation system

Proteolytic Pathways and Immunity

Approximately 4.5% of the human genome encodes proteases (~1200 genes),1 which perform a variety of functions throughout the body and regulate a wide range of developmental, physiological and disease associated processes. Proteases are important for the conversion of inactive forms of many proteins into their active counterparts, for the breakdown of proteins and for host defense against intruding pathogens. Many proteases are components of proteolytic cascades, where the product from one reaction acts as the substrate for the next, effectively amplifying the initial signal to enhance the response. Regulatory proteolysis is a highly conserved process from microbes to humans and is emerging as a focal point for therapeutic intervention.2 Most pathogens, including bacteria, mites, viruses, and nematodes, elaborate proteases that play a key role in their survival in the host.2-6

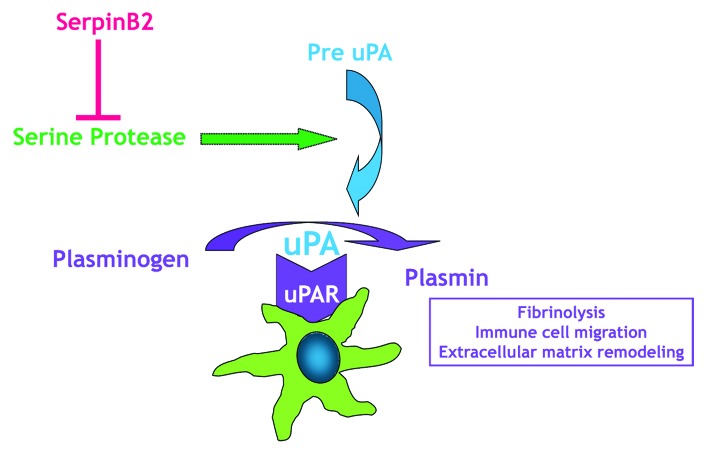

Proteases are classified into six broad groups, serine proteases, threonine proteases, aspartate proteases, glutamic proteases, cysteine proteases, and metalloproteases, depending on the nature of their catalytic mechanism. The proteolytic activity in the cellular microenvironment modulates a number of critical processes including proliferation, migration, differentiation, and apoptosis. Recent studies also implicate a role for proteolytic pathways in immune responses.7-9 The class of serine proteases is one of the most intensely studied groups of enzymes and includes secreted, receptor-bound and transmembrane proteases. The plasminogen activation system (uPA system, Fig. 1) is a prototypic receptor bound protease system important for controlling fibrinolysis.13 In this system, plasminogen is cleaved to plasmin by two proteases, tissue-type or urokinase-type plasminogen activators (tPA or uPA). uPA localizes to the cell surface by binding its receptor, uPAR, where a well-known function of uPA activation is turnover of the extracellular matrix through direct proteolysis. Cells in the innate immune system use the uPA system for inflammatory migration by upregulating the production of uPA and uPAR. In vivo investigation of the role that uPA plays in host defenses was hampered initially by the inability to completely and irreversibly eliminate uPA. The development of transgenic mice lacking the uPA gene,10 however, demonstrated the importance of this gene as uPA−/− mice are more susceptible to infection by pathogens that induce either a type 1 or type 2 response.11,12 In these studies, uPA−/− mice showed impaired T lymphocyte proliferative responses resulting in significant decrease in cytokine expression.

Figure 1. Macrophages express the components of the urokinase plasminogen activation system. Serine proteases activate pre-uPA (the uPA zymogen) to uPA, which then binds to uPAR, and efficiently activates plasminogen to the enzyme plasmin, localizing it to the plasma membrane. Plasmin is important to a number of functions including immune cell migration. By inhibiting uPA, serpinB2 can block plasminogen activation.

In recognition of the importance of regulating protease activities, protease inhibitors have evolved in parallel with the proteases they regulate. Members of the serine protease inhibitor (serpin) superfamily have a unique mechanism for blocking protease activity. Inhibitory serpins function as “decoy molecules” or “suicide substrates” because they resemble the substrate targets of specific proteases. Once the protease cleaves the serpin, it becomes irreversibly trapped in a serpin-protease complex and this interaction leads to distortion of the active site on the enzyme. Thus, serpins act as “protease sinks,” removing active enzyme to limit or prevent damage to local cells or to tissue.

Immune Functions of Protease Inhibitors

The pericellular proteolytic activity of uPA is regulated by plasminogen activator inhibitors (PAI), PAI-1 and PAI-2 (formally named serpinE1 and serpinB2, respectively). Expression of serpinB2 is limited to a few cell types and may be subject to cell-specific molecular mechanisms that regulate its expression. Upregulation of serpinB2 is observed in a number of inflammatory pathologies including enteric pathogen infection.13-15 SerpinB2-mediated inhibition of uPA is important in the regulation of extracellular plasminogen-dependent proteolysis and the increased expression of serpinB2 in carcinoma is consistent with its ability to inhibit uPA-mediated metastatic activity.16 The extracellular concentration of the glycosylated 60kDA form of serpinB2 increases during inflammation, yet the majority of the serpinB2 synthesized is not found glycosylated.17 Recent evidence indicates that the nonglycosolyated 47kDa intracellular form can be released from endothelial cells in response to LPS by a mechanism involving the formation of secretory vesicles.18 In many cells, however, serpinB2 accumulates intracellularly and is not secreted.17 The function of this intracellular form may be unrelated to its role as a protease inhibitor, thereby expanding the classical extracellular molecular role for serpinB2. Indeed, the intracellular form has an emerging role in modulating both innate and adaptive immunity. An early pertinent observation was that TNFα upregulated the expression of serpinB2 indicating a protective role for intracellular serpinB2 against TNFα-induced apoptosis in fibrosarcoma cells.19 These findings were confirmed subsequently in other cell lines20,21 including immune cells.22

SerpinB2 and Macrophage Function

Immune cells possessing serpins include granulocytes, monocytes, and cytotoxic lymphocytes. Intestinal macrophages play a prominent role in mucosal homeostasis, and along with dendritic cells, are considered to be key effector cells in the innate immune system first line of defense. An important feature of macrophages is the ability to respond to a variety of stimuli produced in response to pathogen infection. Macrophages can undergo classical activation (M1) in the presence of a strong Th1 cytokine environment such as that in microbial infection. In the context of a strong Th2 cytokine environments, including enteric nematode infection, macrophages undergo alternative activation (M2).23 Macrophages are critical for the full development of a Th2 response and the elimination of M2 impairs worm clearance and the associated changes in gut smooth muscle function that facilitate expulsion.24,25 Although GM-CSF and M-CSF both contribute to macrophage development, GM-CSF drives the polarization to M1 while M-CSF promotes polarization to M2. SerpinB2 is one of the most inducible macrophage gene products induced by the Th1 promoting factor LPS, with induction reported over 105-fold16,26 and has innate immune functions that are critical to macrophage survival.22 SerpinB2 deficient mice do not have an obvious phenotype but exhibit impaired responses to infections.13,15,27

Macrophage expression of serpinB2 is upregulated by LPS through a mechanism involving CREB and NFκB and is important for the maintenance of TLR4 activation, thereby preventing rapid macrophage death and premature cessation of the innate immune response.22 Indeed, LPS-induced upregulation of serpinB2 was dependent upon the formation of CCAAT enhancer binding (C/EBP)-β complexes with the serpinB2 promoter.28 C/EBP is one of a number of ERK1/2 regulated transcription factors that is instrumental in macrophage activation and polarization. There is also evidence that serpinB2 plays a role in adaptive immune responses. Macrophage serpinB2 production is upregulated highly during microbial, viral and nematode infections.13,27,29 Recent studies have implicated an anti-inflammatory role for serpinB2 and it is considered to be part of the M2-associated genes.15,30

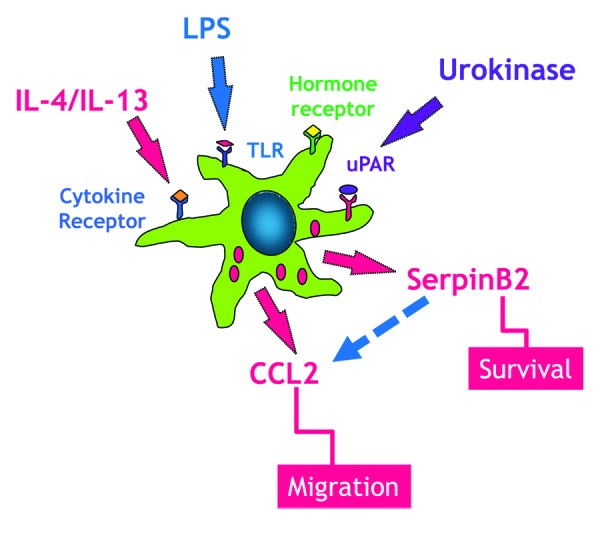

In response to enteric pathogens, cytokine-induced upregulation of specific chemokines are involved in the recruitment of additional circulating monocytes to the intestine and differentiation of these infiltrating macrophages including monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) also known as chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2). CCL2 is a member of the C-C chemokine family and is produced by many types of cells including epithelium, endothelium, smooth muscle, and fibroblasts. The major source of CCL2, however, is macrophages and this chemokine has emerged as a potential therapeutic target in a number of autoimmune diseases. Notably, loss of CCL2 alone may impact monocyte recruitment in some inflammatory pathologies.31 A recent study demonstrated that serpinB2 deficient mice fail to upregulate expression of CCL2 and the M2 marker, arginase-1, at day 12 post a memory response to Heligmosoimoides bakeri (H. bakeri) infection, leading to impaired macrophage infiltration and alternative activation of macrophages, resulting in impaired worm expulsion.15 There is evidence that CCL2 deficient mice also have an impaired ability to mount a type 2 immune response consistent with a delayed worm expulsion in H. bakeri infection.15 Mice deficient in CCL2 do not have reduced numbers of resident macrophages but fail to recruit macrophages in response to stimulation. Importantly, CCL2 deficient mice retained their resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection showing that the type 1 response was intact.32 While it was proposed that this effect could be mediated by a direct effect of CCL2 on T cells, it is also possible that the macrophages recruited early in the post infection period release IL-13 that acts to promote an early type 2 response. Indeed, we and others demonstrated that macrophages have the ability to generate IL-13 in response to IL-25,33 an epithelial-derived cytokine that promotes the M2 phenotype, as well in response to respiratory syncytial virus.34,35 These data link serpinB2 expression and macrophage activation during the development of Th2-mediated protective immunity (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Macrophages express a number of receptors including TLR, cytokine, and hormones that have been linked to the upregulation of serpinB2 expression, which is linked to macrophage survival. During enteric nematode infection resident macrophages respond to IL-4/IL-13 to develop into the alternatively activated phenotype (M2). These resident macrophages elaborate CCL2, a key chemokine in monocyte recruitment to the small intestine. SerpinB2 expression is necessary for the effective generation of macrophage CCL2.

Immune Regulation of SerpinB2 Expression

The mechanisms that regulate serpinB2 expression during infection have not been elucidated fully. There are seven signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family members and each STAT responds to specific cytokines leading to induction of gene expression.36 Studies in H. bakeri-infected mice show that the upregulation of serpinB2 expression is dependent on STAT6, the transcription factor used exclusively by IL-4 and IL-13. Activation is tightly regulated and there is evidence also that proteases can regulate STAT6.37,38 Indeed, a “STAT6 protease” in the nucleus of murine mast cells is required for cleavage of an inactive form of STAT6, STAT6β, to the active form.39,40 The infiltration and development of the M2 phenotype during nematode infection is STAT6-dependent.25 Zhao et al. reported recently that the upregulation of serpinB2 expression in response to nematode infection is STAT6-dependent, adding serpinB2 to the growing list of genes controlled by STAT6 including arginase-1 and CD206 (mannose receptor) that regulate macrophage function.24,25 In addition, there is a STAT6-mediated upregulation of the expression of two protease-activated receptors (PAR), PAR1 and PAR2, during nematode infection.8,41 How serpinB2 activity may regulate these pathways is unknown, but an intriguing interaction among these factors is illustrated by the observation that activation of PAR2 increases serpinB2 expression.42 Together, these observations serve to emphasize the extensive contribution of proteolytic factors to immune cell function.

Emerging Mechanisms in the Control of SerpinB2 Expression

The gastrointestinal tract is the largest endocrine organ in the body. Hormones are elaborated and released from specialized cells that line the gut called enteroendocrine cells. This endocrine control is highly integrated with that exerted by the enteric nervous system fueling the long-standing interest in the neuroendocrine contribution to host defense against pathogens. Hormones such as gastrin and the amine serotonin (5-HT) exert multiple actions on the gut and are implicated in host defense against pathogens including Helicobacter pylori43 and Salmonella typhmurium.44 Helicobacter pylori infection increased the release of gastrin, which has trophic effects that are important for mucosal defense and regeneration of the gastric mucosa. Of interest is that previous studies demonstrated an NFκB-mediated increase in serpinB2 expression in gastric mucus producing cells during Helicobacter pylori infection.14 Gastrin is linked to inflammation via the CCK-2 receptor expressed on specific cell types such as cancer cells, enterochromaffin cells, parietal cells, macrophages, and neutrophils.45 Binding of gastrin to the CCK2 receptors on AGS cells (a human stomach cancer cell line) overexpressing CCK-2 upregulates the expression of serpinB2 through a proteosome β subunit, PSMB1.43 These data suggest a link between CCK-2 and increased serpinB2 expression to the effects of gastrin on maintenance of epithelial integrity, but this observation remains to be investigated in vivo.

The largest concentration of 5-HT is in enteroendocrine cells. There are numerous 5HT receptors (5-HT1–7) that mediate the effects of 5-HT on gastrointestinal functions as well as cardiovascular cells. Several of these receptors are located also on immune cells, including macrophages, and are involved in inflammation and tissue regeneration. Of interest is that 5-HT binding to primarily 5-HT7, but also to 5HT2b receptors, on macrophages upregulates serpinB2 expression and promotes the maintenance of the M2 phenotype.30 There is also data showing the immune regulation of 5-HT receptors on macrophages during nematode infection.46 These data further emphasize the importance of serpinB2 as a modulator of macrophage function in response to variety of stimuli.

Conclusions

Enteric nematode infection induces stereotypic alterations in gut function that are orchestrated by the interactions of immune and structural cells (e.g., epithelial cells) that are linked to IL-4/IL-13 activation of STAT6 signaling pathways. Macrophages express a number of protease receptors including PAR1, PAR2, and uPAR. The balance among proteases and inhibitors, including uPA and serpinB2, is critical for infiltration and migration of macrophages into tissue and for protection of macrophages from apoptosis. As macrophages are part of the first line of defense against enteric pathogens, factors that control their longevity and influx are critical to a protective host response. The polarization of M2 during nematode infection induces a STAT6-dependent upregulation of serpinB2 expression. SerpinB2 is emerging as a novel regulator of macrophage survival and deficiency in serpinB2 is linked to impaired CCL2-mediated macrophage influx into small intestine. There is a growing list of factors including immune (LPS, Th2 cytokines) as well as hormonal (gastrin, 5-HT) that are linked to increased expression of serpinB2. Thus, serpinB2 represents an immune regulated factor that has multiple roles in the intestinal mucosa.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01-AI/DK49316 (T.S-D.), R01-DK083418 (A.Z.), and R01-DK081376 and R56-CA098369 (T.M.A.).

References

- 1.Shpacovitch V, Feld M, Hollenberg MD, Luger TA, Steinhoff M. Role of protease-activated receptors in inflammatory responses, innate and adaptive immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1309–22. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0108001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raju RM, Goldberg AL, Rubin EJ. Bacterial proteolytic complexes as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:777–89. doi: 10.1038/nrd3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasnain SZ, McGuckin MA, Grencis RK, Thornton DJ. Serine protease(s) secreted by the nematode Trichuris muris degrade the mucus barrier. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison J, Aguirre S, Fernandez-Sesma A. Innate immunity evasion by Dengue virus. Viruses. 2012;4:397–413. doi: 10.3390/v4030397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun Y, Liu G, Li Z, Chen Y, Liu Y, Liu B, Su Z. Modulation of dendritic cell function and immune response by cysteine protease inhibitor from murine nematode parasite Heligmosomoides polygyrus. Immunology. 2013;138:370–81. doi: 10.1111/imm.12049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips C, Coward WR, Pritchard DI, Hewitt CRA. Basophils express a type 2 cytokine profile on exposure to proteases from helminths and house dust mites. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:165–71. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0702356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devlin MG, Gasser RB, Cocks TM. Initial support for the hypothesis that PAR2 is involved in the immune response to Nippostrongylus brasiliensis in mice. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:105–9. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shea-Donohue T, Notari L, Stiltz J, Sun R, Madden KB, Urban JF, Jr., Zhao A. Role of enteric nerves in immune-mediated changes in protease-activated receptor 2 effects on gut function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:1138–e291. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao A, Shea-Donohue T. PAR-2 agonists induce contraction of murine small intestine through neurokinin receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G696–703. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00064.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmeliet P, Schoonjans L, Kieckens L, Ream B, Degen J, Bronson R, De Vos R, van den Oord JJ, Collen D, Mulligan RC. Physiological consequences of loss of plasminogen activator gene function in mice. Nature. 1994;368:419–24. doi: 10.1038/368419a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gyetko MR, Sud S, Chen GH, Fuller JA, Chensue SW, Toews GB. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator is required for the generation of a type 1 immune response to pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Immunol. 2002;168:801–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gyetko MR, Sud S, Chensue SW. Urokinase-deficient mice fail to generate a type 2 immune response following schistosomal antigen challenge. Infect Immun. 2004;72:461–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.461-467.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroder WA, Gardner J, Le TT, Duke M, Burke ML, Jones MK, McManus DP, Suhrbier A. SerpinB2 deficiency modulates Th1⁄Th2 responses after schistosome infection. Parasite Immunol. 2010;32:764–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2010.01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varro A, Noble P-JM, Pritchard DM, Kennedy S, Hart CA, Dimaline R, Dockray GJ. Helicobacter pylori induces plasminogen activator inhibitor 2 in gastric epithelial cells through nuclear factor-kappaB and RhoA: implications for invasion and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1695–702. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao A, Yang Z, Sun R, Grinchuk V, Netzel-Arnett S, Anglin IE, Driesbaugh KH, Notari L, Bohl JA, Madden KB, et al. SerpinB2 is critical to Th2 immunity against enteric nematode infection. J Immunol. 2013;190:5779–87. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medcalf RL. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 2: still an enigmatic serpin but a model for gene regulation. Methods Enzymol. 2011;499:105–34. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386471-0.00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahony D, Kalionis B, Antalis TM. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type-2 (PAI-2) gene transcription requires a novel NFkappaB-like transcriptional regulatory motif. Eur J Biochem. 1999;263:765–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boncela J, Przygodzka P, Wyroba E, Papiewska-Pajak I, Cierniewski CS. Secretion of SerpinB2 from endothelial cells activated with inflammatory stimuli. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:1213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar S, Baglioni C. Protection from tumor necrosis factor-mediated cytolysis by overexpression of plasminogen activator inhibitor type-2. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20960–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fish RJ, Kruithof EKO. Evidence for serpinB2-independent protection from TNFalpha-induced apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:350–61. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stringer B, Udofa EA, Antalis TM. Regulation of the human plasminogen activator inhibitor type 2 gene: cooperation of an upstream silencer and transactivator. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:10579–89. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.318758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park JM, Greten FR, Wong A, Westrick RJ, Arthur JS, Otsu K, Hoffmann A, Montminy M, Karin M. Signaling pathways and genes that inhibit pathogen-induced macrophage apoptosis--CREB and NFkappaB as key regulators. Immunity. 2005;23:319–29. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anthony RM, Urban JF, Jr., Alem F, Hamed HA, Rozo CT, Boucher JL, Van Rooijen N, Gause WC. Memory T(H)2 cells induce alternatively activated macrophages to mediate protection against nematode parasites. Nat Med. 2006;12:955–60. doi: 10.1038/nm1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao A, Urban JF, Jr., Anthony RM, Sun R, Stiltz J, van Rooijen N, Wynn TA, Gause WC, Shea-Donohue T. Th2 cytokine-induced alterations in intestinal smooth muscle function depend on alternatively activated macrophages. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:217–25, e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki T, Hashimoto S, Toyoda N, Nagai S, Yamazaki N, Dong HY, Sakai J, Yamashita T, Nukiwa T, Matsushima K. Comprehensive gene expression profile of LPS-stimulated human monocytes by SAGE. Blood. 2000;96:2584–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schroder WA, Le TTT, Major L, Street S, Gardner J, Lambley E, Markey K, MacDonald KP, Fish RJ, Thomas R, et al. A physiological function of inflammation-associated SerpinB2 is regulation of adaptive immunity. J Immunol. 2010;184:2663–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Udofa EA, Stringer BW, Gade P, Mahony D, Buzza MS, Kalvakolanu DV, Antalis TM. The transcription factor C/EBP-β mediates constitutive and LPS-inducible transcription of murine SerpinB2. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darnell GA, Schroder WA, Gardner J, Harrich D, Yu H, Medcalf RL, Warrilow D, Antalis TM, Sonza S, Suhrbier A. SerpinB2 is an inducible host factor involved in enhancing HIV-1 transcription and replication. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31348–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de las Casas-Engel M, Domínguez-Soto A, Sierra-Filardi E, Bragado R, Nieto C, Puig-Kroger A, Samaniego R, Loza M, Corcuera MT, Gómez-Aguado F, et al. Serotonin skews human macrophage polarization through HTR2B and HTR7. J Immunol. 2013;190:2301–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu B, Rutledge BJ, Gu L, Fiorillo J, Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL, North R, Gerard C, Rollins BJ. Abnormalities in monocyte recruitment and cytokine expression in monocyte chemoattractant protein 1-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1998;187:601–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu L, Tseng S, Horner RM, Tam C, Loda M, Rollins BJ. Control of TH2 polarization by the chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Nature. 2000;404:407–11. doi: 10.1038/35006097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Z, Grinchuk V, Urban JF, Jr., Bohl J, Sun R, Notari L, Yan S, Ramalingam T, Keegan AD, Wynn TA, et al. Macrophages as IL-25/IL-33-responsive cells play an important role in the induction of type 2 immunity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shirey KA, Pletneva LM, Puche AC, Keegan AD, Prince GA, Blanco JCG, Vogel SN. Control of RSV-induced lung injury by alternatively activated macrophages is IL-4R alpha-, TLR4-, and IFN-beta-dependent. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3:291–300. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shirey KA, Cole LE, Keegan AD, Vogel SN. Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain induces macrophage alternative activation as a survival mechanism. J Immunol. 2008;181:4159–67. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shea-Donohue T, Fasano A, Smith A, Zhao A. Enteric pathogens and gut function: Role of cytokines and STATs. Gut Microbes. 2010;1:316–24. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.5.13329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanson EM, Dickensheets H, Qu CK, Donnelly RP, Keegan AD. Regulation of the dephosphorylation of Stat6. Participation of Tyr-713 in the interleukin-4 receptor alpha, the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1, and the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3903–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zamorano J, Rivas MD, Setien F, Perez-G M. Proteolytic regulation of activated STAT6 by calpains. J Immunol. 2005;174:2843–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakajima H, Suzuki K, Iwamoto I. Lineage-specific negative regulation of STAT-mediated signaling by proteolytic processing. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:375–80. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(03)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki K, Nakajima H, Ikeda K, Tamachi T, Hiwasa T, Saito Y, Iwamoto I. Stat6-protease but not Stat5-protease is inhibited by an elastase inhibitor ONO-5046. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309:768–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao A, Morimoto M, Dawson H, Elfrey JE, Madden KB, Gause WC, Min B, Finkelman FD, Urban JF, Jr., Shea-Donohue T. Immune regulation of protease-activated receptor-1 expression in murine small intestine during Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection. J Immunol. 2005;175:2563–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suen JY, Gardiner B, Grimmond S, Fairlie DP. Profiling gene expression induced by protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) activation in human kidney cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Hara A, Howarth A, Varro A, Dimaline R. The role of proteasome beta subunits in gastrin-mediated transcription of plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 and regenerating protein1. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Essien BE, Grasberger H, Romain RD, Law DJ, Veniaminova NA, Saqui-Salces M, El-Zaatari M, Tessier A, Hayes MM, Yang AC, et al. ZBP-89 regulates expression of tryptophan hydroxylase I and mucosal defense against Salmonella typhimurium in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1466–77, e1-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alvarez A, Ibiza S, Hernández C, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Esplugues JV, Calatayud S. Gastrin induces leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in vivo and contributes to the inflammation caused by Helicobacter pylori. FASEB J. 2006;20:2396–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5696fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao A, Urban JF, Jr., Morimoto M, Elfrey JE, Madden KB, Finkelman FD, Shea-Donohue T. Contribution of 5-HT2A receptor in nematode infection-induced murine intestinal smooth muscle hypercontractility. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:568–78. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]