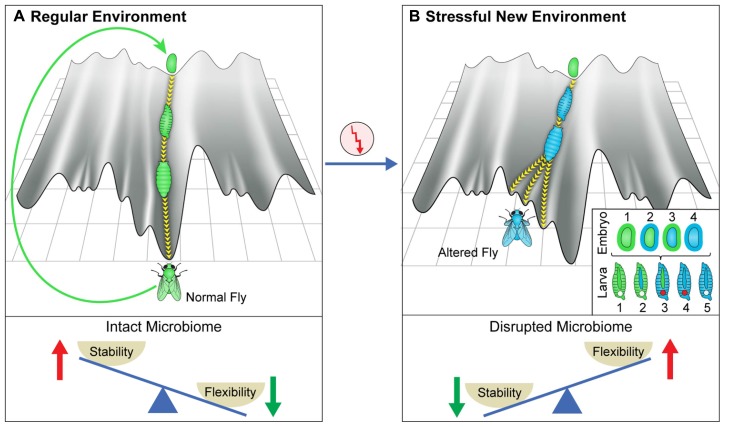

FIGURE 1.

Canalization and its disruption by stressful environments. (A) Schematic depiction of the epigenetic landscape metaphor, viewing the process of development of an organism (e.g., fly) as a movement down a canal in epigenetic landscape. The landscape depends on the host genome and its environment, including its microbiome (which can be viewed as an internal environment). The canal represents the stage-dependent processes preventing deviations from the regular patterns of development in an environment to which the organism is adapted. The deeper the canal, the more robust are the patterns. The movement is perpetuated over generations by generating a fertilized egg positioned at the top of the same canal. (B) De-canalization by exposure to a stressful new environment. In this example, the change in the environment modifies the epigenetic landscape and increases the propensity of moving within a different canal. This can result in altered somatic tissues, altered germline and altered microbiome. Inset provides color-coded representation of various potential changes in the embryos and larval stages of a developing fly that has been exposed to a new stressful external environment. The gut microbiome is represented by the outer layer of the egg and the tube in the larva. The early embryo corresponds to the inner part of the egg and the germline is represented by the circle in larva. A change in color corresponds to alteration in the respective organ following the change in the external environment. (Bottom) Proposed, context-dependent influence of the microbiome on stability/flexibility. The microbiome contributes to stabilization in the regular environment to which the organism is well adapted (left). Disruption of the microbiome in a sufficiently stressful environment (right) destabilizes the host, thereby increasing phenotypic variability (increased flexibility).