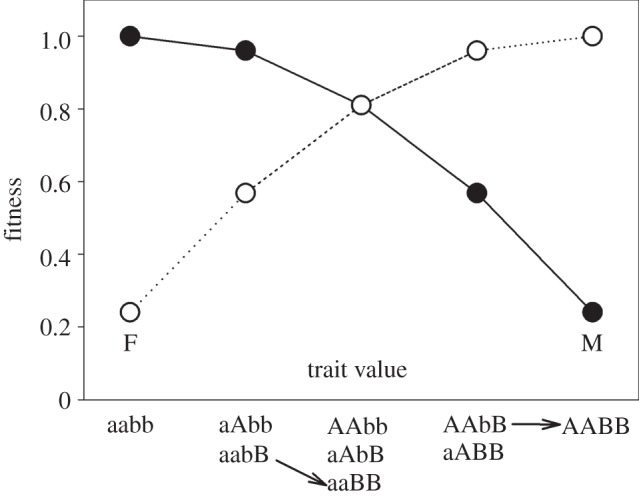

Figure 1.

Epistasis for fitness emerges as a result of concave fitness functions even when allelic effects on traits are additive. This figure shows two bi-allelic loci that affect an arbitrary life-history trait in both sexes, where A and B are favoured in females and a and b in males. Here, allelic effects on the trait are purely additive in both loci. We make two points. First, the fitness effects of any single allelic transition will depend on the genetic background. For example, a transition from bB to BB in females (open circles) will have a much stronger fitness effect in the aa genetic background (left-hand arrow) than the AA background (right-hand arrow). Second, when selection is SA, epistasis acts to ‘even the odds’ in this genetic tug-of-war. For example, when the male benefit allele at locus A is common or fixed in a population, selection for the transition bB to BB (left-hand arrow) will be stronger in females than against this transition in males (filled circles). By contrast, when the female benefit allele at locus A is instead common or fixed in a population, selection for the same transition (right arrow) will be weaker in females than against this transition in males (filled circles). Thus, selection in one locus in a particular sex is relaxed when alleles at other loci that benefit that sex increase in frequency. The scenario visualized here represents a case where sAm = sBm = sAf = sBf = 0.2, hAm = hBm = hAf = hBf = 0.2 and ɛm = ɛf = −0.1 (table 1).