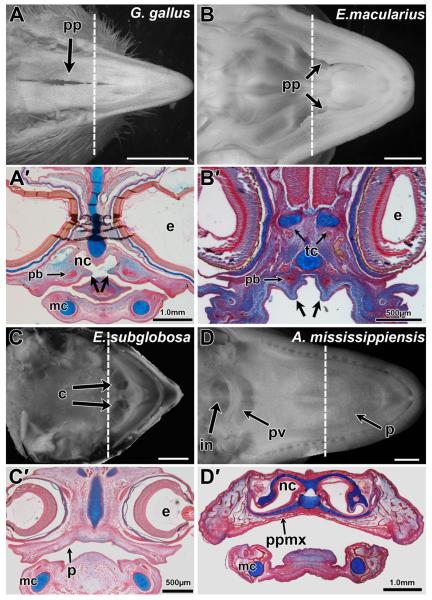

Figure 1.

Palatal phenotypes in reptiles. Palatal views of late stage reptile embryos prior to hatching (A,B) and corresponding histological sections from embryos (A’–D’). Chicken (Gallus gallus) A-stage 41 and A’-stage 34 Leopard gecko (Eublepharis macularius, C,D) B-stage 41 and B’-stage 31 (Wise et al., 2009). Turtle (Emydura subglobosa) C-stage 14 and C’-stage 5 (Werneburg et al., 2009). Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) D-stage 24 and D’-stage 23 (Ferguson, ’85). Palatine processes and the partially clefted palate can be observed in the chicken and leopard gecko while turtles lack any such processes (A,A’,B,B’,C,C’). Alligators (D,D’) have a complete secondary palate which separate the oral and nasal cavities entirely, with the internal nares opening towards the back of the mouth as in mammals. Frontal sections were stained with alcian blue and picrosirius red, showing the presence of palatine processes in the oral cavity (plane of section is shown by the dashed lines in A–D). Osseous condensations are stained red and cartilage is stained blue. In chicken and gecko the palatine bones ossify adjacent to but not within the palatine processes (arrows) (A’,B’). Key: c, choana; e, eye; mc, in, internal nares; Meckel’s cartilage; nc, nasal cavity; p, palate; pb, palatine bone; pp, palatine process; ppmx, palatine process of maxillary bone; pv, palatal valve; tc, trabeculi cranii. Scale bars: A = 5.0 mm, B,C,F = 2 mm, A’,D’ = 1.0 mm, B’,C’ = 500 μm.