Abstract

Objective

Deciding among medical treatment options is a pivotal event following cancer diagnosis, a task that can be particularly daunting for individuals uncomfortable with communication in a medical context. Few studies have explored the surgical decision-making process and associated outcomes among Latinas. We propose a model to elucidate pathways though which acculturation (indicated by language use) and reports of communication effectiveness specific to medical decision making contribute to decisional outcomes (i.e., congruency between preferred and actual involvement in decision making, treatment satisfaction) and quality of life among Latinas and non-Latina White women with breast cancer.

Methods

Latinas (N = 326) and non-Latina Whites (N = 168) completed measures six months after breast cancer diagnosis, and quality of life was assessed 18 months after diagnosis. Structural equation modeling was used to examine relationships between language use, communication effectiveness, and outcomes.

Results

Among Latinas, 63% reported congruency in decision making, whereas 76% of non-Latina Whites reported congruency. In Latinas, greater use of English was related to better reported communication effectiveness. Effectiveness in communication was not related to congruency in decision making, but several indicators of effectiveness in communication were related to greater treatment satisfaction, as was greater congruency in decision making. Greater treatment satisfaction predicted more favorable quality of life. The final model fit the data well only for Latinas. Differences in quality of life and effectiveness in communication were observed between racial/ethnic groups.

Conclusions

Findings underscore the importance of developing targeted interventions for physicians and Latinas with breast cancer to enhance communication in decision making.

Keywords: breast cancer, medical communication, decision making, Latina, quality of life

Introduction

The equivalent survival rates conferred by mastectomy and breast-conserving surgery in early-stage breast cancer not only provide more surgical options but also contribute to women's greater participation in treatment decision-making. Understanding how ethnic minority patients manage treatment decisions for breast cancer is important in that they may face additional stressors related to language barriers as well as distinct cultural expectations and preferences regarding patient-physician interactions (Maly, Umezawa, Ratliff, & Leake, 2006). Although the Latino population constitutes the largest and fastest growing ethnic minority group in the U.S. (Ennis, Rios-Vargas, & Albert, 2011), their experience with surgical treatment decision making, particularly for individuals of lower socioeconomic status and acculturation, has not been comprehensively explored (Hamilton et al., 2009).

The few studies that focus on Latinas have demonstrated that, compared to non-Latina Whites, Latinas desire more information about treatment (Janz, Mujahid, Hawley, Griggs, Hamilton & Katz, 2008), but receive less information (Maly, Leake, & Silliman, 2003). Compared to Whites, Latinas are less likely to participate in the treatment decision-making process and have higher treatment decision regret (Hawley et al., 2008; Maly, Umezawa, Ratliff, & Leake, 2006), greater dissatisfaction with treatment (Hawley et al., 2008; Katz et al., 2005), and poorer quality of life after treatment (Carver, Smith, Petronis & Antoni, 2006; Janz et al., 2009; Maly, Stein, Umezawa, Leake, & Anglin 2008). Patient-physician communication among Latinos has been identified as an important aspect of the medical treatment context warranting research and intervention (Ramirez et al., 2005).

Understanding patient-physician communication during the surgical treatment decision-making process and its association with decisional outcomes (i.e., treatment satisfaction, congruency between desired and actual level of decision-making involvement) and quality of life may inform the development of interventions in this growing and understudied population. Accordingly, the primary aim of this study was to develop a model which relates patient-physician communication during the medical decision-making process to decisional outcomes and quality of life in a sample of low-income Latinas and White women.

Potential ethnic disparities in the decision-making process may be explained by several factors. Acculturation has been shown to be an important factor in cancer screening (De Alba, Sweningson, Chandy, Hubbell, 2004; Warren, Londono, Wessel, & Warren, 2006) and is likely to be important during breast cancer decision making (Hawley et al., 2008) in that Latinas, particularly less-acculturated Latinas, may experience barriers related to language proficiency. Within Latinas, greater acculturation is related to greater involvement in decision making (Hawley et al., 2009). One of the most widely cited multidimensional conceptualizations of acculturation is Berry's (2005) acculturation framework. This framework posits that acculturation is the “dual process of cultural and psychological change that takes place as a result of contact between two or more cultural groups and their individual members” (p. 698, Berry, 2005). Although acculturation encompasses various change processes, ranging from language use to cultural attitudes, we elected to focus on language use as a proxy for acculturation because it is highly relevant in the patient-physician communication context. Furthermore, language use is correlated with other measures of acculturation such as nativity and culture, and it accounts for most of the variance among acculturation scores (Hunt, Schneider, & Comer, 2004; Lara, Gamboa, Kahramanian, Morales, & Bautista, 2005). Moreover, language is considered one of the most important components of ethnic identity and has been commonly and widely assessed across acculturation instruments (Laroche, Kim, Hui, & Tomiuk, 1998; Phinney, 1990).

In addition to facing language barriers, Latinas may interact with health care providers who possess limited understanding of Latino culture. Furthermore, physicians may provide more psychosocial support and engage in relationship building with patients who are more educated, affluent, and White versus ethnic minority (Siminoff, Graham, & Gordon, 2006). Perceptions of racism and language barriers may also limit the establishment of rapport and ultimately the quality of patient-physician interactions (Schouten & Meeuwesen, 2006). Variations in communication styles between collectivistic and individualistic cultures may also influence levels of assertiveness in communication, such that more acculturated women present in a more assertive manner and consequently their physicians may be more inclined to query their preferences about treatment options (Schouten & Meeuwesen, 2006). Thus, it stands to reason that greater acculturation as measured by language use may be associated with greater effectiveness in patient-physician communication (Thind & Maly, 2006). The literature suggests that the decision-making process may be limited by low perceived efficacy in patient-physician communication and lack of information exchange in the form of specific treatment information provided, physician inquiry regarding the patient's concerns and preferences, and physician responsiveness to the patient.

Models of medical communication underscore the significance of preexisting individual factors (e.g., sociodemographics, communication competence) in conjunction with decision-making environmental factors as key to enhancing the decision-making process and the actual decision outcome (Feldman-Stewart, Brundage, & Tishelman, 2005; Siminoff & Step, 2005). Models of communication have also delineated pathways through which patient-physician communication can influence health-related outcomes. The relational communication involvement model, for example, postulates that oncologist communication may shape health-related outcomes via patient involvement during the decision-making process (Step, Rose, Albert, Cheruvu, & Siminoff, 2009). Both empirical findings and conceptual models indicate that attributes patients bring to the decision-making context, physician attributes, and qualities of the patient–physician interaction, influence decisional and health-related outcomes (e.g., Arora, 2003; Feldman-Stewart, Brundage, & Tishelman, 2005; Hawley et al., 2008; Siminoff & Step, 2005).

Several outcomes of the decision-making process are important, including congruence between patients’ preferred and actual involvement in the process, treatment satisfaction, and, ultimately, quality of life and health. The scope of preferred involvement ranges from delegating the decision to the physician or family members to desiring complete involvement in the process (Bruera, Willey, Palmer, & Rosales, 2002; Degner, Sloan, & Venkatesh, 1997; Janz, Wren, Copeland, Lowert, Goldfarb, & Wilkins, 2004). In a recent review of preferred and actual involvement in decision making among the general cancer population, the majority of studies found that patients wanted more involvement than they experienced (Tariman, Berry, Cochrane, Doorenbos, & Schepp, 2010). Among samples of predominantly White patients, better perceived patient-physician communication and patient satisfaction have been associated with increased involvement in decision making (Janz et al., 2004), favorable quality of life (Kerr, Engel, Schlesinger-Raab, Sauer, & Holzel, 2003; Ong, Visser, Lammes & de Haes, 2000) and adherence to medical regimens (DiMatteo, 2003). Additionally, findings from the general breast cancer literature reveal that patients who participate at their desired level report greater satisfaction with treatment and the decision-making process in addition to fewer depressive symptoms across time (Keating, Guadagnoli, Landrum, Borbas, & Weeks, 2002; Lantz et al., 2005; Vogel, Leonhart, Helmes et al., 2009). Research has yet to address congruency between preferred and actual level of involvement in relation to quality of life among Latinas.

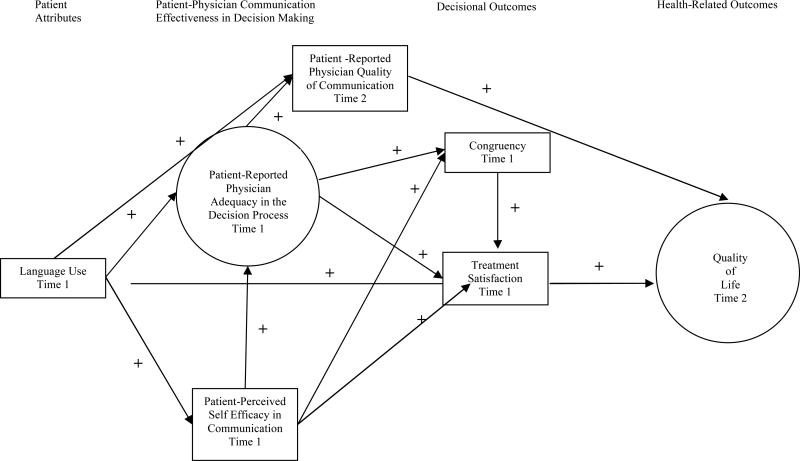

In line with previous research and conceptual models of patient-physician communication, we posit a model of the decision making composed of four major components: 1) patient attributes brought to the decision making interaction (i.e., English language use as a proxy for acculturation); 2) factors comprising effective patient-physician communication in decision making (patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision-making process, patient-perceived self-efficacy in communication); 3) decisional outcomes (i.e., congruency between preferred and actual levels of decision making, satisfaction with treatment; and 4) quality of life (Figure 1).1 Specific hypothesized pathways are illustrated in Figure 1. Greater use of English was expected to be related to more positive aspects patient-physician communication effectiveness in decision making (hypothesized to be linked). Patient-reported physician quality of communication was hypothesized to be linked to quality of life. Congruency in decision making was hypothesized to be linked to greater treatment satisfaction, which in turn was hypothesized to predict greater quality of life at 18 months after diagnosis, in light of the finding that higher satisfaction with care is associated with better quality of life after treatment for breast and prostate cancer (Davis, Kinman, Thomas, & Bailey, 2008; Hart, Latini, Cowan, Carroll, & CaPSURE Investigators, 2008). All indirect effects were hypothesized to be significant. A secondary goal was to compare models across racial/ethnic groups.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of patient-physician communication in decision making and association to quality of life. Paths where a positive association was predicted are represented with a plus sign (+).

Method

Participants

Participants were newly diagnosed women with breast cancer enrolled in the Medi-Cal (California's Medicaid) Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program (BCCTP). BCCTP funds treatment for uninsured, underinsured, and low-income women. Data were collected at 6 months (Time 1) and 18 months (Time 2) after diagnosis. Written invitations to participate in a 1-hour telephone survey in either English or Spanish were mailed to 1869 women, of whom 60 refused further contact. Of 1709 potential participants, 1036 eligible women agreed to participate, with 921 women completing the Time 1 survey and 790 women completing surveys at both points. Chen et al. (2008) provide a detailed description of methodology and recruitment (see also Christie, Meyerowitz, & Maly, 2010). Women were excluded if they did not self-identify as White or Latina, had not completed surgery by the first assessment, or were diagnosed with Stage 0 or IV as they likely had a different decision-making experience than women diagnosed with early stage cancer (i.e., Stages I- III). The current sample consists of 326 Latina women and 168 Whites. Compared with Time 1 survey responders, Time 2 nonresponders did not significantly differ on demographic variables, medical and cancer-related variables, and effectiveness in communication variables (all ps >.05). Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish; 83% of Latinas were interviewed in Spanish and 100% of Whites were interviewed in English.

Physicians

The majority of Latina and White participants reported that their surgeon was male (80%) and 81% of Latinas reported that their surgeon was of a different racial/ethnic background. Sixty-three percent of Latinas reported that their surgeon did not speak their language.

Measures

Questionnaires were translated into Spanish and then back translated into English and the two versions reconciled between translators.

Language use

Latina acculturation was measured at Time 1 with the Language Use subscale of the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (Marin, Sabogal, VanOss Marin, Otero-Sabogal & Perez-Stable, 1987). The 5 items assess what language the participant spoke as a child, with friends, and at home, with a higher total score (range = 5 – 25) indicating more use of English than another language. The subscale has reliability and validity coefficients similar to the full scale and may be used in its place (Marin et al., 1987). Internal consistency reliability was high (α = .93) in the present sample. White women did not complete the scale.

Patient-physician communication effectiveness in decision making

. Administered at Time 1, the Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions Questionnaire (PEPPI) contains 5 items that describe patients’ confidence in their ability to communicate with physicians and obtain needed attention to chief medical concerns (Maly, Frank, Marshall, DiMatteo, & Reuben, 1998). High scores (range = 0 – 50) reflect higher perceived self-efficacy in communication. The internal consistency reliability coefficients were ≥ .89 for Latinas and Whites.

Patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision-making process was measured with items assessing physician inquiry, time and information provision, and interactive information giving. To assess physician inquiry into treatment preferences at Time 1, patients were asked “How much did your breast cancer doctor ask you for your input or opinion about which treatment you preferred?” Responses were on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “a great deal.” The item on inquiry demonstrates convergent validity with other measures of patient-physician communication (Maly et al., 2008). To assess patient reported time and information provision regarding their treatment, patients were asked “Would you have liked more time or information to help you decide about the treatment?” Responses were on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “a great deal.” Scores were reverse coded such that higher scores reflected sufficient receipt of time and information. Time and information provision demonstrates convergent validity with other measures of patient-physician communication and predictive validity with medical outcomes (Heisler et al., 2002; Kaplan, Gandek, Greenfield, Rogers & Ware, 1995). At Time 1, interactive information giving was measured with a published index (Maly, Leake, & Silliman, 2003) which asked how many of 15 breast cancer-related topics that any of the participants’ physicians had discussed with them. The measure forms a unidimensional scale (range = 0- 15) (Maly, Leake, & Silliman, 2003) and demonstrates convergent validity with other measures of patient-physician communication. The breast cancer surgeon was the most frequently mentioned as the physician discussant in all 15 topics. Scale reliability coefficients were ≥.84 for Latinas and Whites.

Assessing patient-reported surgeon communication skills, the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey (Hargraves, Hays, & Cleary, 2003), administered at Time 2, evaluates the surgeon-patient interaction with a total score on four questions (e.g., “How often did he/she listen carefully to you?”). Responses were on a 4-point Likert scale: never, sometimes, usually, and often. Scale reliability coefficients were ≥ .89 for Latinas and Whites.

Decisional outcomes

At Time 1, congruency between preferred and actual decision-making involvement was coded as the match between two questions: “Would you have preferred that the doctor make the decision for you?” and “Who would you say made the final decision about the kind of treatment you should have for your breast cancer?” Only participants (98%) who responded with self or a physician as the final decision maker were included in analyses. Congruency was coded as a binary variable indicating a match or no match between the two questions.

A single item at Time 1 asked overall how satisfied women were with their breast cancer care. Responses ranged from 1-5, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

Sociodemographic and cancer-related variables.

Stage of breast cancer, education, age, and comorbidities are factors that can be related to quality of life outcomes. Stage of cancer was confirmed by chart review; education and age were provided by self-report. Assessed at Time 1, comorbidities were assessed by self-report using the Katz adaptation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (Katz, Chang, Sangha, Fossel, & Bates, 1996).

Quality of life

. As a multidimensional construct, quality of life was assessed with three measures at Time 2. The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (MOS SF-36) is a 36-item self-report measure of quality of life, organized into eight dimensions (e.g., physical functioning, bodily pain, social functioning), which can be combined to form Mental Component Summary and Physical Component Summary scores (Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1994). Scores are standardized, ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. Internal consistency coefficients were ≥ .88 for Latinas and Whites. The Breast Cancer Prevention Trial Symptom Checklist (BCPT), completed at Time 2, assesses eight domains of symptoms associated with breast cancer treatment (e.g., hot flashes, cognitive problems, weight problems; Stanton, Bernaards, & Ganz, 2005). Women rated the extent they were bothered by each symptom on a scale ranging from 0-4; the total score was used. Internal consistency coefficients were ≥ .83 for Latinas and Whites. Breast cancer-specific emotional health was assessed with four items, including worrying about the breast cancer recurring or worrying about the family's ability to manage if the participant gets sicker (Silliman, Dukes, Sullivan, & Kaplan, 1998). The scale demonstrates convergent validity with important quality of life outcomes (Maly et al., 2008). Responses ranged from 1-4, with higher scores indicating greater worry. Internal consistency reliability coefficients were ≥ .82 for Latinas and Whites. The breast cancer-specific emotional health and breast cancer symptoms scales were reverse coded such that higher scores indicated more favorable quality of life.

Data Analysis

Multivariate normality was violated so the models were estimated with ML and evaluated with the Robust S-B χ2. Initial confirmatory factor analyses were performed with each latent construct. This analysis tested the measurement model and examined associations among the latent and measured variables. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to examine the relations among language use, communication in decision making, decisional outcomes (i.e., treatment satisfaction and congruency in decision making), and quality of life. Models were tested using maximum likelihood estimation in EQS (Version 6.1). To evaluate goodness of model fit, multiple fit indices were computed: Robust S-B χ2, robust root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), robust comparative fit index (CFI), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Lagrange Multiplier tests and Wald tests were examined to see if any additional paths should be included or excluded, if theoretically plausible (Chou & Bentler, 1990). In addition, the models for the two racial/ethnic groups were compared with multiple group analyses, without the inclusion of language use in the model as Whites were not administered the language use scale.

Results

Table 1 displays sociodemographic information and cancer-related descriptive data, and Table 2 displays descriptive statistics on the decision-making and dependent variables. Eighty-eight percent of Latinas reported they were born in Mexico, Central or South America, and 11% reported being born in the United States.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Cancer-Related Characteristics

| Variable Value | Latinas | Non-Latina Whites |

|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 50.03 (9.37) | 53.80 (9.41) |

| Range | 25-85 | 27-82 |

| Education, N (%) | ||

| ≤ High School | 263 (80.67%) | 61 (36.3%) |

| >High School | 62 (19%) | 107 (63.7%) |

| Income, N (%) | ||

| Less than $10,000 | 106 (32.5%) | 50 (30.5%) |

| $10,000- <$20,000 | 74(22.7%) | 69 (42.1%) |

| $20,000- <$30,000 | 96 (29.5%) | 31 (18.9%) |

| Greater than $30,000 | 50 (14.7%) | 14 (8.5%) |

| Comorbidity, N (%) | ||

| None | 243(74.5%) | 108 (64.3%) |

| Any | 83(25.5%) | 60 (35.7%) |

| Stage of Diagnosis, N (%) | ||

| I | 94 (28.8%) | 63 (37.5%) |

| II | 166(50.9%) | 66 (39.3%) |

| III | 66(20.3%) | 39 (23.2%) |

| Treatment Type, N (%) | ||

| Lumpectomy | 174(53.4%) | 94 (56%) |

| Mastectomy | 149(45.7%) | 69 (41%) |

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Factor Loadings in the Confirmatory Factor Analysis

| Variable | Latinas M (SD) or Percent Distribution | Whites M(SD) or Percent Distribution | p-value | Latina Standardized and Unstandardized Factor Loadings* | White Standardized and Unstandardized Factor Loadings* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | B | β | B | ||||

| Language Use | 7.53(4.50) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Patient Perceived Self-Efficacv in Communication | 35.67(13.32) | 41.15(9.41) | <.001 | - | - | - | - |

| Patient-Reported Physician Adequacy in the Decision Process | |||||||

| Interactive Information Giving | 9.33 (2.79) | 11.32(2.69) | <.001 | .60 | 1.00 | .61 | 1.00 |

| Time/Information Provision | 13.27 (3.20) | 14.57(2.74) | <.001 | .31 | .21 | .58 | .40 |

| Physician Inquiry into Preferences | 2.82 (1.10) | 3.09(1.11) | <.05 | .71 | .47 | .57 | .43 |

| Patient-Reported Physician Quality of Communication | 1.93(1.15) | 2.33(1.07) | <.001 | - | - | - | - |

| Congruency in Decision Making Involvement dncongruent/Congruenf) | 37.12/62.88 | 23.80/76.20 | <.05 | - | - | - | - |

| Treatment Satisfaction | 4.85 (0.40) | 4.69(0.62) | <.05 | - | - | - | - |

| Quality of Life | |||||||

| Breast Cancer Symptoms | 52.17 (9.98) | 52.40(10.55) | .81 | .88 | 1.00 | .55 | 1.00 |

| Breast Cancer Emotional Health | 10.51 (3.36) | 11.98(3.22) | <.001 | .31 | .12 | .65 | .36 |

| SF-36 Physical Health | 43.97 (10.01) | 43.26(11.80) | .52 | .64 | .73 | .44 | .90 |

| SF-36 Mental Health | 47.22 (12.10) | 45.40(13.03) | .13 | .48 | .67 | .84 | 1.90 |

All factor loadings p < .05.

Comparisons between Latinas and Whites revealed that Latinas revealed discrepancies in several key measures. Latinas reported worse communication relative to their White counterparts. Latinas also reported poorer breast cancer emotional health than Whites. However, Latinas reported higher treatment satisfaction than Whites.

Preliminary analyses

Control variables including stage of cancer, education, age, and having one or more comorbid conditions were examined for inclusion in the hypothesized model. Having a comorbid condition was significantly related to the quality of life outcomes among Latinas and Whites and therefore was included in analyses (Table 3). The most common comorbid conditions were rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes. Other potential control variables were not included in analyses as they were not significantly related to quality of life, congruency in decision making, or treatment satisfaction for either Latinas or Whites (all ps > .05). Stage of cancer was modestly correlated with physician inquiry into treatment preferences for Latinas, but was not correlated with any other indicators of the communication effectiveness variable and was not included in analyses.

Table 3.

Zero-Order Correlations for All Measured Variables in the Model. Latinas below Diagonal, non-Latina Whites above Diagonal.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Language Use | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 2. | Patient Self- Efficacy | .17* | .21** | .29** | .20* | .30** | .10 | .22** | .03 | −.08 | .10 | −.07 | .04 | |

| 3. | Information Giving | .37*** | .40*** | - | .29** | .35*** | .35** | −.06 | .40*** | .06 | .03 | .10 | .11 | .04 |

| 4. | Physician Comm. Skills | .18* | .28** | 32*** | .27** | .24** | .08 | .31** | .09 | .08 | .12 | .09 | .01 | |

| 5. | Physician Inquiry | .10 | .33*** | 45*** | .28*** | - | .35*** | .07 | .29** | .11 | .07 | .05 | .15 | .03 |

| 6. | Time/ Information Provision | .05 | .08 | .20** | .12 | .25** | .03 | .31** | .09 | .22** | .10 | .19** | −.02 | |

| 7. | Congruency | .05 | −.03 | .05 | .12 | .02. | .10 | - | −.07 | −.03 | −.01 | −.09 | .02 | .04 |

| 8. | Treatment Satisfaction | −.09 | .16* | .22** | .20** | .16* | .15* | .18* | - | .06 | .12 | .19* | −.03 | .04 |

| 9. | Breast CA Concerns | −.06 | .05 | .06 | .06 | .08 | .03 | .07 | .24** | - | .35*** | .47*** | .53*** | −.21** |

| 10. | Breast CA Emotions | .10 | .10 | .07 | .12 | .04 | .12 | .08 | .12 | .30** | - | .54*** | .26** | − 13* |

| 11. | Mental Health | .01 | .13* | .10 | .19** | .03 | .02 | .10 | .14* | .45*** | .50*** | - | .25 | −.15 |

| 12. | Physical Health | −.09 | .11 | .06 | .01 | .10 | .03 | .02 | .16* | .58*** | .20** | .20** | - | −.40*** |

| 13. | Comorbid Condition | .08 | −.10 | -.06 | .05 | −.01 | .05 | −.03 | -.02 | −.22** | −.11 | −.15* | −.23** | - |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Confirmatory factor analyses

. For Latinas, fit indices for the CFA model testing the adequacy of the measurement model were good: Robust S-B χ2 (11, N = 326) = 8.41, p = .68, Robust CFI = 1.00, Robust RMSEA = .00, SRMR = .03. Similarly, for Whites, fit indices for the CFA were good: Robust S-B χ2 (11, N = 168) = 13.56, p = .26, Robust CFI = .99, Robust RMSEA = .04, SRMR = .04. Table 2 presents the factor loadings of the measured variables on their hypothesized latent variables in the CFA model, as well as the means and standard deviations or frequencies of all measured variables in the model. All measured variables hypothesized to be indicators of the latent variables had factors loadings that exceeded .30, and all were significant (p < .05).

Group Comparisons

The initial factor structures for the two racial/ethnic groups were compared with a test of factorial invariance. The Robust ΔS-B χ2 between the model with the factor loadings constrained to equality between the Latina and White groups and a nonconstrained model was 23.20 with a change in five degrees of freedom (p <.001). Thus, the factor structures were not comparable across groups; Lagrange Multiplier tests indicated that the factor loadings for information and time provision, breast cancer emotional health, and mental health contributed to the difference. Releasing these equality constraints improved the Robust SB χ2 difference between models to non-significance.

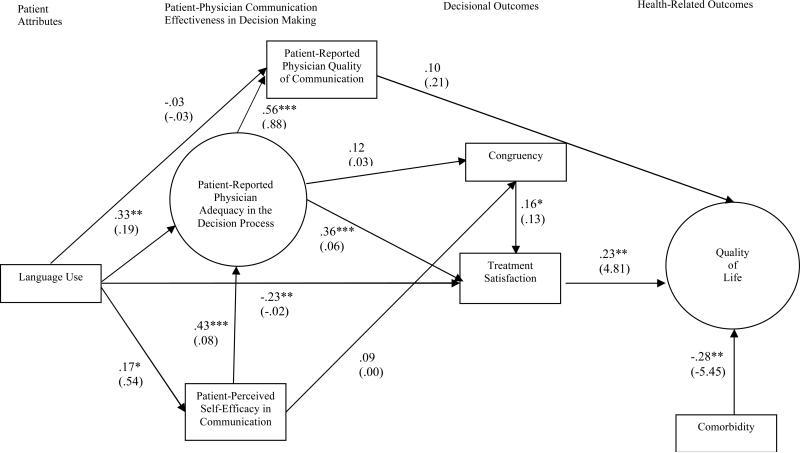

Structural equation model for Latinas

Mardia's normalized multivariate coefficient for the sample of Latinas (7.6) was elevated. The SEM model had a good fit for Latinas: Robust S-B χ2 (54, N= 326) = 67.87, p = .09, Robust CFI = .97, Robust RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .04. After removal of the non-significant path from patient perceived self-efficacy in communication to treatment satisfaction based on the Wald test, the final model Robust S-B χ2 (55, N= 326) = 68.05, p = .11, Robust CFI = .97, Robust RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .04 continued to demonstrate a good fit. In the final model, language use and patient perceived self-efficacy in communication explained 34.0% of the variance in patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process. Language use, congruency in decision-making, and patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process explained 16.0% of the variance in treatment satisfaction. Patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process explained 28.0% of the variance in patient-reported quality of physician communication. Treatment satisfaction, patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process and comorbid conditions explained 16.0% of the variance in quality of life. The indirect effect of language use on patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process was significant (standardized coefficient = .08, p<.05). The indirect effects of patient- perceived efficacy in communication and language use on patient-reported physician quality of communication were significant (standardized coefficients = .23, .21, respectively, ps < .05). The indirect effects of patient-perceived efficacy in communication and language use on treatment satisfaction were significant (standardized coefficients = .15, .15, respectively, ps < .05). The indirect effects of congruency in decision making, patient-perceived efficacy in communication, and patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process on quality of life were significant (standardized coefficients = .04, .06, .15, respectively, ps < .05). Neither the indirect effect of patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process on satisfaction nor the indirect effect of language use on quality of life was significant (ps > .05). No indirect effects on congruency were significant (ps > .05.)

Structural Equation Model for non-Latina Whites

The hypothesized model for Latinas was replicated among the White sample, without the inclusion of language use in the model. The initial model did not have a good fit: Robust S-B χ2 (47, N= 168) = 66.00, p = .03, Robust CFI = .92, Robust RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Lagrange Multiplier and Wald tests did not indicate reasonable path modifications that would improve the model fit. Because the structural model was not a good fit for White women, we elected not to run tests of invariance at the structural level between Latinas and Whites.

Discussion

This study is among the first to examine pathways though which language use and perceptions of communication effectiveness specific to a medical decision-making context contribute to decisional outcomes and quality of life in Latinas with breast cancer. Consistent with hypotheses, greater use of English was associated with greater patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process and greater patient self-efficacy in communication. Greater patient-perceived efficacy in communication was associated with greater patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process. In turn, greater patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process was related to greater treatment satisfaction, as was congruency in decision making. Greater patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process predicted greater patient-reported physician quality of communication at 18 months. Higher treatment satisfaction at six months after diagnosis predicted more favorable quality of life at 18 months. Significant indirect effects suggest that language use, patient-perceived efficacy in communication, and patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process contribute to outcomes in the model.

These findings underscore the important role that language plays in contributing to effective patient-physician communication during the medical decision-making process. The process of making a medical decision can be daunting, especially for women unfamiliar with the dominant culture of the medical system and from lower socioeconomic environments, who may have limited resources in place. In the current study, level of acculturation was measured by predominant language use; Latinas with greater command of English are likely to experience fewer barriers to medical communication in the United States and may feel more comfortable being assertive in communicating preferences and concerns with physicians (Schouten & Meeuwesen, 2006).

In light of the established findings of greater treatment dissatisfaction and poorer quality of life demonstrated by Latinas with breast cancer (Janz et al., 2009; Yanez, Thompson, & Stanton, 2011), the current findings also suggest that enhancing patient-physician communication for this group is of particular importance. Among Latinas, a diagnosis of breast cancer might be especially disruptive in light of culturally-specific causal attributions about cancer, including the belief that cancer represents punishment as well as fatalistic beliefs that cancer is equated with a death sentence (Buki, Garces, Hinestrosa, Kogan Carillo, French, 2008; Espinosa de los Monteros & Gallo, 2010; Ramirez, Suarez, Laufman, Barroso, Chalela, 2000). Effective patient-physician communication can be a means to help Latinas establish more adaptive and realistic beliefs about their prognosis and ultimately enhance their medical experience.

Findings that were counter to hypothesis also deserve attention. Greater use of English among Latinas was associated with lower treatment satisfaction. Perhaps low-income Latinas who use more English had more access to informational resources, were more likely to compare the medical care they received to an optimal treatment scenario, or had higher expectations for their medical care, contributing to lower satisfaction.

Also contrary to hypothesis, neither patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process nor patient-perceived communication self-efficacy was significantly related to congruency. One potential explanation is that Latinas may have desired to be the final treatment decision maker but elected to defer the decision to their physicians out of respect for authority figures. Respect for authority figures, termed respecto in Spanish, is an important characteristic of Hispanic cultures. Patients taking the lead in conversation or making the final treatment decision may be viewed by Latinos, as arrogant (Sheppard et al., 2008). Cultural expectations may have prevented women from taking the lead in making the decision despite having experienced an effective patient-physician communication process, thus weakening the link between communication effectiveness and congruence. Among Latinas and Whites, external factors also may contribute to the lack of association. It is possible, for example, that family or friends who were present during the consultation encouraged the patient to change her desired level of participation. Such external influences are not captured in the current model. Collection of data regarding women's explanations for or other contributors (e.g., agreeableness) to incongruence in decision making would provide a richer explanation of the relevance of this variable for Latinas and other women. It is also worth noting that the present study employed one approach to establishing congruency in decision making and other approaches for establishing congruency in decision making should be investigated in future research. Also worth noting is that although higher patient self-efficacy in communication was not directly related to congruency or treatment satisfaction, it did have a significant indirect effect on satisfaction. Similarly, although language use was not related to patient-reported physician quality of communication, it did have a significant indirect effect on patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process.

Patient-reported physician quality of communication was not significantly related to better quality of life, suggesting that among Latinas it is the more practical aspects of the physician-initiated communication reflected in the patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process construct that more strongly relate to decisional and health outcomes. One interpretation of this finding is that among Latinas, specifically those who have little to no command of the English language, the practical aspects of communication in decision making are more strongly related to outcomes than the quality or value placed on the communication.

Bivariate analyses between Latinas and Whites revealed several notable group differences (Table 2). Compared to Latinas, Whites reported significantly better efficacy in communication, greater patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process, greater patient-reported physician quality in communication, greater treatment satisfaction, and greater congruency in decision-making. Whites reported significantly better breast cancer emotional health, a finding which is consistent with the literature on quality of life disparities in breast cancer (Yanez et al., 2011). These findings underscore the need for interventions to improve Latinas’ communication in decision-making. Tests of invariance for factor loadings across Latinas and non-Latinas revealed significant differences on factor loadings for the patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process and quality of life. These results suggest that ethnicity may moderate the structure of patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process and quality of life for Latinas and Whites. Time and information provision was less strongly related to patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision-process for Latinas than for Whites. For Latinas, quality life was more strongly associated with breast cancer symptoms and physical health, whereas for Whites quality of life was more strongly associated with emotional health and mental health. Fit indices for the structural equation model revealed that the model was not a good fit for White women. This finding is not surprising given that the hypothesized model is a conceptually driven model developed for Latina women with the language use variable central to the model and the specific aim of testing direct and indirect paths between language use, communication in decision making, and outcome variables.

Results suggest that better patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process appears to contribute directly to high treatment satisfaction. Women's communication self-efficacy appears important to extent that it facilitates better physician communication. However, reverse causality is plausible. Research also is necessary to examine additional contributors to treatment satisfaction and quality of life. For example, one possibility is that women who reported greater overall satisfaction with treatment also experienced better quality of care (e.g., comprehensive hospital, more knowledgeable treatment team), which increased quality of life.

Findings require interpretation in light of additional study limitations. Findings are based on patient retrospective self-report and therefore are subject to recall and response biases; however, patients with breast cancer can accurately report details of their treatment (Liu, Diamant, Thind, Maly, 2010). Another limitation is the use of language as a proxy for acculturation; other potentially influential aspects of the acculturation process were not captured in the current model. For example, inclusion of indicators of acculturation such as women's perspectives on social roles may provide a richer measurement of acculturation, as views on social roles are likely inform communication processes. Also worth noting is that the current model employed a single-item measure of treatment satisfaction. Single-item measures must be interpreted with caution as they may have low reliability. However, if the construct being measured is unambiguous and narrow in scope, single-item measurement may suffice (Gardner, Cummings, Randall, Dunham, & Pierce, 1998). Participants were recruited from California, and the majoritywere of Mexican origin (California Health Interview Survey, 2005). Mexicans are the least likely of Latino populations living in the United States to have graduated from high school and are more likely to be living below the poverty level (compared to Cubans) (Howe et al., 2006). Although additional Latino groups warrant study, Latinas of Mexican heritage are an important group to target for investigation and evidence-based intervention.

Findings support the importance of interventions targeted at enhancing patient-reported physician adequacy in the decision process and women's self-efficacy for communicating with their physicians. Such approaches may consist of modeling question asking and helping women to prepare questions prior to their medical consultation (Greenfield, Kaplan, Ware, Yano & Frank, 1988). Interventions are needed to facilitate expression of patients’ priorities and concerns in a manner which is concordant with their culture but which also promotes comfort with expression. The goal of such interventions is to provide women with the maximum opportunity to have their concerns addressed and their treatment preferences acknowledged. Although very limited, research on interventions to enhance decision-making skills suggests that Latinas prefer help with asking questions and can benefit from resources such as Latina peer role models (Shepard et al., 2008); additional studies are needed to determine the most effective ways to implement culturally sensitive interventions to enhance communication.

Current findings also highlight the important role physicians play in the decision-making process. Some physicians ignore the psychosocial aspects of illness and the need to engage patients explicitly in a discussion of patients’ decisional preferences (Dowsett, Saul, Butow, Dunn, Boyer, Findlow et al., 2000). Research demonstrates that Latinas are likely to benefit when their physician elicits patient preferences, provides information tailored to their diagnosis, and asks open-ended questions (see Lee, Back Block, & Stewart, 2002 for a review on medical communication). Although Latinas, specifically Spanish-speaking Latinas, are less likely to make the final treatment decision compared to their White counterparts (Hawley et al 2009, Maly et al., 2006), health care professionals should not equate lower desired involvement in decision making with a desire for less cancer-related information or attention to their needs. Latinas may also benefit from having physicians elicit their preferences for involvement in decision making, which may establish rapport and invite a collaborative decision-making process. Continued research in the areas of patient-physician communication and decision making can inform targeted and tailored interventions to improve the breast cancer experience of Latinas.

Figure 2.

Final structural equation model of correlates of patient-physician communication in decision making and association to quality of life for Latinas. All estimated parameters are standardized with unstandardized coefficients in parentheses. The circles designate latent variables; the squares represent measured variables. *p < .05. **p < .01. *** p < .001.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the American Cancer Society (# TURSG-02-081); California Breast Cancer Research Program (# 7PB-0070); National Cancer Institute (# 1R01CA119197-01A1). This research was also made possible by the University of California Los Angeles Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center Dissertation Fellowship awarded to Dr. Betina Yanez. We thank the reviewers for their helpful comments and Sarah Ormseth for her assistance with portions of the data analyses.

Footnotes

The hypothesized model is a revised model based on a reviewer's recommendation to separate indicators of effective communication. In the original model, all factors comprising effective patient-physician communication in decision making were combined into one latent variable. Although both models fit the data well, compared to the original model, the revised model was deemed more informative and is presented in the current paper.

Contributor Information

Betina Yanez, Institute for Healthcare Studies, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University

Annette L. Stanton, Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles

Rose C. Maly, Department of Family Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles

References

- Arora NK. Interacting with cancer patients: The significance of physicians’ communication behavior. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:791–806. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00449-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2005;29:697–712. [Google Scholar]

- Bruera E, Willey JS, Palmer JL, Rosales M. Treatment decisions for breast carcinoma: patient preferences and physician perceptions. Cancer. 2002;94:2076–2080. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buki LP, Garces DM, Hinestrosa M, Kogan L, Carrillo IY, French B. Latina breast cancer survivors’ lived experiences: Diagnosis, treatment, and beyond. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:163–167. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Health Interview Survey California Health Interview Survey 2005. 2005 Retrieved January 12, 2010, from http://www.chis.ucla.edu.

- Carver CS, Smith RG, Petronis VM, Antoni MH. Quality of life among long-term survivors of breast cancer: Different types of antecedents predict different classes of outcomes. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:749–758. doi: 10.1002/pon.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, Diamant AL, Thind A, Maly RC. Determinants of breast cancer knowledge among newly diagnosed, low-income, medically underserved women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:1153–1161. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CP, Bentler PM. Model modification in covariance structure modeling: A comparison among Likelihood Ratio, Lagrange Multiplier, and Wald tests. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:115–126. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2501_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie KM, Meyerowitz BE, Maly RC. Depression and sexual adjustment following breast cancer in low-income Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women. Psycho-oncology. 2010;19:1069–1077. doi: 10.1002/pon.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies NJ, Kinman G, Thomas RJ, Bailey T. Information satisfaction in breast and prostate cancer patients: Implications for quality of life. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17:1048–1052. doi: 10.1002/pon.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Alba I, Sweningson JM, Chandy C, Hubbell FA. Impact of English language proficiency on receipt of pap smears among Hispanics. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19:967–970. doi: 10.1007/s11606-004-0009-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The Control Preferences Scale. The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 1997;29:21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo RM. Future directions in research on consumer-provider communication and adherence to cancer prevention and treatment. Patient Education and Counseling. 2003;50:23–26. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett SM, Saul JL, Butow PN, Dunn SM, Boyer MJ, Findlow R, Dunsmore J. Communication styles in the cancer consultation: preferences for a patient-centred approach. Psycho-Oncology. 2000;9:147–156. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(200003/04)9:2<147::aid-pon443>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger-Raab A, Eckel R, Sauer H, Hölzel D. Predictors of quality of life of breast cancer patients. Acta Oncologica. 2003;42:710–718. doi: 10.1080/02841860310017658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Rios-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic Population: 2010 Census Briefs. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf.

- Espinosa de los Monteros K, Gallo LC. The relevance of fatalism in the study of Latinas’ Cancer Screening Behavior: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9119-4. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9119-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD, Tishelman C. A conceptual framework for patient-professional communication: an application to the cancer context. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14:801–809. doi: 10.1002/pon.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DG, Cummings LL, Dunham RB, Pierce JL. Single-item versus multiple-item measurement scales: An empirical comparison. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1998;58:898–915. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Jr., Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1988;3:448–457. doi: 10.1007/BF02595921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton AS, Hofer TP, Hawley ST, Morrell D, Leventhal M, Deapen D, Salem B, Katz SJ. Latinas and breast cancer outcomes: Population-based sampling, ethnic identity, and acculturation assessment. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2009;18:2022. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart SL, Latini DM, Cowan JE, Carroll PR. Fear of recurrence, treatment satisfaction, and quality of life after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2008;16:161–169. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargraves JL, Hays RD, Cleary PD. Psychometric properties of the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) 2.0 adult core survey. Health Services Research. 2003;38:1509–1527. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley ST, Janz NK, Hamilton A, Griggs JJ, Alderman AK, Mujahid M, Katz SJ. Latina patient perspectives about informed treatment decision making for breast cancer. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;73:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Graff JJ, Janz NK, Morrow M, Jagsi R, Salem B, Katz SJ. Decision involvement and receipt of mastectomy among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009;101:1337–1347. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler M, Bouknight RR, Hayward RA, Smith DM, Kerr EA. The relative importance of physician communication, participatory decision making, and patient understanding in diabetes self-management. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17:243–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe HL, Wu X, Ries LAG, Cokkinides V, Ahmed F, Jemal A, Miller B, Williams M, Ward E, Wingo PA, Edwards BK. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2003, featuring cancer among U.S. Hispanic/Latino populations. Cancer. 2006;107:1711–1742. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LM, Schneider S, Comer B. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on U.S. Hispanics. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;59:973–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Alderman A, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ. Racial/ethnic differences in quality of life after breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Survivorship. 2009;3:212–222. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0097-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ. Racial/ethnic differences in adequacy of information and support for women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:1058–1067. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Wren PA, Copeland LA, Lowery JC, Goldfarb SL, Wilkins EG. Patient-physician concordance: preferences, perceptions, and factors influencing the breast cancer surgical decision. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:3091–3098. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SH, Gandek B, Greenfield B, Rogers W, Ware JE. Patient and visit characteristics related to physicians’ participatory decision-making style. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Medical Care. 1995;33:1176–1187. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199512000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Medical Care. 1996;34:73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz SJ, Lantz PM, Paredes Y, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Liu L, Deapen D. Breast cancer treatment experiences of Latinas in Los Angeles County. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:2225–2230. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating NL, Guadagnoli E, Landrum MB, Borbas C, Weeks JC. Treatment decision making in early-stage breast cancer: Should surgeons match patients’ desired level of involvement? Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:1473–1479. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J, Engel J, Schlesinger-Raab L, Sauer H, Holzel D. Communication, quality of life, and age: Results of a 5-year prospective study in breast cancer patients. Annals of Oncology. 2003;14:421–427. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PM, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Schwartz K, Liu L, Lakhani I, Katz SJ. Satisfaction with surgery outcomes and the decision process in a population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Health Services Research. 2005;40:745–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the US: A Review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:367–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche M, Kim C, Hui M, Tomiuk MA. A test of a nonlinear relationship between linguistic acculturation and ethnic identification. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1998;29:418–433. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Back AL, Block SD, Stewart SK. Enhancing physician-patient communication. Hematology. 2002;2002:464. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2002.1.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Diamant AL, Thind A, Maly RC. Validity of self-reports of breast cancer treatment in low-income, medically underserved women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2010;119:745–751. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0447-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly RC, Leake B, Silliman RA. Health care disparities in older patients with breast carcinoma: informational support from physicians. Cancer. 2003;97:1517–1527. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly RC, Stein JA, Umezawa Y, Leake B, Anglin MD. Racial/ethnic differences in breast cancer outcomes among older patients: effects of physician communication and patient empowerment. Health Psychology. 2008;27:728–736. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly RC, Umezawa Y, Ratliff CT, Leake B. Racial/ethnic group differences in treatment decision-making and treatment received among older breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2006;106:957–965. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly RC, Frank JC, Marshall GN, Di Matteo MR, Reuben DB. Perceived efficacy in patient-physician interactions (PEPPI): Validation of an instrument in older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1998;46:889–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly RC, Umezawa Y, Ratliff CT, Leake B. Racial/ethnic group differences in treatment decision-making and treatment received among older breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2006;106:957–965. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:183. [Google Scholar]

- Ong LM, Visser MR, Lammes FB, de Haes JC. Doctor-patient communication and cancer patients’ quality of life and satisfaction. Patient Education and Counseling. 2000;41:145–156. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez AG, Gallion KJ, Suarez L, Giachello AL, Marti JR, Medrano MA, Trapido EJ. A national agenda for Latino cancer prevention and control. Cancer. 2005;103:2209 – 2215. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez AG, Suarez L, Laufman L, Barroso C, Chalela P. Hispanic women's breast and cervical cancer knowledge, attitudes, and screening behaviors. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2000;14:292–300. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.5.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revenson TA, Pranikoff JR. A contextual approach to treatment decision making among breast cancer survivors. Health Psychology. 2005;24:S93–S98. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.S93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In: von Eye A, Clogg CC, editors. Latent variables analysis: Applications for developmental research. Sage; Thousand Oakes, CA: 1994. pp. 399–419. [Google Scholar]

- Schouten BC, Meeuwesen L. Cultural differences in medical communication: A review of the literature. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;64:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard VB, Figueiredo M, Cañar J, Goodman M, Caicedo L, Kaufman A, Norling G, Mandelblatt J. Latina a Latina: Developing a breast cancer decision support intervention. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17:383–391. doi: 10.1002/pon.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman RA, Dukes KA, Sullivan LM, Kaplan SH. Breast cancer care in older women: Sources of information, social support, and emotional health outcomes. Cancer. 1998;83:706–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siminoff LA, Graham GC, Gordon NH. Cancer communication patterns and the influence of patient characteristics: disparities in information-giving and affective behaviors. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;62:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siminoff LA, Step MM. A communication model of shared decision making: accounting for cancer treatment decisions. Health Psychology. 2005;24:S99–S105. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Bernaards CA, Ganz PA. The BCPT symptom scales: A measure of physical symptoms for women diagnosed with or at risk for breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97:448. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Snider PR. Coping with a breast cancer diagnosis: A prospective study. Health Psychology. 1993;12:16–23. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Step MM, Rose JH, Albert JM, Cheruvu VK, Siminoff LA. Modeling patient-centered communication: oncologist relational communication and patient communication involvement in breast cancer adjuvant therapy decision-making. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;77:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariman JD, Berry DL, Cochrane B, Doorenbos A, Schepp K. Preferred and actual participation roles during health care decision making in persons with cancer: a systematic review. Annals of Oncology. 2010;21:1145–1151. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thind A, Maly R. The surgeon-patient interaction in older women with breast cancer: what are the determinants of a helpful discussion? Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2006;13:788–793. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel BA, Leonhart R, Helmes AW. Communication matters: The impact of communication and participation in decision making on breast cancer patients’ depression and quality of life. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;77:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. Physical and mental health summary scales: A user's manual. The Health Institute; Boston: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Warren AG, Londoño GE, Wessel LA, Warren RD. Breaking down barriers to breast and cervical cancer screening: a university-based prevention program for Latinas. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2006;17:512–521. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez B, Thompson EH, Stanton AL. Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2011;5:191–197. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0171-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]