Abstract

Although a robust literature documents a positive association between alcohol and intimate partner violence (IPV), there is limited temporal research on this relation. Moreover, the role of marijuana in influencing IPV has been mixed. Thus, the primary aim of the current study was to examine the temporal relationship between alcohol and marijuana use and dating violence perpetration. A secondary aim was to examine whether angry affect moderated the temporal relation between alcohol and marijuana use and IPV perpetration. Participants were college women who had consumed alcohol in the previous month and were in a dating relationship (N = 173). For up to 90 consecutive days, women completed daily surveys that assessed their alcohol use, marijuana use, angry affect (anger, hostility, and irritation), and violence perpetration (psychological and physical). On alcohol use days, marijuana use days, and with increases in angry affect, the odds of psychological aggression increased. Only alcohol use days and increases in angry affect increased the odds of physical aggression. Moreover, the main effects of alcohol and marijuana use on aggression were moderated by angry affect. Alcohol was positively associated with psychological and physical aggression when angry affect was high, but was unrelated to aggression when angry affect was low. Marijuana use was associated with psychological aggression when angry affect was high. Findings advance our understanding of the proximal effect of alcohol and marijuana use on dating violence, including the potential moderating effect of angry affect on this relation.

Keywords: alcohol, marijuana, dating violence, affect

Numerous theories highlight the role of substance use, particularly alcohol, in the perpetration of aggression broadly, and intimate partner violence (IPV) specifically (see review by Shorey, Stuart, & Cornelius, 2011). Indeed, a robust body of cross-sectional research and limited body of longitudinal research has supported these theories. For instance, a recent meta-analytic review (Foran & O’Leary, 2008) demonstrated small to medium effect sizes for the association between alcohol use/abuse and IPV among adults. Similarly, a review of cross-sectional studies on the relation between alcohol use and violence among college dating couples demonstrated robust relations between alcohol and IPV perpetration (Shorey et al., 2011). Unfortunately, cross-sectional studies on the relation between alcohol and IPV are difficult to interpret, as most theoretical models hypothesize that it is the acute effects of alcohol intoxication that increase the odds of IPV (e.g., Leonard, 1993), and only temporal studies on alcohol and IPV are able to demonstrate such relations.

Toward this end, only a handful of studies have attempted to uncover the temporal link between alcohol use and IPV. The scant body of research has demonstrated that IPV is more likely to occur on drinking days (any and heavy drinking days) relative to non-drinking days among urban adolescents seeking emergency department services (Rothman et al., 2012), women arrested for domestic violence (Stuart et al., in press), and college students (Moore, Elkins, McNulty, Kivisto, & Handsel, 2011; Parks, Hsieh, Bradizza, & Romosz, 2008). However, two of these studies used retrospective interviews to assess this relation (Rothman et al., 2012; Stuart et al., in press) and one study combined reports of victimization and perpetration and also did not separate aggression with a partner versus other people (Parks et al., 2008). In the one other study, Moore, Elkins, McNulty, Kivisto, and Handsel (2011) used a 60-day, prospective diary design to examine whether alcohol and marijuana were associated with aggression. They found that the odds of perpetrating psychological and physical aggression against a dating partner were higher on a drinking day relative to a nondrinking day (ORs = 2.19 and 3.64, for psychological and physical aggression, respectively) and as the number of drinks increased (ORs = 1.16 and 1.13, for psychological and physical aggression, respectively). That is, for each additional drink consumed the odds of psychological and physical aggression increased by 16% and 13%, respectively.

In contrast to the large body of research on alcohol and IPV, considerably less research has been conducted on marijuana use and IPV, with findings largely being mixed. For instance, a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies found marijuana to have a small, positive effect size in its relation to IPV (Moore et al., 2008). Nevertheless, temporal studies have failed to document a relation between marijuana use and increased odds of IPV (e.g., Moore et al., 2011). Further, one study demonstrated marijuana to be negatively associated with physical IPV perpetration (Stuart et al., in press). Thus, the primary aim of the present study was to attempt to replicate the temporal association between alcohol and IPV and to further examine the temporal relationship between marijuana and IPV perpetration.

Theoretical Considerations: The Moderating Effect of Angry Affect

Several theoretical models propose that certain proximal factors may moderate the link between substance use and IPV. For instance, Leonard (1993) proposed a theoretical model in which alcohol use does not always lead to IPV but instead interacts with situational factors, such as negative affect, to predict IPV. Indeed, Leonard’s theory of IPV has received cross-sectional support among men and women arrested for domestic violence (Stuart et al., 2006, 2008). Likewise, Finkel’s (in press) I3 model more specifically suggests that disinhibiting factors, such as alcohol, are particularly, and maybe even only, likely to lead to aggression when impelling factors (e.g., state anger) are present. This model has received ample empirical support as well (see Finkel, in press).

What factors should interact with the disinhibiting effects of alcohol to predict IPV? Angry affect may be one factor. Indeed, angry affect (e.g., anger, hostility, irritation) has received extensive theoretical attention as a risk factor for aggression broadly (e.g., Berkowitz, 1990) and IPV specifically (e.g., Bell & Naugle, 2008). A large body of previous research has demonstrated various indicators of negative affect (e.g., anger, hostility) to be consistently associated with IPV perpetration across populations (see review by Norlander & Eckhardt, 2005). In addition, Elkins, Moore, Mc-Nulty, Kivisto, and Handsel (2013) used a temporal design to demonstrate that angry affect (i.e., anger, hostility, and irritation) experienced prior to seeing one’s partner was associated with increased odds of aggression perpetration against a partner on the same day. Accordingly, negative affect may provide the impellance necessary for alcohol to lead to IPV. Nevertheless, we are not aware of any temporal research that has investigated the potential moderating role of proximal angry affect on the alcohol-IPV relation.

It should be noted that most, if not all, of the theoretical models of substance use and IPV have been restricted to the influence of alcohol on increasing the odds of aggression or the interaction of alcohol and proximal factors (e.g., anger) in predicting IPV. Given the mixed research on marijuana and IPV, it is not surprising that limited theoretical attention has been placed on the potential role of marijuana and angry affect interacting to predict increased odds of IPV. Still, given previous research demonstrating that negative affect is one factor that may contribute to marijuana use (e.g., Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005), it is possible that marijuana and angry affect may interact to predict IPV perpetration. Thus, the second aim of the current study was to examine the potential moderating effect of proximal angry affect on the temporal alcohol-IPV and marijuana-IPV perpetration relationships.

Alcohol, Marijuana, and Dating Violence Among College Women

Female college students are one population in which to examine the primary aims of the current study due to their high rates of alcohol use, marijuana use, and dating violence. For instance, approximately 63% of college women drink alcohol each year, a rate that is higher than their noncollege peers (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012). Approximately 30%–50% of undergraduate college women have consumed binge levels of alcohol (four or more drinks on one occasion) in the previous year (Johnston et al., 2012). Moreover, research indicates the past year prevalence of marijuana use among female college students is close to 50% (Yusko, Buckman, White, & Pandina, 2008). At the same time, each year approximately 80% of college women in dating relationships perpetrate psychological aggression and 20%–30% perpetrate physical aggression (Katz, Moore, & May, 2008; Shorey, Cornelius, & Bell, 2008). Females are also frequent victims of dating violence and are more likely than males to sustain injuries as a result of violence victimization (Archer, 2000; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). However, some research suggests that women initiate aggression more often than males (Capaldi, Kim, & Shortt, 2004) and perpetrate as much, if not more, aggression than their male partners (Archer, 2000; Straus, 2008). Additionally, alcohol use is robustly related to dating violence perpetration among college women (Shorey et al., 2011). Thus, alcohol use, marijuana use, and dating violence perpetration by female college students are all serious problems.

Current Study

The present study examined the temporal relationship between alcohol use, marijuana use, and negative affect and IPV perpetration, as well as whether negative affect moderated the temporal relation between alcohol and marijuana and IPV, using a daily diary design in a sample of dating college women. On the basis of previous research and theories of substance use and aggression, the following hypotheses were examined: (a) dating violence perpetration will be more likely to occur on drinking days relative to nondrinking days, (b) dating violence perpetration will not be more likely to occur on marijuana use days relative to nonuse days, (c) dating violence perpetration will be more likely to occur on days that participants experience higher (relative to lower) levels of angry affect, and (d) alcohol use and angry affect will interact to predict dating violence. Specifically, alcohol use will increase the odds of aggression when participants experience higher angry affect. We made no hypothesis concerning the moderating role of angry affect on the marijuana-IPV relation. We examined each hypothesis with respect to psychological and physical aggression, as well as three different indicators of alcohol use (i.e., any drinking, heavy drinking, and number of drinks consumed).

Method

Participants

Female undergraduate students from a large Southeastern university, recruited from psychology courses, participated in the current study. To be eligible students had to (a) be at least 18 years of age, (b) be in a current dating relationship with a partner who was a least 18 years old that had lasted at least 1 month in duration, (c) have consumed alcohol in the previous month, and (d) have an average of at least two contact days with their dating partner each week (i.e., face-to-face contact). A total of 284 female students met eligibility criteria. Of the 284 female students, 194 (68.3%) agreed to participate in a 1-hr survey session involving the completion of self-report measures that confirmed eligibility requirements and assessed other personal characteristics. After that session, all women were invited to participate in the 90-day daily diary study. Of those 194 women, 177 (91.2%) began the daily diary. The final sample is comprised of 173 female students who reported at least 1 day of face-to-face contact with their partner over the course of the 90-day diary portion of the study.

At the beginning of the study, the mean age of participants was 18.71 (SD = 1.27) and the average length of participants’ dating relationship was 16.39 (SD = 13.61) months. The majority of students were freshmen (69.4%), followed by sophomores (15.0%), seniors (8.1%), and juniors (7.5%). Ethnically, the majority of students identified as non-Hispanic Caucasian (85.5%); 8.7% identified as African American and the remainder identified as “other” (e.g., Hispanic, Asian American). The majority of students identified as being heterosexual (95.9%) and not currently living with their dating partner (96.5%).

Procedure

Each set of daily questionnaires was completed on SurveyMonkey.com. An e-mail was sent to each participant at the same time each day (12:00 a.m.) that contained a link to that day’s questionnaires. The link to each day’s surveys provided in the e-mail was only available for completion for a 24-hr period of time. Each set of questionnaires asked participants to report about their previous day’s behavior, defined as the time elapsed from when they awoke until they went to sleep. Completion of each day’s questionnaires took approximately 5 min. As compensation for participating in this study, participants received .50 cents for each completed daily survey (for a possible total of $45.00). As an incentive to increase completion rates, participants who completed at least 70% of the daily surveys were entered into a random drawing for a $100.00 gift card to an online retailer. Participants completed an informed consent prior to beginning the first assessment. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the first author’s institution.

Daily Questions

Contact with dating partner

Each day participants were asked if they had face-to-face contact with their partner during the previous day.

Dating violence

On days when participants had face-to-face contact with their dating partner, participants were asked to answer questions regarding their psychological and physical aggression perpetration by indicating whether they had engaged in both psychological and physical aggression using a “Yes/No” format. For physical aggression, participants were asked to report whether or not they had engaged in any of 11 behaviors included on the Physical Assault subscale of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996; Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003), which included, for example, “pushed or shoved my partner;” “slapped my partner;” “choked my partner;” and “kicked my partner.” Participants who reported they had engaged in these behaviors that day were coded with a “1” and participants who reported they had not engaged in these behaviors that day were coded with a “0.” For psychological aggression, participants were asked to report whether or not they had engaged in any of 10 behaviors on the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory–Short Form (Tolman, 1989), which included, for example, “called my partner names;” “treated my partner like an inferior;” “tried to keep my partner from doing things;” and “monitored my partner’s time.” We chose to list these behaviors from the PMWI rather than the CTS2 because the PMWI contains a more thorough list of psychologically aggressive behaviors and has been used to examine female-to-male psychological aggression perpetration (e.g., Taft et al., 2006). As with physical aggression, participants who reported they had engaged in these behaviors that day were coded with a “1” and participants who reported they had not engaged in these behaviors that day were coded with a “0.” Assessing violence dichotomously, as was done in the current study, is consistent with all temporal studies on the relation between alcohol, negative affect, and IPV (Elkins, Moore, McNulty, Kivisto, & Handsel, 2013; Moore et al., 2011; Parks et al., 2008; Rothman et al., 2012; Stuart et al., in press).

Alcohol use

Each day participants were asked if they had consumed alcohol and, if so, how many standard drinks of alcohol they consumed. Participants were provided with examples of a standard drink (e.g., one 12-ounce beer). If participants reported that they consumed alcohol on a day in which aggression occurred, they were asked to indicate whether they had consumed any alcohol prior to the aggression and, if so, how many standard drinks of alcohol they had consumed. To avoid confounding drinking after violence with drinking before violence, we coded any day on which drinking only occurred after violence as nondrinking days. In other words, we created a dummy code that indicated whether or not participants drank alcohol before any violence occurred, such that days in which people drank alcohol before perpetrating violence were coded with a “1,” days on which participants drank alcohol but did not perpetrate violence were coded with a “1,” days on which people drank alcohol after, but not before, they perpetrated violence were coded with a “0,” and days on which participants did not drink alcohol were coded with a “0.” We also created an index of the number of drinks consumed that was formed based on the number of drinks consumed on a drinking day. Finally, we also created a dummy code that differentiated heavy drinking days from nonheavy drinking days, where days on which participants reported consuming four or more standard drinks, which is considered heavy drinking for females (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism/NIAAA, 1995), were coded with a “1” and all other days were coded with a “0.” If alcohol was consumed both prior to and after aggression, only the number of drinks consumed prior to aggression was included in the index of number of drinks each day and for heavy drinking days.

Angry affect

To assess participants’ angry affect, we utilized three items from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Specifically, we used the adjectives of “anger,” “irritable,” and “hostile” to measure the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral components of angry affect (Elkins et al., 2013). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = very slightly to 5 = extremely; Watson & Clark, 1994) and was summed to create a total “angry affect” score. Participants were asked to answer these questions regarding their overall rating of affect for the entire previous day. These questions were asked prior to asking about violence each day. Our use of these three items and scoring method is consistent with the only previous study to examine the temporal relationship between angry affect and dating violence perpetration (Elkins et al., 2013). Across all days with face-to-face contact, the internal consistency for these three items was .76.

Marijuana use

Participants were also asked to indicate whether they had used marijuana each day and whether they had used marijuana prior to aggression. Marijuana use was dummy coded the same way alcohol use was dummy coded. Days in which marijuana use occurred following aggression were recoded into nonmarijuana use days.

Data Analytic Method

Multilevel modeling was used to examine whether the odds of perpetrating psychological and physical aggression were (a) higher on drinking days relative to nondrinking days (and higher with greater alcohol consumption; and higher on heavy drinking days relative to nonheavy drinking days); (b) higher on marijuana use days relative to nonuse days; (c) increased under conditions of angry affect; and (d) predicted by the interactions of alcohol use and angry affect and marijuana use and angry affect. To estimate the unique associations between aggression and drinking, marijuana use, and angry affect, we regressed each form of aggression onto each drinking variable, marijuana, and angry affect. In these analyses all drinking variables and marijuana use were uncentered and angry affect was grand-mean centered. Finally, we examined the interactive effects of drinking (marijuana use) and daily angry affect by forming the product between each drinking (marijuana use) variable and angry affect and entering each drinking (marijuana use) variable, one at a time, along with angry affect and the appropriate interaction term. The interactions between any alcohol use and angry affect, and any marijuana use and angry affect, were entered simultaneously in the models. The additional interaction analyses with heavy drinking and number of drinks controlled for the main effect of daily marijuana use. Angry affect and number of drinks consumed were standardized prior to forming interaction terms. All models were estimated using HLM 7 (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, Congdon, & du Toit, 2011). All slopes were fixed across individuals and a logit link function was specified using a Bernoulli sampling distribution due to the dichotomous nature of the dependent variables.

Significant interactions, like the ones predicted here, are sometimes decomposed by examining the simple effects on the focal variable at specific values of the moderating variable, such as one standard deviation above and below the mean (e.g., Aiken & West, 1991). In some cases, knowing the effect of one variable at a specific, meaningful value of another variable is of particular interest to researchers. However, as discussed by Cohen and Cohen (1983), one standard deviation above and below the mean is often an arbitrary cut-off that is sample-specific and, thus, may not provide the most accurate or complete theoretical and empirical description of an interaction because simple effects that emerge just beyond these (arbitrary) limits remain undetected. Therefore, we followed the procedures recommended by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006) to use the Johnson-Neyman method (Johnson & Neyman, 1936) to identify the exact levels of daily angry affect at which alcohol use (any, number of drinks, and heavy) and marijuana use demonstrated significant associations with aggression perpetration (i.e., the regions of significance of the simple effects of affect). This approach to decomposing interactions is an increasingly common method with clinically relevant data (e.g., Amir, Taylor, & Donohue, 2011; Beeble, Bybee, Sullivan, & Adams, 2009; McNulty & Russell, 2010).

Results

Daily Diary Descriptive Statistics

Participants completed a total of 9,477 (61%) of the 15,570 daily surveys. Out of the 90 possible daily surveys, 86 participants (49.7%) completed 61 or more days; 47 (27.1%) completed between 30 and 60 days; 36 (20.8%) completed between 10 and 29 days; and four (2.4%) completed less than 10 days. Thus, we had at least 1 month of data from 76.8% of the sample. Given that physical aggression was only possible on days in which partners have face-to-face contact, days in which no face-to-face contact occurred were omitted from analyses (4,729 days). This is consistent with previous research (Elkins et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2011). Thus, the final data set included 4,748 daily surveys that involved face-to-face contact between the 173 participants and their dating partners. Across the face-to-face contact days, participants reported a total of 80 acts of psychological aggression perpetration and 62 acts of physical aggression perpetration. Participants also reported a total of 654 drinking days (13.7% of face-to-face contact days) and 221 marijuana use days (4.6% of face-to-face contact days) during the study period. The mean daily angry affect score across all days was 3.83 (SD = 1.59; range = 3–15).

Main Effects of Alcohol, Marijuana, and Angry Affect on Dating Violence

The primary analyses examined the main effects of alcohol, marijuana use, and angry affect on the odds of psychological and physical aggression perpetration. As displayed in Table 1, analyses demonstrated that all three indicators of alcohol use were significantly associated with increased odds of psychological and physical perpetration controlling for daily angry affect and marijuana use, and daily angry affect was significantly associated with greater odds of psychological and physical dating violence perpetration controlling for each of the indicators of alcohol use and marijuana use. Marijuana use was positively associated with psychological aggression, but not physical aggression, controlling for alcohol use and negative affect.

Table 1.

Main and Interactive Effects of the Temporal Association Between Alcohol Use, Marijuana Use, Negative Affect, and Dating Violence Perpetration

| T | Psychological Aggression Perpetration

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | OR | CI | ||

| Alcohol (Yes/No) | 1.92* | .38 | .19 | 1.46 | [.99, 2.16] |

| Angry affect | 12.49*** | .38 | .03 | 1.47 | [1.38, 1.57] |

| Marijuana use | 3.15** | .88 | .28 | 2.42 | [1.39, 4.19] |

| Alcohol (Yes/No) × Angry affect | 2.56* | .38 | .15 | 1.47 | [1.09, 1.97] |

| Marijuana × Angry affect | 2.54* | .29 | .12 | 1.34 | [1.07, 1.69] |

| Alcohol (# drinks) | 2.05* | .07 | .03 | 1.07 | [1.00,1.15] |

| Angry affect | 12.59*** | .39 | .03 | 1.47 | [1.38, 1.57] |

| Marijuana use | 2.90** | .84 | .29 | 2.33 | [1.32, 4.13] |

| Alcohol (# drinks) × Angry affect | 3.31*** | .32 | .09 | 1.37 | [1.14, 1.67] |

| Alcohol (heavy drinking) | 5.33*** | .92 | .17 | 2.52 | [1.79, 3.80] |

| Angry affect | 12.59*** | .38 | .03 | 1.47 | [1.38, 1.57] |

| Marijuana use | 2.90** | .79 | .27 | 2.22 | [1.29, 3.80] |

| Alcohol (heavy drinking) × Angry affect | 4.26*** | .52 | .12 | 1.69 | [1.33, 2.15] |

| t | Physical Aggression Perpetration

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | OR | CI | ||

| Alcohol (Yes/No) | 2.01* | .52 | .26 | 1.68 | [1.01, 2.81] |

| Angry affect | 10.00*** | .37 | .04 | 1.46 | [1.35, 1.57] |

| Marijuana use | −.90 | −.41 | .46 | .66 | [.26, 1.63] |

| Alcohol (Yes/No) × Angry affect | .89 | .14 | .16 | 1.16 | [.84, 1.60] |

| Marijuana × Angry affect | .06 | .02 | .29 | 1.02 | [.57, 1.80] |

| Alcohol (# drinks) | 2.08* | .09 | .04 | 1.10 | [1.01, 1.21] |

| Angry affect | 10.14*** | .37 | .04 | 1.46 | [1.36, 1.63] |

| Marijuana use | −.94 | −.45 | .47 | .64 | [.25, 1.63] |

| Alcohol (# drinks) × Angry affect | 3.15** | .48 | .15 | 1.62 | [1.20, 2.19] |

| Alcohol (heavy drinking) | 2.89** | .78 | .27 | 2.19 | [1.28, 3.72] |

| Angry affect | 10.12*** | .37 | .04 | 1.46 | [1.36, 1.57] |

| Marijuana use | −.90 | −.39 | .44 | .67 | [.28, 1.59] |

| Alcohol (heavy drinking) × Angry affect | 1.99* | .36 | .18 | 1.43 | [1.01, 2.05] |

Note. SE = Standard error; OR = Odds ratio; CI = Confidence interval.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Interactive Effects of Alcohol, Marijuana, and Angry Affect on Dating Violence

The second set of analyses examined whether daily alcohol use, marijuana use, and daily angry affect interacted to predict the odds of dating violence (see Table 1). We first examined the interaction between daily alcohol use (yes/no) and daily angry affect, as well as the interaction between daily marijuana use and daily angry affect, in predicting dating violence perpetration. A significant interaction emerged for psychological aggression, but not physical aggression, for both alcohol and marijuana. For psychological aggression, results revealed that any alcohol use significantly increased the odds of aggression among women who experienced affect that was .85 SDs more negative than the mean but was unrelated to aggression at low levels of angry affect. In other words, women who experienced relatively high levels of angry affect and drank alcohol were more likely to perpetrate psychological aggression than women who experienced relatively high levels of angry affect but did not drink alcohol. For marijuana, results demonstrated that marijuana-use days increased the odds of psychological aggression among women who experienced affect that was .56 SDs more negative than the mean, but was unrelated to aggression among women who experienced less angry affect.

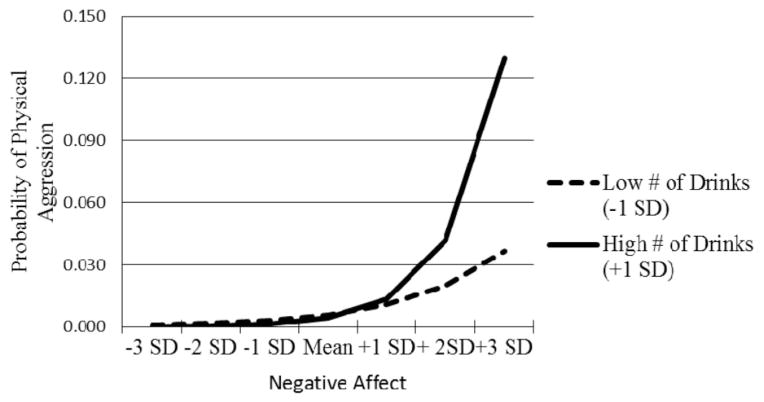

We next examined interactions between angry affect and number of drinks in predicting dating violence perpetration. Once again, significant interactions emerged for both psychological and physical aggression. For psychological aggression, the number of drinks consumed significantly increased the odds of aggression among women who experienced affect that was 0.33 SDs more negative than the mean, but was unrelated to aggression at low levels of angry affect. For physical aggression, the number of drinks consumed was significantly associated with increased odds of perpetration among women who experienced affect that was more than 1.41 SDs more negative than the mean, but was unrelated to aggression at low levels of angry affect (see Figure 1). In other words, women who experienced relatively high levels of angry affect were more likely to perpetrate both psychological and physical aggression with each drink.

Figure 1.

Negative Affect × Number of Drinks in Predicting Physical Aggression Perpetration.

Next, we examined interactions between angry affect and heavy drinking in predicting dating violence perpetration. Once again, significant interactions emerged for both psychological and physical aggression. For psychological aggression, heavy drinking was significantly associated with greater odds of perpetration among women who experienced affect that was more than 0.30 SDs more negative than the mean, but was unrelated to aggression at low levels of angry affect. For physical aggression, heavy drinking was significantly associated with greater odds of perpetration among women who experienced angry affect that was more than 0.44 SDs more negative than the mean, but was unrelated to aggression among women who experienced less angry affect. In other words, women who experienced relatively high levels of angry affect and drank heavily were more likely to perpetrate both psychological and physical aggression than women who experienced relatively high levels of angry affect but did not drink heavily.

Discussion

Results of the current study demonstrated that all three factors, acute alcohol use, marijuana use, and angry affect predicted increases in IPV. The odds of perpetrating psychological and physical aggression were increased (a) on drinking days relative to nondrinking days, (b) as the number of drinks consumed increased, and (c) on heavy drinking days relative to nondrinking days. These findings replicate those of Moore et al. (2011) in being the only known studies to demonstrate the temporal relation between alcohol use and increased odds of dating violence perpetration among college women. The odds of perpetrating psychological aggression, but not physical aggression, were also increased on marijuana-use days relative to nonuse days. Given that other studies have failed to document similar effects, however, this effect should be considered preliminary until replicated. Any attempts to replicate this finding may be most informative to the extent that they also further examine potential mechanisms responsible for this association (e.g., decreased relationship quality due to substance use). Finally, the odds of psychological and physical aggression perpetration were also both increased as proximal angry affect increased. This finding is consistent with the findings of Elkins et al. (2013).

Consistent with our hypothesis, alcohol use and angry affect interacted to predict aggression perpetration. That is, any alcohol use, the number of drinks consumed, and heavy drinking increased the odds of aggression perpetration when participants reported high levels of proximal angry affect, but was unrelated to aggression when participants reported low levels of proximal angry affect. Marijuana use was associated with increased odds of psychological aggression only on days when angry affect was high. To our knowledge, this is the first empirical study to demonstrate that alcohol and marijuana use interact with angry affect on the same day to increase the odds of aggression perpetration, consistent with theoretical conceptualizations of substance use and IPV (i.e., Finkel, in press; Leonard, 1993). These findings should be considered preliminary until replicated.

Clinical and Theoretical Implications

These findings have implications for our clinical and theoretical understanding of alcohol-related aggression. Most notably, they support the idea that one way to reduce aggression is by reducing alcohol use. A notable limitation of existing dating violence prevention programs has been a relative lack of attention placed on reducing substance use, particularly drinking. However, our findings, and that of others (e.g., Moore et al., 2011), suggest that reducing alcohol use broadly may reduce the odds of aggression perpetration. For instance, brief motivational approaches may be appropriate in college student samples involving drinkers who are not alcohol dependent and not seeking treatment. Interventionists could provide clients with personalized feedback on individual risk factors for substance-related aggression, such as drinking, or potentially smoking marijuana, when experiencing angry affect, which could be presented to participants using the nonconfrontational, supportive approach of motivational interviewing. Strategies could then be discussed to reduce the risk of aggression under these high-risk conditions. For instance, individuals could develop plans to either refrain from drinking, or, if they choose to drink, could implement harm reduction approaches for aggressive behavior, such as drinking away from their partner and/or agreeing not to see their partner until sober.

Our study also suggests that interventions to reduce alcohol-related aggression, and dating violence generally, may be most effective to the extent that they target individuals who are most prone to experience angry affect in general and after the consumption of alcohol or those who drink alcohol when experiencing angry affect. Such individuals may benefit from mindfulness interventions that attempt to increase psychological health by focusing on present moment experiences, increasing self-awareness, and learning that all experiences (e.g., emotions) naturally come and go, which helps to decrease reactive and impulsive behavior (Baer, 2003). Theoretically, one of the mechanisms through which mindfulness-based interventions are believed to promote psychological health is through decreases in angry affect, which is achieved through the enhancement of adaptive emotion regulation strategies (Hill & Updegraff, 2012). Indeed, research indicates that mindfulness interventions do effectively decrease negative affect in general (Baer, 2003). Thus, mindfulness-based interventions may help participants reduce the general experience of angry affect and/or learn more effective and adaptive ways to cope with angry affect when it occurs. Having reduced levels of general angry affect may, in turn, make it more likely that, when alcohol is consumed, affect will remain neutral or positive. Empirical research is needed, however, to determine whether mindfulness interventions adapted for alcohol-related aggression are effective.

Future Directions

It will be important for future research to replicate our findings in samples of men. We are unaware of any reason why the effects found in the current findings should not be similar for men. Alcohol is associated with male perpetrated aggression (Shorey et al., 2011), just as it is for women; angry affect is associated with male perpetrated aggression (Norlander & Eckhardt, 2005), just as it is for women; thus, we believe that the main effects of alcohol and marijuana use, and the interactive effects of alcohol and angry affect, should impact men the same way it did the women in the current study. Nevertheless, future research should examine this issue directly. Additionally, future research should examine the interactions between both partners’ alcohol use, marijuana use, angry affect, and aggression using a similar methodology as in the current study. For instance, it is possible that the odds of aggression would be considerably increased if both partners are drinking and experiencing angry affect. Understanding the interplay of substance use and angry affect of both partners will further advance our understanding of alcohol-related aggression.

Limitations

Although the current study has several notable strengths (e.g., temporal, daily diary design; high-risk sample for alcohol-related aggression), it also has limitations. One limitation concerns the assessment of angry affect prior to aggression perpetration. In the Elkins et al. (2013) study, they assessed angry affect immediately prior to seeing one’s partner each day. In our study, we assessed angry affect overall for each day, prior to asking about violence. We believe that each of these approaches has advantages and disadvantages. For instance, the Elkins et al. approach does not take into consideration how angry affect may change upon seeing a partner; affect may become more negative should partners argue upon seeing each other, or potentially even hours after seeing each other. In our approach, retrospective angry affect ratings may have been colored by whether aggression occurred or not. It is notable, however, that our findings and that of Elkins et al. are consistent despite methodological variation. Still, both approaches have limitations, and future research is needed that directly compares approaches. Another possibility would be to have participants rate angry affect multiple times each day, and/or when specific events occur (i.e., aggression) using ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methodology, which may increase the accuracy of angry affect reporting. This would likely reduce the chances that angry affect ratings would be influenced by whether aggression was present or not each day.

Other limitations of the current study include our use of a sample of undergraduate women who had consumed alcohol in the previous month, and who were primarily non-Hispanic Caucasian in ethnicity, which limits the generalizability of findings. Still, these findings provide important information on college women, a group that is at high risk for alcohol-related violence. We also did not obtain corroborating reports of aggression or alcohol use from participant’s partners and future research could improve upon our study by including both members of the dyad. We do not have information on the individuals who qualified for the study but chose not to complete the study, limiting our ability to determine whether the individuals who completed the study differed on key characteristics relative to individuals who did not complete the study. Further, although the daily diary design of the current study likely reduced retrospective recall bias, it is possible that some retrospective recall bias was still introduced due to the passage of time. Research that employs multiple surveys each day, or randomly prompts participants to rate behavior, may further reduce recall bias. Our daily compliance rate (61%) was relatively low, although we are unaware of any other 90-day daily diary study to compare our rate with. Still, this relatively low compliance rate is partially offset due to the increased power inherent in a daily diary design. Moreover, 76.8% of our sample completed at least 30 days, and approximately half of our sample completed 60 or more days. Still, it is possible that our compliance rates may have impacted findings and future researchers should try to improve daily compliance rates. It is also possible that participants may have had their own expectancies regarding the role of angry affect and alcohol in provoking violence, and it is possible that these expectancies and beliefs may have influenced the data.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that the odds of psychological and physical dating violence perpetration were increased on drinking days and with increases in angry affect, and that psychological aggression increased on marijuana use days. Moreover, our study was the first known empirical investigation to demonstrate that alcohol use and proximal angry affect interacted to predict aggression when angry affect was high. In addition to advancing our understanding of the temporal role of alcohol and marijuana use with dating violence perpetration, our study is the only known temporal investigation of a potential proximal, moderating variable (angry affect) of the alcohol-IPV link. The implications of our findings, combined with previous research, suggest that interventions for dating violence should focus their attention on reducing alcohol use, potentially with an enhanced focused on individuals who are likely to experience angry affect when drinking, as well as on decreasing general levels of angry affect through the generation of adaptive emotion regulation skills.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by Grants F31AA020131 and K24AA019707 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) awarded to the first and second authors, respectively.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Ryan C. Shorey, University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Gregory L. Stuart, University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Todd M. Moore, University of Tennessee, Knoxville

James K. McNulty, Florida State University

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Amir N, Taylor CT, Donohue MC. Predictors of response to an attention modification program in generalized social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:533–541. doi: 10.1037/a0023808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:651– 680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:125–143. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beeble ML, Bybee D, Sullivan CM, Adams AE. Main, mediating, and moderating effects of social support on the well-being of survivors of intimate partner violence across 2 years. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:718–729. doi: 10.1037/a0016140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell KM, Naugle AE. Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: Moving towards a contextual framework. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1096–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. On the formation and regulation of anger and aggression: A cognitive neoassociationistic analysis. American Psychologist. 1990;45:494–503. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.45.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Shortt JW. Women’s involvement in aggression in young adult romantic relationships: A developmental systems model. In: Putallaz M, Bierman KL, editors. Aggression, antisocial behavior, and violence among girls: A developmental perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press Publications; 2004. pp. 223–241. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression: Correlational analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins SR, Moore TM, McNulty JK, Kivisto AJ, Handsel VA. Electronic diary assessment of the temporal association between proximal anger and intimate partner violence perpetration. Psychology of Violence. 2013;3:100–113. doi: 10.1037/a0029927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel E. The I3 Model: Meta-theory, theory, and evidence. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology in press. [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O’Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CLM, Updegraff JA. Mindfulness and its relationship to emotional regulation. Emotion. 2012;12:81–90. doi: 10.1037/a0026355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, Neyman J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their applications to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs. 1936;1:57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2011. Volume II: College students and adults ages 19 –50. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Moore J, May P. Physical and sexual covictimization from dating partners: A distinct type of intimate abuse? Violence Against Women. 2008;14:961–980. doi: 10.1177/1077801208320905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Research monograph 24: Alcohol and interpersonal violence: Fostering multidisciplinary perspectives. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1993. Drinking patterns and intoxication in marital violence: Review, critique, and future directions for research; pp. 253–280. NIH Publication No. 93–3496. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Russell VM. When “negative” behaviors are positive: A contextual analysis of the long-term effects of problem-solving behaviors on changes in relationship satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98:587– 604. doi: 10.1037/a0017479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Elkins SR, McNulty JK, Kivisto AJ, Handsel VA. Alcohol use and intimate partner violence perpetration among college students: Assessing the temporal association using electronic diary technology. Psychology of Violence. 2011;1:315–328. doi: 10.1037/a0025077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Stuart GL, Meehan JC, Rhatigan DL, Hellmuth J, Keen S. Drug use and aggression between intimate partners: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:247–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The physicians’ guide to helping patients with alcohol problems. NIH publication no. 95–3769. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, NIAAA; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Norlander B, Eckhardt CI. Anger, hostility, and male perpetrators of intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:119–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Hsieh Y, Bradizza CM, Romosz AM. Factors influencing the temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and experiences with aggression among college women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:210–218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437– 448. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon R, du Toit M. HLM7: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Stuart GL, Winter M, Wang N, Bowen DJ, Bernstein J, Vinci R. Youth alcohol use and dating abuse victimization and perpetration: A test of the relationships at the daily level in a sample of pediatric emergency department patients who use alcohol. Journal of interpersonal violence. 2012;27:2959–2979. doi: 10.1177/0886260512441076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Cornelius TL, Bell KM. A critical review of theoretical frameworks for dating violence: Comparing the dating and marital fields. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Stuart GL, Cornelius TL. Dating violence and substance use in college students: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2011;16:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Correia CJ, Hansen CL, Christopher MS. An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:326–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:252–275. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Warren WL. The Conflict Tactic Scales handbook. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Meehan J, Moore TM, Morean M, Hellmuth J, Follansbee K. Examining a conceptual framework of intimate partner violence in men and women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:102–112. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Moore TM, Elkins SR, O’Farrell TJ, Temple JR, Ramsey S, Shorey RC. The temporal association between substance use and intimate partner violence among women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0032876. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Temple JR, Follansbee K, Bucossi MM, Hellmuth JC, Moore TM. The role of drug use in a conceptual model of intimate partner violence in men and women arrested for domestic violence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:12–24. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, O’Farrell TJ, Torres SE, Panuzio J, Monson CM, Murphy M, Murphy CM. Examining the correlates of psychological aggression among a community sample of couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:581–588. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Prevalence and consequences of male-to-female and female- to-male intimate partner violence as measured by the National Violence Against Women Survey. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:142–161. doi: 10.1177/10778010022181769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM. The development of a measure of psychological maltreatment of women by their male partners. Violence and Victims. 1989;4:159–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson DL, Clark LA. Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule (Expanded form) University of Iowa; Des Moines, Iowa: 1994. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusko DA, Buckman JF, White HR, Pandina RJ. Alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs and performance enhancers: A comparison of use by college student athletes and non-athletes. Journal of American College Health. 2008;57:281–290. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.3.281-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]