Abstract

Clinical presentation and histopathology of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) overlap syndrome (OS) are similar, but their management is different. We conducted a pediatric retrospective cross-sectional study of 34 patients with AIH and PSC. AIH had female predominance (74%) and was lower in PSC (45%). There was a trend toward higher frequency of blacks in PSC/OS (55%) compared to Caucasians (36%) and Hispanics (9%), but not race differences in AIH. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) was present in 75% of PSC/OS. Plasma cells were not specific for AIH (found in 42% of PSC). Concentric fibrosis was not reliable for PSC as was found in 46% of AIH. Conclusion: A combination of clinical history, laboratory tests, imaging studies and liver biopsy are required to confirm and properly treat AIH and PSC. Liver biopsy should be used to grade severity and disease progression, but cannot be used alone to diagnose these conditions.

Keywords: autoantibodies, cholestasis, cirrhosis, hepatitis, liver biopsy, pediatric

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) usually presents with nonspecific symptoms such as malaise, lethargy, arthralgia without arthritis [1] and in children, it can either present very acutely or more insidiously, but progressing rapidly and leading to cirrhosis in a relatively short period of time. In a large study of pediatric patients with AIH at the King’s College in London, it was found that 56% of their patients presented with an acute onset; these authors also found that 69% of children with type 1 AIH and 37% of those with type 2 developed cirrhosis [2].

AIH can simulate viral hepatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), Wilson’s disease, drug-induced hepatitis and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Some patients will present with other autoimmune disorders such as autoimmune thyroiditis, vitiligo, Sjögren syndrome, ulcerative colitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, vasculitis and celiac disease [3].

The clinical presentation and hepatic histopathology of AIH and sclerosing cholangitis tend to be very similar and sometimes the two conditions may overlap in the same patient producing the so-called overlap syndrome (OS). Sclerosing cholangitis is frequently associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) adding to the diagnostic complexity of these two entities. Some authors have suggested that “onion-skin” type of periductal fibrosis is virtually diagnostic of PSC [4]. Since pure sclerosing cholangitis is not an autoimmune disease, and immunosuppression is not required as in AIH, it is important to arrive to the correct diagnosis as early in the disease as possible. The International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) published a position statement regarding the controversial issue of OS [5]. They concluded that the diagnosis of large duct PSC should be established on typical cholangiographic findings. The group also mentioned that PSC should be considered in AIH patients with pruritus, cholestatic liver tests and histological damage to bile ducts and in those with a poor response to therapy. The IAIHG suggested that patients with overlapping features between AIH and PSC should be considered part of the “classical” diseases rather than OS. However, they may require specific therapeutic modalities to treat the cholestasis and autoimmune abnormalities.

We herein report our experience with a series of children and adolescents presenting to a tertiary medical center that were diagnosed and treated as AIH, PSC or OS.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Previous approval from the Hospital’s Institutional Review Board, the hospital’s surgical pathology database was searched for the 8-year period between January 1st, 2004 and December 31st, 2011 for liver biopsies with the diagnosis of AIH, PSC and OS. All histological slides from the three possible diagnoses were reviewed by two pediatric pathologists (MMR and CPR) and the clinical information was collected by two pediatric gastroenterologists (RB and LH).

The criteria used to classify the patients as AIH, PSC and OS were as follows: for AIH elevated transaminases, positive autoantibodies, normal cholangiogram if performed, exclusion of Wilson’s disease and viral hepatitis. For PSC classification, we used segmental ductal narrowing by ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography), MRCP (magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography) or percutaneous cholangiogram. Patients with segmental ductal narrowing and positive autoantibodies were considered OS, but for statistical purposed they were analyzed in a single group with patients who had PSC (PSC/OS group).

Thirty-three variables were included for the analysis. The following clinical data was collected: age at biopsy, gender, race, presence of absence of hepatomegaly and splenomegaly, diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue, IBD, other autoimmune disorders, ascites and imaging studies (MRCP and/or ERCP). We also collected laboratory data including: total bilirubin, AST (aspartate transaminases), ALT (alanine amino transferase), GGTP (gamma glutamyl transpeptidase), total serum protein, albumin, IgG (Immunoglobulin G), IgA (Immunoglobulin A), IgM (Immunoglobulin M), ANA (anti-nuclear antibody), ANCA (anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies), SMA (antismooth muscle antibody) and anti-LKM-1 (liver kidney microsomal type 1) antibody.

The hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E)-stained and trichrome-stained glass slides were retrieved from the files and were reviewed by two pediatric pathologists without knowledge of clinical information, previous findings in the surgical pathology report or the laboratory data. Histopathological variables analyzed included: chronic hepatitis, presence of plasma cells, bile duct damage, bile duct proliferation, concentric fibrosis, cholestasis, necrosis and stage of fibrosis by trichrome stain.

For statistical analysis, continuous variables were compared using either t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test and described using means or medias depending on the normality of the distribution. For categorical variables we used the Fisher’s exact test. Bonferroni correction for multiple tests was applied (α = 0.05/33) and a significance level of 0.0016 of was obtained.

RESULTS

Thirty-four children and adolescents with AIH, PSC/OS were studied and of these, 23 (68%) had AIH and 11 (32%) had PSC/OS. The average age at the time of the biopsy was 13 years with a range from 5 to 18 years.

Clinical information for patients in the two groups is shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences for age. Gender distribution demonstrated a trend towards greater proportion of females with AIH (74%) compared to PSC (46%). There was no significant difference for race within the AIH group, however, there was a higher proportion of blacks (55%) compared to Caucasians (36%) and Hispanics (9%). The most common sign of children and adolescents with AIH was hepatomegaly (71%) while in the PSC group it was present in 44%, followed by fatigue (74% and 63% respectively). Splenomegaly was detected in 45% of AIH patients and 33% of PSC/OS respectively). IBD was not present in any of our patients with AIH at the time of diagnosis; however, it developed in two patients after liver transplant. There was a significantly higher proportion of patients with IBD in the PSC/OS group (90%) compared to the AIH group (10%, P < .001).

Table 1. .

Demographic and clinical variables in both AIH and PSC groups.

| Variable | n | AIH (n = 21) | PSC (n = 12) | P value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age — mean (SD) | 34 | 13 (3.9) | 13 (2.2) | .768* |

| Sex — no. (%) | 34 | |||

| Male | 6 (26) | 6 (55) | .108 | |

| Female | 17 (74) | 5 (46) | ||

| Race — no. (%) | 33 | |||

| Black | 9 (39) | 6 (55) | .302 | |

| Hispanic | 9 (35) | 1 (9) | ||

| Caucasian | 6 (26) | 4 (36) | ||

| Hepatomegaly — no. (%) | 30 | |||

| Positive | 15 (71) | 5 (44) | .331 | |

| Negative | 6 (29) | 4 (56) | ||

| Splenomegaly — no. (%) | 29 | |||

| Positive | 9 (45) | 3 (33) | .250 | |

| Negative | 11 (55) | 6 (67) | ||

| Diarrhea — no. (%) | 29 | |||

| Positive | 4 (22) | 4 (36) | .033 | |

| Negative | 14 (78) | 7 (64) | ||

| Abdominal pain — no. (%) | 26 | |||

| Positive | 10 (59) | 8 (89) | .128 | |

| Negative | 7 (51) | 1 (11) | ||

| Fatigue — no. (%) | 27 | |||

| Positive | 14 (74) | 5 (63) | .442 | |

| Negative | 5 (26) | 3 (38) | ||

| IBD — no. (%) | 30 | |||

| Positive | 2 (10) | 9 (90) | <.001 | |

| Negative | 18 (90) | 1 (10) | ||

| Autoimmune disease — no. (%) | 28 | |||

| Positive | 5 (28) | 0 (0) | .087 | |

| Negative | 13 (72) | 10 (100) | ||

| Ascites — no. (%) | 25 | |||

| Positive | 5 (29) | 2 (25) | .607 | |

| Negative | 12 (71) | 6 (75) |

SD: Standard deviation.

Fisher’s Exact Test except where stated otherwise.

t-test.

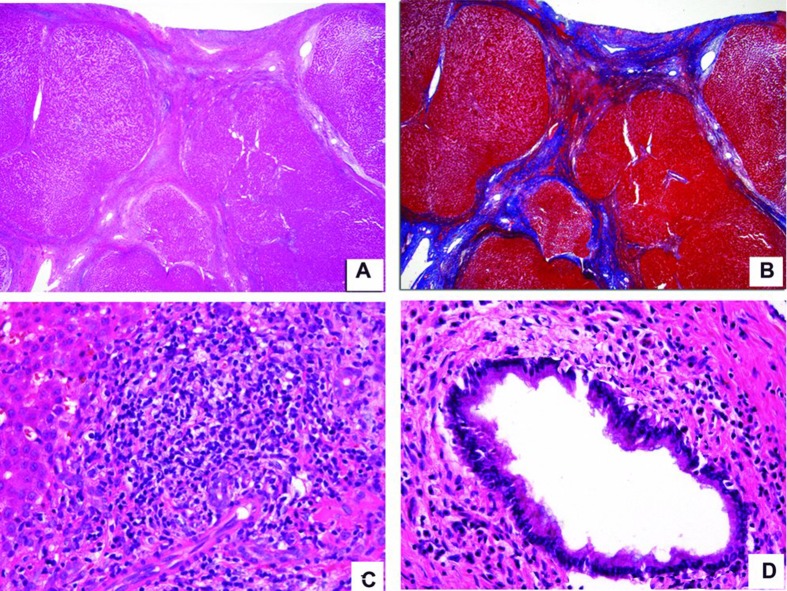

Histopathologic analysis is summarized in Table 2. The majority of liver biopsies in both groups disclosed chronic hepatitis (96% and 82% in AIH and PSC respectively.) The only patient in the AIH group that did not have evidence of chronic inflammation at the time of the biopsy was a 14-year-old girl who had an undifferentiated connective tissue disease with positive ANA, elevated transaminases, focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis and polyarthritis. This patient was extremely immunosuppressed and it is possible that for that reason did not show chronic inflammation. She subsequently died of culture-proven Pseudomonas bronchopneumonia. More than 50% of our patients were cirrhotic (Figure 1A & B). Other features such as chronic hepatitis (Figure 1C), bile duct damage with associated concentric fibrosis around bile ducts (Figure 1D) and cholestasis were present in both groups. It seems important to clarify that in our experience concentric fibrosis is much better observed in medium-sized bile ducts; therefore percutaneous needle biopsies may not be adequate to exclude concentric fibrosis. The differences between the two groups for all of the histologic features were not statistically significant. Hepatocellular necrosis was not a prominent feature in our series of patients.

Table 2. .

Histopathology variables in both AIH and PSC groups.

| Variable | AIH (N = 23) | PSC (N = 11) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic hepatitis — no. (%) | .239 | ||

| Positive | 22 (96) | 9 (82) | |

| Negative | 1 (4) | 2 (18) | |

| Plasma cells — no. (%)* | .316 | ||

| Positive | 14 (61) | 5 (55) | |

| Negative | 9 (31) | 6 (46) | |

| Bile duct damage — no. (%) | .519 | ||

| Positive | 18 (78) | 8 (73) | |

| Negative | 5 (22) | 3 (27) | |

| Bile duct proliferation — no. (%)* | .091 | ||

| Positive | 22 (100) | 8 (80) | |

| Negative | 0 (0) | 2 (20) | |

| Concentric fibrosis — no. (%)* | .495 | ||

| Positive | 10 (44) | 4 (36) | |

| Negative | 15 (57) | 7 (64) | |

| Cholestasis — no. (%) | .118 | ||

| Positive | 8 (35) | 1 (9) | |

| Negative | 15 (65) | 10 (91) | |

| Necrosis — no. (%)* | .239 | ||

| Positive | 1 (4) | 2 (18) | |

| Negative | 22 (96) | 9 (82) | |

| Fibrosis stage — no. (%)* | .815 | ||

| I | 4 (17) | 3 (27) | |

| II | 1 (4) | 1 (9) | |

| III | 3 (13) | 1 (9) | |

| IV | 15 (65) | 6 (55) |

Add to >100 or <100 due to rounding.

Fisher’s Exact Test.

Figure 1. .

Composite photomicrograph. A&B were taken from a patient with autoimmune hepatitis and C&D from another patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis. A. H&E-stained slide with a 4× lens demonstrates a cirrhotic liver with bands of bridging fibrosis and regenerative nodules. B. Trichrome-stained liver with a 4× lens taken at the same area as the H&E-stained section from A highlighting the bridging fibrosis in blue. C. H&E-stained slide with a 40× lens showing extensive chronic inflammation extending beyond the limiting plate and a few compressed bile ducts. D. H&E-stained slide with a 40× lens depicts moderate chronic inflammation surrounding the bile duct.

Regarding laboratory tests (Tables 3 and 4); there was no significant difference in the bilirubin, total protein or albumin concentration between patients with AIH and those with PSC/OS. However, there was a trend for increased concentration of transaminases in children with AIH compared to PSC/OS (Table 3), and a trend towards a higher concentration of GGTP in the PSC/OS group compared to those in the AIH group. There were no significant differences for IgG, IgM and IgA serum concentration between both groups (Table 4). Both SMA and ANA showed higher proportion of positive cases in the AIH compared to the PSC/OS group (Table 4). Two of the patients in the AIH group had positive anti-LKM-1 antibodies and were diagnosed as AIH type 2 (14%). None of the patients with PSC had positive serum anti-LKM-1 antibodies. ANCA positivity was not a feature of either AIH or PSC/OS.

Table 3. .

Clinical laboratory variables in both AIH and PSC groups.

| Variable | AIH (n = 23) | PSC (n = 11) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total bilirubin — median (IQR) | 3.3 (1.5 –7.9) | 5.6 (1.5 –37.3) | 1.000* |

| AST — median (IQR) | 443 (84 –1552) | 218 (148 –506) | .009* |

| ALT — median (IQR) | 218 (107 –1033) | 178 (94 –269) | .087* |

| GGT — median (IQR) | 69 (45 –132) | 118 (48 –572) | .033* |

| Total protein — mean (SD) | 6.8 (1.3) | 7.0 (1.8) | .646** |

| Albumin — mean (SD) | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.6 (1.0) | .132** |

SD: Standard deviation. IQR: Interquartile range.

Mann-Whitney U-test.

t-test.

Table 4. .

Autoimmunity laboratory markers in both AIH and PSC groups.

| Variable | n | AIH | PSC | P value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG — median (IQR) | (n = 13) | (n = 5) | .153 | |

| 2305 (1705 –3017) | 1785 (821 –2468) | |||

| IgA — median (IQR) | (n = 12) | (n = 4) | .716 | |

| 281 (232 –383) | 292 (156 –490) | |||

| IgM — median (IQR) | (n = 13) | (n = 4) | .141 | |

| 193 (130 –273) | 80 (60 –249) | |||

| ANCA — no. (%) | 17 | .765 | ||

| Positive | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Negative | 12 (92) | 4 (100) | ||

| ANA — no. (%) | 29 | .018 | ||

| Positive | 16 (76) | 2 (25) | ||

| Negative | 5 (24) | 6 (75) | ||

| SMA — no. (%)* | 22 | .064 | ||

| Positive | 11 (73) | 2 (29) | ||

| Negative | 4 (27) | 5 (71) | ||

| LKM — no. (%) | 20 | .479 | ||

| Positive | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | ||

| Negative | 12 (86) | 6 (100) |

Add to >100 or <100 due to rounding.

Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous variables and Fisher’s Exact Test for categorical variables.

Nine (41%) of the patients with AIH and two (18%) of the PSC/OS group underwent liver transplant. Two patients (9%) in the AIH group died and underwent autopsies: one died of culture-proven Pseudomonas bronchopneumonia and the other of hemorrhagic pancreatitis after severe liver rejection. Ten patients are alive and well, nine were lost to follow up and other two are having liver rejection. The outcome of the 11 patients in the PSC/OS group is as follows: Five are alive with disease, four are alive and well and two are lost to follow up. As far as we know, all patients with PSC/OS are alive so far.

DISCUSSION

Both liver histology and clinical presentation of AIH closely resemble viral hepatitis; therefore, in order to make the diagnosis of this entity one must exclude viral infections by serology. Among the histologic features, one that has been considered more helpful establishing an autoimmune etiology is the presence of plasma cells in the portal triads and sometimes in the acini [6], however, we found that this feature is not sufficiently specific because we detected plasma cells in 55% of biopsies from patients with PSC/OS confirmed by imaging studies. On the other hand, concentric fibrosis has been thought to be a reliable histologic diagnostic feature of PSC in adults [7]; but, we detected concentric fibrosis in 44% of biopsies that by autoimmune markers were later categorized as AIH. We think that our discrepancy in finding concentric fibrosis in many patients with AIH may be due to the fact that some of these specimens are explanted livers and the samples contained numerous medium-sized bile ducts where concentric fibrosis was observed, but it was not as obvious in small bile ducts from percutaneous liver biopsies that are performed at initial stages of the disease. Our series also showed abnormal bile duct proliferation in 100% of AIH patients and in 80% of the PSC group. Bile duct proliferation is a non-specific finding as can also be present in patients with extrahepatic biliary atresia, total parenteral nutrition hepatotoxicity, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3, cholangiolytic hepatitis B, choledochal cyst and inspissated bile duct syndrome. Neither cholestasis nor necrosis was a prominent histological feature in our series. The majority of our biopsies and/or explanted livers (65% for AIH and 55% for PSC) presented at advanced stages of fibrosis (stage IV). This could be due to the fact that our hospital is a tertiary care center with a Transplant Institute and therefore, many of the patients who cannot be managed in other medical centers because of advanced liver disease are transferred to us for possible liver transplant.

Interestingly, we found that several simple serum chemistry laboratory tests were relatively good indicators of either AIH or PSC/OS. On average, a higher concentration of both AST and ALT was seen in patients with AIH; this is consistent with immune-mediated hepatocellular damage. Conversely, the average concentration of GGT was higher in patients with PSC/OS as would be expected from biliary duct cellular damage [8].

The prevalence of AIH is one per 200,000 in the US general population [9], but it could be higher since many times it is not properly diagnosed and the patients present with advanced cirrhosis requiring a liver transplant. There are no large epidemiologic studies of prevalence for AIH and PSC/OS in African-Americans and even though our data may be biased because of the large black population that is usually served in our institution, the fact that the majority (55%) of our PSC/OS patients are black suggests a possible relation to race.

Regarding the pathogenesis of AIH, it is believed that an initial injury in genetically susceptible patients promotes the massive inflammatory response, mainly by CD4 + T-lymphocytes recognizing a self-antigenic peptide on the hepatocytes. A cascade of events promotes the release of cytokines that induces liver damage. A defect in immunoregulation affecting CD4 + CD25 + regulatory T cells has been demonstrated in AIH [10]. The pathogenesis of PSC seems to be due to chronic portal tract bacterial colonization, toxic bile acid metabolites produced by the intestinal flora, chronic infections and ischemic vascular damage. As expected, we found that 90% of patients with PSC/OS also have IBD [11].

Clinical presentation can guide the pediatric gastroenterologist or hepathologist to favor AIH or PSC because the degree of jaundice tends to be more severe in PSC than in AIH and the majority of patients with PSC also have IBD, but there is a subset that either never develop IBD or will develop it later in the course of PSC presenting a more challenging clinical picture. Our data showed that signs and symptoms such as hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, abdominal pain and fatigue are not helpful differentiating between these two entities. We have shown that laboratory tests are extremely helpful not only to rule out viral hepatitis, but also to find out if the patient has autoantibodies indicative of autoimmune disease. Cholangiographic studies are indicated whenever there is a suspicion of sclerosing cholangitis and lastly, liver biopsy is required not only to confirm the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis, but also to evaluate disease progression and guide the pediatric hepatologist deciding the proper treatment.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- [1].Lohse AW, Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2011;55:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gregorio GV, Portman B, Reid F, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in childhood: a 20 year experience. Hepatology. 1997;25:541–547. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Teufel A, Weinmann A, Kahaly GJ, et al. Concurrent autoimmune disease in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:208–213. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c74e0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kerkar N, Miloh T. Sclerosing cholangitis: pediatric perspective. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12:195–202. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Boberg KM, Chapman RW, Hirschfield GM, et al. Overlap syndromes: The International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAHG) position statement on a controversial issue. J Hepatol. 2011;54:374–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Suzuki A, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, et al. The use of liver biopsy evaluation in discrimination of idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis versus drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2011;54:931–939. doi: 10.1002/hep.24481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ludwig J. Surgical pathology of the syndrome of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13(Suppl 1):43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wright K, Christie DL. Use of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase in the diagnosis of biliary atresia. Am J Dis Child. 1981;135:134–136. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1981.02130260026008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Boberg KM. Prevalence and epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:347–359. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(02)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Longhi MS, Hussain MJ, Mitry RR, et al. Functional study of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in health and autoimmune hepatitis. J Immunol. 2006;176:4484–4491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fausa O, Schrumpf E, Elgjo K. Relationship of inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Semin Liver Dis. 1991;11:31–39. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]