Abstract

Novel synthetic compounds similar to heroin and its major active metabolites, 6-acetylmorphine and morphine, were examined as potential surrogate haptens for the ability to interface with the immune system for a heroin vaccine. Recent studies have suggested that heroin-like haptens must degrade hydrolytically to induce independent immune responses both to heroin and to the metabolites, resulting in antisera containing mixtures of antibodies (type 2 cross-reactivity). To test this concept, two unique hydrolytically stable haptens were created based on presumed structural facial similarities to heroin or to its active metabolites. After conjugation of a heroin-like hapten (DiAmHap) to tetanus toxoid and mixing with liposomes containing monophosphoryl lipid A, high titers of antibodies after two injections in mice had complementary binding sites that exhibited strong type 1 (“true”) specific cross-reactivity with heroin and with both of its physiologically active metabolites. Mice immunized with each surrogate hapten exhibited reduced antinociceptive effects caused by injection of heroin. This approach obviates the need to create hydrolytically unstable synthetic heroin-like compounds to induce independent immune responses to heroin and its active metabolites for vaccine development. Facial recognition of hydrolytically stable surrogate haptens by antibodies together with type 1 cross-reactivities with heroin and its metabolites can help to guide synthetic chemical strategies for efficient development of a heroin vaccine.

1. Introduction

The emergence of chemical addiction to heroin as a societal scourge, and the associated quest for an effective heroin vaccine, has led to challenging chemical, immunological, and biological problems [1,2]. Because the psychoactive effects of heroin require transfer of the drug from the blood to the brain, the theoretical basis underlying a possible vaccine is to induce high levels of antibodies that bind to the opiate to form immune complexes that cannot cross the blood-brain barrier [2,3]. In the case of heroin, induction of antibodies both to heroin and to its major metabolites (mainly, 6-acetylmorphine and morphine) are thought to be required because heroin is a small molecule which is rapidly deacetylated at the C3 and C6 positions after injection (Fig 1a) [4]. The metabolic products of heroin are also opiates, and an optimized heroin vaccine could presumably induce antibodies that bind both to heroin and to its active metabolites. However, heroin and its metabolites are haptens that are unable to induce antibodies by themselves. A vaccine therefore requires chemical conjugation of haptenic opiate surrogates to an acceptable protein carrier, and use of an adjuvant that is safe and effective for humans, in order to achieve a broad profile of high titer anti-hapten antibodies [3]. It is within this context that we have explored important chemical and immunological issues in this study.

Figure 1.

Structures of opiates (a) and surrogate haptens (b) coupled to TT. The blue arcs indicate the hypothetical immunologically-targeted faces of the opiates and the corresponding opiate surrogate haptens. The labeled letters on the chemical structures correspond to the letters on the adjacent space-filling models (ChemBio3D ultra presented in minimized energy configuration) of the opiate surrogate haptens. c. Antibody dilution curves and antibody titers to BSA-DiAmHap (left) and BSA-MorHap (right) induced in mice by immunization with TT-conjugates of DiAmHap or MorHap, respectively. Sera were from week 9. Values are the mean of triplicate determinations ± standard deviation. The titers expressed as endpoint titers.

From an immunologic standpoint, antigen binding sites of antibodies are believed to recognize the overall “shape” of an antigenic determinant in addition to its functional chemical groups [5]. However, it is often observed that antiserum induced by immunization can cross-react with molecules that are similar to the immunizing ligand. Two types of cross-reactivity of antibodies to different ligands have been defined: type 1 or “true” cross-reactivity, in which the ligands react with the same site on the antibody molecule but with different affinities; and type 2, also referred to as “partial” or “shared” cross-reactivity, in which the ligands each react with an independently induced subpopulation of antibodies having different binding properties in a heterologous antiserum [6,7].

Although haptens have been defined as comprising small functional groups corresponding to a single antigenic determinant [5,8], the challenge in the induction of type 1 cross-reactivity to a hapten lies in the multiple 3-dimensional surfaces, or “faces”, that can be presented to the immune system. Because of conjugation via a linker to the carrier protein the surrogate hapten is restricted in its freedom of motion, leading to a relatively fixed “front face” for induction of antibodies and a sterically blocked “back face” that cannot induce antibodies (Fig 1b). Here we apply synthetic chemistry to create carrier-conjugated surrogate heroin, 6-acetylmorphine, or morphine haptenic molecules that present the relatively immobilized front faces of hydrolytically stable opiate haptens such that antibodies are induced with the goal of exhibiting type 1 cross-reactivities. Based on the molecular faces available on the opiates (Fig 1a) and the front faces being presented by the haptenic opiate surrogates (Fig 1b), we hypothesized that the compound designated as DiAmHap having a linker conjugated to the bridgehead nitrogen might induce antibodies reactive with the 3,6-diacetyl groups of heroin. In contrast, the compound designated as MorHap with a linker conjugated to the C6 group might induce antibodies reactive with the analogous faces of 6-acetylmorphine or morphine (Fig 1b). However, because of the inevitable heterogeneity of binding specificities of induced antibodies, and because of similarities in the overall shape of each molecule (Fig 1b), there might be opportunities for cross-reactivities of a broad spectrum of induced antibodies with all of the target opiates.

One recently proposed strategy for developing a heroin vaccine had the goal of producing type 2 cross-reactivity to a chemically labile surrogate bridgehead nitrogen-linked heroin-like hapten conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) adsorbed to an aluminum-magnesium salt adjuvant (“Imject® Alum”) [9]. It was hypothesized that slow desorption of the labile heroin surrogate from the Imject® Alum would independently present degradation products to the immune system that would induce improved immune responses to 6-acetylmorphine and morphine. This type 2 immunization strategy resulted in antiserum that showed effectiveness against psychoactive effects of heroin in rats [9,10]. A study with a more stable surrogate bridgehead nitrogen-linked heroin-like hapten conjugated to KLH and adsorbed to Imject® Alum, both with and without CpG ODN adjuvant, a potent TLR 9 agonist, resulted in low titers and affinities of antibodies both to heroin and 6-acetylmorphine in mice [11].

This strategy of immunization with a bridgehead nitrogen-linked hydrolytically labile heroin-like surrogate hapten has led to the conclusion that a successful vaccine to heroin might require chemical lability of the surrogate bridgehead nitrogen-linked hapten for promotion of multiple metabolites to produce type 2 cross-reactivity in heterologous antiserum [10,11]. However, chemical instability of a surrogate hapten can result in a short shelf life prior to immunization, making it potentially disadvantageous as a formulation candidate for a practical vaccine. A further theoretical possibility with induction of type 2 cross-reactive antiserum is that the production of independent populations of antibodies by independent haptens might require a stronger and more complex series of immune responses. Here we hypothesize that DiAmHap, a chemically stable bridgehead nitrogen-linked heroin-like hapten presented to the immune system with a carrier known to be highly effective in humans (tetanus toxoid, or TT) and a potent adjuvant that has been widely used in humans (liposomes containing monophosphoryl lipid A) [12] can induce high titers of cross-reacting antibodies to heroin or to its major active metabolites.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

Two surrogate haptens (shown in Fig. 1b), and referred to, respectively, as DiAmHap [N,N'-((4R,4aR,7S,7aR,12bS)-3-(4-(3-mercaptopropanamido)butyl)-2,3,4,4a,5,6,7,7a-octahydro-1H-4,12-methanobenzofuro[3,2-e]isoquinoline-7,9-diyl)diacetamide], and MorHap [N-((4R,4aR,7R,7aR,12bS)-9-hydroxy-3-methyl-2,3,4,4a,7,7a-hexahydro-1H-4,12-methanobenzofuro[3,2-e]isoquinolin-7-yl)-3-mercaptopropanamide] were synthesized (manuscript in preparation). Liposomal lipids consisting of 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (DMPG); 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (DMPC), monophosphoryl lipid A (PHAD™) (MPLA), and cholesterol were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Bovine serum albumin (BSA), used as blocking reagent for ELISA, morphine sulfate, trichloroacetic acid and triisopropylsilane were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO). Heroin HCl and 6-acetylmorphine were from Lipomed Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Tetanus toxoid (TT) was purchased from Statens Serum Institut (Copenhagen, Denmark). BSA, used for coupling to haptens, SM(PEG)2 linker and BCA total protein assay kits were purchased from Pierce Protein Research/Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL). Immunolon 2HB flat ELISA plates were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Marietta, OH). Peroxidase-linked sheep anti-mouse IgG (γ-chain specific) was purchased from The Binding Site (San Diego, CA). 2,2'-Azino-di(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonate) peroxidase substrate system was purchased from KPL, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD).

2.2. Formulation of vaccines and immunization

DiAmHap and MorHap were coupled to TT as previously described [13]. Briefly, the trityl protection was removed from the haptens by dissolving the haptens in chloroform, treating with triisopropylsilane and trifluroacetic acid for 2 h at room temperature and evaporating the solvent under high vacuum overnight. The TT was incubated with SM(PEG)2 for 2 h and dialyzed overnight against PBS, pH 7.4, at 4°C as described [13]. The unprotected haptens were solubilized in water and mixed with the TT. Following incubation at room temperature for 2 h, they were dialyzed overnight against PBS at 4°C and the protein concentration was determined by BCA. The haptens attached to tetanus toxoid were quantified by MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy (11). The number of MorHap molecules or DiAmHap molecules attached per molecule of tetanus toxoid was 19 and 17, respectively.

Liposomes, consisting of DMPC:cholesterol:DMPG in a molar ratio of 9:7.5:1, were prepared as described [14]. The pre-formed liposomes were mixed 1:1 with DiAmHap-TT or MorHap-TT to give a dose of 10 μg TT per dose of 0.05 ml. The final vaccine contained 50 mM phospholipid liposomes containing 20 μg MPLA/dose in PBS, pH 7.4.

Female Balb/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) (5–6 weeks of age; 13/group) were immunized intramuscularly with 0.05 ml of the vaccines at weeks 0 and 6 weeks in opposite rear thighs. The animals were bled prior to the first immunization and 3, 6 and 9 weeks after the primary immunization. The 8 mice/group that were used for the antinociception assays were not bled at week 9 prior to injection of heroin.

2.3. ELISA

DiAmHap and MorHap were coupled to BSA using the same method described above for coupling to TT. Hapten-BSA (0.1 μg BSA/0.1 ml PBS, pH 7.4) was added to the ELISA plates and incubated at 4°C overnight. The remainder of the ELISA was conducted as described [13]. Briefly, the plates were blocked with blocker (1% BSA in 20 mM Tris-0.15 M sodium chloride, pH 7.4) for 2 h. Serum was diluted in blocker and added to the plates. Following incubation for 2 h at room temperature, the plates were washed with 20 mM Tris-0.15 M sodium chloride-0.05% Tween 20®. Peroxidase linked-sheep anti-mouse IgG diluted in blocker was added and the plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The plates were washed and substrate was added. After 1 h incubation at room temperature, the absorbance was read at 405 nm. Serum anti-MorHap IgG concentrations were quantified by ELISA with a standard curve of murine anti-morphine monoclonal antibody BD1263 (Abcam, Cambridge MA).

2.4. Competitive ELISA

Heroin HCl and morphine sulfate were dissolved in blocker. 6-Acetylmorphine was dissolved in DMSO at 10-fold higher concentration and then diluted 10-fold in blocker. Sera were diluted in blocker to give an ELISA absorbance of approximately 1.5. The inhibitors were diluted in 10-fold increments in a 96 well plate and mixed with diluted sera to give the final inhibitor concentrations indicated in Figs. 2–3. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, each serum-inhibitor mixture was added to ELISA plates that were coated with the indicated hapten-BSA and blocked with BSA. The ELISA was processed as described above. Competitive ELISAs were conducted on the individual animals in each group.

Figure 2.

Competitive inhibition in solid-phase ELISA of the binding of antibodies. a. Antibodies to MorHap to bound to BSA-MorHap inhibited by fluid phase opiates. Sera were from week 9. Values are the mean of triplicate determinations ± standard deviation. Comparison of competitive inhibition curves from the same the antisera for heroin with 6-acetylmorphine (no. 827, p=0.0002; no. 829, p=0.0385; no. 831, p<0.0001; no. 832, p<0.0001; no. 836, p<0.0001), heroin with morphine (no. 827, p<0.0001; no. 829, p<0.0001; no. 831, p<0.0001; no. 832, p=0.0003; no. 836, p=0.0004) and 6-acetylmorphine with morphine (no. 827, p=0.33; no. 829, p=0.015; no. 831, p=0.36; no. 832, p=0.51; no. 836, p=0.66) were calculated from normalized curves by 2-way ANOVA with Turkey's correction for multiple comparisons. The IC50 values were calculated and are shown in Table 1. Comparison of the normalized competition curves, grouped by competitive opiate, for heroin with 6-acetylmorphine (p<0.0001), heroin with morphine (p<0.0001), and 6-acetylmorophine with morphine (p=0.65) were calculated by 2-way ANOVA with Turkey's correction for multiple comparisons. b. Antibodies to DiAMHap bound to BSA-DiAmHap inhibited by fluid phase opiates. Sera were from week 9. Values are the mean of triplicate determinations ± standard deviation. There were no significant differences among heroin, 6-acetylmorphine and morphine competition for anti-DiAmHap binding in any of the sera from the immunized mice. The IC50 values were calculated and are shown in Table 2.

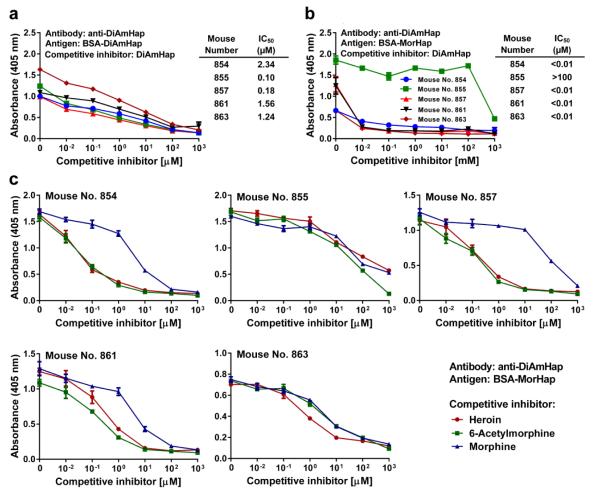

Figure 3.

Competitive inhibition of the binding of anti-DiAmHap sera. a. Inhibition of binding to DiAmHap by fluid phase DiAmHap. Trityl-DiAmHap competitively inhibited binding of anti-DiAmHap to BSA-DiAmHap coated ELISA plates. b. Competitive inhitition by trityl-DiAmHap of binding of anti-DiAmHap to BSA-MorHap coated ELISA plates. Sera were from week 9. Values are the mean of triplicate determinations ± standard deviation. IC50 values were calculated from the curves. c. Inhibition in solid-phase ELISA of the binding of antibodies to DiAmHap to BSA-MorHap by fluid phase opiates. Sera were from week 9. Values are the mean of triplicate determinations ± standard deviation. Comparison of competitive inhibition curves from the same antisera for heroin with 6-acetylmorphine (no. 854, p=0.98; no. 855, p<0.0001; no. 857, p=0.18; no. 861, p=0.34; no. 863, p=0.032), heroin with morphine (no. 854, p<0.0001; no. 855, p=0.73; no. 857, p<0.0001; no. 861, p<0.0001; no. 863, p=0.012) and 6-acetylmorphine with morphine (no. 854, p<0.0001; no. 855, p<0.0001; no. 857, p<0.0001; no. 861, p<0.0001; no. 863, p=0.91) were calculated from normalized curves by 2-way ANOVA with Turkey's correction for multiple comparisons. The IC50 values were calculated and are shown in Table 2. Comparison of the normalized competition curves, grouped by competitive opiate, for heroin with 6-acetylmorphine (p<=0.57), heroin with morphine (p<0.0001), and 6-acetylmorphine with morphine (p<0.0001) were calculated by 2-way ANOVA with Turkey's correction for multiple comparisons.

2.5. Nociception assay

To measure heroin-induced antinociception in mice the hot plate test was employed [15] and a hot plate analgesia meter was utilized (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). The hot plate was set at 58°C and the time was measured until the animal lifted one of its hind paws, with a cutoff time of 30 sec to prevent burning. At week 9, 8 of the 13 mice were randomly selected for the assay. The base line response prior to heroin injection was measured on the hot plate, and the animals were injected s.c. with 0.75 mg/kg of heroin HCl in saline (300 μg/ml) between the front shoulders, and 20 min later hot plate responses were measured again.

2.6. Data analysis

Antibody titers are expressed as endpoint titers which are defined as the dilution of sera at which the absorbance is twice background. The dilution curves of the individual mice were averaged to obtain a group endpoint titer. Calculation of the IC50 values and the statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism. IC50 values were calculated using nonlinear regression, one-site-fit logIC50 model [9]. For statistical comparison of the different inhibitors within a group of animals (Figs. 2a, 2b and 3c; Tables 1 and 2), the data were first normalized to correct for the different absorbances of the no inhibitor samples by calculating the percent binding. The normalized curves were compared using a 2-way ANOVA with Turkey's correction for multiple comparisons. A one-way ANOVA of the normalized data was used to compare the competition of DiAmHap with the anti-DiAmHap sera for binding to DiAmHap-BSA and 6-AmHap-BSA (Figs. 3a and 3b). The nociception data were analyzed by calculating the percent maximum potential effect (%MPE) using the following formula: %MPE = 100 × (injection latency time–baseline latency time)/(cutoff–baseline latency time). The data for the immunized mice were compared to the naïve (unimmunized) control mice using a T-test (unpaired, one tail).

Table 1.

Competition of sera from animals immunized with MorHap-tetanus toxoid with opiates for the binding to MorHap-BSA.a

| Inhibition concentration (IC50)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Number | Heroin (μM) | 6-Acetylmorphine (μM) | Morphine (μM) |

| 827 | >1000 | 369 | 232 |

| 829 | >1000 | >1000 | 201 |

| 831 | 477 | 11 | 10 |

| 832 | 306 | 11 | 19 |

| 836 | >1000 | 16 | 8 |

| Grouped serac | >1,000 | 67 | 36 |

Sera were from the week 9 bleed.

IC50 values were calculated from data shown in Fig. 2a using nonlinear regression one-site-fit logIC50 model.

IC50 values were calculated from the normalized competition curves, grouped by competitive opiate from the data of the individual antisera shown in Fig 2a.

Table 2.

Competition of sera from animals immunized with DiAmHap-tetanus toxoid with opiates for the binding to DiAmHap-BSA and MorHap-BSA.a

| Inhibition concentration (IC50) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capture antigen: DiAmHapb |

Capture antigen: MorHapc |

|||||

| Mouse Number | Heroin (μM) | 6-Acetylmorphine (μM) | Morphine (μM) | Heroin (μM) | 6-Acetylmorphine (μM) | Morphine (μM) |

| 854 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 3.82 |

| 855 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | 9.30 | 22 | 27 |

| 857 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 71 |

| 861 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 3.74 |

| 863 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | 0.71 | 3.27 | 3.16 |

3. Results

3.1 Induction of antibodies to TT-DiAmHap and TT-MorHap

Five mice were immunized i.m. at 0 and 6 weeks, and the average serum endpoint titers against the respective homologous surrogate haptens at 9 weeks were 3 × 106 for DiAmHap, and 2.5 × 106 for MorHap (Fig 1c). Anti-MorHap antisera obtained after 2 injections contained approximately 100 μg of anti-MorHap IgG per ml (data not shown).

3.2 Specificities of antibodies to TT-MorHap

The specificities of induced antibodies to surrogate haptens are often estimated by solid-phase enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) or fluid phase equilibrium dialysis with a radiolabeled tracer [4,9]. However, equilibrium dialysis requires inconvenient and sometimes difficult synthesis of a radiolabeled opiate. Competition by unconjugated fluid phase opiates of antibody binding by ELISA to the surrogate hapten, is often used to determine the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of antibodies to drugs [16]. Although IC50 is not a strict measure of antibody affinity per se, it is often used as a convenient method to estimate the relative ability of the fluid phase opiate to inhibit the binding of the antibody to the solid phase surrogate opiate-carrier complex. Figure 2a illustrates competitive inhibition by heroin, 6-acetylmorphine, and morphine of antisera from each of 5 mice immunized with TT-MorHap. As anticipated, greater inhibition of antibodies were exhibited by both fluid-phase 6-acetylmorphine and morphine than by heroin (p<0.0001) (Fig 2a and Table 1).

3.3 Specificities of antibodies to TT-DiAmHap

In contrast to MorHap, as shown in Fig 2b and Table 2 antibodies to DiAmHap unexpectedly were not inhibited at all by fluid-phase heroin, 6-acetylmorphine or morphine. These results could indicate either that antibodies to DiAmHap have no specificity for heroin and its degradation products at all, and that DiAmHap is thus a poor surrogate hapten, or that the affinities of antibodies for DiAmHap were so high that inhibition by fluid phase opiates could not occur, and DiAmHap might actually be a good surrogate hapten. To resolve this dilemma, we first demonstrated that antibodies to DiAmHap could be inhibited by fluid-phase DiAmHap and that the antibodies were highly specific for DiAmHap (Fig 3a). Antibodies to DiAmHap also cross-reacted with MorHap (Fig 3b). However, antisera from 4 of 5 mice exhibited binding of anti-DiAmHap antibodies to MorHap that were much more strongly competitively inhibited by fluid-phase DiAmHap, thus indicating that the affinity of cross-reactivity of anti-DiAmHap antibodies for solid-phase MorHap was lower than for solid-phase DiAmHap (p<0.0001 for Fig. 3b vs. Fig. 3a). As shown in Fig 3c and Table 2, competitive inhibition of binding of anti-DiAmHap antibodies to solid-phase MorHap by each of the target opiates occurred with apparent high affinities, with heroin = 6-acetylmorphine > morphine (p<0.0001 for heroin vs. morphine, and p < 0.0001 for 6-acetylmorphine vs. morphine).

3.4 Inhibition of heroin-induced antinociception

Each immunized mouse or non-immunized control mouse was tested for antinociceptive effects of injected heroin in the hot plate test. All of the mice immunized with MorHap, and 7 of 8 immunized with DiAmHap, had a reduced heroin effect and, as shown in Fig. 4, as a group the effects of each type of immunization resulted in significant inhibition of heroin-induced antinociception.

Figure 4.

Immunization effects on heroin-induced antinociception. Nine weeks after primary immunization, 8 non-immunized control animals and 8 animals immunized either with TT-MorHap or TT-DiAmHap, as indicated, were subcutaneously injected with 0.75 mg/kg heroin HCl. Twenty min after injection, the hot plate assay was performed. Values shown are %MPE ± S.D. Significance of %MPE of immunized animals was compared to the nonimmune animals and was calculated by an unpaired T-test.

4. Discussion

Although injected heroin is a potent opiate it undergoes rapid metabolism via deacetylation at the C3 and C6 positions to produce 6-acetylmorphine and morphine as its major active metabolites. Because of this, injected heroin can be viewed as a pro-drug because both it and its metabolites, each of which is an opiate, independently cross the blood-brain barrier to bind to the opiate receptor. One experimental approach to this problem has been to use a surrogate bridgehead nitrogen-linked heroin-like hapten that preserves the both the C3 and C6 acetyl groups of heroin [9,10]. After conjugation to a carrier protein (KLH) this “immunochemically dynamic” hapten undergoes rapid deacetylation, resulting in presentation of heroin and its major metabolites to the immune system, and induces antibodies that exhibit apparent affinities to heroin, 6-acetylmorphine, and morphine. In contrast to this labile “dynamic” hapten, antibodies to a stable bridgehead nitrogen-linked hapten, in which hydroxyls replaced the C3 and C6 acetyl groups, bound strongly to heroin and morphine, but lacked significant binding affinity to 6-acetylmorphine, and poorly blocked the biological effects of heroin in immunized rats [9]. In addition, the apparent affinities of mouse antibodies against this hapten to 6-acetylmorphine were actually reduced by using a potent adjuvant (CpG) [11]. An alternative bridgehead nitrogen-linked heroin-like hapten was also proposed that, like 6-acetylmorphine, preserved the C6 acetyl group but in which an amide replaced the C3 acetyl group of heroin [11]. Antibodies to this type of hapten exhibited apparent affinity to heroin and 6-acetylmorphine, and affinities were increased by using CpG adjuvant, but the antibodies did not bind to morphine. Based on antibody binding activity and inhibition of physiological effects of injected heroin, it was concluded that development of an effective heroin vaccine would require the use of a metabolically unstable bridgehead nitrogen-linked surrogate hapten to induce type 2 immune responses [10,11].

The above results with bridgehead nitrogen-linked surrogate haptens pose a formidable challenge for the design, and selection of surrogate haptens for vaccine development in which the haptens must be sufficiently stable for vaccine formulation but must induce antibodies that can block the biological effects of heroin and its active metabolites. An alternative approach by other groups has been to use C6-linked haptens rather than bridgehead nitrogen-linked haptens for coupling to carrier proteins to induce antibodies that bind to 6-acetylmorphine and morphine [17–19]. In the present study we have studied two hydrolytically stable surrogate haptens: DiAmHap, a bridgehead nitrogen-linked hapten which presents a front face similar to heroin; and MorHap, a C6-linked hapten which presents a front face similar to both 6-acetylmorphine and morphine (Fig. 1b). Each of these haptens induced antibodies that exhibited type 1 (true) cross-reactivity either with heroin and each of its metabolites (DiAmHap), or with 6-acetylmorphine and morphine but not heroin (MorHap). Although most of the heroin injected into rats is quickly metabolized by esterases in the blood, a small amount can be detected in the brain 1 min after injection, and the amount of intact heroin in the brain was not diminished by antibodies to a C6-linked morphine-like hapten [19]. In the case of DiAmHap, because of the high titers and apparent high affinities of antibodies induced to DiAmHap, and in view of the cross-reactivities of the antibodies to MorHap (Fig 3b), and the inhibition of the latter binding by fluid phase heroin, 6-acetylmorphine, and morphine (Fig 3c and Table 2), it appears that DiAmHap is thereby revealed as a potentially useful surrogate hapten for inducing high titers of a wide spectrum of cross-reacting antibodies with specificities to heroin, 6-acetylmorphine, and morphine. Antisera to DiAmHap and MorHap each inhibited antinociceptive effects of heroin injected into mice.

In view of the definition of a hapten as comprising a small functional group corresponding to a single antigenic determinant [5,8], it follows that antibodies to a chemically stable surrogate hapten (such as DiAmHap) comprise a unique population of antibodies against a single antigenic determinant. If they are cross-reactive with another hapten (such as heroin), the population of antibodies against the surrogate hapten is inherently exhibiting type 1 cross-reactivity. In contrast, if the antibodies are obtained against a hapten that is continually degrading (such as a surrogate hapten in which the C3 and C6 esters are intact), then multiple independent populations of antibodies against different haptens would be produced during degradation of the surrogate hapten, resulting in type 2 cross-reactivity. As shown in this study, candidate surrogate haptens can be created by chemical synthesis to present theoretical geometric faces and structural elements that may drive the immune system to specific recognition by antibodies through type 1 cross-reactivity. The tools of vaccinology, including potent adjuvant formulations combined with conjugation of surrogate haptens to suitable carrier molecules, must first be employed to produce high and prolonged titers of high affinity antibodies. The concept is thus validated that immunization with hydrolytically stable bridgehead nitrogen-linked or C6-linked haptens conjugated to TT and mixed with liposomal MPLA as a potent and clinically acceptable adjuvant can induce high titers of specific antibodies, and also that type 1 cross-reactivities of the antibodies can be achieved resulting in inhibitory effects on injected heroin in mice.

Acknowledgements and Disclaimers

This work was supported through a Cooperative Agreement Award (no.W81XWH-07-2-067) between the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine and the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (MRMC). The work was partially supported by an Avant Garde award to GRM from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH grant no. 1DP1DA034787-01). The work of KC, FL, MRI, AEJ, and KCR was supported by the NIH Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, NIH, DHHS. The authors thank Dr. Jay A. Berzofsky (NCI, NIH) for useful discussion of type 1 and type 2 cross-reactivity; Ms. Elaine Morrison, Ms. Courtney Tucker and Mr. Marcus Gallon provided outstanding technical assistance. Research was conducted in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals and adhered to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, NRC Publication, 1996 edition. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or NIH, or the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Author Contributions KCR, AEJ, AVM conceptualized the haptens; KCR designed the synthetic path for DiAmHap; AVM designed and synthesized MorHap; FL, JFGA, MRI, KC synthesized DiAmHap and intermediates, and obtained analytical and spectral data for DiAmHap and MorHap; OT participated in the chemical analyses of the surrogate haptens and determined the number of haptens bound to tetanus toxoid by mass spectroscopy; CRA, GRM, ZB designed and interpreted the immunological concepts and experiments that were carried out by GRM. CRA, AEJ, GRM wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Competing financial interests GRM, KCR, KC, FL, MRI, AEJ, AVM, CRA are co-inventors in a related patent application. The authors declare no other competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Anton B, Salazar A, Flores A, Matus M, Marin R, Hernandez JA, et al. Vaccines against morphine/heroin and its use as effective medication for preventing relapse to opiate addictive behaviors. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5(4):214–229. doi: 10.4161/hv.5.4.7556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinsey BM, Jackson DC, Orson FM. Vaccines against drug abuse. Anti-drug vaccines to treat substance abuse. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87(4):309–14. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen XY, Orson FM, Kosten TR. Vaccines against drug abuse. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(1):60–70. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stowe GN, Schlosburg JE, Vendruscolo LF, Edwards S, Misra KK, Schulteis G, et al. Developing a vaccine against multiple psychoactive targets: a case study of heroin. Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2011;10(8):865–75. doi: 10.2174/187152711799219316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner M. Antibodies. In: Roitt I, Brostoff J, Male D, editors. Immunology. 6th edition Mosby; Edinburgh: 2011. pp. 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berzofsky JA, Schechter AN. The concepts of crossreactivity and specificity in immunology. Mol Immunol. 1981;18(8):751–63. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(81)90067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berzofsky JA, Berkower IA. Antigen-antibody interactions and monoclonal antibodies. In: Paul WE, editor. Fundamental Immunology. 7th edition Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2013. pp. 183–214. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berzofsky JA, Berkower IA. Immunogenicity and antigen structure. In: Paul WE, editor. Fundamental Immunology. 7th edition Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2013. pp. 539–582. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stowe GN, Vendruscolo LF, Edwards S, Schlosburg JE, Misra KK, Schulteis G, et al. A vaccine strategy that induces protective immunity against heroin. J Med Chem. 2011;54(14):5195–204. doi: 10.1021/jm200461m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlosburg JE, Vendruscolo LF, Bremer PT, Lockner JW, Wade CL, Nunes AA, et al. Dynamic vaccine blocks relapse to compulsive intake of heroin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(22):9036–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219159110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bremer PT, Janda KD. Investigating the effects of a hydrolytically stable hapten and a Th1 adjuvant on heroin vaccine performance. J Med Chem. 2012;55(23):10776–80. doi: 10.1021/jm301262z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alving CR, Rao M, Steers NJ, Matyas GR, Mayorov AV. Liposomes containing lipid A: an effective, safe, generic adjuvant system for synthetic vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2012;11(6):733–44. doi: 10.1586/erv.12.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matyas GR, Mayorov AV, Rice KC, Jacobson AE, Cheng K, Iyer MR, et al. Liposomes containing monophosphoryl lipid A: a potent adjuvant system for inducing antibodies to heroin hapten analogs. Vaccine. 2013;31:2804–10. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matyas GR, Muderhwa JM, Alving CR. Oil-in-water liposomal emulsions for vaccine delivery. Methods Enzymol. 2003;373:34–50. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)73003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bannon AW, Malmberg AB. Models of nociception: hot plate, tail-flick, and formalin tests. Curr Protocol Neurosci. 2007;(Suppl 41):8.9.1–8.9.16. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0809s41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, Wang S, Fang G. Applications and recent developments of multi-analyte simultaneous analysis by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. J Immunol Methods. 2011;368(1–2):1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anton B, Leff P. A novel bivalent morphine/heroin vaccine that prevents relapse to heroin addiction in rodents. Vaccine. 2006 Apr 12;24(16):3232–40. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosten TA, Shen XY, O'Malley PW, Kinsey BM, Lykissa ED, Orson FM, et al. A morphine conjugate vaccine attenuates the behavioral effects of morphine in rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:223–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raleigh MD, Pravetoni M, Harris AC, Birnbaum AK, Pentel PR. Selective effects of a morphine conjugate vaccine on heroin and metabolite distribution and heroin-induced behaviors in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013 Feb;344(2):397–406. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.201194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]