Abstract

Aims:

Periodontal disease has been considered a systemic exposure implicated in a higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. The aim of the present study was to determine whether maternal oral health is associated with an increased risk of pre-eclampsia.

Subjects and Methods:

A case-control study was conducted which included 40 pregnant women patients admitted to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, J.N. Medical College, A.M.U, Aligarh. Pre-eclampsia was defined as classic triad of hypertension, proteinuria and symptoms such as swelling/edema esp. in hands and face, headache, visual changes etc., A periodontal examination was done during 48 h after child delivery. Maternal oral status was evaluated using gingival index by Loe and Silness, oral hygiene index (simplified) by greene and vermillion and periodontal pockets and clinical attachment level (CAL).

Statistical Analysis:

Null hypothesis that no difference exist between the two groups (pre-eclamptic and non-pre-eclamptic Group) was calculated using paired t-test, Chi-square and Mann-Whitney U statistical tests using SPSS 11.5 (Statistical Package for Social sciences, Chicago). P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results:

The amount of gingival inflammation, oral hygiene levels, pocket depth and CALs as measured by their respective indices were higher in the pre-eclamptic group when compared to non-pre-eclamptic group. Furthermore CAL was significantly increased in the test group. This study showed that pre-eclamptic cases were more likely to develop periodontal disease (P < 0.05). 30% of the test group and 65% of the case group had periodontal disease (P < 0.05) which had shown that pre-eclamptic cases were 4.33 times more likely to have periodontal disease (odds ratio = 4.33).

Conclusions:

Maternal oral status was determined to be associated with an increased risk of pre-eclampsia.

Keywords: Case-control study, periodontal disease, pre-eclampsia, pregnancy, risk factor

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal disease is a chronic infection of gingival and the dental supportive structures that is caused by periopathogenic microorganisms and is recognized by extensive damage to the dental supportive structures such as alveolar bone, which is accompanied by forming periodontal pocket and clinical attachment loss. The severity of periodontitis is measured by clinical attachment level (CAL); higher CAL is representative of severe disease.

Periodontal disease occurs in up to 15% of the fertile women and a large proportion of pregnant women.[1] Thus, researches were carried out on grounds of finding the link between periodontal disease and the complications of pregnancy such as pre-eclampsia. Subsequently, in an article in 2006, Offenbacher et al. were among the first who reported the relationship between periodontal disease on one hand and premature labor and low birth weight on the other.[2]

Pre-eclampsia is one of the hypertensive disorders that occur only during pregnancy and the postpartum period affecting both mother and unborn baby. It is considered as a syndrome and is defined by the classic triad of hypertension, proteinuria and symptoms like swelling/edema esp. in hands and face, headache, visual changes etc.[3] In general, it occurs after 20 weeks of gestation (in the late 2nd or 3rd trimesters of middle to late pregnancy). Pre-eclampsia and other hypertensive disorders are most common medical complications of pregnancy affecting 5-10% of all pregnancies. These disorders are responsible for 15% of maternal mortality.[1]

Women with poor periodontal health have increased risk of developing pre-eclampsia compared to those with normal oral hygiene.[4] Pre-eclampsia and atherosclerosis share some common epidemiologic risk factors and placental pathologic changes similar to atherosclerotic vascular changes have been described.[5] Endothelial damage in the placental vascular bed may be initiated by a number of mechanisms.[6] This damage results in oxidative and inflammatory vascular damage, which may ultimately result in the development of pre-eclampsia. The characteristic lesion of pre-eclampsia, which is designated as acute atherosis, is similar to the clinical and pathological alterations of atherosclerotic vascular changes.[7]

Chronic oral infections have been implicated as causative agents in a variety of systemic illnesses including atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and cerebrovascular ischemia.[8] In addition, periodontal disease has also been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Given the similarity between placental vascular damage and atherosclerosis and the potential for chronic oral infection to affect systemic organ systems, we sought to examine whether an association exists between maternal periodontal disease and the development of pre-eclampsia.

Thus this case control study was conducted to (1) assess the risk association between maternal periodontitis and pre-eclampsia before and after matching for known risk factors of pre-eclampsia (maternal age, chronic hypertension and primaparity) (2) to assess the extent and severity of periodontal parameters, such as gingival inflammation, oral hygiene, pocket depth (PD) and CALs.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The present study was conducted in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of a Medical College and was approved by the Research and Ethical Committee of the same university. Participants were informed of the aims of the study and provided with written informed consent.

An eligible sample was selected based on the availability and accessibility of women in the postpartum period within the 48 h of delivery. Data was collected through subject questionnaires, periodontal examination and medical records.

From May 2008 to October 2008, women 18-35 years of age who gave birth to live infants in the hospital unit were invited to participate in the study. Women were excluded from the study if, they

Were less than 18 years of age without a legal guardian

Had gestation period of greater than 26 weeks at the time of enrollment

Had multiple gestation, pre-gestational diabetes and heart murmur or heart valve disease, history of fenfluramine-phentermine use (unless a normal echocardiogram was documented)

Had any medical condition requiring antibiotic prophylaxis for dental treatment, human immunodeficiency virus infection

Had suffered a spontaneous abortion

Had undergone in-vitro fertilization.

Some of these exclusion criteria were adopted because they were determined to be confounders and risk factors for development of pre-eclampsia.[9,10]

During a 6 month study period of data collection, 40 women were found to be eligible and selected for a case-control study on adverse pregnancy outcomes and maternal periodontitis. Cases and Control assignment were done post-hoc. Women were divided into a control group (non-pre-eclamptic group) consisting of 20 non-pre-eclamptic women who gave birth to live term infants weighing >2500 g and a test-group (pre-eclamptic group) consisting of 20 pre-eclamptic women. Furthermore these 20 pre-eclamptic women were matched for age, chronic hypertension and primaparity with 20 non-pre-eclamptic women in the control group.

Medical data and case definition

Pre-eclampsia was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mm of Hg on two separate occasions after 20 week of gestation and ≥1+ proteinuria.[4] All subjects included in this study were tested for proteinuria, which was defined as protein concentration ≥0.30 g/dl on two separate urine samples taken 6 h apart. Upon a positive result, 24 h urine samples were collected for analysis of quantitative protein excretion during the monitoring period in cases of conservative routine procedures.[11]

Chronic hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or Diastolic pressure ≥90 mm Hg confirmed by multiple measurements and detected before conception or before 20 weeks of gestation.[12]

Smoking during pregnancy and alcohol use were defined as self-reported consumption during any trimester of pregnancy.[11]

Periodontal assessment

A full mouth periodontal examination was performed with University of North Carolina-15 periodontal probe.

Periodontal Examination was performed in the hospital bed under proper light and infection control conditions. Whenever necessary, teeth were cleaned with sterile gauze for adequate assessment of periodontal parameters. Clinical signs of inflammation, oral hygiene and tissue destruction were assessed by measuring gingival index,[13] oral hygiene index-simplified index,[14] PD and CAL respectively. All the parameters were recorded by a single trained examiner.

PD was measured as the distance from the gingival margins to the base of the clinical sulcus or to the base of the probable gingival crevice. CAL was determined as the distance from the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) to the bottom of the clinical sulcus or to the base of the probable gingival crevice.

For the purpose of this analysis, maternal periodontitis was defined as PD ≥ 4 mm and CAL ≥ 3 mm at the same site on at least 4 different non-neighboring teeth.[15]

Teeth were excluded from examination if the CEJ could not be determined properly, if they were in the process of eruption, if they had unsatisfactory restoration, extensive carious lesion or fracture or if they were third molars.

Statistical analysis

Eventually, the data thus obtained was analyzed by paired t-test, Chi-square and Mann-Whitney U statistical tests using SPSS 11.5 (Statistical Package for Social sciences, Chicago). P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

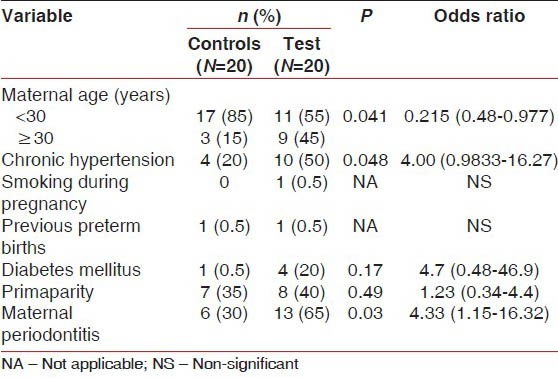

Demographic, Medical and Obstetric data for the Test and control groups before matching are detailed in the Table 1. The mean age of the sample was 28.52 ± 2.8 years. The Frequency of diabetes mellitus and smoking during pregnancy were low. Primaparity was noted in 35% of the women in the control group and 40% in the test group. The frequency of pre-eclampsia in the sample was 50%. The frequency of Periodontitis was 47.5% in the total sample 30% among non-pre-eclamptic women and 65% among pre-eclamptic women.

Table 1.

Demographic, obstetric and medical data for pre-eclamptic and non pre-eclamptic women

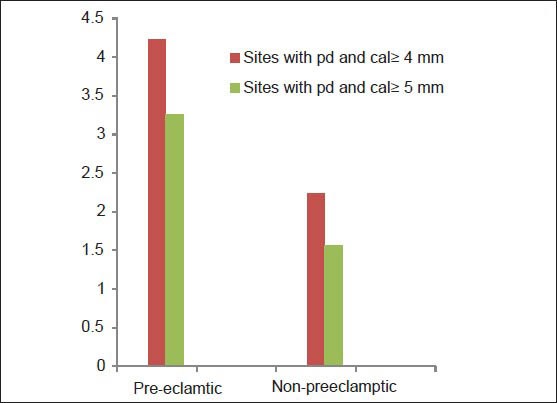

The mean number of sites with PD and CAL ≥ 4 mm or ≥5 mm was significantly greater in the test group [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Mean number of sites with pocket depth and clinical attachment level ≥4 mm and 5 mm in pre-eclamptic and non pre-eclamptic group

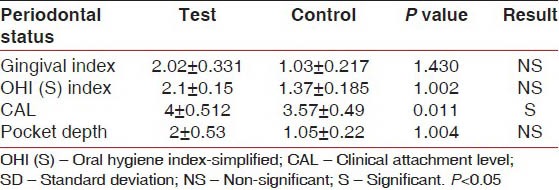

The extent of CAL was 3.57 ± 0.49 mm and 4 ± 0.512 mm in the control group and in the test group, respectively [Table 2]. Therefore, the Mann-Whitney U-test illustrated that the increase of CAL was higher in the test group than the control group (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Periodontal parameters (mean±SD) in test and control in terms of periodontal indices

The level of PD was higher in the test group compared with control group, but not statistically significant (P < 1.004) [Table 2]. The pregnant women in the test group were exposed to more severe periodontal diseases in comparison with the control group and the Chi-square test showed that the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.03) [Table 1].

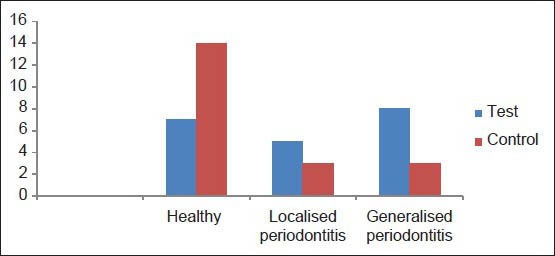

The distribution of the people in both groups according to the existence or nonexistence of the periodontal disease and division on the basis of pre-eclampsia [Figure 2] is indicated that if women suffer from pre-eclampsia, it is 4.33 times more probable to face the periodontal disease than the healthy women (odds ratio [OR] =4.33) [Table 1].

Figure 2.

The distribution of studied cases according to their conditions of periodontal disease and divided in relation to the condition of pre-eclampsia

DISCUSSION

Maternal clinical periodontal disease at delivery is associated with an increased risk for the development of pre-eclampsia, independent of the effects of maternal age, race, smoking, gestational age at delivery.

This research has shown that women suffering from pre-eclampsia, has higher severity of periodontal disease and these people are 4 times more prone to losing their periodontal attachments. Approximately, all existing studies had similar results if compared with our present study except one that did not confirm the link.[16] The inclusion and exclusion criteria, in that study were similar to the present study. Nonetheless, the reason for the difference may possibly lie in the different definitions made for the periodontal disease.

In other studies, the relationship between the periodontal disease and the incidence of pre-eclampsia has been reported with different ORs that is in the direction of the present study, despite the fact that in these researches, the existence and the severity of the periodontal disease were defined differently.[17,18] In one of these studies, the diagnosis of periodontal disease was based on PD and CAL was not taken into account. The OR of this study was 2.1.[4] In another study, the OR was 3.47.[7] In a study by Cota, certain intervening variables were not equalized in the case and the control groups including chronic hypertension, smoking and the number of labors. The OR was 1.88 in this study.[11] In the present study, an OR of 4.33 had resulted and it was higher than the aforesaid researches.

A parallel between the pathophysiologic consequences of pre-eclampsia and atherosclerotic disease has been suggested.[19] Atherosclerosis, like pre-eclampsia, is associated with endothelial dysfunction, which may be caused by oxidative stress and subsequent lipid peroxidation, hyperlipidemia, or hyperhomocysteinemia. Several other epidemiologic factors predispose to the development of both atherosclerosis and pre-eclampsia such as obesity, black race and preexisting hypertension. However, despite the similarities between atherosclerosis and pre-eclampsia, little is known about potential common putative factors.

Periodontal disease, a chronic oral Gram-negative infection, has been associated with atherosclerosis, thromboembolic events and hypercholesterolemia. In addition, oral pathogens have been detected in atherosclerotic plaques, where they can play a role in the development and progression of atherosclerosis leading to coronary vascular disease.[20] Periodontal disease may provide a chronic burden of endotoxin and inflammatory cytokines, which serve to initiate and exacerbate atherogenesis and thrombogenesis. It is possible that the placenta may be similarly burdened in pregnant women who develop pre-eclampsia.

In our study, mean gingival inflammation was more in pre-eclamptic group which indicates gingival inflammation could cause systemic inflammation leading to excessive production of inflammatory cytokines.[21]

Periodontal pockets and loss of CALs are clinical signs of existence of periodontal inflammation and putative periodontal pathogens within periodontal tissues. Presence of both these signs predisposes a patient to the increased amount of bacterimia during daily activities such as mastication, tooth brushing, dental flossing etc.[22] Both these parameters were significantly related to pre-eclamptic group in our study thus indicating translocation of microorganisms into the systemic circulation a possibility.

In one of the study conducted by Offenbacher in 2003 cohort of women has had umbilical cord serum assessed for the presence of fetal immunoglobulin M to oral pathogens. 57 (16%) of 351 fetal cord blood samples collected demonstrate fetal immunoglobulin M to the oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis, documenting a fetal humoral response to organisms distant from the intrauterine environment and suggesting that translocation of oral pathogens to the uteroplacental unit does occur.

Periodontal disease is characterized by periods of exacerbation interspersed with periods of remission and presents a local microbial burden that initiates local inflammation and local tissue destruction.[23] We hypothesize that women with active periodontal disease during pregnancy may have transient translocation of oral organisms to the uteroplacental unit, inciting placental inflammation or oxidative stress early in pregnancy, which ultimately produces placental damage and the clinical manifestation of pre-eclampsia.

In the present study, oral hygiene status was not significantly related to the development of pre-eclampsia. This indicates that variation exist among individuals in their susceptibility to periodontitis. Despite considerable accumulation of bacterial plaque, some individuals appear to be resistant to the disease process, whereas others develop disease. These differences relate primarily to variability in the host immune-inflammatory response to the infectious challenge.

Caution should be exercised when interpreting these data, as the etiology of both periodontal disease and pre-eclampsia is likely to be multifactorial. Apart from that, variability does occur due difference in methodology, selection of population, definition of disease and others. Further study on the maternal and fetal inflammatory responses to chronic oral infection and on placental pathology in women with periodontal disease has to be done to determine whether the relationship between periodontal disease and pre-eclampsia is causal or simply associative. If the relationship between maternal periodontal disease and pre-eclampsia risk proves causal in nature, then treatment of periodontal disease during pregnancy may represent a novel approach to the prevention of pre-eclampsia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank Dr. Sami Ahmed (Reader, Department of Periodontics and Community Dentistry Dr. Z.A Dental College, AMU, Aligarh) for his assistance in statistical work for this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Indian Council of Medical Research, Short Term Student Study

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boggess KA, Edelstein BL. Oral health in women during preconception and pregnancy: Implications for birth outcomes and infant oral health. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:S169–74. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0095-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Offenbacher S, Lin D, Strauss R, McKaig R, Irving J, Barros SP, et al. Effects of periodontal therapy during pregnancy on periodontal status, biologic parameters, and pregnancy outcomes: A pilot study. J Periodontol. 2006;77:2011–24. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Habli M, Sibai BM. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. In: Gibs RS, editor. Danforth's obstetrics and gynecology. 10th ed. Philadeilphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010. pp. 257–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boggess KA, Lieff S, Murtha AP, Moss K, Beck J, Offenbacher S. Maternal periodontal disease is associated with an increased risk for preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:227–31. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khong TY, Mott C. Immunohistologic demonstration of endothelial disruption in acute atherosis in pre-eclampsia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1993;51:193–7. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(93)90034-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davison JM, Homuth V, Jeyabalan A, Conrad KP, Karumanchi SA, Quaggin S, et al. New aspects in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2440–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000135975.90889.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canakci V, Canakci CF, Canakci H, Canakci E, Cicek Y, Ingec M, et al. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for pre-eclampsia: A case control study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44:568–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2004.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck JD, Offenbacher S, Williams R, Gibbs P, Garcia R. Periodontitis: A risk factor for coronary heart disease? Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:127–41. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bdolah Y, Karumanchi SA, Sachs BP. Recent advances in understanding of preeclampsia. Croat Med J. 2005;46:728–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riché EL, Boggess KA, Lieff S, Murtha AP, Auten RL, Beck JD, et al. Periodontal disease increases the risk of preterm delivery among preeclamptic women. Ann Periodontol. 2002;7:95–101. doi: 10.1902/annals.2002.7.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cota LO, Guimarães AN, Costa JE, Lorentz TC, Costa FO. Association between maternal periodontitis and an increased risk of preeclampsia. J Periodontol. 2006;77:2063–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:S1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Löe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol. 1967;38(Suppl):610–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soben P. Indices in dental epidemiology. In: Soben P, editor. Essential of preventive and community dentistry. 4th ed. New Delhi: Arya (MEDI) Publishing House; 2004. pp. 311–59. [Google Scholar]

- 15.López NJ, Smith PC, Gutierrez J. Higher risk of preterm birth and low birth weight in women with periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 2002;81:58–63. doi: 10.1177/002203450208100113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khader YS, Jibreal M, Al-Omiri M, Amarin Z. Lack of association between periodontal parameters and preeclampsia. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1681–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Contreras A, Herrera JA, Soto JE, Arce RM, Jaramillo A, Botero JE. Periodontitis is associated with preeclampsia in pregnant women. J Periodontol. 2006;77:182–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunnen A, Blaauw J, van Doormaal JJ, van Pampus MG, van der Schans CP, Aarnoudse JG, et al. Women with a recent history of early-onset pre-eclampsia have a worse periodontal condition. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:202–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sattar N, Bendomir A, Berry C, Shepherd J, Greer IA, Packard CJ. Lipoprotein subfraction concentrations in preeclampsia: Pathogenic parallels to atherosclerosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:403–8. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(96)00514-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haraszthy VI, Zambon JJ, Trevisan M, Zeid M, Genco RJ. Identification of periodontal pathogens in atheromatous plaques. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1554–60. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins JG, Windley HW, 3rd, Arnold RR, Offenbacher S. Effects of a Porphyromonas gingivalis infection on inflammatory mediator response and pregnancy outcome in hamsters. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4356–61. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4356-4361.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geerts SO, Nys M, De MP, Charpentier J, Albert A, Legrand V, et al. Systemic release of endotoxins induced by gentle mastication: Association with periodontitis severity. J Periodontol. 2002;73:73–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otomo-Corgel J, Steinberg BJ. Periodontal medicine and the female patients. In: Rose LF, editor. Periodontal Medicine. 1st ed. London: B.C. Decker; 2000. pp. 151–65. [Google Scholar]