Abstract

Background:

Oral hygiene is intimated in health of all parts of the body including oral cavity. The understanding of actual practices in keeping the oral heath at standard based on patient's perceptions of oral health care is vital. Understanding the effect of gender on oral health would facilitate the development of successful attitude and behavior modification approach towards sustainable oral health.

Purpose of Study:

To evaluate awareness regarding oral hygiene practices and exploring gender differences among patients attending for oral prophylaxis.

Materials and Methods:

A survey was conducted among 250 patients attending the department of periodontology, Maulana Azad institute of dental sciences for oral prophylaxis. A structured questionnaire was used to collect information regarding practices and perception about oral hygiene.

Results:

Majority of the patients (60.4%) felt that oral hygiene is mandatory for overall health of the body. The use of toothpaste and toothbrush (83.6%) was the most preferred cleaning aid among the study population in the present study. The major constraint for avoiding dental examination was no felt need (41.2%) followed by cost of dental treatment (26.8%) and time constraints (24.0%).

Conclusions:

Professional plaque removal and regular follow-up combined with oral hygiene instructions to the patients can minimize the level of gingival inflammation and swelling. The poor resources for dental care, common malpractices and nonavailability of professional care are the main barriers in seeking optimum oral hygiene.

Keywords: Dental care, oral hygiene, oral health, professional plaque removal

INTRODUCTION

Oral diseases constitute public health problem in developing countries due to their high prevalence, economic consequences, and negative impact on the quality of life of affected individuals.[1] Oral diseases adversely affect concentration, interpersonal relationship, and productivity due to the intricate relationship between oral health and general health. Prevention of oral disease can be achieved by optimizing the oral health practices in the form of proper tooth brushing, use of dental floss, dental visits at regular intervals, and proper dietary practices.[1]

The clinical concept that the maintenance of an effective plaque control is the cornerstone of any attempt to prevent and control periodontal diseases established since 1950s still remains valid.[2] The understanding of actual practices in keeping the oral heath at standard based on patients’ perceptions of oral health care is vital. Oral health is about more than shining white teeth and sweet breath. The practices and perceived access barriers have been related to oral health.[3] Patient's perception of the quality of dental care provision and their intent on re-accessing a dental service may be associated with a practitioner's professionalism, empathy, and delivery of oral hygiene advice.[4]

Dental professionals are faced with a number of apparent paradoxes when it comes to advising patients on the most appropriate strategy for plaque control.[5] Oral care, as part of general health self-care, comprises wide spectrum of activities ranging from care, prevention, and diagnosis to seeking professional care. Oral self-care practices have been proved to be an effective preventive measure at individual level for maintaining good oral health as a part of general health.[6]

The studies available in the literature on gender differences in relation to oral health were conducted in Asia (Japan), Europe (Sweden), and Middle East (Jordan), Kuwait and Palestine and North Africa (Libya).[1] The findings from these studies consistently revealed that females are more informed about tooth brushing, have more interest in oral health and perceive their own oral health to be good to a higher degree than males. They also exhibit more positive dental health attitude and better oral health behavior (tooth brushing frequency; using dental floss; regular dental visits) than their male counterparts.[1]

Limited literature is available on the practices and perceptions of oral hygiene among the Indian population. Therefore, a hospital based study was conducted to evaluate awareness regarding oral hygiene practices among patients attending for oral prophylaxis and explore gender differences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A face to face interview was conducted to collect data among patients visiting the department of periodontology, Maulana Azad institute of dental sciences, New Delhi, using a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire included questions regarding the oral hygiene practices and perceptions about the relationship of oral health with the oral hygiene practices.

Sample size calculation

The sample size of 250 was determined according to the results of the pilot study. The results of the pilot study showed that out of 20 patients, 80% reported that oral hygiene is mandatory for overall health of the body.

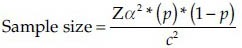

Sample size was calculated as follows using the following formula:

Where:

Z = Z value (1.96 for 95% confidence level)

p = percentage of picking a choice, expressed as decimal

This was found to be 80% for the present study which was expressed as 0.80.

c = confidence interval, expressed as decimal

So, the sample size was calculated as per formula

The sample size was calculated to be 246 which was rounded off to 250. A cross-sectional survey was conducted from June to August 2012 among 250 patients attending Department of Periodontics, Maulana Azad Institute of Dental Sciences for oral prophylaxis.

Inclusion criteria

Systemically healthy individuals aged between 20-60 years

The patients willing to give informed consent were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with history of systemic disease (debilitating disease or any condition having a substantial effect on oral health)

Pregnancy and lactation

Use of tobacco in any form

Undergone oral prophylaxis during the past 6 months.

Data collection

The study participants were recruited by non-probability convenience sampling method and included patients visiting the department of periodontology for oral prophylaxis. A total of 525 patients were screened and 250 patients were selected which satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The socio-economic status of the patients was assessed using the Kuppuswamy scale[7] which is based on income, education, and occupation. A weightage is assigned to each variable according to seven point predefined scale. The total of three weightages gives the socio-economic status score which is graded to indicate the five classes.

The different occupational categories are classified as follows:

Unemployed category means those who have no employment or activity for their livelihood

Unskilled worker is defined as those workers whose work requires no intensive training or special skill such as beedi, hotel, construction, fishing, street vending, head load work etc

Semiskilled workers are those whose work requires some type of skill like tailors, embroidery workers, weavers etc

Skilled workers are those workers whose work requires some sort of regular training and skill such as electricians, welders, plumbers and drivers of different motor vehicles

Clerk, shop owner, businessmen, farm or plantation owner, government servants of class III category, etc., belong to category 5

Semi-professional category includes school teachers, class 1 and class II officers in Govt. services and companies

Professional category includes doctors, advocates, engineers, chartered accountants, or such persons with professional qualification.

Ethical clearance

The ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethical committee. The informed consent was obtained from the patients who participated in the study.

Statistical analysis

Data was entered into Microsoft excel and analyzed using SPSS version 17.0. Descriptive statistics (Number and percentage of responses for the questions related to the oral hygiene practices including the demographic information) were calculated for response items. Chi-square test was applied for comparison of the attitude regarding the oral health and oral hygiene practices among males and females.

RESULTS

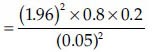

The study population included 134 (53.6%) male and 116 (46.4%) female patients and the mean age of the patients was 36.86 ± 12.37 (Range 20-60) years. The demographic profile of the population is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The demographic profile of the population

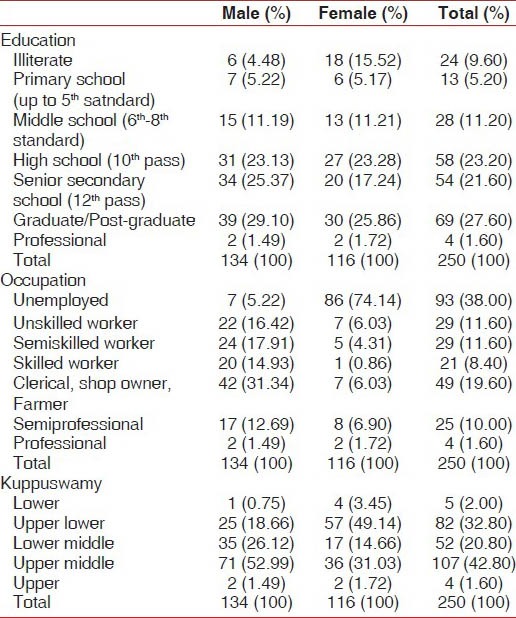

Majority (n = 151, 60.4%) of the patients felt that oral hygiene is mandatory for overall health of the body with more number of males (64.1%) having this perception regarding the importance of oral hygiene for over-all health as compared to females (56.0%). However, there were no significant differences in this perception among males and females [Table 2].

Table 2.

Distribution of the oral hygiene practices according to gender

The use of toothpaste and toothbrush (n = 209, 84.4%) was reported to be the most common cleaning aid for oral prophylaxis among the study population. There were no statistically significant gender differences with regards to the use of cleaning aids among the study participants but more number of females (n = 103, 88.8%) reported use of toothbrush in comparison to males (n = 108, 80.6%). Whereas the use of Finger and toothpowder/toothpaste was more among males (11.9%) when compared to females (4.3%) [Table 2].

Most of the patients (n = 137, 54.8%) reported cleaning their teeth once daily only. Majority of the males (n = 82, 61.2%) reported once daily oral hygiene practice whereas twice daily oral hygiene practice was more common among females (n = 59, 50.9%). There were no statistically significant differences between males and females with respect to the frequency of cleaning teeth [Table 2].

There were no significant differences between males and females with respect to duration of cleaning teeth with most of the patients cleaning their teeth for 3-5 minutes (n = 118, 47.2%) whereas (n = 42, 16.8%) patients cleaned their teeth for more than 5 minutes [Table 2].

Most of the patients changed their toothbrush once in 3 months (n = 124, 49.6%). There were gender differences in relation to change of toothbrush that ware statistically significant (P < 0.05) with females (53.4%) more frequently changing their toothbrush every 3 months in comparison to males (46.3%) and 24.1% females changing their toothbrush once every 6 months in comparison to 12.7% males [Table 2].

The rinsing of mouth with plain water after meal was reported by majority (n = 137, 54.8%) of the patients whereas only 8 (19.2%) patients rinsed their teeth once in the morning. There were no gender differences with respect to rinsing of mouth with water [Table 2].

The cleaning of tongue was reported by (n = 168, 67.2%) patients with males (n = 96, 71.6%) using tongue cleaner more frequently than (n = 72, 62.1%) females. The use of Tongue cleaner was reported by (n = 91, 36.4%) patients, followed by Toothbrush (n = 53, 21.2%) and use of other aids such as finger (n = 24, 9.6%). As such, there were no statistically significant differences between males and females with respect to the use of aids for tongue cleaning [Table 2].

The use of interdental aid was significantly (P < 0.05) more among females (n = 28, 24.1%) in comparison to males (n = 14, 10.5%). The use of various types of inter-dental aids among males and females was found to be statistically non-significant (P-value < 0.05) [Table 2].

A large proportion (53.6%) of the patients reported not visiting a dentist since last 12 months. Majority (n = 165, 66.0%) of the patients in the present study visited a dentist for oral prophylaxis only if a problem is there whereas (n = 72, 28.8%) had never visited a dentist for oral prophylaxis. A significantly (P < 0.05) more number of males (n =48, 35.8%) in the present study visited a dentist for routine oral hygiene maintenance in comparison to females (n =23, 19.8%) [Table 2].

Most of the patients (n =103, 41.2%) avoided dental examination for oral hygiene as they did not feel any need for it followed by Cost (n = 67, 26.8%) and then time constraint (n = 60, 24.0%). The females did not visit for a routine dental check-up due to the cost factor (n = 44, 37.9%) and the males did not feel any need for oral prophylaxis (n = 65, 48.5%) [Table 2].

DISCUSSION

In this study, 60.4% respondents believed that oral hygiene is considered to play a mandatory role in over-all health of the body which was substantially lower than the study conducted by Ali et al. (81%) in Karachi.[5] The majority of the patients in the present study used toothpaste and toothbrush (83.6%) for cleaning their teeth whereas Finger and Toothpowder was used by (7.6%) of the patients which was similar to the study conducted by Ali et al.[5] in which, (88.0%) patients had preferred practices of using tooth paste followed by tooth powder (5.76%) and Miswak (2.64%), respectively, and Hind Al-Johani[2] where almost all the patients (95.4%) used tooth brush for cleaning their teeth.

Currently at global level, dental caries and periodontal disease comprise a considerable public health problem in the majority of countries.[8] There have been wide disparities among developed and developing countries in relation to epidemiologic indicators of oral disease.[9] Although tooth brushing is the most popular oral hygiene practice across the world, regular tooth brushing appears less common among older people than the population at large.[10] This finding have been found to be consistent with other studies conducted in developing countries.[11]

Tooth brushing was more among females as compared to the males in the present study but there were no statistically significant differences which was similar to the studies conducted by Hind Al-Johani,[2] Tseveenjav et al.[12] and Tseveenjav et al.[13] Whereas, the gender differences were reported to be highly significant in the studies conducted by Almas et al.,[14] Tada et al.,[15] Al-Omari et al.[16] In the study conducted by Eldarrat,[17] almost 90% of the females reported use of toothbrush, which was a significantly higher proportion (P < 0.001) in comparison to males (75.7%).

Shah et al. from Delhi, India reported that dental caries was more among the rural population compared to urban communities. Multivariate regression analysis showed that dental caries was associated with literacy level, oral hygiene practices, oral health perception and diet.[18] Good oral health outcomes for patients are defined as the primary purpose of dental practice and, therefore, an essential dimension of success. The link between positive patient perceptions of general care and his/her own oral health to practice success needs to be explored.[14]

Several studies have been conducted regarding the frequency of the oral hygiene practices. The most commonly reported frequency for oral hygiene practices has been reported to be 1-2 times a day. Brushing twice daily was reported by 43.6% of the subjects in the present study which was similar to the study conducted by Al-Johani[2] (38.5%). Whereas it was more than the study by Petersen et al.[19] where 33% of participants reported tooth brushing at least twice a day at ages 35-44 years and 21% in the age group of 65-74-year-old. Brushing teeth once daily was reported by majority (54.8%) of the patients in the present study which was similar to the study conducted by Khami et al.[20] (57%) whereas higher than the study conducted by Hind Al-Johani[2] (23.5%). But was quite lesser in comparison to the studies by Almas et al.[14] (81%), Rimondini et al.[21] (91%), and Cortes et al.[22] (100%).

The use of interdental aids was significantly (P value < 0.05) more common among females (24.1%) in comparison to males (10.5%). The studies by Christou et al.[23] and Jackson et al.[24] have proved that by use of interdental cleaning aids, periodontal patients are able to improve clinical outcomes and reduce clinical signs of disease and inflammation.

No regular visit to a dentist was reported by 53.6% of the subjects in the present study which much higher than reported by Steele et al.[25] among British subjects (19-28%) across various age groups. Dental visit within the last 12 months was reported by 45.6% subjects in the present study which was similar to the studies by Behbehani et al. (49%),[26] Peterson et al. (37%),[27] and Al-Hussani et al. (44%).[28] But a better dental attendance than the study conducted by Hind al johani (12.8%).[5]

A perception that there was no need to seek dental care is the commonest reason for avoiding routine dental visit,[13] which was also found in the present study. Dental professionals should give prevention the same status as clinical care so that it is well planned and carefully evaluated.

Majority (66.0%) of the patients in the present study visited a dentist for oral hygiene only if a problem is there. There was a significant (P < 0.05) difference between males and females with regards to the visit for routine oral hygiene maintenance in the present study with 35.8% males and 19.8% females never visiting a dentist for routine oral hygiene maintenance.

Mendoza et al.[29] and Novaes et al.[30] found that gender differences was related to the degree of compliance with supportive periodontal therapy, whereas in the present study there was no gender differences regarding the practice of frequent dental or maintenance visit.

Achieving optimal oral health through preventive efforts is a hallmark of the dental profession. A primary goal of a preventive-oriented dental practice is to encourage patients to practice appropriate oral self-care behavior. When patients are asked to follow an oral self-care regimen, they are being given a target or goal (for example, brush twice a day) and their task is to control or regulate their oral behavior to achieve that objective.[31]

The maintenance of periodontal health requires an informed public and patient. Treatments will fail, and in fact will not ever start, if individuals are not aware of the differences between periodontal health and disease, the significance of these differences and the part they can play in prevention and control. Awareness of the need for the right actions by patients and dental professionals is seen as the key to improving periodontal health.[32]

Current oral hygiene measures, appropriately used and in conjunction with regular professional care, are capable of virtually preventing caries and periodontal disease and maintaining oral health. Tooth brushing and flossing are most commonly used oral hygiene aids, though interdental brushes and wooden sticks can offer advantages in periodontally involved dentitions.[33] Patient's adherence to the periodontal treatment is fundamental to the success of the therapy. Lack of response to the clinician's instructions is influenced by various factors, including gender, age, and psychosocial profile.[34]

CONCLUSION

The efficient control of gingival inflammation obtained by means of supragingival plaque control is fundamental for the success of periodontal treatment. Also, many psychosocial and psychological characteristics influence the patient's adherence to the oral hygiene instructions.[35] The proper perception of oral health could influence adherence by showing the real importance the patient attaches to the treatment,[36] determining a high or low acceptance of the oral hygiene instructions. This is especially important in young patients, who normally present a low adherence to treatment.[37]

The oral hygiene practices are a neglected area of care among the study population leading to the oral health problems. Professional plaque removal and regular follow-up combined with patient oral hygiene instructions can minimize the level of gingival inflammation and swelling.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Azodo CC, Unamatokpa B. Gender difference in oral health perception and practices among Medical House Officers. Russian Open Med J. 2012;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johani HA. Oral Hygiene Practice among Saudi Patients in Jeddah. Cairo Dent J. 2008;24:395–401. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marsh PD. Contemporary perspective on plaque control. Br Dent J. 2012;212:601–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saleh F, Dyer PV. A questionnaire-based survey of patient satisfaction with dental care at two general dental practice locations. Prim Dent Care. 2011;18:53–8. doi: 10.1308/135576111795162857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali NS, Khan M, Butt M, Riaz S. Implications of practices and perception on oral hygiene in patients attending a tertiary care hospital. J Pak Dent Assoc. 2012;1:20–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Axelsson P, Albandar JM, Rams TE. Prevention and control of periodontal diseases in developing and industrialized nations. Periodontol 2000. 2002;29:235–46. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.290112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar N, Gupta N, Kishore J. Kuppuswamy's socio-economic scale: Updating ranged for the year 2012. Indian J Public Health. 2012;56:103–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.96988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolawole KA, Otuyemi OD, Oluwadaisi AM. Assessment of oral health-related quality of life in Nigerian children using the Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ 11-14) Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2011;12:55–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nunez B, Chalmers J, Warren J, Ettinger RL, Qian F. Opinions on the provision of dental care in Iowa nursinghomes. Spec Care Dentist. 2011;31:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2010.00170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen PE, Kandelman D, Arpin S, Ogawa H. Global oral health of older people-call for public health action. Community Dent Health. 2010;27:257–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adair PM, Pine CM, Burnside G, Nicoll AD, Gillett A, Anwar S, et al. Familial and cultural perceptions and beliefs of oral hygiene and dietary practices among ethnically and socio-economical diverse groups. Community Dent Health. 2004;21:102–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tseveenjav B, Vehkalahti M, Murtomaa H. Preventive practice of Mongolian dental students. Eur J Dent Educ. 2002;6:74–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2002.60206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tseveenjav B, Vehkalahti M, Murtomaa H. Oral health and its determinants among Mongolian dentists. Acta Odontol Scand. 2004;62:1–6. doi: 10.1080/00016350310008003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almas K, Al-Hawish A, Al-Khamis W. Oral hygiene practices, smoking habit, and self-perceived oral malodor among dental students. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2003;4:77–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tada A, Hanada N. Sexual differences in oral health behavior and factors associated with oral health behavior in Japanese young adults. Public Health. 2004;118:104–9. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2003.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Omari QD, Hamasha AA. Gender-specific oral health attitudes and behavior among dental students in Jordan. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:107–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eldarrat A, Alkhabuli J, Malik A. The Prevalence of Self-Reported Halitosis and Oral Hygiene Practices among Libyan Students and Office Workers. Libyan J Med. 2008;3:170–6. doi: 10.4176/080527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah N, Sundaram KR. Impact of socio-demographic variables, oral hygiene practices, oral habits and diet on dental caries experience of Indian elderly: A community-based study. Gerodontology. 2004;21:43–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2004.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen PE, Aleksejuniene J, Christensen LB, Eriksen HM, Kalo I. Oral health behavior and attitudes of adults in Lithuania. Acta Odontol Scand. 2000;58:243–8. doi: 10.1080/00016350050217073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khami MR, Virtanen JI, Jafarian M, Murtomaa H. Oral health behaviour and its determinants amongst iranian dental students. Eur J Dent Educ. 2007;11:42–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2007.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rimondini L, Zolfanelli B, Bernardi F, Bez C. Self-preventive oral behavior in an Italian university student population. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:207–11. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028003207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cortes FJ, Nevot C, Ramon JM, Cuenca E. The evolution of dental health in dental students at the university of Barcelona. J Dent Educ. 2002;66:1203–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christou V, Timmerman MF, Van der Velden U, Van der Weijden FA. Comparison of different approaches of interdental oral hygiene: Interdental brushes versus dental floss. J Periodontol. 1998;69:759–64. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.7.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson MA, Kellett M, Worthington HV, Clerehugh V. Comparison of interdental cleaning methods: A randomized controlled trial. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1421–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steele JG, Walls AW, Ayatollahi SM, Murray JJ. Dental attitudes and behaviour among a sample of dentate older adults from three English communities. Br Dent J. 1996;180:131–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behbehani JM, Shah NM. Oral health in Kuwait before the gulf war. Med Princ Pract. 2002;11:36–43. doi: 10.1159/000057777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen PE, Hadi R, Al-Zaabi FS, Hussein JM, Behbehani JM, Skougaard MR, et al. Dental knowledge, attitudes and behavior among Kuwaiti mothers and school teachers. J Pedod. 1990;14:158–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Hussaini R, Al-Kandari M, Hamadi T, Al-Mutawa A, Honkala S, Memon A. Dental health knowledge, attitudes and behaviours among students at the kuwait university health sciences centre. Med Princ Pract. 2003;12:260–5. doi: 10.1159/000072295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendoza AR, Newcomb GM, Nixon KC. Compliance with supportive periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1991;62:731–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.12.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novaes AB, Jr, Novaes AB. Compliance with supportive periodontal therapy. Part 1. Risk of non-compliance in the first 5-year period. J Periodontol. 1999;70:679–82. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blinkhorn AS. Factors affecting the compliance of patients with preventive dental regimens. Int Dent J. 1993;43:294–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramsay DS. Patient compliance with oral hygiene regimens: A behavioural self-regulation analysis with implications for technology. Int Dent J. 2000:304–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choo A, Delac DM, Messer LB. Oral hygiene measures and promotion: Review and considerations. Aust Dent J. 2001;46:166–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2001.tb00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casarin RCV, Ribeiro ELP, Nociti FH, Jr, Sallum EA, Sallum AW, Casati MZ. Self-perception of generalized aggressive periodontitis symptoms and its influence on the compliance with the oral hygiene instructions: A pilot study. Braz J Oral Sci. 2010;9:388–92. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monteiro da Silva AM, Oakley DA, Newman HN, Nohl FS, Lloyd HM. Psychosocial factors and adult onset rapidly progressive periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:789–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Da Silva SR, Castellanos Fernandes RA. Self-perception of oral health status by the elderly. Rev Saude Publica. 2001;35:349–55. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102001000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Novaes AB, Novaes AB, Jr, Moraes N, Campos GM, Grisi MF. Compliance with supportive periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1996;67:213–16. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]