Summary

We describe a simple technique for maintaining highly contractile long-term chicken myogenic cultures on Matrigel, a gel composed of basement membrane components extracted from the Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse tumor. Cultures grown on Matrigel consist of three-dimensional multilayers of cylindrical, contracting myotubes which endure for at least 60 d without myotube detachment. A Matrigel substrate increases the initial plating efficiency but does not effect cell proliferation. Large-scale differentiation in cultures maintained on Matrigel is delayed by 1 to 2 d, compared to cultures grown on gelatin-coated dishes. Long-term maintenance on Matrigel also results in increased expression of the neonatal and adult fast myosin heavy chain isoforms. Culturing of cells on a Matrigel substrate could thus facilitate the study of later events of in vitro myogenesis.

Keywords: myogenesis, basement membrane, Matrigel, myosin isoforms, chicken embryo

Introduction

Primary myogenic cells are routinely cultured on a substrate of gelatin (denatured type I collagen) (13). After plating, cells attach, undergo several rounds of cell division, and eventually withdraw from the cell cycle, expressing muscle-specific proteins and fusing into multinucleated myotubes. These events are similar to what occurs in vivo. Although a gelatin substrate supports in vitro myogenesis, it is not ideal for maintaining long-term myogenic cultures. In myogenic cultures derived from chicken muscle, myotubes begin to detach after 5 to 6 d in culture, when the first spontaneous contractions occur. Myotubes lift individually or as entire sheets, leaving cultures composed primarily of nonmyogenic cells, with some intact myotubes. Hence, developmental and biochemical studies of myogenesis are limited to the first few days in culture, and events that may occur during later development and maturation cannot be examined. For example, during embryogenesis and regeneration of both mammalian and avian fast twitch skeletal muscle there is a transition in fast myosin isoform expression from embryonic to neonatal and then to adult myosin (1,3,7,22,27). In culture, this progression is usually not completed (1,3,6,27) suggesting that conditions or factors needed for maturation are missing in tissue culture. It is also possible, however, that the expression of developmentally advanced myosin isoforms in vitro simply requires more time in culture. This study was undertaken to establish conditions to support long-term primary myogenic cultures.

Myogenic cells have previously been cultured on isolated extracellular matrix components such as fibronectin and laminin (11,16,19,26), as well as within native type I collagen gels (24). In the latter study, myotubes remained attached and contracting for up to 10 d. Laminin selectively enhances mammalian myoblast proliferation and differentiation in vitro (11,16,19,26), but data on culture longevity were not reported. Inasmuch as basement membrane components influence in vitro myogenesis and are present during myogenesis in vivo, eventually surrounding individual muscle fibers (17,23), we examined the capacity of Matrigel, a basement membranelike substrate, to support long-term myogenic cultures. Matrigel, extracted from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm tumors, is a basement membrane gel composed of type IV collagen, laminin, heparan sulfate proteoglycan, and entactin (14). Matrigel, or similar preparations, supports differentiation and affects gene expression in a variety of other systems (4,5,10,12,14,15,20).

We found that myogenic cultures can be maintained on Matrigel for over 60 d. Highly contractile myotubes are arranged in three-dimensional multilayers and remain attached throughout the culture period. Both the neonatal and adult isoforms of myosin heavy chain are expressed.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Primary cultures were prepared from the pectoral muscles of 10-d embryonic chicks. The muscle was excised, finely minced, and dissociated into single cells by trypsin digestion. The crude cell suspension was enriched for myogenic cells by Percoll density centrifugation as previously described (28). Cells were plated at 105 per 35-mm dish, coated with either gelatin or Matrigel. Standard medium consisted of 85% Eagle’s minimum essential medium (MEM, GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), 10% horse serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 5% chicken embryo extract, penicillin and streptomycin at 105 units per liter each, gentamicin at 5 mg per liter, and Fungizone at 2.5 mg per liter. Medium was replaced the first day after plating and every other day thereafter.

Tissue culture dishes (Corning, Corning, NY) were coated with either 100 μl of 2% gelatin (Sigma) or 100 μl of Matrigel (Collaborative Research, Bedford, MA). All procedures with Matrigel were carried out at 0° to 4° C to prevent premature gelation. Matrigel was pipetted onto precooled dishes, spread evenly with a precooled bent Pasteur pipette, and incubated at 37° C for a minimum of 30 min before culturing to allow formation of a stable basal lamina gel. The 2% gelatin solution was warmed to 37° C, pipetted onto dishes at room temperature, and spread and incubated as Matrigel-treated dishes.

Attachment and [3H]thymidine incorporation assays

To assess attachment to the different substrates, cells were plated onto either Matrigel or gelatin-coated, 35-mm dishes and allowed to adhere for 8 h. Nonattached cells were removed by washing 3 times with warm MEM; fresh medium was added, and 10 fields in triplicate cultures were counted by inverted phase microscopy to determine the number of attached cells. Results are expressed as the average number of cells attached per square millimeter.

To assay the effect of a Matrigel substrate on proliferation, the incorporation of [3H]thymidine (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA; specific activity 6.7 Ci/mmol) was measured during the first 7 d of culture. Triplicate cultures were pulsed for 4 h every 24 h in fresh medium containing a final concentration of 1 μCi/ml [3H]thymidine. After labeling, cultures were rinsed 3 times with ice-cold MEM and incubated in 1 ml of ice-cold 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) for at least 1 h. TCA treatment caused partial detachment of the Matrigel from the culture dish, so cells and substrate were routinely collected with a cell scraper and transferred to an Eppendorf tube. The cells and substrate were spun for 5 min (12 000 rpm) in a microfuge. The pellets were rinsed in fresh TCA, spun for 5 min, and then rinsed with phosphate buffered saline. After centrifugation, the pellets were dissolved by incubating in 30 μl NCS™ tissue solubilizer (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) overnight at 37° C. Liquid scintillation counting was performed, using a toluene based scintillant [0.5 g 1,4 bis-2-(4-methyl-5-phenyloxazolyl)-benzene and 5 g 2,5-diphenyloxazole per liter toluene]. Cells cultured on gelatin were processed identically. Matrigel-treated dishes (without cells) were also pulsed and processed to measure nonspecific binding of thymidine to Matrigel.

Myosin isoform assays

The fast myosin heavy chain isoforms expressed in 10-, 20-, and 30-d cultures were determined by indirect immunofluorescent staining with monoclonal antibodies against specific isoforms of chicken fast myosin heavy chain. The antibodies, in the ascites fluid form, were generously provided by Dr. E. Bandman (Department of Food Science and Technology, University of California, Davis, CA), and their specificities have been described (2,6,7). Monoclonal antibody EB165 reacts with both embryonic and adult MHC, AB8 detects the adult isoform only, and 2E9 is neonatal specific. Immunostaining was as previously described (21,28). Cultures were fixed for 30 s in a cold solution of 70% ethanol:formalin:glacial acetic acid, 20:2:1, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in 0.05 M tris, 0.9% NaCl, and 1% normal goat serum to block nonspecific binding. The cells were then incubated with antibodies diluted in blocking solution (EB165 1:1000, 2E9 1:500, and AB8 1:1000) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with fluorescein conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Organon-Teknika Cappel, Downington, PA) diluted 1:50. Myosin-positive cells were also detected with a monoclonal antibody against all forms of sarcomeric myosin [MF20 (1,30)] to assess differentiation and fusion. Staining was as described above, using the hybridoma supernatant at a 1:5 dilution. MF20 was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank [maintained by a contract from NICHD (N01-HD-6-2915)]. To facilitate estimation of differentiation, the nuclei in MF20 reacted cultures were counter-stained with ethidium bromide at a concentration of 2 mg/ml in tris-buffered saline for 5 min at room temperature, followed by three rinses with tris-buffered saline. Cultures were viewed with a Zeiss photomicroscope equipped with phase and epifluorescence optics. Ethidium bromide-stained nuclei were visualized with rhodamine optics. Photomicrographs were taken using fluorescein optics, under which nuclear staining seems dimmer.

Results

Morphology

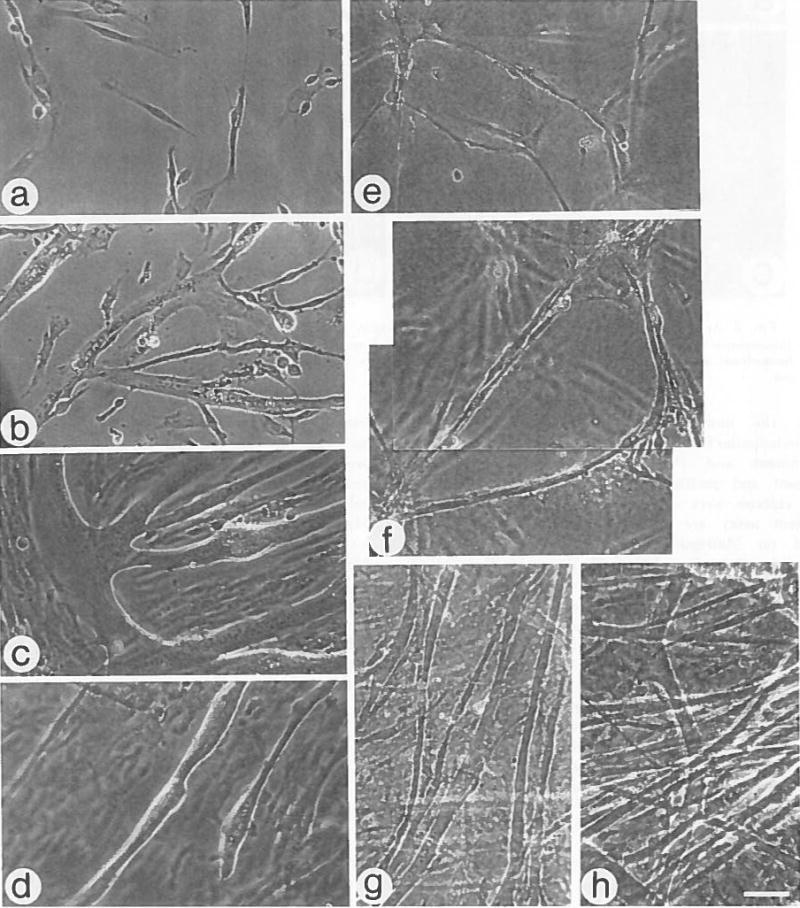

Myoblasts plated on gelatin remain dispersed during the first 24 h of culture (Fig. 1 a), whereas cells plated onto Matrigel migrate into small clusters at different focal levels during this time (Fig. 1 e). These cell clusters are connected by cords of elongated, bipolar cells which form a branched network. By Day 3 in culture, myoblasts maintained on gelatin have fused into flat, branched, multinucleated myotubes (Fig. 1 b). In 3-d Matrigel cultures, cell cords seem similar to myotubes (Fig. 1 f), but myotubes can be discriminated from nondifferentiated cells by the presence of muscle-specific proteins (e.g., myosin, see below). With additional time in culture, numerous contracting myotubes extend between clusters within, above, and below the Matrigel (Fig. 1 g). The cylindrical, prominently cross-striated myotubes in a 2-wk-old culture on Matrigel are arranged in a multilayered, three-dimensional, contracting network (Fig. 1 h). Spontaneous contractions of the myotubes are vigorous and widespread, as is evidenced by undulations of the entire basal lamina gel. The cell density is high, yet these contractile cultures can be maintained for over 60 d without detachment. In contrast, cultures maintained on gelatin for 5 d display intermittent contractions of individual myotubes but not of the entire cell sheet, and detach shortly thereafter (Fig. 1 d), or are overgrown by mononucleated cells. Some myotubes remained attached in gelatin cultures for the 30 d of the study, but consistently fewer than in 30-d Matrigel cultures. Each microscopic field in Matrigel cultures contains many myotubes of varying diameters, whereas myotubes in gelatin cultures are restricted to a few areas where detachment does not occur.

Fig. 1.

Morphology of myogenic cultures maintained on gelatin or Matrigel. a–d, Cultures maintained on gelatin, and e–h cultures maintained on Matrigel, a,e, Day 1; b,f, Day 3; c,g, Day 5; d, Day 11 and h, Day 13. a–c and e–g are live cultures; bar = 48 μm. d,h are fixed cultures; bar = 30 μm. One of several focal levels is shown in Matrigel cultures.

Using morphologic criteria, it is difficult to ascertain when terminal differentiation and fusion first occur in myogenic cultures grown on Matrigel, in contrast to gelatin cultures, in which fusion is obvious. To distinguish between fused, terminally differentiated cells and closely opposed cells in 3-d Matrigel cultures, cultures were stained with MF20, a monoclonal antibody against all sarcomeric myosins. There are fewer terminally differentiated and fused cells in 3-d Matrigel cultures (Fig. 2 c,d), compared to gelatin cultures (Fig. 2 a,b) (29% vs. 69%, respectively). After an additional 2 d in culture, the number of myosin-positive cells and myotubes is similar for both substrates (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Appearance of myosin-positive cells in 3-d gelatin and Matrigel cultures. Phase and corresponding fluorescence micrographs of cells cultured on gelatin (a,b) and on Matrigel (c,d). Cultures were reacted with MF20, a monoclonal antibody specific for all sarcomeric myosins. Arrows indicate ethidium bromide stained nuclei. Bar = 30 μm.

Attachment and [3H]thymidine incorporation

Cell attachment and proliferation in Matrigel- and gelatin-treated cultures were compared. The results of the cell attachment assay are shown in Table 1. More cells attached on Matrigel-treated dishes than on gelatin-treated dishes 8 h after plating. To determine if culturing on Matrigel stimulates myoblast proliferation, incorporation of [3H]thymidine was measured on both Matrigel and gelatin during the first 7 d of culture. Figure 3 shows that during this time the general pattern of [3H]-thymidine incorporation into cells grown on Matrigel is similar to that of cells grown on gelatin, although on Days 4 and 5 there is a significantly higher incorporation in Matrigel cultures. By Day 7, incorporation dropped to baseline levels on Matrigel, whereas cells cultured on gelatin were still proliferating. These proliferating cells were probably nonmyogenic cells that continued dividing in gelatin cultures, because no further increase in myosin-positive cells was seen. Although more cells are attached in Matrigel cultures after 8 h, the similar profile of [3H]thymidine incorporation in Matrigel and gelatin cultures after 24 h suggests that by this time either cell attachment or the number of cells synthesizing DNA is comparable for both substrates.

TABLE 1.

ATTACHMENT OF MYOGENIC CELLS TO GELATIN OR MATRIGEL SUBSTRATES AT 8 H POSTPLATING“

| Substrate | Average Number of Cells Per mm2 | Plating Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin | 118 ± 12 | 59% |

| Matrigel | 145 ± 19 | 72% |

Medium was replaced 8 h after initiation of cultures to remove nonadhered cells. Attached cells were counted in 10 random fields of duplicate cultures.

Fig. 3.

[3H]Thymidine incorporation by myogenic cultures maintained on Matrigel- and gelatin-coated dishes. Cells were exposed to [3H]thymidine for 4 h every 24 h and immediately processed to determine incorporation. CPM represents average values for triplicate plates. Incorporation is significantly higher in Matrigel cultures on Days 4 and 5 (t test, P < 0.05 and P < 0.005, respectively). Standard deviation is smaller than symbol size if deviation bars cannot be seen.

Myosin isoform expression

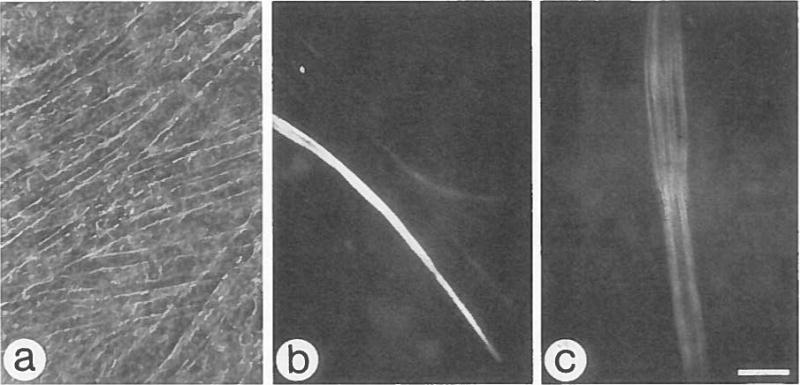

During development of the chicken pectoralis, fast myosin heavy chain progresses from an embryonic to a neonatal and then to an adult isoform (1,3). In primary chick myogenic cultures, the predominant MHC isoform is the embryonic, but the neonatal isoform has been detected in chick myogenic cultures that were highly contractile (6). Inasmuch as Matrigel cultures can be maintained in a contractile state for extended periods, we investigated whether growth on Matrigel supports the neonatal and adult MHC isoform transition. Cultures maintained for 10, 20, and 30 d were fixed and stained with monoclonal antibodies specific for the embryonic and adult fast MHC (EB165), neonatal fast MHC (2E9), and adult fast MHC (AB8). Only EB165 reacts with 10-d Matrigel cultures indicating that the embryonic isoform alone is expressed at this stage; this isoform continues to be expressed in all myotubes in 20- and 30-d Matrigel cultures (data not shown). With additional time in culture, myotubes expressing the neonatal and adult isoforms of MHC appear. The neonatal isoform first becomes detectable in 15-d Matrigel cultures and the adult isoform in 20-d cultures. In 20-d Matrigel cultures, about 25% of the myotubes express the neonatal isoform (Fig. 4 b), and approximately 7% express the adult isoform (Fig. 4 c). After 30 d in culture, myotubes expressing the adult isoform are more frequent (11%), whereas the number of myotubes expressing the neonatal isoform remains constant. In contrast to Matrigel cultures, many of the myotubes present on a gelatin substrate detach between 7 and 10 d of culture. The remaining myotubes in 10-, 20-, and 30-d gelatin cultures are concentrated in small, isolated areas of the culture dish and express the embryonic isoform of MHC. In 20-d gelatin cultures, 17% of the enduring myotubes express the neonatal MHC isoform and none the adult isoform. In 30-d gelatin cultures, the percentage of neonatal-positive myotubes remains constant as on Matrigel, whereas 5% of the myotubes are adult-positive (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Expression of neonatal and adult fast MHC isoforms in 20-d myogenic cultures maintained on Matrigel. a, A representative phase micrograph of a live culture, bar = 48 μm. b, Fluorescence micrograph of a parallel fixed culture stained with monoclonal antibody 2E9, which is specific for neonatal fast MHC. Note positive myotubes out of the focal plane. c, Fluorescence micrograph of culture stained with monoclonal AB8, which is specific for adult fast MHC. Antibody staining shows myotube cross-striations. Bar = 30μm.

Discussion

Culturing of chick myoblasts on Matrigel, a reconstituted basement membrane, results in long-term cultures containing vigorously contracting myotubes which express all three developmental isoforms of fast myosin heavy chain. Matrigel promotes initial cell attachment, but after 24 h in culture, the same level of [3H]thymidine incorporation is observed in Matrigel and gelatin cultures. The overall pattern of [3H]thymidine incorporation is similar for both gelatin and Matrigel substrates during the first 7 d in culture, indicating that Matrigel and gelatin support comparable levels of myoblast proliferation. We also found that myoblasts grown on Matrigel have a 1- to 2-d delay in differentiation and fusion, as shown by the small number of myosin-positive cells and myotubes in a 3-d Matrigel culture compared to a corresponding gelatin culture, suggesting that the basement membrane influences myoblast differentiation. In addition, long-term Matrigel cultures contain myotubes expressing the neonatal and adult fast MHC isoforms. Myotubes sustained on a 1:10 dilution of Matrigel or on a vitrogen gel (native type I collagen) are also more stable and express the neonatal and adult fast MHC isoforms to a greater extent than myotubes on gelatin, but less than Matrigel myotubes (unpublished observations). In comparison, laminin, a component of the basement membrane, has been shown to increase myoblast attachment and proliferation (11,16,19), but effects on culture longevity and MHC isoform transition were not reported.

Vandenburgh et al. (24) and Vandenburgh and Karlisch (25) suggested that increasing mechanical tension during development is important for myogenesis and is missing from tissue culture. They provide mechanical tension during in vitro myogenesis with a three-dimensional collagen gel (24) or with an electronic mechanical cell stimulator (25). The collagen gel supports contracting myotubes for up to 10 d in culture, and the mechanical device stimulates cell fusion and proliferation via stretching of the substrate, resulting in long, parallel arrays of myotubes. Our results indicate that a Matrigel substratum also provides structural support and the necessary tension to maintain long-term cultures of contracting, cylindrical myotubes with minimal branching, compared to gelatin cultures.

A correlation between contractility and neonatal fast MHC isoform expression in chick myogenic cultures was described by Cerny and Bandman (6). Our study demonstrates that Matrigel provides reproducible conditions for contraction and expression of the neonatal isoform in avian myogenic cultures. Matrigel also supports expression of the adult fast MHC isoform, which has not been detected previously in chicken myogenic cultures. Myotubes expressing the adult isoform were detected at a very low frequency in quail cultures (18, P. Merrifield, personal communication) as well as in cultures of regenerating adult mouse myofibers cocultured with embryonic mouse spinal cord (9). In the latter study, adult isoform expression was independent of nerve-induced contractions, and a trophic effect of the spinal cord tissue on adult MHC expression was suggested. Our studies indicate that adult fast MHC can be expressed in chicken myogenic cultures in the absence of nerve. Regardless, we cannot eliminate the possibility that, in addition to providing structural support, Matrigel contains trophic factors important for myoblast differentiation and maturation. Alternatively, Matrigel could sequester such factors from the medium and store them in a manner analogous to the storage of fibroblast growth factor in the extracellular matrix of mouse skeletal muscle (8,29).

We did not observe any myotube detachment in long-term Matrigel cultures. Nor did we detect any increase in the frequency of differentiated cells (i.e. cells positive for MF20) in long-term Matrigel cultures, suggesting that no new myotubes are formed in the later cultures. Also, we did not observe any foci of terminally differentiated mononucleated myoblasts which could potentially form new myotubes or fuse into preexisting myotubes and specifically contribute to the expression of the adult myosin isoform. We thus suggest that the myotubes expressing adult myosin in Matrigel cultures are aged myotubes rather than lately formed myotubes.

In summary, this study demonstrates that routine culturing of myogenic cells on a basement membranelike substrate provides a simple and effective means of supporting long-term myogenic cultures. It therefore offers a cell culture system in which later events of myogenesis can be studied.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Everett Bandman for his generous gift of monoclonal antibodies EB165, 2E9, and AB8, and John C. Dennis for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants to Z. Y. -R. from the American Heart Association Washington Affiliate, the University of Washington Graduate School Research Fund, and the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (AR39677). R. S. H. was supported by a Predoctoral Developmental Biology Training Grant from the National Institutes of Health (HD07183-10).

Footnotes

Note Added in Proof

Strohman et al. (31) have recently reported on the expression of neonatal and adult isoforms of fast myosin heavy chain in chicken myogenic cultures maintained on flexible membranes.

References

- 1.Bader D, Masaki T, Fischman DA. Immunochemical analysis of myosin heavy chain during avian myogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:763–770. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandman E. Myosin isoenzyme transitions in muscle development, maturation, and disease. Int Rev Cytol. 1985;97:97–131. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandman E, Matsuda R, Strohman RC. Developmental appearance of myosin heavy and light chain isoforms in vivo and in vitro in chicken skeletal muscle. Dev Biol. 1982;93:508–518. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Aggeler J, Ram TG, et al. Functional differentiation and alveolar morphogenesis of primary mammary cultures on reconstituted basement membrane. Development (Camb) 1989;105:223–235. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Ze’ev A, Robinson GS, Bucher NLR, et al. Cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions differentially regulate the expression of hepatic and cytoskeletal genes in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2161–2165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerny LC, Bandman E. Contractile activity is required for the expression of neonatal myosin heavy chain in embryonic chick pectoral muscle cultures. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:2153–2161. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerny LC, Bandman E. Expression of myosin heavy chain isoforms in regenerating myotubes of innervated and denervated chicken pectoral muscle. Dev Biol. 1987;119:350–362. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimario J, Buffinger N, Yamada S, et al. Fibroblast growth factor in the extracellular matrix of dystrophic (mdx) mouse muscle. Science. 1989;244:688–690. doi: 10.1126/science.2717945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ecob-Prince MS, Jenkison M, Butler-Browne GS, et al. Neonatal and adult myosin heavy chain isoforms in a nerve muscle culture system. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:995–1005. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.3.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emonard H, Grimaud JA, Nusgens B, et al. Reconstituted basement-membrane matrix modulates fibroblast activities in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 1987;133:95–102. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041330112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster RF, Thompson JM, Kaufman SJ. A laminin substrate promotes myogenesis in rat skeletal muscle cultures: analysis of replication and development using antidesmin and anti-BrdUrd monoclonal antibodies. Dev Biol. 1987;122:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90327-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hadley MA, Byers SW, Suarez-Quian CA, et al. Extracellular matrix regulates Sertoli cell differentiation, testicular cord formation, and germ cell development in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:1511–1522. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauschka SD, Konigsberg IR. The influence of collagen on the development of muscle colonies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1966;55:119–126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleinman HK, McGarvey ML, Hassell JR, et al. Basement membrane complexes with biological activity. Biochemistry. 1986;25:312–318. doi: 10.1021/bi00350a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubota Y, Kleinman HK, Martin GR, et al. Role of laminin and basement membrane in the morphological differentiation of human endothelial cells into capillary-like structures. J Cell Biol. 1989;107:1589–1598. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kühl U, Öcalan M, Timpl R, et al. Role of laminin and fibronectin in selecting myogenic versus fibrogenic cells from skeletal muscle cells in vitro. Dev Biol. 1986;117:628–635. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayne R, Swasdison S, Sanderson RD, et al. Extracellular matrix, fibroblasts, and the development of skeletal muscle. In: Kedes LH, Stockdale FE, editors. Cell and Molecular Biology of Muscle Development. New York: Alan R Liss; 1989. pp. 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrifield PA, Sutherland WM, Konigsberg IR. Co-expression of multiple, adult myosin heavy chains in embryonic quail pectoral muscle and cultured myotubes. In: Kedes LH, Stockdale FE, editors. Cell and Molecular Biology of Muscle Development. New York: Alan R Liss; 1989. pp. 481–490. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Öcalan M, Goodman SL, Kühl U, et al. Laminin alters cell shape and stimulates motility and proliferation of murine skeletal myoblasts. Dev Biol. 1988;125:158–167. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Opas M. Expression of the differentiated phenotype by epithelial cells in vitro is regulated by both biochemistry and mechanics of the substratum. Dev Biol. 1989;131:281–293. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(89)80001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson MM, Quinn LS, Nameroff M. BB creatine kinase and myogenic differentiation: immunocytochemical identification of a distinct precursor compartment in the chicken skeletal myogenic lineage. Differentiation. 1984;26:112–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1984.tb01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saad AD, Obinata T, Fischman DA. Immunochemical analysis of protein isoforms in thick myofilaments of regenerating skeletal muscle. Dev Biol. 1987;119:336–349. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solursh M, Jensen KL. The accumulation of basement membrane components during the onset of chondrogenesis and myogenesis in the chick wing bud. Development (Camb) 1988;104:41–49. doi: 10.1242/dev.104.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vandenburgh HH, Karlisch P, Farr L. Maintenance of highly contractile tissue-cultured avian skeletal myotubes in collagen gel. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1988;24:166–172. doi: 10.1007/BF02623542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vandenburgh HH, Karlisch P. Longitudinal growth of skeletal myotubes in vitro in a new horizontal mechanical cell stimulator. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1989;25:607–616. doi: 10.1007/BF02623630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von der Mark K, Öcalan M. Antagonistic effects of laminin and fibronectin on the expression of the myogenic phenotype. Differentiation. 1989;40:150–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1989.tb00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whalen RG, Sell SM, Butler-Browne GS, et al. Three myosin heavy chain isozymes appear sequentially in rat muscle development. Nature. 1981;292:805–809. doi: 10.1038/292805a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Nameroff M. Skeletal muscle cell populations: Separation and partial characterization of fibroblast-like cells from embryonic tissue using density gradient centrifugation. Histochemistry. 1987;87:27–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00518721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamada S, Buffinger N, DiMario J, et al. Fibroblast growth factor is stored in fiber extracellular matrix and plays a role in regulating muscle hypertrophy. Med Sci Sports Exercise. 1989;21:S173–S180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zadeh BJ, González-Sánchez A, Fischman DA, et al. Myosin heavy chain expression in embryonic cardiac cell cultures. Dev Biol. 1986;115:204–214. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strohman RC, Bayne E, Spector D, et al. Myogenesis and histogenesis of skeletal muscle on flexible membranes in vitro. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1990;26:201–208. doi: 10.1007/BF02624113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]