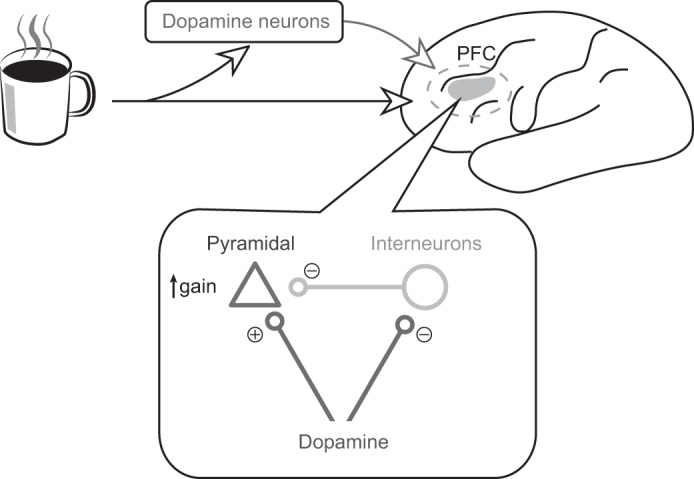

Fig. 1.

How does the brain represent salient stimuli (e.g., a coffee mug in the morning) to elicit the appropriate response (e.g., drinking the coffee)? Neurons in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) maintain relevant information in working memory, in a process thought to rely on dopamine release. But what is the mechanism of dopamine's action in PFC? In a recent paper, Jacob et al. (2013) recorded from PFC neurons while monkeys performed a simple working-memory task. During the recording, the authors locally applied either dopamine or saline and measured how these manipulations affected PFC responses. They found that dopamine decreased stimulus-evoked activity in putative interneurons (circle), while increasing the gain of activity in putative pyramidal neurons (triangle). Such a gain increase is consistent with the popular “gating” model of dopamine function, which posits that dopamine enhances PFC responses to relevant input, allowing PFC neurons to stably represent important information without distraction from irrelevant stimuli.