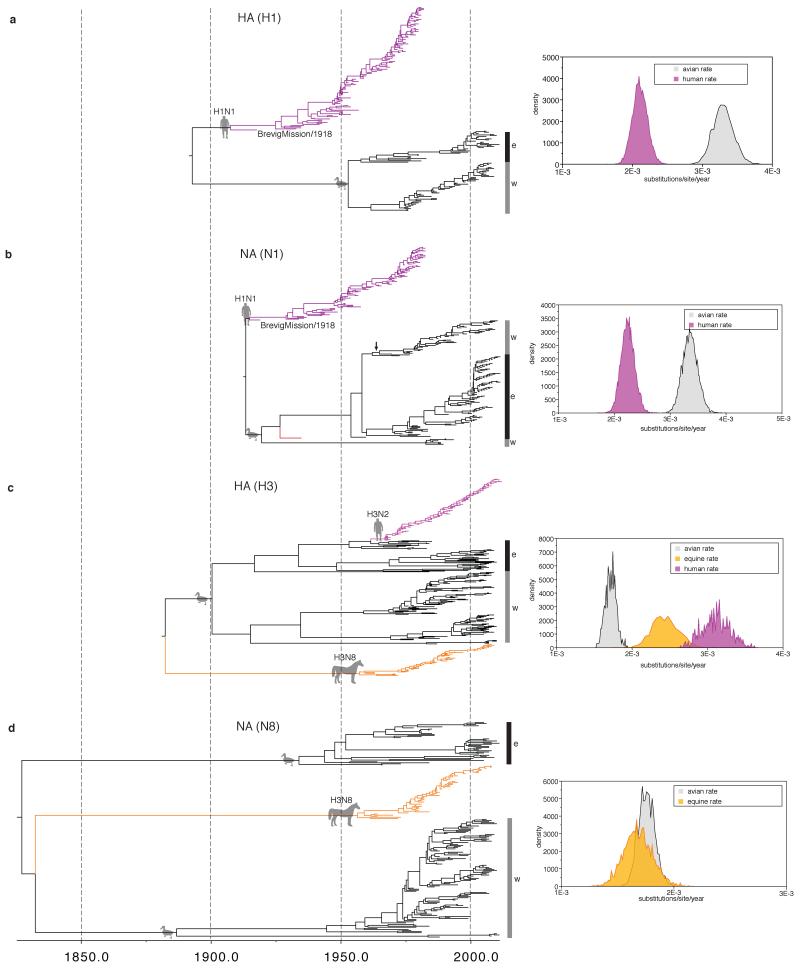

Extended Data Figure 6. HSLC results for H1, N1, H3, and N8.

a-d, respectively: MCC trees inferred under the HSLC model and host-specific rate distributions (to the right of each tree). Trees are drawn to the same scale, with branch lengths in years. Eastern and Western Hemisphere AIV lineages are highlighted with black and gray vertical bars, respectively. Fully resolved trees including posterior probabilities for each node and 95% CIs on node dates are depicted in Fig. S1 i through l. These results suggest an avian origin of the H1 HA and N1 NA of the 1918 human pandemic virus, sometime after the human/avian MRCA in ~1893 for HA and the human/avian MRCA in ~1914 for NA. For H1, the available sample of AIV sequences coalesces in ~1952. Hence, the H1 Western and Eastern Hemisphere lineages were established very recently compared to the internal genes (Fig. 2). This means that current sampling can provide no information about the geographic origin of the HA gene of the 1918 virus. Similarly, for N1, a deep Western Hemisphere lineage shares an MRCA with the Eastern Hemisphere lineage in ~1919 (with a subsequent east-to-west dispersal in the early 1960s, indicated by a vertical arrow). Again, these data offer no insights into the geographical origin of the 1918 pandemic virus’s NA gene since the 1918 sequence is not nested within either a Western or Eastern hemisphere AIV clade as with the internal genes. If archival AIV sequences from closer to 1918 could be recovered they might resolve these geographical questions. For H3 and N8 distinct equine lineages are apparent; however, when and where they crossed from the AIV reservoir remains unclear (see the Supplementary Information for additional discussion).