Abstract

An isotope dilution mass spectrometry method has been developed for the simultaneous measurement of picolinoyl derivatives of testosterone (T), dihydrotestosterone (DHT), 17β-estradiol (E2), and 5α-androstan-3α,17β-diol (3α-diol) in rat intratesticular fluid. The method uses reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Following derivatization of 10-μL samples of testicular fluid with picolinoyl chloride hydrochloride, the samples were purified by solid phase extraction before analysis. The accuracy of the method was satisfactory for the 4 analytes at 3 concentrations, and both inter- and intraday reproducibility were satisfactory for T, DHT, and E2. Measurements of intratesticular T concentrations in a group of 8 untreated adult rats by this method correlated well with measurements of the same samples by radioimmunoassay. As in men, there was considerable rat-to-rat variability in T concentration, despite the fact that the rats were inbred. Although its levels were more than an order of magnitude lower than those of T, DHT was measured reliably in all 8 intratesticular fluid samples. DHT concentration also varied from rat to rat and was highly correlated with T levels. The levels of E2 and 3α-diol also were measurable. The availability of a sensitive method by which to measure steroids accurately and rapidly in the small volumes of intratesticular fluid obtainable from individual rats will make it possible to examine the effects, over time, of such perturbations as hormone and drug administration and environmental toxicant exposures on the intratesticular hormonal environment of exposed individual males and thereby to begin to understand differences in response between individuals.

Keywords: Androgen, steroidogenesis, testis

Androgens and estrogens have been shown to be integrally involved in regulating mammalian spermatogenesis. Testosterone (T, 17β-hydroxyandrost-4-en-3-one), the predominant steroid within the testes of rats as well as humans (Turner et al, 1984; Zhao et al, 2004), is required for the maintenance of spermatogenesis (Zirkin et al, 1989; Awoniyi et al, 1992; McLachlan et al, 1996; Jarow and Zirkin, 2005; Ruwanpura et al, 2010) and for its restoration after experimentally induced azoospermia (Awoniyi et al, 1989a,b). Because androgen action in the testis is mediated through androgen receptors (Roberts and Zirkin, 1991; McLachlan et al, 1996; Holdcraft and Braun, 2004), 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT, 5α-androstan-17β-ol-3-one) would be expected to maintain spermatogenesis more effectively than T because of its greater affinity for, and slower rate of dissociation from, the androgen receptor (Chen et al, 1994; McLachlan et al, 1996). Indeed, we have shown experimentally in rats that, as predicted, far lower average concentrations of DHT than of T will maintain spermatogenesis quantitatively (Chen et al, 1994). 17β-Estradiol (E2, 1,3,5-estratriene-3,17β-diol) also has been reported to have direct effects on spermatogenesis in addition to effects that are mediated via the hypothalamic-pituitary axis (Holdcraft and Braun, 2004; Allan et al, 2010).

In men, intratesticular steroid levels vary considerably from individual to individual (Jarow et al, 2001). Additionally, some, but not all men become azoospermic or severely oligospermic in response to T-based contraceptive formulations (World Health Organization, 1996; Page et al, 2008), and the success of hormonally induced azoospermia has been shown to vary with ethnic origin. Thus, in trials using T-alone regimens, Asian men demonstrated far higher attainment of azoospermia than their non-Asian counterparts (Gu et al, 2003; Gui et al, 2004). The reasons for differences between different men in intratesticular T levels and in their responsiveness to administered androgens remain uncertain. With regard to the latter, one possibility is that, in response to hormone administration, intratesticular hormone levels (T, E2, DHT, weak androgens) differ in different men. Although this could be determined in men, invasive procedures would be required to do so. Rats often are used as a model for the human. If there were rat-to-rat differences in intratesticular steroids and nonuniform response to androgen administration as in the human, perhaps the rat could be used to understand individual differences in men.

The availability of a rapid, sensitive method to measure steroids of potential relevance to spermatogenesis in the low fluid volumes obtainable from the rat testis would be invaluable in comparing individual rats and their responses to hormone administration, and particularly so if the method made it possible to measure intratesticular steroids over time in the low fluid volumes obtainable by testicular aspiration. In a previous study, we described a method by which to analyze 20-μL samples of human testicular fluid (Zhao et al, 2004). A major goal of the current study was to reduce sample size to 10 μL so it would be feasible to measure steroids in the small volumes obtainable from testicular aspirates. In the studies herein, we describe a simple, rapid, and sensitive isotope dilution mass spectrometry method for the simultaneous measurement of picolinoyl derivatives of T, DHT, E2, and 5α-androstan-3α,17β-diol (3α-diol) in small (<10 μL) fluid volumes of intratesticular fluid from individual adult rats. Picolinoyl derivatization, which adds picolinoyl groups at C-17 or C-3 hydroxyl groups for the 4 steroids studied, has been used successfully to measure estrone and E2 in human serum and corticosteroids in human saliva and urine (Yamashita et al, 2007a,b; 2008). We applied picolinoyl derivatization to the analysis of T, DHT, E2, and 3α–diol using commercially available stable isotope internal standards. This approach resulted in a sensitive and specific isotope dilution–high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)–tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) method for quantification of the 4 steroids of interest in small volumes of testicular fluid obtained from untreated, individual adult rats. Additionally, we replaced the nonspecific internal standard that we had used previously (dimethyl benzoyl phenyl urea) with stable isotope internal standards for each of the 4 analytes, thus increasing measurement accuracy during sample extraction, clean-up, and analysis.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

T, DHT, and 3α-diol were obtained from Steraloids Inc (Newport, Rhode Island). Tri-deuterium–labeled DHT (DHT-D3, DHT-16,16,17-D3), E2-D3, and 3α-diol-D3 were obtained from C/D/N Isotopes (Pointe-Claire, Quebec, Canada). E2, T-D3, anhydrous acetonitrile, anhydrous pyridine, and acetic acid were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, Missouri). All other solvents were obtained from Honeywell Burdick and Jackson (Muskegon, Michigan). Bond Elut C18 columns were obtained from Varian (Walnut Creek, California). Picolinoyl chloride hydrochloride was obtained from TCI America (Portland, Oregon). All glassware was deactivated before use with Sylon CT (Supelco, Bellafonte, Pennsylvania).

Preparation of Standards

Stock solutions of T, T-D3, DHT, DHT-D3, E2, E2-D3, 3α-diol, and 3α-diol-D3 were prepared by weighing and diluting each standard to a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL in methanol/acetonitrile (50/50, vol/vol). The compounds were stable for at least 6 months when stored in deactivated glass vials at −20°C.

Study Animals

Testicular fluid samples were obtained from young adult (3–4 months old) Brown Norway rats. The rats were decapitated by guillotine in accordance with protocols approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The testes were rapidly excised and weighed. Each testis was decapsulated and plunged through a 3-mL syringe into a centrifuge tube. The tube was spun at 7000 × g for 15 minutes to separate the tissue from the intratesticular fluid (Turner et al, 1984). The fluid was collected and immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. The time from decapitation to the collection of testicular fluid was less than 30 minutes. Total T concentration in thawed intratesticular samples was determined by radioimmunoassay (RIA; Schanbacher and Ewing, 1975) for comparison with T concentration as analyzed by HPLC-MS/MS.

HPLC-MS/MS Analysis

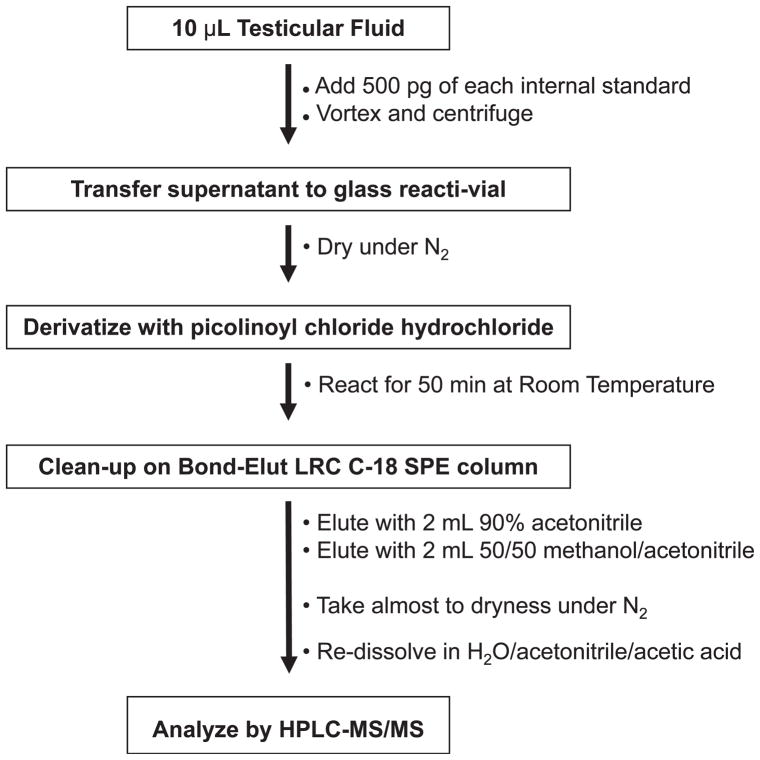

A schematic outline of the HPLC-MS/MS method is presented in Figure 1. Samples were thawed at room temperature for 5 minutes. Testicular fluid (10 μL) was added to 500 μL of methanol/acetonitrile (50/50, vol/vol) containing 500 pg of each of the 4 deuterated internal standards. The samples were centrifuged for 3 minutes at 9000 ×g, and the supernatant was transferred to a glass reacti-vial. The samples were taken almost to dryness under N2 and then derivatized with picolinoyl chloride hydrochloride following a previously published method (Yamashita et al, 2007a) with slight modification. Vials were first were capped with septa and flushed with argon. After the addition of 50 μL of anhydrous pyridine to each vial, vials were vortexed, and 100 μL of a 40 mg/mL solution of picolinoyl chloride hydrochloride in anhydrous acetonitrile was added. The samples were then heated for 5 minutes at 40°C and allowed to react at room temperature for an additional 45 minutes. The reaction was stopped by adding 2 mL of water to each vial. Samples were subjected to solid phase extraction. Bond Elut C18 columns (200 mg) were preconditioned with 4 mL of acetonitrile followed by 4 mL of water. The reaction mixture was loaded onto the column and washed with 3 mL of water and 4 mL of H2O/acetonitrile/glacial acetic acid (69/30/1, vol/vol/vol). The derivatized products were then eluted into a reacti-vial with 2 mL of acetonitrile/H2O (90/10, vol/vol) followed by 2 mL of methanol/acetonitrile (50/50, vol/vol). After taking samples almost to dryness under N2, the samples were reconstituted in 50 μL of H2O/methanol/glacial acetic acid (49/50/1, vol/vol/vol) for injection.

Figure 1.

Analytical scheme for analysis of testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, 17β-estradiol, and 5α-androstan-3α,17β-diol in rat testicular fluid. HPLC-MS/MS indicates high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry; SPE, solid phase extraction.

The analysis was carried out on a Thermo-Finnigan TSQ Quantum Ultra triple quadrupole mass spectrometer coupled to a Thermo-Finnigan Surveyor Plus HPLC and auto injector (Thermo Electron Corporation, San Jose, California). Samples were maintained at 10°C before injection of 10-μL aliquots. Chromatographic separation was carried out at 35°C at a flow rate of 70 μL/min on a 1×150×3-μm X-Terra C18 HPLC column (Waters Corp, Milford, Massachusetts). Mobile phase compositions were (vol/vol/vol) water/acetonitrile/acetic acid (A, 95/5/0.1) and acetonitrile/acetic acid (B, 100/0.1). The initial mobile phase composition of 45% B was ramped to 80% B over 19 minutes, held at 80% B until 24 minutes, and then ramped to 95% B for 1 minute before re-equilibration to 45% B for 6 minutes. Column flow was diverted away from the ElectroSpray Ionization (ESI) Ion Source, except for the time period from 7 to 24 minutes. HPLC retention times for the 8 compounds are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

HPLC-MS/MS parameters for the determination of T, DHT, E2, and 3α-diol in testicular fluid

| Analyte | Retention Time, min | Precursor ion, m/z | Product Ions, m/z | Collision Energy, eV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | 11.22 | 394.1 (M+H)+ | 124.2 + 271.2 | 19 |

| T-D3 | 11.18 | 397.1 (M+H)+ | 125.2 + 274.2 | 19 |

| DHT | 15.13 | 396.1 (M+H)+ | 124.2 + 255.2 | 21 |

| DHT-D3 | 15.05 | 399.1 (M+H)+ | 125.2 + 258.2 | 21 |

| E2 | 15.67 | 483.1 (M+H)+ | 360.2 | 17 |

| E2-D3 | 15.53 | 486.1 (M+H)+ | 363.2 | 17 |

| 3α-Diol | 21.19 | 503.1 (M+H)+ | 380.2 | 13 |

| 3α-Diol-D3 | 21.11 | 506.1 (M+H)+ | 383.2 | 13 |

Abbreviations: 3α-diol, 5α-androstan-3α,17β-diol; D3, tri-deuterium–labeled (16,16,17-D3); DHT, dihydrotestosterone; E2, 17β-estradiol; HPLC-MS/MS, high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry; T, testosterone.

Positive ESI-MS/MS was conducted with the capillary temperature set at 280°C, the sheath gas at 50 arbitrary units, and the spray voltage at 5 kV. MS/MS transitions and collision energies are listed in Table 1. Selected reaction monitoring chromatograms for a typical testicular fluid sample area are given in Figure 1.

Detection limits were determined to be 0.4 pg for T, 0.4 pg for DHT, 0.4 pg for E2, and 1.5 pg for 3α-diol. Linear 10-point calibration curves (all r2 > .99) were generated by duplicate 10-μL injections of T-D3, DHT-D3, E2–D3, and 3α-diol-D3, all at 500 pg/50 μL with varying concentrations of the nonlabeled compound (0, 2.0, 3.9, 7.8, 23.5, 62.5, 125, 250, 500, and 2000 pg/50 μL). Calibration curves were computed using the ratio of the peak area of the analyte and its individual internal standard by using a weighted 1/x linear regression analysis. The apparent recovery of the method, which takes into account losses during cleanup and matrix suppression in the ESI source, was quantitative for all metabolites measured. Limits of determination were determined for each compound: 0.20 ng/mL for T, 0.20 ng/mL for DHT, 0.20 ng/mL for E2, and 0.78 ng/mL for 3α-diol.

Results

Accuracy

To determine the accuracy of the method, intratesticular fluid (700 μL) was obtained from the testes of each of 8 untreated rats and pooled. The sample was charcoal stripped for 24 hours at 50°C with shaking on an Eppendorf Thermomixer (Eppendorf North America, Hauppauge, New York). After filtration through a 0.2-μL membrane, the sample was divided into 10-μL aliquots. Five samples were spiked at each of 4 levels (0, 0.78, 6.25, or 250 ng/mL) of T, DHT, E2, and 3α-diol, and at 50 ng/mL for each of the 4 deuterated internal standards: T-D3, DHT-D3, E2-D3, and 3α-diol-D3. The results are shown in Table 2. Levels for T, DHT, E2, and 3α-diol were below the limit of determination for samples to which only internal standards were added. Accuracy for the method was within the acceptable range of 80%–120% for all 4 analytes at the 3 levels tested.

Table 2.

Accuracy (as a percentage of spiked level) for the determination of T, DHT, E2, and 3α-diol in stripped rat testicular fluid at 3 spiked concentrationsa

| T

|

DHT

|

E2

|

3α-Diol

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiked Level, ng/mL | Measured Level, ng/mL | Accuracy, % | Measured Level, ng/mL | Accuracy, % | Measured Level, ng/mL | Accuracy, % | Measured Level, ng/mL | Accuracy, % |

| 0.00 | <0.20 | . . . | <0.20 | . . . | <0.20 | . . . | <0.78 | . . . |

| 0.78 | 0.68 (±0.18) | 87 | 0.66 (±0.11) | 84 | 0.74 (±0.07) | 95 | 0.72 (±0.45) | 93 |

| 6.25 | 5.7 (±0.24) | 91 | 4.98 (±0.40) | 80 | 7.52 (±1.36) | 120 | 5.90 (±0.52) | 105 |

| 250 | 265 (±11.6) | 106 | 201 (±9.1) | 80 | 260 (±9.0) | 104 | 262 (±11.4) | 105 |

Abbreviations: 3α-diol, 5α-androstan-3α,17β-diol; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; E2, 17β-estradiol; T, testosterone.

Values presented are x̄ (±SD) for 5 determinations at each spiking level.

Reproducibility

The reproducibility of the method was examined by pooling testicular fluid. The fluid was divided into 15, 10-μL aliquots in Eppendorf tubes. After the addition of E2 to a concentration of ~5 ng/mL to bring that analyte to a measurable level, the samples were frozen at −80°C. On 3 subsequent days, 5 samples were thawed for the determination of intra- and interday variability. The results are presented in Table 3. Intra- and interday coefficients of variation were less than 15% for T, DHT, and E2. The 3α-diol measurements were more variable.

Table 3.

Reproducibility (% coefficient of variation) for the determination of T, DHT, E2, and 3α-diol in pooled rat testicular fluida

| Day 1

|

Day 2

|

Day 3

|

Between-Day

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analyte | Average Level, ng/mL | CV, % | Average Level, ng/mL | CV, % | Average Level, ng/mL | CV, % | Average Level, ng/mL | CV, % |

| T | 102 (±2.5) | 2.4 | 101 (±3.1) | 3.0 | 100 (±2.5) | 2.5 | 101 (±2.7) | 2.7 |

| DHT | 2.1 (±0.2) | 9.7 | 2.1 (±0.1) | 4.3 | 2.6 (±0.2) | 5.9 | 2.2 (±0.3) | 12.6 |

| E2 | 5.5 (±0.4) | 6.4 | 4.9 (±0.4) | 8.8 | 5.0 (±0.3) | 5.3 | 5.2 (±0.4) | 8.4 |

| 3α-Diol | 15.0 (±2.0) | 13.6 | 7.7 (±0.6) | 7.2 | 8.9 (±1.5) | 17.4 | 10.6 (±3.6) | 34.1 |

Abbreviations: 3α-diol, 5α-androstan-3α,17β-diol; CV, coefficient of variation; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; E2, 17β-estradiol; T, testosterone.

Values presented are x̄ (±SD) for 6 determinations at each spiking level on 3 consecutive days.

Stability

To observe whether conversion from one steroid to another might occur after the samples were collected, approximately 20 μL of testicular fluid obtained from each of the 8 rats was allowed to thaw at room temperature for 5 minutes. A 10-μL aliquot from each sample was immediately worked up and analyzed as described above. The remaining 10-μL aliquot per sample was left at room temperature for 30 minutes before analysis. The latter resulted in an average decrease of 30% for T and 3α-diol levels, a 10% decrease in DHT, and a 6% decrease in E2. Although these results were not statistically significant at the 95% confidence interval, they are analytically significant, and draw attention to the fact that repeated freeze-thaw cycles for samples, and even short times at room temperature, could alter the steroid profile of the samples.

Analysis of Intratesticular Steroids by HPLC-MS/MS

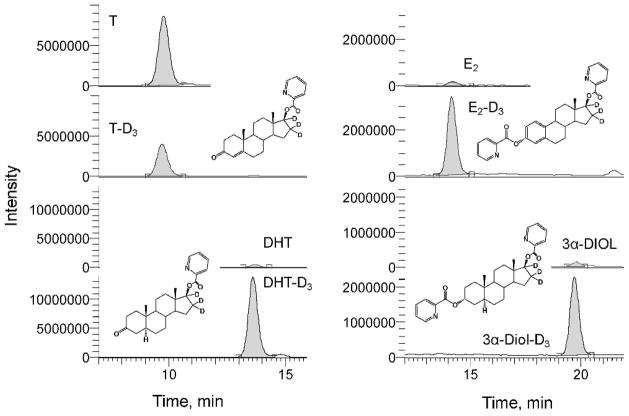

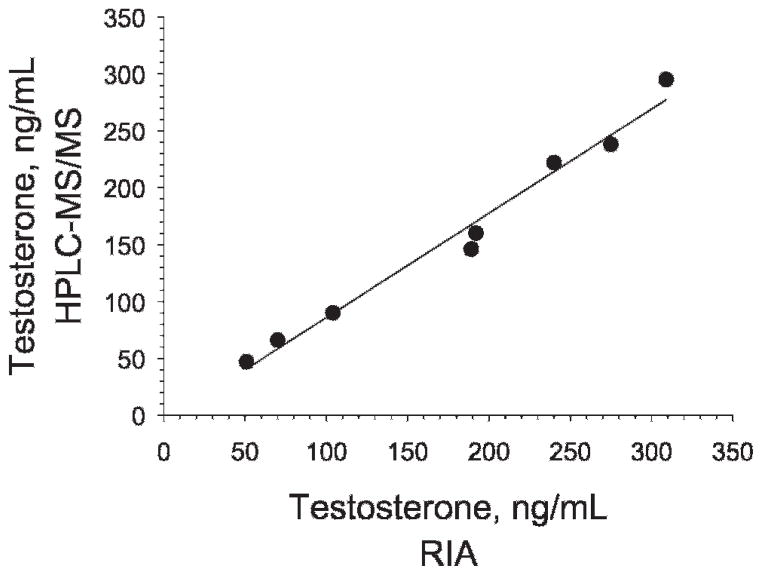

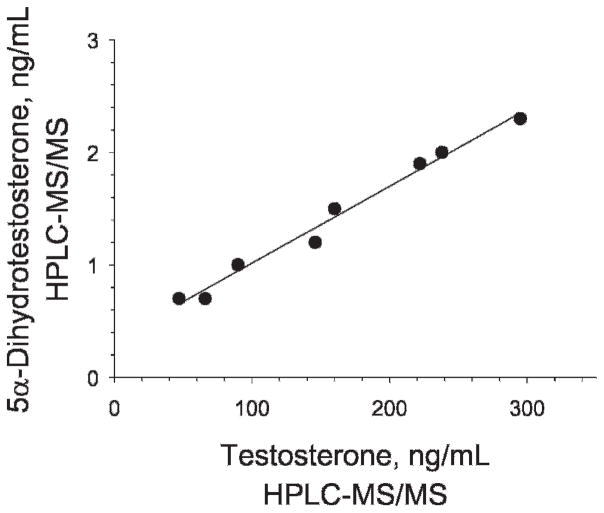

The intratesticular concentrations of T, DHT, E2, and 3α-diol, as determined by HPLC-MS/MS, are shown for each of the 8 rats in Table 4. A representative chromatogram from a rat testicular fluid sample is shown in Figure 2. Interestingly, the concentrations of T were highly variable from rat to rat, ranging from 47 to 295 ng/mL, with x̄ ± SD of 158 ± 31. The levels of T in the same samples were independently determined by RIA (Schanbacher and Ewing, 1975). The T range obtained by RIA, 51–309 ng/mL, was similar to the range obtained by HPLC-MS/MS. Additionally, as seen in Table 4 and depicted in Figure 3, the results obtained for the intratesticular T concentrations in individual rats by the 2 methods showed excellent correlation (r2 > .98). Using RIA, DHT, E2, and 3α-diol levels could not be measured reliably in the 8 intratesticular samples (results not shown). Using HPLC-MS/MS, however, the DHT concentration was measurable in all 8 samples, ranging from 0.7 to 2.3 ng/mL with a mean of 1.4 ± 0.2. Figure 4 shows that T and DHT levels were highly correlated within the testes of individual rats. E2 could be measured reliably as well, although in 3 of the 8 samples, and ranged from 1.3 to 2.7 ng/mL. Likewise, 3α-diol was measurable in 4 of the 8 samples, ranging from 1.0 to 2.9 ng/mL.

Table 4.

T, DHT, E2, and 3α-diol concentrations in the testicular fluid of 8 control rats

| T

|

DHT

|

E2

|

3α-Diol

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | HPLC-MS/MS, ng/mL | RIA, ng/mL | HPLC-MS/MS, ng/mL | HPLC-MS/MS, ng/mL | HPLC-MS/MS, ng/mL |

| 1 | 47 | 51 | 0.70 | <0.20 | <0.78 |

| 2 | 66 | 70 | 0.73 | <0.20 | 1.05 |

| 3 | 90 | 104 | 1.03 | 1.29 | <0.78 |

| 4 | 160 | 192 | 1.47 | 1.48 | <0.78 |

| 5 | 238 | 275 | 2.03 | <0.20 | 2.87 |

| 6 | 295 | 309 | 2.27 | <0.20 | 1.25 |

| 7 | 222 | 240 | 1.90 | 2.67 | 1.12 |

| 8 | 146 | 189 | 1.20 | <0.20 | <0.78 |

| x̄ | 158 | 179 | 1.41 | 0.80 | 1.18 |

Abbreviations: 3α-diol, 5α-androstan-3α,17β-diol; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; E2, 17β-estradiol; HPLC-MS/MS, high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry; RIA, radioimmunoassay; T, testosterone.

Figure 2.

High-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry mass chromatograms for the analysis of picolinoyl derivatives of testosterone (T), dihydrotestosterone (DHT), 17β-estradiol (E2), and 5α-androstan-3α,17β-diol (3α-diol) in testicular fluid. Structures are shown only for deuterium-labeled compounds. D3 indicates tri-deuterium–labeled (16,16,17-D3).

Figure 3.

Correlation (r2 = .98) for the analysis of testosterone by high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) and radioimmunoassay (RIA). The slope of the correlation curve is y = 1.07 + 9.37.

Figure 4.

Correlation of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone in the intratesticular fluid of individual rats. HPLC-MS/MS indicates high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry.

Discussion

For the most part, our understanding of spermatogenesis regulation in relationship to intratesticular steroids has come from mean values obtained from studies of groups of animals, not from comparisons of individual animals. It is clear from studies of men, however, that variation in intratesticular steroid levels from individual to individual can be considerable (Jarow et al, 2001). Additionally, whereas the administration of supraphysiological doses of testosterone suppresses spermatogenesis reversibly in some men (Liu et al, 2006), not all become azoospermic or even severely oligospermic (World Health Organization, 1996; Gu et al, 2003; Gui et al, 2004; Wang et al, 2006). Thus, it is clear that there are differences from man to man. We do not understand such differences in untreated men or why some men respond to exogenous testosterone administration while others respond far less robustly.

For many years, rats have served as a model for human spermatogenesis. However, little attention has been paid to individual differences in intratesticular steroids in untreated rats or to possible differences in the responses of individual rats administered dosages of testosterone or other hormones. We reasoned that such information, if available, could be of great value in learning more, at a basic/mechanistic level, about the relationship of intratesticular steroids to spermatogenesis regulation in individual rats and might provide information applicable to men. With this in mind, we undertook the present study to develop a method by which to measure T and DHT, in particular, and also E2 3α-diol, together in the small fluid volumes obtainable from rat testes. RIA typically is used to measure androgens and estrogens but can suffer from cross-reactivity with interfering substances, leading to potential problems with accuracy and specificity when steroids are at relatively low concentration (Hsing et al, 2007), as are most testosterone metabolites in intratesticular fluids (Turner et al, 1984; Zhao et al, 2004). T, DHT, E2, and 3α-diol have been measured without derivatization using HPLC-MS with positive electrospray ionization (Zhao et al, 2004). However, sensitivity depends on sample volumes available for analysis, which in the case of intratesticular fluids (eg, interstitial fluid) can be limiting. Oxime derivatization has been used for T and DHT with good specificity and sensitivity (Kalhorn et al, 2007; Roth et al, 2010a, b), but this approach does not allow simultaneous determination of E2 and 3α-diol. Likewise, dansyl chloride efficiently derivatizes E2 for low-level analysis but is not useful for analysis of compounds without phenolic hydroxyl groups (Falk et al, 2008).

The isotope dilution tandem mass spectrometry method described herein is both rapid and sensitive and allows the simultaneous measurement of picolinoyl derivatives of T, DHT, E2, and 3α-diol in small fluid volumes of intratesticular fluid obtained from individual adult rats. The use of stable deuterated internal standards for each analyte assures good accuracy and reproducibility. Instability in an analyte, because of methanol or other factors, during analysis would be expected to be corrected for by the internal standard; labeled and unlabeled analytes will degrade at the same rate and to the same extent. The use of tandem mass spectrometry assures the specificity of the method because signals are recorded only if molecules of known mass decompose in the mass spectrometer to produce predictable and specific fragment ions. For T and DHT, the sums of 2 specific transitions were monitored for quantification (Table 1). In such a case, the ratios of the signals for the 2 transitions must be the same in both analyte and internal standard for positive identification. For E2 and 3α-diol, only a single transition was available for quantification.

Steroids are often difficult to analyze directly by mass spectrometry, and derivatization has been used to enhance sensitivity (Higashi and Shimada, 2004; Nishio et al, 2007). Picolinoyl derivatization proceeds smoothly in quantitative yield as determined by mass spectrometry. For T and DHT, a picolinoyl group is added only at the C-17 aliphatic hydroxyl group, whereas for E2 and 3α-diol, picolinoyl groups are added at both the C-17 and C-3 hydroxyl groups (Figure 2). Even though we limited testicular fluid volumes to 10 μL, we were able to detect the 4 analytes reliably at levels of less than 1 ng/mL.

To diminish any decomposition of the analytes by enzymes in the fluid, samples were kept on ice at all times during initial workup and stored at −80°C, and freeze-thaw cycles were avoided. The accuracy for the analysis of the 4 analytes, spiked into stripped testicular fluid at 3 levels over greater than 2 orders of magnitude, was within the acceptable range of 80%–120%. Background levels were below the limit of determination for all 4 analytes in the pooled charcoal-stripped testicular fluid samples used for these studies. With the exception of interday reproducibility for 3α-diol, reproducibility was within the desired limit of 15% (Table 3). Accurate determination of the 3α-diol metabolite was more difficult because of its low concentration, stability issues, and interfering peaks in the transition monitored on the mass spectrometer. Reproducibility would be improved if a larger aliquot of testicular fluid were available, but better chromatographic separation might also be useful. Because higher levels for these analytes have been reported previously in human testicular fluid, it is expected that this method will be easily applicable to future studies involving human samples (Zhao et al, 2004).

To determine analytical variability within a group of animals, levels of T, DHT, E2, and 3α-diol were determined in the testicular fluid of 8 rats. As seen in Table 4, the T concentrations differed considerably from animal to animal (47–295 ng/mL). As in the human, this variability might be the result of how long after luteinizing hormone pulse samples were taken. The HPLC-MS/MS results for T in these samples were closely correlated with the results obtained by RIA (Figure 2), thus providing confidence in the reliability of the new HPLC-MS/MS method.

In summary, the Isotope Dilution-HPLC-MS/MS method presented herein will simultaneously measure all 4 steroids of interest, even if very small volumes. Compared with earlier methods, this method uses stable isotope–labeled compounds for all 4 internal standards that otherwise are structurally identical to their parent compounds. This allows accurate and precise quantitation correcting for ion suppression in the electrospray ion source and any loss during sample cleanup. The method is robust and rapid and should be able to handle the large numbers of samples obtained in clinical studies. This procedure for quantitating T, DHT, E2, and 3α-diol in testicular fluid should benefit research on the mechanisms underlying spermatogenesis, therefore broadening the understanding of both infertility and an inability to achieve azoospermia in individuals.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD/NIH through cooperative agreement U54 HD055740 as part of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research.

References

- Allan CM, Couse JF, Simanainen U, Spaliviero J, Jimenez M, Rodriguez K, Korach KS, Handelsman DJ. Estradiol induction of spermatogenesis is mediated via an estrogen receptor-{alpha} mechanism involving neuroendocrine activation of follicle-stimulating hormone secretion. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2800–2810. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awoniyi CA, Santulli R, Chandrashekar V, Schanbacher BD, Zirkin BR. Quantitative restoration of advanced spermatogenic cells in adult male rats made azoospermic by active immunization against luteinizing hormone or gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology. 1989a;125:1303–1309. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-3-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awoniyi CA, Santulli R, Sprando RL, Ewing LL, Zirkin BR. Restoration of advanced spermatogenic cells in the experimentally regressed rat testis: quantitative relationship to testosterone concentration within the testis. Endocrinology. 1989b;124:1217–1223. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-3-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awoniyi CA, Zirkin BR, Chandrashekar V, Schlaff WD. Exogenously administered testosterone maintains spermatogenesis quantitatively in adult rats actively immunized against gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology. 1992;130:3283–3288. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.6.1597140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Chandrashekar V, Zirkin BR. Can spermatogenesis be maintained quantitatively in intact adult rats with exogenously administered dihydrotestosterone? J Androl. 1994;15:132–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk RT, Xu X, Keefer L, Veenstra TD, Ziegler RG. A liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry method for the simultaneous measurement of 15 urinary estrogens and estrogen metabolites: assay reproducibility and interindividual variability. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3411–3418. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu YQ, Wang XH, Xu D, Peng L, Cheng LF, Huang MK, Huang ZJ, Zhang GY. A multicenter contraceptive efficacy study of injectable testosterone undecanoate in healthy Chinese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:562–568. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui YL, He CH, Amory JK, Bremner WJ, Zheng EX, Yang J, Yang PJ, Gao ES. Male hormonal contraception: suppression of spermatogenesis by injectable testosterone undecanoate alone or with levonorgestrel implants in Chinese men. J Androl. 2004;25:720–727. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb02846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi T, Shimada K. Derivatization of neutral steroids to enhance their detection characteristics in liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;378:875–882. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2252-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdcraft RW, Braun RE. Hormonal regulation of spermatogenesis. Int J Androl. 2004;27:335–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2004.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsing AW, Stanczyk FZ, Belanger A, Schroeder P, Chang L, Falk RT, Fears TR. Reproducibility of serum sex steroid assays in men by RIA and mass spectrometry. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1004–1008. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarow JP, Chen H, Rosner TW, Trentacoste S, Zirkin BR. Assessment of the androgen environment within the human testis: minimally invasive method to obtain intratesticular fluid. J Androl. 2001;22:640–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarow JP, Zirkin BR. The androgen microenvironment of the human testis and hormonal control of spermatogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1061:208–220. doi: 10.1196/annals.1336.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalhorn TF, Page ST, Howald WN, Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS. Analysis of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone from biological fluids as the oxime derivatives using high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:3200–3206. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PY, Swerdloff RS, Christenson PD, Handelsman DJ, Wang C. Rate, extent, and modifiers of spermatogenic recovery after hormonal male contraception: an integrated analysis. Lancet. 2006;367:1412–1420. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan RI, Wreford NG, O’Donnell L, de Kretser DM, Robertson DM. The endocrine regulation of spermatogenesis: independent roles for testosterone and FSH. J Endocrinol. 1996;148:1–9. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1480001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishio T, Higashi T, Funaishi A, Tanaka J, Shimada K. Development and application of electrospray-active derivatization reagents for hydroxysteroids. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2007;44:786–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page ST, Amory JK, Bremner WJ. Advances in male contraception. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:465–493. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts KP, Zirkin BR. Androgen regulation of spermatogenesis in the rat. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;637:90–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb27303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth MY, Lin K, Amory JK, Matsumoto AM, Anawalt BD, Snyder CN, Kalhorn TF, Bremner WJ, Page ST. Serum LH correlates highly with intratesticular steroid levels in normal men. J Androl. 2010a;31:138–145. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.109.008391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth MY, Page ST, Lin K, Anawalt BD, Matsumoto AM, Snyder CN, Marck BT, Bremner WJ, Amory JK. Dose-dependent increases in intratesticular testosterone by very low-dose human chorionic gonadotropin in normal men with experimental gonodotropin deficiency. Endocrinol Metab. 2010b;95:3806–3813. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruwanpura SM, McLachlan RI, Meachem SJ. Hormonal regulation of male germ cell development. J Endocrinol. 2010;205:117–131. doi: 10.1677/JOE-10-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanbacher BD, Ewing LL. Simultaneous determination of testosterone, 5alpha-androstan-17beta-ol-3-one, 5alpha-androstane-3al-pha,17beta-diol and 5alpha-androstane-3beta,17beta-diol in plasma of adult male rabbits by radioimmunoassay. Endocrinology. 1975;97:787–792. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-4-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner TT, Jones CE, Howards SS, Ewing LL, Zegeye B, Gunsalus GL. On the androgen microenvironment of maturing spermatozoa. Endocrinology. 1984;115:1925–1932. doi: 10.1210/endo-115-5-1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Wang XH, Nelson AL, Lee KK, Cui YG, Tong JS, Berman N, Lumbreras L, Leung A, Hull L, Desai S, Swerdloff RS. Levonorgestrel implants enhanced the suppression of spermatogenesis by testosterone implants: comparison between Chinese and non-Chinese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:460–470. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Contraceptive efficacy of testosterone-induced azoospermia and oligozoospermia in normal men. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:821–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita K, Okuyama M, Nakagawa R, Honma S, Satoh F, Morimoto R, Ito S, Takahashi M, Numazawa M. Development of sensitive derivatization method for aldosterone in liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry of corticosteroids. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1200:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita K, Okuyama M, Watanabe Y, Honma S, Kobayashi S, Numazawa M. Highly sensitive determination of estrone and estradiol in human serum by liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Steroids. 2007a;72:819–827. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita K, Takahashi M, Tsukamoto S, Numazawa M, Okuyama M, Honma S. Use of novel picolinoyl derivatization for simultaneous quantification of six corticosteroids by liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2007b;1173:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Baker SD, Yan X, Zhao Y, Wright WW, Zirkin BR, Jarow JP. Simultaneous determination of steroid composition of human testicular fluid using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Steroids. 2004;69:721–726. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirkin BR, Santulli R, Awoniyi CA, Ewing LL. Maintenance of advanced spermatogenic cells in the adult rat testis: quantitative relationship to testosterone concentration within the testis. Endocrinology. 1989;124:3043–3049. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-6-3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]