Abstract

Background

Preschool-onset depression, a developmentally adapted form of depression arising between the ages of 3–6, has demonstrated numerous features of validity including characteristic alterations in stress reactivity and brain function. Notably, this validated syndrome with multiple clinical markers is characterized by sub-threshold DSM Major Depressive Disorder criteria, raising questions about its clinical significance. To clarify the utility and public health significance of the preschool-onset depression construct, diagnostic outcomes of this group at school age and adolescence were investigated.

Methods

We investigated the likelihood of meeting full DSM Major Depressive Disorder criteria in later childhood (i.e., ≥ age 6) as a function of preschool depression, other preschool Axis I disorders, maternal depression, parenting non-support and traumatic life events in a longitudinal prospective study of preschool children.

Results

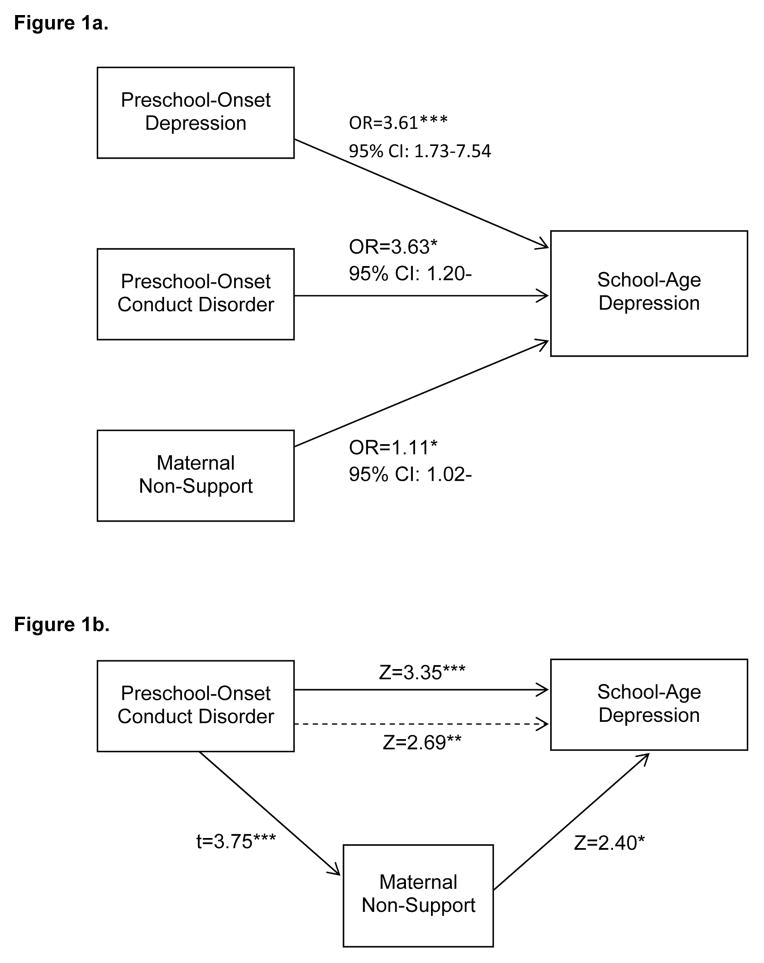

Preschool-onset depression emerged as a robust predictor of DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder in later childhood even after accounting for the effect of maternal depression and other risk factors. Preschool-onset conduct disorder also predicted DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder in later childhood, but this association was partially mediated by maternal non-support, reducing the effect of preschool conduct disorder in predicting DSM depression by 21%.

Discussion

Study findings provide evidence that this preschool depressive syndrome is a robust risk factor for meeting full DSM criteria for Major Depressive Disorder in later childhood over and above other established risk factors. Preschool conduct disorder also predicted Major Depressive Disorder but was mediated by maternal non-support. Findings suggest that attention to preschool depression and conduct disorder in addition to maternal depression and exposure to trauma should now become an important factor for identification of young children at highest risk for later MDD who should be targeted for early interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Several independent studies have provided data suggesting that a clinically significant form of depression can arise as early as age 3 (1–4). The identification of the earliest developmental manifestations of depression is critical to target interventions prior to the time that a chronic and relapsing illness trajectory becomes established. Preschool-onset depression is a form of depression observed in children between the ages of 3 and 6 and characterized by age adjusted manifestations of the core DSM-5 symptoms of depression (e.g. neuro-vegetative signs, anhedonia and guilt) known in older children and adults. Preschool depression has been shown to have content and discriminant validity, homotypic continuity over 18–24 months, higher rates of familial affective disorders compared to healthy controls, and biological correlates (2, 5, 6). These features are markers of validation for psychiatric disorders following criteria originally outlined by Robins and Guze (7). The validity of preschool depression has been established across multiple independent study samples providing support for the public health importance of this construct (see ST1). Importantly, more recently, similar alterations in brain function and structure known in depressed adults have also been detected at school-age in children who experienced an episode of preschool-onset depression as well as in depressed preschoolers themselves (8–11). Based on these findings, the need for early identification and intervention is further enhanced by the potential to interrupt the disease trajectory during a period of greater neural plasticity.

Based on estimates of prevalence and reports of referral in clinical settings, depression in preschool children appears to be a clinically under-recognized disorder (4, 12, 13). As preschool depression is not inherently disruptive, and preschoolers are less likely to spontaneously report their internalized distress than older children, these early onset depressive symptoms often go undetected by caregivers. However, findings that depressed preschoolers were significantly impaired across contexts and activities when rated by teachers and parents support its clinical significance (2). Common but non-specific clinical symptoms of preschool depression are sadness and irritability. More specific markers that are useful to distinguish preschool depression from other preschool disorders are increased expression of and preoccupation with guilt, changes in sleep, appetite and activity level, as well as decreased pleasure in activities and play, the latter not normative during the preschool period when joyful play exploration is a central developmental theme (2). In keeping with this, the lack of joyfulness may be more apparent in the preschool child than overt sadness. Persistent preoccupation with negative play themes may also be a tangible clinical sign. As depressed preschoolers rarely appear persistently withdrawn, sad or vegetative and do not appear to display sustained depressive symptoms for a two-week period, but instead show periods of age appropriate brightening, it is important to look for circumscribed yet recurrent manifestations of these symptoms over time.

Notably, this syndrome with markers of validity and features suggestive of clinical significance is characterized by sub-threshold DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder criteria (14). As previously described, when identifying preschool depression the two-week duration criterion is not strictly enforced and preschoolers who meet at least 4 (versus the required 5) symptoms for a DSM Major Depressive Disorder episode were included in this clinical group based on markers of validation (6, 14, 15). The fact that depressed preschoolers failed to meet full DSM criteria for Major Depressive Disorder has raised questions about its clinical and public health significance with some suggesting that preschool-onset depression represents a risk state or a “minor” depression. Alternatively, others have argued that there may be developmental differences in the temporal manifestations of affective disorders in early childhood and that adjustments to clinical criteria for some Axis I disorders may be indicated. One example of this is the criteria for early childhood Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in DSM-5, allowing for the use of developmentally modified symptom manifestations as well as requiring a decreased number of symptoms to qualify for the disorder (16). Whether this is scientifically justified in depression remains an issue of debate leaving the precise public health and clinical significance of preschool depression unresolved.

In an attempt to further clarify the public health significance of preschool depression, we investigated the risk of meeting full DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder criteria at school-age and early adolescence in a longitudinal sample of depressed preschool children as well as healthy and psychiatric controls. Longitudinal outcomes of childhood disorders have been an important element of establishing diagnostic validity, and this criterion was prioritized in decision making for modifications to childhood disorders in DSM-5. Notably, both heterotypic and homotypic longitudinal outcomes of school age and adolescent depression have been reported in several key study samples (17, 18). Therefore, whether preschool depression was also a risk factor for other Axis I disorders at school-age and early adolescence was also explored.

Also of interest was whether psychosocial predictors could be identified to inform which preschoolers were at greater risk for later diagnosis of full DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder. We hypothesized that specific environmental/familial conditions, including maternal depression, parenting non-support, and traumatic or stressful life events, would be predictors of later full DSM-5 criteria. Of additional interest was what other Axis I preschool-onset disorders increased the risk for DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder at school-age and early adolescence and particularly whether an anxiety disorder during the preschool period would be a predictor of later DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder, as has been demonstrated by studies in older children (19).

Based on the notion that preschool-onset depression is an early manifestation of the well-validated later childhood disorder, we hypothesized that preschool depression would exceed other Axis I preschool disorders and salient risk factors as a robust risk factor for meeting full DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder criteria at school-age and early adolescence. Given the clear importance of income to needs and negative parenting as risk factors for a variety of poor developmental outcomes in numerous studies including this one, and maternal Major Depressive Disorder as a risk factor for childhood depression, these variables were of particular interest (20–22). If clear predictors of the later full DSM-5 disorder could be identified, they could inform which preschoolers should be targeted for early intervention.

METHODS

Study Population

Preschoolers between the ages of 3.0–5.11 years were recruited from primary care and daycare sites in the St. Louis community using the Preschool Feelings Checklist (PFC), a validated screening measure for identifying children at high risk for preschool-onset depression (23, 24). Child participants with symptoms of depression were oversampled, and those with symptoms of other psychiatric disorders and healthy controls were also included as comparison groups. Further details of study recruitment methods and subject flow have been previously described in Luby et al., 2009 (25). The full details of recruitment and subject flow across study waves are available in Supplemental Figure 1. Study subjects and their primary caregivers participated in up to 6 comprehensive annual (and up to 4 semi-annual) assessments conducted at the Early Emotional Development Program (EEDP) at the Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM). Supplemental Table 2 details the mean number of preschool and school-age assessments completed in the sample. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained from parents, and assent was obtained from children. All study procedures were approved by the WUSM IRB.

Measures

Child Psychopathology and Stressful and Traumatic Life Events

Assessments included a comprehensive age-appropriate diagnostic interview that assessed for the presence of DSM Axis I psychiatric disorders as well as stressful and traumatic life events at each study wave. When children were aged 3.0–7.11 years, the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) was administered to caregivers (26). When children were 8.0 years or older, both child and caregiver report of psychiatric symptoms were assessed using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA; the interview from which the PAPA was adapted) (27, 28). The PAPA and CAPA have established test-retest reliability and include all relevant DSM criteria and their age appropriate manifestations (27, 29). Both interviews also have established reliability for the assessment of stressful/traumatic life events (30, 31). Parent and child report on the CAPA were combined by taking the most severe rating, as is the standard in child depression research. Raters trained to reliability and blind to the subject’s diagnostic status from prior waves administered the PAPA/CAPA at each assessment point. Blind ratings were achieved based on the large study sample assessed over a 10-year period and the ability to have different interviewers rate subjects at each wave. In addition, the diagnosis is derived using a computer based DSM algorithm using all endorsed symptoms making diagnostic determinations more objective. High test re-test reliability for the Major Depressive Disorder module on the PAPA (for diagnosis kappa=0.62 and symptom endorsement intra-class correlations=0.88) and high inter-rater reliability (kappa=0.79 ICC=0.97) has been established in our lab (9, 32). All interviews were audiotaped and methods to maintain reliability and prevent drift, which include ongoing calibration of interviews by master raters for 20% of each interviewer’s cases, were done in consultation with an experienced clinician (JLL) at each study wave.

There are 18 stressful (e.g., change in daycare/school) and 21 traumatic (e.g., death of a loved one) life events assessed in the PAPA/CAPA. The frequencies of occurrences of all types of stressful and traumatic life events were summed to create an overall stressful life event frequency and an overall traumatic life event frequency.

Income to Needs

Income to needs was computed as the total family income at baseline divided by the federal poverty level based on family size in the year nearest that of data collection (33).

Pubertal Status

Pubertal status was rated at each study wave for subjects aged 10 and over using the Pubertal Status Questionnaire, a validated self-report measure of pubertal development (34).

Maternal history of depression

The Family Interview for Genetic Studies (FIGS)(35) was used to obtain maternal and family history of depression and other affective disorders in first- and second-degree relatives. At each wave of data collection, primary caregivers (93% mothers) were interviewed about family history of psychiatric disorders, and the screening checklist for Major Depressive Disorder was given when screening items were endorsed. Therefore, maternal history of depression was obtained based on mothers’ self-report using the FIGS Major Depressive Disorder screener and/or based on history of clinician diagnosis in 93% of cases (7% based on other caregiver report). The FIGS is a fully structured measure for which the senior investigator trained interviewers on administration to reliability (35). Questions about the diagnostic status of a family member were reviewed by a senior psychiatrist (JLL) blind to the preschool subject’s diagnostic status. FIGS data were obtained for all subjects and updated at each annual study wave.

Maternal Non-Support

At the first annual follow-up wave, children and parents were observed interacting during a mildly stressful task, in which the child must wait for 8 minutes before opening an attractive gift sitting within arm’s reach. The interaction was coded for parents’ use of non-supportive (e.g., threats about negative consequences) caregiving strategies. High inter-rater reliability (>0.83) of coders has been established in the study sample. This task is well-validated and is used for assessing parenting strategies and has good psychometric properties (36–38).

Data Analysis

For the purpose of the analyses that follow, dichotomous variables were used for the presence/absence of preschool onset diagnoses. This approach was used to account for the effect of specific disorders independent of levels of co-morbidity (common in childhood psychopathology). Specifically, children who met the previously validated criteria for depression (described above) prior to the age of 6.0 years were considered to have preschool-onset depression. Similarly, preschoolers who met criteria for Axis I disorders prior to the age of 6.0 were placed in the following preschool onset groups: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, and Conduct Disorder. Children who had Separation Anxiety, Generalized Anxiety, or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder prior to age 6.0 were categorized in a broader preschool-onset anxiety group. Children’s school age axis I DSM-5 diagnostic outcomes at 6–13 years of age were defined in the same fashion (see Table 1 for details of co-morbidity at preschool and school age). No exclusions were applied, therefore any child who met criteria for a given diagnosis was included in that group regardless of co-morbidity. Importantly, subjects with depression at ≥ age 6 at school age were required to meet full DSM-5 criteria for a Major Depressive Episode, i.e., five or more symptoms at a clinically impairing severity level lasting for at least 2 weeks. School-age diagnoses were created in a parallel fashion for the remaining preschool disorders (e.g., school-age oppositional defiant disorder) at ages 6–13 years.

Table 1.

Comorbid Diagnoses in Subjects with Preschool-Onset Depression (N=74) and in Subjects with School-Age Depression (N=79)

| Preschool-Onset Depression (N=74)

|

||

|---|---|---|

| % | N | |

| Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder | 24.3 | 18 |

| Preschool-Onset Anxiety Disorder | 45.9 | 34 |

| Preschool-Onset ADHD | 31.1 | 23 |

| Preschool-Onset Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 50.0 | 37 |

| School-Age Depression (N=79)

|

||

|---|---|---|

| % | N | |

| School-Age Conduct Disorder | 32.9 | 26 |

| School-Age Anxiety Disorder | 58.2 | 46 |

| School-Age ADHD | 51.9 | 41 |

| School-Age Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 45.6 | 36 |

For the analyses that follow, continuous variables were centered by subtracting the mean, and dichotomous variables were centered by assigning values of -1 and 1 to the two outcomes. Potential Covariates. Independent logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine whether children’s gender and or age at baseline were significantly associated with the likelihood of being diagnosed with school-age depression. Variables significantly associated with school-age depression status were then included as covariates in the final analysis.

Preschool-Onset Psychiatric Disorders Predicting School-Age Depression Diagnosis

Using logistic regression analyses, we calculated the odds ratios for diagnosis of school-age depression based on the presence/absence of five possible preschool-onset psychiatric disorders. School-age depression (y/n) was the dependent variable and preschool-onset depression, conduct, anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactivity, and oppositional defiant disorders were entered simultaneously as dichotomous predictor variables. Although school-age depression was the outcome diagnosis of most interest, four additional logistic regression models were conducted for comparison purposes using school-age conduct, anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactivity, and oppositional defiant disorders as the outcome variables.

Familial/Environmental Predictors of School-Age Depression

Five separate logistic regression analyses were conducted to test for main effects of environmental/familial risk factors on school-age depression as well as to test for interaction effects between environmental/familial variables and preschool-onset diagnoses in relation to school-age. Interactions between preschool diagnosis and environmental/familial variables were explored to test for mediation or moderation effects which are known in risk trajectories. For each regression the independent variables were the main effect of a single environmental/familial variable (income-to-needs, maternal history of Major Depressive Disorder, traumatic life events, stressful life events or observed non-supportive caregiving behaviors), main effect of one or more preschool-onset psychiatric disorders that significantly predicted school-age depression in the preceding analyses, and the interaction term(s) between environmental/familial variable X preschool-onset disorder. School-age depression was the outcome variable for each analysis.

Final Cumulative Model Predicting School-Age Depression

Based on findings from the previous analyses, we tested all significant predictors of school-age depression simultaneously using hierarchical logistic regression.

Non-Supportive Caregiving as a Mediator of the Relationship between Preschool-Onset Diagnoses and School-Age Depression

Maternal non-support has been found to mediate the effects of preschool-onset psychiatric disorders on numerous behavioral and biological outcomes in the current sample as well as in other independent samples (20, 21). Thus, we conducted formal tests for non-support as a possible mediator of the significant association between preschool-onset psychiatric disorders and school-age depression (i.e., outcome variable of interest). In keeping with a traditional approach to mediation and its definition, we proceeded with tests for mediation only if the preschool-onset disorder significantly predicted school-age depression and the same preschool-onset disorder significantly predicted nonsupport. When a preschool-onset diagnosis predicted school-age depression but did not significantly predict caregiving nonsupport (the mediator), mediation was not tested, as this would violate a fundamental tenant of mediation, making formal mediation analysis unreliable. Mediation analyses were conducted using the process macro for SAS (39).

Analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and SPSS version 21 (SPSS IBM, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

There were N=246 subjects included in the analyses, and characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 2. This subsample of N=246 out of the N=306 subjects enrolled at baseline was included in the analyses, because they had complete data on the key variables on interest. The N=246 subjects included in the analyses did not differ demographically from the N=60 subjects not included in the analysis, except that higher levels of parental education had been obtained in subjects included in the analysis compared to those not included (χ2=8.10, p=0.044). Of subjects with school-age depression, 82.3% were pre-pubertal at the time of onset. 43.5% of subjects without school-age depression were pre-pubertal at the time of the last completed assessment. The mean duration of participants’ follow up period was 6.44 years (SD 1.04 years).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Sample (N=246)

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline age | 4.47 | 0.80 |

| Age at school-age depression onset (N=79) | 9.34 | 1.57 |

| Age at last assessment | 10.91 | 1.22 |

| Baseline income to needs ratio | 2.24 | 1.20 |

| Traumatic life events frequency | 7.50 | 13.21 |

| % | N | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 51.6 | 127 |

| Female | 48.4 | 119 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 56.5 | 139 |

| African-American | 31.3 | 77 |

| Other | 12.2 | 30 |

| Baseline family income | ||

| <$20,000 | 22.4 | 55 |

| $20,001-$40,000 | 17.1 | 42 |

| $40,001-$60,000 | 19.5 | 48 |

| ≥$60,000 | 41.1 | 101 |

| Baseline parental education* | ||

| High school diploma | 15.6 | 38 |

| Some college | 37.9 | 92 |

| 4-year college degree | 21.4 | 52 |

| Graduate education | 25.1 | 61 |

| Maternal MDD | 39.0 | 96 |

| Preschool-onset diagnoses** | ||

| Depression | 30.1 | 74 |

| Conduct Disorder | 15.9 | 39 |

| Anxiety Disorder | 30.1 | 74 |

| ADHD | 17.1 | 42 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 28.0 | 69 |

| School-age diagnoses** | ||

| Depression | 32.1 | 79 |

| Conduct Disorder | 16.3 | 40 |

| Anxiety Disorder | 31.3 | 77 |

| ADHD | 25.6 | 63 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 24.0 | 59 |

Parental education was taken from the parent who completed the assessment, the biological mother in 93% of cases

Study subjects may be counted in more than 1 diagnostic group due to co-morbidity.

Potential Covariates

Results indicated that children’s baseline age, but not gender (p=0.278), predicted the likelihood of being diagnosed with school-age depression (OR=1.88, 95% CI: 1.31, 2.70, p<0.001). That is, the older children were at baseline the more likely they were to be diagnosed with school-age depression. Thus, final analyses included children’s age but not gender as a covariate.

Preschool Onset Psychiatric Disorders as Predictor(s) of School-Age Depression As hypothesized, children previously diagnosed with preschool-onset depression were more than 2.5 times as likely as children without preschool depression to be diagnosed with school-age depression (see Table 3). The occurrence of school-age depression in the N=74 children diagnosed with preschool-onset depression was 51.4%, while the rate of school-age depression in the N=172 subjects without preschool-onset depression was 23.8%. Preschool-onset conduct disorder was the only other significant predictor of school-age depression (p=0.003). No other Axis I preschool diagnosis significantly increased the likelihood of school-age depression.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios for School-Age and Early Adolescent Disorders from Preschool Disorders (N=246)

| School-Age Depression

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | χ2 | p | |

| Preschool-Onset Depression | 2.70 | (1.43, 5.08) | 9.45 | 0.0021 |

| Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder | 3.38 | (1.50, 7.62) | 8.63 | 0.0033 |

| Preschool-Onset Anxiety Disorder | 1.53 | (0.81, 2.88) | 1.69 | 0.1934 |

| Preschool-Onset ADHD | 1.30 | (0.56, 3.01) | 0.38 | 0.5382 |

| Preschool-Onset Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 1.02 | (0.49, 2.13) | 0.00 | 0.9570 |

| School-Age Conduct Disorder

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | χ2 | p | |

| Preschool-Onset Depression | 1.79 | (0.81, 3.95) | 2.07 | 0.1499 |

| Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder | 4.56 | (1.92, 10.86) | 11.74 | 0.0006 |

| Preschool-Onset Anxiety Disorder | 1.50 | (0.67, 3.35) | 0.98 | 0.3217 |

| Preschool-Onset ADHD | 1.32 | (0.50, 3.50) | 0.32 | 0.5729 |

| Preschool-Onset Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 1.75 | (0.73, 4.23) | 1.56 | 0.2116 |

| School-Age Anxiety Disorder

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | χ2 | p | |

| Preschool-Onset Depression | 3.48 | (1.86, 6.51) | 15.26 | <0.0001 |

| Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder | 1.01 | (0.43, 2.35) | 0.00 | 0.9883 |

| Preschool-Onset Anxiety Disorder | 1.91 | (1.02, 3.61) | 4.03 | 0.0448 |

| Preschool-Onset ADHD | 1.23 | (0.52, 2.88) | 0.22 | 0.6419 |

| Preschool-Onset Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 1.72 | (0.83, 3.54) | 2.12 | 0.1449 |

| School-Age ADHD

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | χ2 | p | |

| Preschool-Onset Depression | 3.69 | (1.84, 7.40) | 13.53 | 0.0002 |

| Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder | 1.93 | (0.80, 4.63) | 2.15 | 0.1430 |

| Preschool-Onset Anxiety Disorder | 1.08 | (0.52, 2.28) | 0.05 | 0.8312 |

| Preschool-Onset ADHD | 3.00 | (1.26, 7.14) | 6.15 | 0.0131 |

| Preschool-Onset Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 2.88 | (1.36, 6.11) | 7.57 | 0.0059 |

| School-Age Oppositional Defiant Disorder

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | χ2 | p | |

| Preschool-Onset Depression | 1.94 | (0.95, 3.96) | 3.30 | 0.0694 |

| Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder | 2.34 | (1.00, 5.45) | 3.86 | 0.0493 |

| Preschool-Onset Anxiety Disorder | 1.02 | (0.48, 2.14) | 0.00 | 0.9693 |

| Preschool-Onset ADHD | 1.60 | (0.67, 3.85) | 1.11 | 0.2920 |

| Preschool-Onset Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 4.62 | (2.18, 9.76) | 16.05 | <0.0001 |

Preschool-Onset Depression as a Predictor of Other School-Age Disorders

Table 3 outlines the relationships between all preschool disorders and school age disorders. Notably, children with preschool-onset depression (in addition to those with preschool-onset ADHD, and/or preschool-onset oppositional defiant disorder) were on average 3 times as likely as children without these preschool diagnoses to be diagnosed with school-age depression. Results also indicated that children previously diagnosed with preschool-onset depression and/or preschool-onset anxiety disorder were significantly (p<0.05) more likely than children without these diagnoses to be diagnosed with school-age anxiety disorder.

As the current study aim was to identify risk factors for DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder in later childhood, the remaining analyses include only the 2 preschool-onset disorders found to significantly predict school-age depression (i.e., preschool-onset depression and preschool-onset conduct disorder).

Familial/Environmental Predictors of School-Age Depression

Income-to-Needs Ratio

Children from families with lower income-to-need ratios (i.e., measured at baseline when subjects were preschool age) were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with school-age depression (OR=1.35, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.70, p=0.012). The interaction effects of income-to-needs x preschool-onset depression and income-to-needs x preschool-onset conduct disorder were non-significant (p’s > 0.2), in relation to school-age depression diagnosis.

Maternal History of Major Depressive Disorder

Children with school-age depression were almost twice as likely to have a mother with depression compared to those without school-age depression (OR=1.88, 95% CI: 1.09, 3.24, p=0.023). The interaction effects of maternal depression x preschool-onset depression and maternal depression x preschool-onset conduct disorder were non-significant (p>0.2) in relation to school-age depression diagnosis.

Observed Non-Supportive Caregiving Strategies

Children with primary caregivers who were observed using non-supportive caregiving strategies more frequently during the Parent-Child Interaction task were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with school-age depression (OR=1.08, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.15, p=0.020). The interaction effects of non-supportive parenting x preschool-onset depression and non-supportive parenting x preschool-onset conduct disorder were not significant (p’s>0.4) in relation to school-age depression diagnosis.

Stressful and Traumatic Life Events

Results indicated that the frequency of stressful life events experienced by children did not predict school-age depression (OR=1.00, 95% CI: 0.98, 1.02, p=0.996). In contrast, children’s experiences of traumatic life events approached statistical significance as a predictor of school-age depression (OR=1.02, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.05, p=0.090). The interaction effects of trauma x preschool-onset depression and trauma x preschool-onset conduct disorder were non-significant (p’s>0.2) in relation to school-age depression diagnosis. Trauma was also included in the final model despite it only approaching statistical significance given its importance in the extant literature and in our own sample as a predictor of school-age depression.

Examining Diagnostic and Environmental/Familial Predictors of School-Age Depression Simultaneously

As seen in Table 4, step 1 of the analyses included children’s age at baseline and the significant environmental/familial variables. At step 2, the main effect of preschool-onset depression, preschool-onset conduct disorder, and the preschool-onset depression x preschool-onset conduct disorder interaction term were entered into the regression equation. Results indicated that when examined simultaneously in step 1 of the model, caregivers’ observed use of non-supportive caregiving strategies and children’s age at baseline were the only significant environmental/familial predictors of school-age depression. That is, preschoolers with caregivers who used non-supportive parenting strategies more frequently were significantly (p=0.019) more likely to be diagnosed with school-age depression. When preschool-onset depression and preschool-onset conduct disorder were included at step 2, children’s baseline age, non-supportive parenting, preschool-onset conduct disorder, and preschool depression were all significant predictors of school-age depression.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Logistic Regression Model of School-Age Depression in All Subjects (N=246)

| Est. | SE | OR | 95% CI | χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Baseline age | 0.71 | 0.20 | 2.03 | (1.39, 2.98) | 13.15 | <0.001 |

| Family income to needs ratio | -0.23 | 0.13 | 0.80 | (0.62, 1.02) | 3.37 | 0.066 |

| Traumatic life events frequency a | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.02 | (1.00, 1.04) | 2.98 | 0.085 |

| Maternal Depression a | 0.50 | 0.30 | 1.64 | (0.92, 2.94) | 2.81 | 0.094 |

| Maternal non-support | 0.09 | 0.04 | 1.09 | (1.02, 1.18) | 5.55 | 0.019 |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Baseline age | 0.81 | 0.21 | 2.24 | (1.48, 3.38) | 14.73 | <0.001 |

| Family income to needs ratio | -0.16 | 0.13 | 0.85 | (0.66, 1.10) | 1.49 | 0.223 |

| Traumatic life events frequency a | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.01 | (0.99, 1.03) | 0.59 | 0.444 |

| Maternal Depression a | 0.36 | 0.32 | 1.43 | (0.77, 2.65) | 1.28 | 0.258 |

| Maternal non-support | 0.10 | 0.04 | 1.11 | (1.02, 1.21) | 5.74 | 0.017 |

| Preschool-Onset Depression | 1.28 | 0.38 | 3.61 | (1.73, 7.54) | 11.72 | 0.001 |

| Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder | 1.29 | 0.56 | 3.63 | (1.20, 10.95) | 5.23 | 0.022 |

| Preschool-Onset Depression x | -0.28 | 0.82 | 0.75 | (0.15, 3.75) | 0.12 | 0.728 |

| Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder | ||||||

For subjects with school-age depression, time frame is prior to onset of the disorder. For subjects without school-age depression, time frame is through final assessment.

Associations between Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder and School-Age Depression: Non-Supportive Parenting as a Mediator

Before conducting formal tests of maternal non-support as a mediator of the relation between preschool depression and/or preschool-onset conduct disorder and school-age depression, mean scores of non-support in four diagnostic groups (preschool depression and conduct disorder, preschool depression only, preschool conduct disorder only, and neither preschool depression or conduct disorder) were calculated. As shown in Table 5, in a general linear model with pair-wise group contrasts, maternal non-support was significantly greater in the preschool conduct disorder only group compared to the other three diagnostic groups (preschool depression and conduct disorder: F=11.73, p<0.001; preschool depression only: F=35.21, p<0.001; neither preschool depression or conduct disorder: F=24.41, p<0.001). Based on this, a formal test of mediation was conducted for the relationship between preschool conduct disorder and school-age depression (mediation was not tested for preschool depression since it was not significantly associated with non-support). The effect of preschool conduct disorder on school-age depression was partially mediated through maternal non-support (95% bootstrap CI: 0.019, 0.364). The effect of preschool conduct disorder on school-age depression was reduced by 21% when non-support was accounted for in the model.

DISCUSSION

Study findings demonstrate that preschool depression was a significant and robust predictor for meeting full DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder criteria in later childhood and early adolescence (i.e., ages 6 to 13). The predictive power of preschool depression for school-age depression remained strong and undiminished even when other key environmental and familial risk factors were included in the model. Preschool conduct disorder also remained significant, although its effect was diminished when maternal non-support was accounted for. This finding extends the available data by demonstrating that preschool depression not only shows homotypic continuity up to 2 years later but also converts to meet all formal DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder criteria during school-age and early adolescence (mean 6 years later). This finding of DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder as a longitudinal outcome of preschool-onset depression further supports the significance and robustness of the preschool depression construct.

Preschool depression was also a risk factor for later anxiety disorders (OR 3.48) and ADHD (OR 3.69) at school age, underscoring its heterotypic in addition to homotypic outcomes. Heterotypic, and well as homotypic, outcomes of prepubertal depression have been reported in several other longitudinal samples (17, 18). Weissman et al., 1999 have suggested further that those children with prepubertal depression and a family history of depression have the highest risk of a recurrence of depression during adulthood. Consistent with the extant literature on risk for depression in older children, preschool conduct disorder also emerged as a significant predictor of later full DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder. The finding that disruptive disorders are risk factors for childhood depression has been established in several prior studies of school-aged children (40). In a prior analysis of this study sample, disruptive disorders during the preschool period also emerged as a risk factor for later depression at the 2 year follow-up point (6). However, notably the predictive power of this relationship was diminished in the current study when the effects of maternal non-support were considered in the analysis. Formal testing for mediation showed that the effect of preschool conduct disorder on later school-age depression was partially mediated by maternal non-support, suggesting that non-support in the context of conduct disorder is an important factor in the mechanism by which the risk for later depression is transmitted. Further, targeted study of this risk trajectory is now indicated.

Notably, in this investigation of multiple risk factors for school-age depression using a hierarchical logistic regression, and after accounting for other known significant risk factors, preschool depression remained a highly significant predictor of meeting later full Major Depressive Disorder criteria. These findings suggested that the preschool diagnosis was a stronger predictor of later full DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder than maternal depression or traumatic life events. This finding contradicts common clinical belief and practice where these latter risk factors are viewed as highly significant risk markers, while young child symptom characteristics and preschool depression diagnosis are generally considered more secondarily (or not at all) in the domain of risk for depression. While these findings do not address the question of whether preschool depression represents minor depression or a risk state during the preschool period, they should dispel any doubt that it is a group that is clearly and uniquely at high risk for later depression and therefore should be targeted for early intervention.

This study also provided data to inform the relationship between preschool anxiety disorders and later childhood depression. In contrast to findings in adults and older children, preschool anxiety disorders did not emerge as a precursor of school-age and early adolescent depression. However, preschool depression emerged as a risk factor for later school-age anxiety disorders (as well as later school-age ADHD). The inconsistency of this finding relative to this established risk trajectory in older children and adults could be related to a number of developmental factors. One possibility is the more transient nature of early onset anxiety disorders, which in some cases may represent a developmental extreme (e.g. Separation Anxiety Disorder) rather than a clinical disorder.

The most salient limitations of the study include the relatively small sample of children with preschool depression and the fact that the majority of subjects have not yet been followed through puberty. Thus, future studies that carefully track the sample through the pubertal period are needed to fully inform which preschoolers displaying depressive symptoms will not be at risk for a recurrent course. Nevertheless, the finding that preschool depression is a robust predictor of future DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder makes a strong case for using validated age-adjusted criteria to identify this early depressive phenotype prior to school age. Study findings are also of importance when considering that early intervention for depression in the preschool period, a point of high relative neuroplasticity, may provide a window of therapeutic opportunity to alter the chronic and relapsing course known in depressive disorders.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Preschool-Onset Depression, Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder, and Maternal Non-Support Significantly Associated with School-Age Depression in Logistic Regression Model

Figure 1b. Maternal Non-Support as a Partial Mediator of the Relationship between Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder and School-Age Depression

Covariates in the models included baseline age, family income to needs ratio, traumatic life events frequency, maternal depression, and the interaction between preschool-onset depression and preschool-onset conduct disorder; Solid arrows indicate total effect of X on Y; Dotted arrow indicates direct effect of X on Y; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Table 5.

Maternal Non-Support by Preschool-Onset Depression and Conduct Disorder Diagnoses

| Maternal Non-Support | Group Comparisons (p*) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Preschool-Onset Depression & Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder | Preschool-Onset Depression Only | Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder Only | Neither Preschool-Onset Depression or Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder | |

| Preschool-Onset Depression & Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder | 4.06 | 4.77 | ||||

| Preschool-Onset Depression Only | 2.39 | 2.14 | 0.124 | |||

| Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder Only | 8.43 | 8.34 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Neither Preschool-Onset Depression or Preschool-Onset Conduct Disorder | 3.85 | 3.46 | 0.839 | 0.020 | <0.001 | |

Bonferroni-corrected significant p=0.008

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH Grants 2R01 MH064769-06A1 (J.L.) and PA-07-070 NIMH R01 (J.L.). Dr. Belden’s work on this manuscript was supported by NIMH K01 MH090515-01 and Dr. Gaffrey’s work by NIMH K23 MH098176. The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Drs. Luby, Gaffrey and Belden, Ms. Tillman and Ms. April report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

We wish to acknowledge our child participants and their parents whose participation and cooperation made this research possible.

References

- 1.Luby JL, Heffelfinger A, Mrakotsky C, Brown K, Hessler M, Wallis J, Spitznagel E. The clinical picture of depression in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:340–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luby JL, Belden AC, Pautsch J, Si X, Spitznagel E. The clinical significance of preschool depression: Impairment in functioning and clinical markers of the disorder. J Affect Disord. 2009;112:111–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bufferd SJ, Dougherty LR, Carlson GA, Rose S, Klein DN. Psychiatric disorders in preschoolers: Continuity from ages 3 to 6. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1157–64. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12020268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egger H, Angold A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:313–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luby JL, Heffelfinger A, Mrakotsky C, Brown K, Hessler M, Spitznagel E. Alterations in stress cortisol reactivity in depressed preschoolers relative to psychiatric and no-disorder comparison groups. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1248–55. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luby JL, Si X, Belden AC, Tandon M, Spitznagel E. Preschool depression: Homotypic continuity and course over 24 months. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:897–905. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robins E, Guze SB. Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: its application to schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1970;126:983–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.126.7.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barch DM, Gaffrey MS, Botteron KN, Belden AC, Luby JL. Functional brain activation to emotionally valenced faces in school-aged children with a history of preschool-onset major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:1035–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaffrey MS, Barch DM, Singer J, Shenoy R, Luby JL. Disrupted amygdala reactivity in depressed 4- to 6-year-old children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:737–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaffrey MS, Luby JL, Botteron K, Repovs G, Barch DM. Default mode network connectivity in children with a history of preschool onset depression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:964–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaffrey MS, Luby JL, Repovs G, Belden AC, Botteron KN, Luking KR, Barch DM. Subgenual cingulate connectivity in children with a history of preschool-depression. Neuroreport. 2010;21:1182–8. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32834127eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavigne JV, LeBailly SA, Hopkins J, Gouze KR, Binns HJ. The prevalence of ADHD, ODD, depression, and anxiety in a community sample of 4-year-olds. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38:315–28. doi: 10.1080/15374410902851382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luby JL, Morgan K. Characteristics of an infant/preschool psychiatric clinic sample: Implications for clinical assessment and nosology. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1997;18:209–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luby JL, Mrakotsky C, Heffelfinger A, Brown K, Spitznagel E. Characteristics of depressed preschoolers with and without anhedonia: Evidence for a melancholic depressive subtype in young children. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1998–2004. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaffrey MS, Belden AC, Luby JL. The 2-week duration criterion and severity and course of early childhood depression: implications for nosology. J Affect Disord. 2011;133:537–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. 5. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. DSM-5 Task Force. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and Development of Psychiatric Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–44. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weissman MM, Wolk S, Wickramaratne P, Goldstein RB, Adams P, Greenwald S, Ryan ND, Dahl RE, Steinberg D. Children with prepubertal-onset major depressive disorder and anxiety grown up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:794–801. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole DA, Peeke LG, Martin JM, Truglio R, Seroczynski AD. A longitudinal look at the relation between depression and anxiety in children and adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:451–60. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luby JL, Barch DM, Belden A, Gaffrey MS, Tillman R, Babb C, Nishino T, Suzuki H, Botteron KN. Maternal support in early childhood predicts larger hippocampal volumes at school age. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2854–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118003109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luby J, Belden A, Botteron K, Marrus N, Harms MP, Babb C, Nishino T, Barch D. The effects of poverty on childhood brain development: the mediating effect of caregiving and stressful life events. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167:1135–42. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hetzner NP, Johnson A, Brooks-Gunn J. Poverty, effects of on social and emotional development. Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning. 2011:77. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luby J, Heffelfinger A, Koenig-McNaught AL, Brown K, Spitznagel E. The preschool feelings checklist: A brief and sensitive screening measure for depression in young children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:708–17. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000121066.29744.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luby J, Heffelfinger A, Mrakrotsky C, Hildebrand T. Preschool Feelings Checklist. St. Louis, MO: Washington University School of Medicine; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luby JL. Early childhood depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:974–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08111709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egger H, Ascher B, Angold A. Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA): Version 1.1. Durham, NC: Center for Developmental Epidemiology, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Angold A, Costello E. A test-retest reliability study of child-reported psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA-C) Psychol Med. 1995;25:755–62. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angold A, Costello E. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:39–48. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts E, Walter B, Angold A. Test-Retest Reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:538–49. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts E, Walter BK, Angold A. Test-retest reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:538–49. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costello EJ, Angold A, March J, Fairbank J. Life events and post-traumatic stress: the development of a new measure for children and adolescents. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1275–88. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luby J, Belden AC. Clinical characteristics of bipolar vs. unipolar depression in preschool children: an empirical investigation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1960–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. Am Psychol. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carskadon MA, Acebo C. A self-administered rating scale for pubertal development. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14:190–5. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maxwell ME. Manual for the Family Interview for Genetic Studies (FIGS) Bethesda, MD: Clinical Neurogenetics Branch, Intramural Research Program, National Insititute of Mental Health; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carmichael-Olson H, Greenberg M, Slough N. Manual for the Waiting Task. 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole PM, Teti LO, Zahn-Waxler C. Mutual emotion regulation and the stability of conduct problems between preschool and early school age. Dev Psychopathol. 2003;15:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suomi SJ, van der Horst FC, van der Veer R. Rigorous experiments on monkey love: an account of Harry F. Harlow's role in the history of attachment theory. Integr Psychol Behav Sci. 2008;42:354–69. doi: 10.1007/s12124-008-9072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis : A regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013. p. 494. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burke J, Loeber R, Lahey B, Rathouz P. Developmental transitions among affective and behavioral disorders in adolescent boys. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:1200–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.