Abstract

Objective: Linkages of renin gene polymorphisms with hypertension have been implicated in several populations with contrasting results. Present study aims to assess the pattern of renin gene polymorphisms in Bangladeshi hypertensive individuals.

Methodology: Introns 1, 9 of renin gene and 4063 bases upstream of promoter sequence of renin gene were amplified from the genomic DNA of the total 124 (hypertensive and normotensive) subjects using respective primers. Polymerase chain reaction-based restriction fragment length polymorphisms were performed using BglI, MboI and TaqI restriction enzymes.

Results: Homozygosity was common in renin gene regarding BglI (bb=48.4%, Bb=37.9%, BB=13.7%, χ2 =1.91, P>0.05), TaqI (TT=81.5%, Tt=14.5%, tt=4.0%, χ2 =7.50, P<0.01) and MboI (mm=63.7%, Mm=32.3%, MM=4.0%, χ2=0.00, P>0.05) polymorphisms among total study population. For BglI and TaqI genotype distribution, hypertensive subjects (BglI: χ2 =6.66, P<0.05; TaqI: χ2 = 10.28, P<0.005) significantly deviate from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium law compared to normotensive subjects (BglI: χ2=0.51, P>0.05; TaqI: χ2=0.20, P>0.05). On the other hand, with respect to MboI polymorphisms of renin gene, only normotensive subjects deviate from the law (patients: χ2=1.28, P>0.05; vs controls: χ2=6.81, P<0.01). In the context of allelic frequency, common T allele was clearly prevalent (T frequency=0.86, t frequency = 0.14) for TaqI, but rare alleles b and m were more frequent for both BglI (b frequency=0.69, B frequency=0.31) and MboI (m frequency=0.80 M frequency=0.20) polymorphisms, respectively.

Conclusion: Thus, we report that Bangladeshi hypertensive subjects did not show any distinct pattern of renin gene polymorphisms compared to their healthy control subjects with regard to their genotypic and allelic frequencies.

Keywords: Renin gene polymorphism, genetic variation, hypertension, renin, BglI polymorphism, TaqI polymorphism, MboI polymorphism, association analysis, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Introduction

Hypertension is a complex multifactorial disorder with genetic, environmental and demographic factors contributing to its prevalence 1. Studies have shown that about 90-95% of cases are primary hypertension, with high blood pressure and without recognizable or explicable risk factors 2. Hypertension is related to high blood pressure which is one of the contributing factors for the onset of macrovascular complications such as myocardial infarction, stroke and end-stage renal disease. Components of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) are the important factors that regulate body's blood pressure homeostasis and dysfunction of this system leads to hypertensive phenotypes 3-5. There are also several associated causes responsible for the instigation of high blood pressure for example, age, obesity and factors like alcohol consumption, smoking 6-8. However, genetic factors also account for the initiation of variable ranges of high blood pressure in different populations. Also, genes of RAAS are of particular interest to find out the gene loci associated with hypertension. Among them, renin has always got top priority for being the key enzyme 9-11.

Animal model studies have clearly demonstrated that development of hypertension is associated with the variations in blood pressure controlling renin gene 12. To find out an association of genetic predisposition with hypertension in human, several polymorphisms within renin gene or near its promoter sequences have been reported with inconsistent results 13-16. BglI dimorphism 15 and BglI B allele in renin gene 17 was found to be associated with increased risk of developing essential hypertension, while Naftilan et al. 14 did not find such relationship. Study with Chinese population revealed that hypertension is more strongly associated with HindIII polymorphisms of renin gene than BglI 18. Another study conducted among the rural residents of Beijing, China and urban Tibetan individuals confirmed that prevalence of hypertension is related to TaqI polymorphisms of 4063 bp upstream of renin gene promoter 19. Moreover, MboI dimorphism in intron 9 of the human renin gene is strongly associated with essential hypertension 20.

Developing countries are more likely to face burden of chronic non-communicable diseases in near future due to increased life expectancy as well as demographic transition 21. Of these diseases, hypertension is one of the most important threatable causes of mortality and morbidity in the elderly population 21. On the other hand, representative data on the prevalence of hypertension in a Bangladeshi population are insufficient. A study reported that prevalence of hypertension in adults is 11.3% in Dhaka only 22. Further, migrant Bangladeshis had greater risk for hypertension compared to the Europeans and other migrant South Asians 23. It is important to reveal the molecular mechanism of blood pressure regulation. This will help in pharmacological aspects concerning the fundamental gene therapy based specific treatment to the needs of the patient. However, studies on the possible genetic predisposition to hypertension among Bangladeshi population in the context of renin gene polymorphisms are lacking. Thus, the objectives of this study was to investigate the pattern of renin gene polymorphism among the Bangladeshi hypertensive and normotensive subjects by analyzing the PCR-based BglI, TaqI and MboI restriction fragment length polymorphisms.

Methods and Materials

Study subjects and collection of blood samples

A total of 66 hypertensive unrelated Bangladeshi individuals who attended in the outdoor of the cardiology department of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU) and Appollo hospitals, Dhaka were enrolled in this study. Control subjects (n = 58) such as university and hospital personnels, office staffs and post-doc fellows willingly donated their blood for the study. The study was conducted according to the guidelines set by the ethical review board of the faculty of Biological Science, University of Dhaka. Blood pressure of each individual was measured at sitting position. People having systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg (according to World Health Organization) were considered as the hypertensive subjects. Status of the patients or grading of hypertension considering the severity of patients was not taken into consideration in the study. Patients with diabetes, chronic kidney disease or any other major renal diseases, hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HbsAg) positive were excluded from this study. The control subjects had no major health complications. Five to six milliliter of blood was collected from each individual. Plasma samples were used to analyze total cholesterol using standard enzymatic-colorimetric methods.

Rationale behind choosing BglI, MboI and TaqI restriction sites

The human renin gene consists of 10 exons and 9 introns 24. The BglI and MboI restriction sites are present at the first and ninth introns of renin gene, respectively and TaqI restriction site is present at the 4063 bases upstream of the promoter sequence. Variation in these sites, especially in BglI and TaqI, (considered to be the transcription factor binding sites) could affect the functional association of renin gene with fluid homeostasis i.e., blood pressure leading to hypertension. Besides, different literatures regarding the association of renin gene polymorphisms with hypertension among Asians, Europeans and Americans have indicated that almost all of the studies have been carried out giving emphasis on BglI, MboI and TaqI restriction fragment renin gene polymorphisms. Though some of them found strong association between polymorphism and hypertension, however, many of them did not. As this is the first study on renin gene polymorphism among Bangladeshi population, we were also interested concerning BglI, MboI and TaqI restriction sites present in renin gene to observe their association with hypertension.

Extraction of genomic DNA

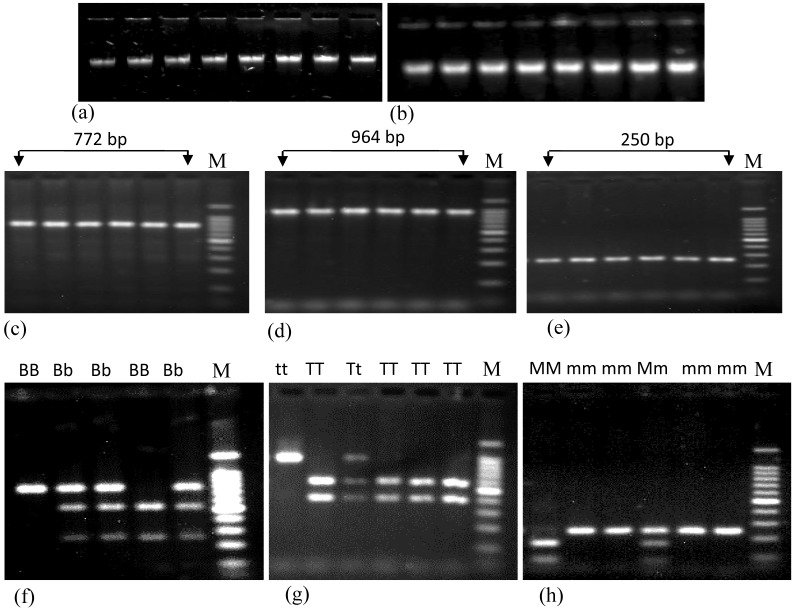

Genomic DNA was extracted by organic extraction procedure from cellular fraction of blood 25. The quantity and level of purification of extracted DNA was measured using NanoDrop (NanoDrop1000, US). The average concentration of extracted DNA was 357±17.88 ng/μL. This method generates purified DNA with an average value of 260/280 ratio was 1.79 and of 260/230 ratio was 1.57 in case of total study subjects. Extracted DNA samples were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis to determine the quality of DNA and band in Fig. 1a and 1b did not show any variation.

Figure 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis showing the genomic DNA and PCR products of renin gene having different polymorphisms. Figures a and b represent the genomic DNA extracted from both control and patient subjects, respectively. Figures c, d and e represent PCR products containing BglI, TaqI and MboI polymorphisms of renin gene. Figures f, g and h represent the restriction digestion products of amplified region using BglI, TaqI and MboI restriction enzymes respectively. Here, BB, Bb and bb; TT, Tt and tt; and MM, Mm and mm represent three different genotypes of BglI, TaqI and MboI RFLP of renin gene; M (marker) represents 100 bp ladders. In case of BglI polymorphism, size of digested PCR products are 515 bp and 257 bp; for TaqI polymorphism these are 570 bp and 394 bp; for MboI polymorphism these are 171 bp and 79 bp.

Polymerase chain reaction and restriction digestion of PCR products

To perform polymerase chain reactions, 50 μL of reaction mixture was prepared using 10 mM dNTPs, 100 μM of forward and reverses primer (specific for renin gene) and 1000 Unit of Taq DNA polymerase. PCR conditions applied for the amplification of respective regions have been presented in Table 1. PCR products were subjected to restriction digestion using BglI, TaqI and MboI according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol with minor modifications. Briefly, 2.0μL restriction enzyme buffer (10X buffer), 0.4μL bovine serum albumin (10 μg/ μL), 0.6μL restriction enzyme (1000 Unit), 7 μL deionized water and 10 μL of PCR product (1μg/μL) were mixed gently and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C for restriction digestion by BglI and MboI and, 65°C for TaqI digestion. Digested products were evaluated by agarose gel electrophoresis using 100 bp ladder as standard.

Table 1.

Conditions applied to perform polymerase chain reaction for the determination of different polymorphisms of renin gene.

| Sequence site in renin gene | Primer sequences Forward primer (FP) & Reverse primer (RP) |

PCR conditions | Size of PCR products (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4063 bases upstream of start codon of renin gene | FP: 5'GCTGTCTTCTGGTGGTACTGCC3' RP:5'TGCTGGCCATGAACTGGTTCTAGC3' |

95°C-5m (95°C-45s 60°C-30s 72°C-1m30s)×30 72°C-6m | 964 |

| within intron 1 of renin gene | FP:5'GGGGAAGCAGCTTGATATCGTGG3' RP: 5'CTAGGCTGGAGCTCAAGCGATC3' |

95°C-5m (92°C-30s 60°C-30s 72°C-30s)×30 72°C-4m | 772 |

| within intron 9 of renin gene | FP: 5'GAGGTTCGAGTCGGCCCCCT3' RP: 5'TGCCCAAACATGGCCACACAT3' |

94°C-5m (94°C-30s 68°C-30s 72°C-30s 72°C-5m)×30 | 250 |

Data analyses

The results were expressed as mean (±SD) and to compare the differences between different variables from the control and hypertensive subjects, independent Student's t-test was performed. Multivariate analyses were also performed using different parameters as independent variables (e.g., age, gender, SBP, DBP) to find out their association with genotypic variations of renin gene. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Allele frequencies were determined by Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium calculator using the method developed by Rodriguez et al. 26.

Results

Anthropometric data of the study subjects

The anthropometric and biochemical details of the study subjects are presented in Table 2. The mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were significantly higher (P < 0.001) in the hypertensive (150.5±15.8 and 94.0±13.9 mmHg, respectively) compared to that of the normotensive subjects (115.0±5.5 and 77.2±4.5 mmHg, respectively). The levels of total plasma cholesterol, random blood glucose, plasma creatinine and total protein of the normotensive and hypertensive subjects were 166.8±38.1 vs 178.8±5.6 mg/dL; 112.9±10.1 vs 120.9±9.2 mg/dL; .0.73±0.18 vs 0.99±0.08 mg/dL and 6.7±0.85 and 6.8±0.90 mg/dL, respectively.

Table 2.

Anthropometric and biochemical data of control and hypertensive subjects.

| Total protein mg/dL | 6.7 ± 0.85 | 6.8 ± 0.90b |

| Creatinine mg/dL | 0.73 ± 0.18 | 0.99 ± 0.08b |

| Random plasma glucose mg/dL | 112.9 ± 10.1 | 120.9 ± 9.2b |

| Total Cholesterol mg/dL | 166.8 ± 38.1 | 178.8 ± 5.6b |

| DBP mmHg | 77.2 ± 4.5 | 94.0 ± 13.9a |

| SBP mmHg | 115.0 ± 5.5 | 150.5 ± 15.8a |

| BMI | 21.1 ± 8.5 | 23.5 ±2.4b |

| Age years | 46.2 ± 5.6 | 35.3 ± 7.9 |

| Gender M/F | 38/20 | 47/19 |

| Sample size | 58 | 66 |

| Subjects | Normotensive | Hypertensive |

a p < 0.001 (SBP and DBP: hypertensive vs normotensive). b Not significant.

Evaluation of products derived from PCR and restriction digestion

Both PCR and restriction enzyme digested products were subjected to run on a 1.8% agarose gel Fig. 1c, 1d and 1e represent the PCR products of renin gene containing BglI, TaqI and MboI polymorphisms, respectively and Fig. 1f, 1g and 1h represent the digested PCR products with respective restriction enzymes. Sizes of the DNA bands were confirmed using 100 bp DNA ladder (Promega, USA).

Genotypic and allelic frequencies

The respective frequency of the BglI, TaqI and MboI genotype in study subjects is given in Table 3. For BglI and TaqI genotype distribution, hypertensive subjects (BglI: χ2 =6.66, df=2, P<0.05; TaqI: χ2 = 10.28, df =2, P<0.005) significantly deviate from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium law compared to normotensive subjects (BglI: χ2 =0.51, df =2, P>0.05; TaqI: χ2 = 0.2, df =2, P>0.05). On the other hand, with respect to MboI polymorphisms of renin gene, only normotensive subjects deviate from the law (patients: χ2 =1.28, df =2, P>0.05; vs controls: χ2 =6.81, df =2, P<0.01). Frequency distribution among the study subjects have been shown in Table 4. Common T allele was found to be prevalent (T frequency = 0.86, t frequency = 0.14) for TaqI, but rare alleles b and m were more frequent for both BglI (b frequency = 0.69, B frequency = 0.31) and MboI (m frequency = 0.80 M frequency = 0.20) polymorphisms, respectively among total study subjects.

Table 3.

Genotype distribution of BglI, TaqI and MboI RFLP of renin gene in both control and hypertensive subjects.

| Study subjects | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Renin genotypes | All | Normotensive | Hypertensive |

| BglI genotype frequency | |||

| BB | 13.7 (17) | 12.1 (7) | 15.2 (10) |

| Bb | 37.9 (47) | 50.0 (29) | 31.8 (21) |

| bb | 48.4 (60) | 37.9 (22) | 53.0 (35) |

| TaqI genotype frequency | |||

| TT | 81.5 (101) | 91.4 (53) | 77.3 (51) |

| Tt | 14.5 (18) | 8.6 (5) | 16.7 (11) |

| Tt | 4.0 (5) | 0 | 6.0 (4) |

| MboI genotype frequency | |||

| MM | 4.0 (5) | 0 | 6.0 (4) |

| Mm | 32.3 (40) | 41.4 (24) | 28.8 (19) |

| Mm | 63.7 (79) | 58.6 (34) | 65.2 (43) |

Table 4.

Distribution of allele frequencies of BglI, TaqI and MboI renin gene polymorphisms in normotensive and hypertensive subjects.

| Alleles | All | Normotensive | Hypertensive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BglI polymorphism | ||||

| B-allele | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.31 | |

| b-allele | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.69 | |

| TaqI polymorphism | ||||

| T-allele | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.86 | |

| t-allele | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.14 | |

| MboI polymorphism | ||||

| M-allele | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | |

| m-allele | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.80 | |

Renin BglI, TaqI and MboI genotype distributions were evaluated in relation to the levels of SBP and DBP (Table 5). There was no statistically significant difference between blood pressure values in relation to any of the three genotypes among either normotensive or hypertensive subjects. Neither the pooled data of both normotensives and hypertensives could show any significant association between the genotype distributions with the blood pressure.

Table 5.

Values of SBP and DBP (mean±SD) were set apart according to the renin BglI, TaqI and MboI genotypes. Parentheses in each cell indicate the number of the participants.

| Genotypes | Systolic blood pressure | Diastolic blood pressure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT | HT | All | NT | HT | All | |

| BglI polymorphism | ||||||

| BB | 120.25±5.73 (7) | 145 ± 12.9 (10) | 134.0±15.65 (17) | 78.0 ± 2.94 (7) | 92.5 ± 10.41 (10) | 86.05±10.11 (17) |

| Bb | 120.7 ± 7.36 (29) | 163.33±8.16 (21) | 135.32±8.2 (50) | 77.0±5.0 (29) | 105.0±6.0 (21) | 88.64±3.39 (50) |

| bb | 151.67±12.5 (22) | 116.0±11.32 (35) | 144.79±7.96 (57) | 76.67±4.57 (22) | 101.33±8.95 (35) | 92.07±4.09 (57) |

| TaqI polymorphism | ||||||

| TT | 117.95±7.1 (53) | 155.91±15.85 (51) | 117.95±20.99 (104) | 76.86±3.53 (53) | 102.0±13.54 (51) | 76.86±13.61 (104) |

| Tt | 119.0± 12.72 (5) | 148.57±14.63 (11) | 142.57±20.19 (16) | 75.5±6.36 (5) | 95.0 ±12.91 (11) | 93.71±13.78 (16) |

| Tt | 0 | 151.67±10.41 (4) | 151.67±10.41 (4) | 0 | 103.33±6.66 (4) | 103.33±6.66 (4) |

| MboI polymorphism | ||||||

| MM | 0 | 146.33±11.80 (4) | 146.33±11.80 (4) | 0 | 95.67±5.1 (4) | 95.67±5.1 (4) |

| Mm | 120.67±8.96 (24) | 146.67±20.82 (19) | 120.67±8.96 (43) | 77.0±6.1 (24) | 98.33±14.43 (19) | 77.0±6.08 (43) |

| mm | 122.0±6.24 (34) | 143.33±5.77 (43) | 120.0±6.24 (77) | 78.0±1.73 (34) | 94.33±1.15 (43) | 78.0±1.73 (77) |

NT: Normotensive and HT: Hypertensive subjects.

Discussion

The screening of variations within the renin gene to assess its linkage with high blood pressure i.e., hypertension was the main objective of the present study. The linkage and sib-pair linkage analysis and association studies have laid the ground work to evaluate the effects of genetic variations in renin gene in human population. However, the results of various sib-pair analyses have been inconsistent in clearly linking nucleotide variations of renin gene as the appropriate cause of hypertension 27-29. Numerous studies in different ethnic population have focused attention on renin intronic polymorphisms, such as HindIII, BglI and MboI as well as the promoter TaqI polymorphism that varied greatly among different reports 13-20, 30-38. To our knowledge this is the first study carried out to determine the renin gene restriction fragment length polymorphism among Bangladeshi hypertensive and normotensive subjects. This study revealed that homozygosity (both for common and rare alleles) was common in renin gene regarding BglI (bb=48.4%, Bb=37.9%, BB=13.7%, χ2 =1.91, P>0.05), TaqI (TT=81.5%, Tt=14.5%, tt=4.0%, χ2 =7.50, P<0.01) and MboI (mm=63.7%, Mm=32.3%, MM=4.0%, χ2 =0.00, P>0.05) polymorphisms among total population (Table 3).

Renin gene locus has been studied for essential hypertension using hypertensive rat models (12, 39]. In human, the association of BglI dimorphism in renin gene with hypertension in different populations 15, 20, 32 has been demonstrated, while others fail to establish such association 14, 30. On the other hand, Berge and Berg 31 in a study with Norwegian population demonstrated that BglI restriction fragment length polymorphism at the renin locus has neither the "level gene" nor "variability gene" effects on blood pressure. Allelic frequency of BglI renin gene polymorphism in present study subjects (either hypertensive or normotensive) showed that b allele (rare homozygous) was more prevalent compare to B allele (common homozygous) whereas, a meta-analysis of the case-control association studies with four populations demonstrated that renin gene BglI B allele is associated with increased risk of developing essential hypertension 17.

TaqI polymorphism is located in 4063 bases upstream of renin gene and change in single nucleotide may prevent its expression. The presence of a TaqI site in renin gene has been reported to be correlated with lower values of plasma renin activity and higher diastolic blood pressure 32. Studies 19, 38 proposed a strong association of TaqI polymorphism with hypertension and found that the frequencies of TaqI t allele were almost similar in two groups of Chinese study population which were lower compared to Caucasian European (13.75%) and Afro-Caribbean (28.45%) populations 40, 41. In current study, the frequency of T allele was higher than the frequency of t allele and showed homozygosity (TT) as genotype frequency follows the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium law. Our findings revealed that genotype frequency with rare homozygous (tt genotype) were lacking in healthy subjects who had normal blood pressure compared to those 6.0% hypertensive subjects.

The distribution of BglI and TaqI renin gene frequencies in the normotensive subjects were found to be in agreement with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, which indicated suitable selection of study subjects. Ahmad et al. 20 and Frossard et al. 32 also found that the genotype frequencies of their normotensive subjects followed Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. On the other hand, the genotype distribution in the hypertensive group of the present study did not follow the equilibrium rule. This disequilibrium in this group of study subjects could be due to the presence of other loci that might be close to either of the BglI or TaqI polymorphic sites which have strong influence on blood pressure and are strongly linked to the these sites. Also, it should be considered that being a part of the intronic sequences these sequences might be very unlikely to have produced such a strong effect by their own. In the light of this groundwork, it could be portrayed that associations of genotype frequencies of BglI and TaqI renin gene polymorphisms with SBP and DBP are lacking in the study subjects (Table 5) though the SBP and DBP varied significantly between normotensive and hypertensive subjects (Table 2).

Due to its location within intron 9, MboI RFLP probably does not represent a functional genetic variation. However, genetic variation in this region showed strong positive association with hypertension in different population groups 31, 33 while others did not find such association 36, 42. Okura et al. 37 were the first to show a positive association between renin gene MboI RFLP and essential hypertension in Japanese population using linkage disequilibrium with this site or in a nearby gene. One of the possible explanations for this variable pattern of association could be the involvement of more than one gene, with none of the involved genes having a strong influence or penetrance, as is expected for a complex polygenic disorder. Frossard et al. 31, 32 reported frequencies of 0.64 and 0.36 for the MboI G and MboI A alleles in normotensive subjects, whereas the allele frequencies in the hypertensive group were 0.49 and 0.51, respectively. In the present study, the allelic frequencies were 0.79 and 0.80 for m and 0.21 and 0.20 for M alleles, respectively for normotensive and hypertensive subjects. In this case, the MboI genotype frequencies of hypertensive subjects followed the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium law while the normotensive subjects did not follow this rule. Interestingly, the observed frequency of MM genotypes (homozygous for common allele at each locus) were lacking among the normotensive subjects enrolled in the present study while 6.0% of the hypertensive subjects showed such genotypic frequency. Moreover, we did not find any association between the MboI genotypic frequencies of the normotensive and hypertensive subjects with their respective SBP and DBP (Table 5).

Genetic profiling of the functional genes not only helps to investigate a specific disease but also to understand the disease propensity within a particular population that may ultimately be of assistance to the clinicians and physicians for prescribing personalized medicine. Brugts et al. in their series of articles 43-46 suggested a broad description of the role of ACE inhibition in the treatment of patients with atherosclerosis. In a substudy of the well-described EUROPA trial with 9454 patients suffering from stable coronary artery disease 47, a genetic analysis was performed (PERGENE study). All these data within their limitations serve as substitute for the functional variant which are mostly rare and are not well covered by traditional genome-wide association studies.

Previous study in Bangladeshi hypertensive population demonstrated that among the three DD, II and ID angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) gene variants, the DD genotype was associated with the highest value of the mean systolic blood pressure and mean diastolic blood pressure in men, but not in women 48. Despite the considerable controversy regarding the existence and importance of ethnic differences in genetic effects for complex diseases, it seems evident that genetic markers for proposed gene-disease associations vary in frequency across populations. Thus, it is important to construct a database of polymorphisms related to hypertension in each ethnic group as suggested by Izawa et al. 49. In humans, elevated blood pressure is associated with increased risk of vascular diseases including myocardial infarction, stroke and coronary artery disease. The variance in blood pressure and its regulation followed by cardiovascular disease susceptibility within populations sharing a common environment indicates that there are genetic as well as cultural determinants of risk 50. Some ethnic groups may be at particular risk of high blood pressure exposed to the same urban environment suggesting involvement of genetic factors. While, changes in lifestyle predominantly the diet and physical activity play an important role in the growing rates of hypertension leading to cardiovascular related complications in developing countries 50. The Asian Indians residing in Singapore have three times higher rates of myocardial infarction than that of Chinese population despite exposure to a similar environment 51. On the other hand, individuals within the same family, may become hypertensive due to different combinations of genes or due to exposure to different environment including life style, dietary habit or lack of physical activity 52. Thus, it has been suggested that the possible reasons accounting for the controversy regarding ethnic differences are neither only for genetic variations nor for other risk associated factors alone rather due to complex interplay between environment, diet, physical activity and genetic variations 53.

It is indeed a matter of argument regarding the fact that why Bangladeshi people are lacking an association between the renin gene polymorphisms and hypertension in the current study while other Asian people like Chinese, Japanese, and United Arab Emiratis displayed such association. Different studies postulated that South Asians have highest levels of subclinical atherosclerosis than the Chinese 54 and among the South Asians, Bangladeshis have lowest rate of hypertension than Indians and Pakistanis 55. These studies clearly demonstrate that neither the genetic nor the other associated factors alone play role in initiating hypertension with increased blood pressure along with different cardiovascular associated phenotypic expression in Bangladeshi people compare to other Asian people; even compare to other South Asian Indians and Pakistanis. Interestingly, contrasting results regarding the association of MboI restriction fragment length polymorphism of renin gene have been reported even in the same Japanese population 36, 37. Even with the small genetic diversity, Japanese people showed two clusters with different genotypic variations 56-58 which might be the reason of two different MboI renin gene polymorphism data 36, 37. However, rather than excluding the possibility of Indo-Aryan migration 59, different studies suggest that the genetic affinities of both Indian ancestral parts are the result of multiple gene pools that flows over the course of thousands of years, with Indo-Aryan extension into the subcontinent 60. Thus, these accumulating data suggest that genetic diversity along with environmental, dietary, cultural as well as genome-wide signals of positive selection from the ancestors might have collectively contributed to the phenotypic diversity in South Asians especially in Bangladeshi people.

The present study has to be taken under consideration within the context of its limitations. It is to mention here that this research work only deals with the association study (irrespective of gender) between blood pressure and the genetic variation of the 3 restriction sites within the renin gene and near its promoter sequence. However, multivariate analyses using age and gender as independent variable respectively also revealed lack of association of renin gene polymorphism with blood pressure. Here, we report that, Bangladeshi hypertensive subjects did not show any distinct pattern of renin gene polymorphisms compared to their healthy counterparts with regard to their genotypic and allelic frequencies, though the rare homozygous in case of TaqI (tt genotype) and common homozygous in case of MboI (MM genotype) are lacking in the normotensive subjects.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the grant provided by Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, University Grants Commission, Bangladesh and Biotechnology Research Center, University of Dhaka. Authors would also like to express their sincere thanks and heartfelt gratitude to Professors Dr. Mustafizur Rahman, Dr. Haseena Khan and Dr. Zeba Islam Seraj for their intellectual and technical supports during this research work.

References

- 1.Tanira MO, Al Balushi KA. Genetic variations related to hypertension: a review. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:7–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oparil S, Haber E. The renin-angiotensin system (first of two parts) N Engl J Med. 1974;291:389–401. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197408222910805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corvol P, Jeunemaitre X, Charru A, Kotelevtsev Y, Soubrier F. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in blood pressure regulation and in human hypertension: new insights from molecular genetics. Rec Prog Horm Res. 1995;50:287–308. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571150-0.50017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters J. Molecular basis of human hypertension: the role of angiotensin. Baill Clin Endocrin Metab. 1995;9:657–678. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(95)80672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamura K, Umemura S, Fukamizu A, Ishii M, Murakami K. Recent advances in the study of renin and angiotensinogen genes: from molecules to the whole body. Hypertens Res. 1995;18:7–18. doi: 10.1291/hypres.18.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thadhani R, Camargo CA, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rimm EB. Prospective study of moderate alcohol consumption and risk of hypertension in young women. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:569–574. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pi-Sunyer FX. Health implications of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53:1595S–1603S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.6.1595S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He J, Whelton PK. Epidemiology and prevalence of hypertension. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81:1077–1097. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobori H, Ozawa Y, Suzaki Y, Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Nishiyama A, Shoji T, Cohen EP, Navar LG. Young Scholars Award Lecture: Intratubular angiotensinogen in hypertension and kidney diseases. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:541–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oparil S, Haber E. () The renin-angiotensin system (second of two parts) N Engl J Med. 1974;291:446–457. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197408292910905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carretero OA, Oparil S. Essential hypertension. Part I: definition and etiology. Circulation. 2000;101:329–335. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rapp JP, Dene H, Wang SM. Restriction fragment length polymorphisms for the renin gene in Dahl rats. J Hypertens. 1989;7:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsubara M. Genetic determination of human essential hypertension. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2000;192:19–33. doi: 10.1620/tjem.192.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naftilan AJ, Williams R, Burt D, Paul M, Pratt RE, Hobart P, Chirgwin J, Dzau VJ. A lack of genetic linkage of renin gene restriction fragment length polymorphisms with human hypertension. Hypertension. 1989;14:614–618. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.14.6.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frossard PM, Lestringant GG, Malloy MJ, Kane JP. Human renin gene BglI dimorphism associated with hypertension in two independent populations. Clin Genet. 1999;56:428–433. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.560604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris BJ, Griffiths LR. Frequency in hypertensives of alleles for a RFLP associated with the renin gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;150:219–224. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu W, Qi Y, Guo S, Gao P, Zhu D. Association of renin BglI polymphism with essential hypertension: a meta-analysis involving 1811 cases and 1626 controls. Clin Exp Hypertension. 2010;32:431–438. doi: 10.3109/10641961003686419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang YP, Zhu X, Yan D, Weder A, Cooper R, Luke A, Kan D, Chakravarti A. Associations between hypertension and genes in the renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension. 2003;41:1027–34. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000068681.69874.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qi Y, Niu W, Cen W, Cui C, Zhuoma C, Zhuang L, Cai D, Li G, Zhou W, Hou S, Qiu C. Strong association of the renin TaqI polymorphism with essential hypertension in Chinese Han and Tibetan populations. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21:907–910. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmad U, Saleheen D, Bokhari A, Frossard PM. Strong association of a renin intronic dimorphism with essential hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2005;28:339–344. doi: 10.1291/hypres.28.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perkovic V, Huxley R, Wu Y, Prabhakaran D, MacMahon S. The Burden of Blood Pressure-Related Disease: A Neglected Priority for Global Health. Hypertension. 2007;50:991–997. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.095497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaman MM, Yoshiike N, Rouf MA, Syeed MH, Khan MR, Haque S, Mahtab H, Tanaka H. Cardiovascular risk factors: distribution and prevalence in a rural population of Bangladesh. J Cardiovasc Risk. 2001;8:103–108. doi: 10.1177/174182670100800207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sayeed MA, Banu A, Haq JA, Khanam PA, Mahtab H, Azad Khan AK. Prevalence of hypertension in Bangladesh: effect of socioeconomic risk factor on difference between rural and urban community. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2002;28:7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyazaki H, Fukamizu A, Hirose S, Hayashi T, Hori H, Ohkubo H, Nakanishi S, Murakami K. Structure of the human renin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5999–6003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.19.5999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rapid Extraction of High Quality DNA from Whole Blood Stored at 4ºC for Long Period. Iranpur MV, Esmailizadeh AK; http://www.protocol-online.org/cgi-bin/prot/page.cgi?g=print_page/4175.html. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez S, Gaunt TR, Ian NMD. Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Testing of Biological Ascertainment for Mendelian Randomization Studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:505–514. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeunemaitre X, Rigat B, Charru A, Houot AM, Soubrier F, Corvol P. Sib pair linkage analysis of renin gene haplotypes in human hypertension. Hum Genet. 1992;88:301–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00197264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niu T, Xu X, Cordell HJ, Cordell HJ, Rogus J, Zhou Y, Fang Z, Lindpaintner K. Linkage analysis of candidate genes and gene-gene interactions in Chinese hypertensive sib pairs. Hypertension. 1999;33:1332–1337. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.6.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caulfield M, Lavender P, Newell-Price J, Farrall M, Kamdar S, Daniel H, Lawson M, De Freitas P, Fogarty P, Clark A J. Linkage of the angiotensinogen gene to essential hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1629–1633. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berge KE, Berg K. No effect of a BglI polymorphism at the renin (REN) locus on blood pressure level or variability. Clin Genet. 1994;46:436–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1994.tb04413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frossard PM, Kane JP, Malloy MJ, Bener A. Renin gene MboI dimorphism is a discriminator for hypertension in hyperlipidaemic subjects. Hypertens Res. 1999;22:285–289. doi: 10.1291/hypres.22.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frossard PM, Lestringant GG, Hughes PF. Correlations between RFLPs of the human renin gene locus and clinical variables of blood pressure regulation. Biogenic Amines. 1995;11:313–324. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frossard PM, Lestringant GG, Elshahat YI, John A, Obineche EN. An MboI two-allele polymorphism may implicate the human renin gene in primary hypertension. Hypertens Res. 1998;21:221–225. doi: 10.1291/hypres.21.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frossard PM, Malloy MJ, Lestringant GG, Kane JP. Haplotypes of the human renin gene associated with essential hypertension and stroke. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15:49–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.West MJ, Summers KM, Burstow DJ, Wong KK, Huggard PR. Renin and angiotensin-converting enzyme genotypes in patients with essential hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1994;21:207–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1994.tb02497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu Y, Katsuya T, Asai T, Fukuda M, Inamoto N, Iwashima Y, Sugimoto K, Rakugi H, Higaki J, Ogihara T. Lack of correlation between MboI restriction fragment length polymorphism of renin gene and essential hypertension in Japanese. Hypertens Res. 2001;24:295–298. doi: 10.1291/hypres.24.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okura T, Kitami Y, Wakamiya R, Iwata T, Hiwada K. Renin gene restriction fragment length polymorphisms in a Japanese family with a high incidence of essential hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol Suppl. 1992;20:17–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niu W, Qi Y, Hou S, Zhai X, Zhou W, Qiu C. Haplotype-based association of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system genes polymorphisms with essential hypertension among Han Chinese: the Fangshan study. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1384–1391. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832b7e0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mullins JJ, Peters J, Ganten D. Fulminant hypertension in transgenic rats harbouring the mouse Ren-2 gene. Nature. 1990;344:541–544. doi: 10.1038/344541a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deinum J, Tarnow L, van Gool JM, de Bruin RA, Derkx FH, Schalekamp MA, Parving HH. Plasma renin and prorenin and renin gene variation in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:1904–1911. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.8.1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barley J, Carter ND, Cruickshank JK, Jeffery S, Smith A, Charlett A, Webb DJ. Renin and atrial natriuretic peptide restriction fragment length polymorphisms: association with ethnicity and blood pressure. J Hypertens. 1991;9:993–996. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramachandran V, Ismail P, Stanslas J, Shamsudin N. Analysis of renin-angiotensin aldosterone system gene polymorphisms in malaysian essential hypertensive and type 2 diabetic subjects. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2009;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brugts JJ, de Maat MPM, Danser AHJ, Boersma E, Simoons ML. Individualised therapy of ACE inhibitors in stable coronary artery disease: overview of the primary results of the PERindopril GENEtic association study. Neth Heart J. 2012;20:24–32. doi: 10.1007/s12471-011-0173-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brugts JJ, de Maat MP, Boersma E, Witteman JC, van Duijn C, Uitterlinden AG, Bertrand M, Remme W, Fox K, Ferrari R, Danser AH, Simoons ML; EUROPA-PERGENE investigators. The rationale and design of the perindopril genetic association study (pergene): a pharmacogenetic analysis of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2009;23:171–181. doi: 10.1007/s10557-008-6156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brugts JJ, Isaacs A, Boersma E, van Duijn CM, Uitterlinden AG, Remme W, Bertrand M, Ninomiya T, Ceconi C, Chalmers J, MacMahon S, Fox K, Ferrari R, Witteman JC, Danser AH, Simoons ML, de Maat MP. Genetic determinants of treatment benefit of the angiotensin-converting enzyme-inhibitor perindopril in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1854–1864. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brugts JJ, Boersma E, Simoons ML. Tailored therapy of ACE inhibitors in stable coronary artery disease: pharmacogenetic profiling of treatment benefit. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11:1115–1126. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fox KM. Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the Europa study) Lancet. 2003;362:782–788. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morshed M, Khan H, Akhteruzzaman S. Association between angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene polymorphism and hypertension in selected individuals of the Bangladeshi population. Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2002;35:251–254. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2002.35.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Izawa H, Yamada Y, Okada T, Tanaka M, Hirayama H, Yokota M. Prediction of genetic risk for hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:1035–1040. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000065618.56368.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104:2746–2753. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tai SE, Tan CE. Interaction between genetic and dietary factors affecting cardiovascular risk. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2005;14:72–77. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mehta SK, Super DM, Anderson RL, Harcar-Sevcik RA, Babjak M, Liu X, Bahler RC. Parental hypertension and cardiac alterations in normotensive children and adolescents. Am Heart J. 1996;131:81–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(96)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Svetkey LP, Moore TJ, Simons-Morton DG, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Sacks FM, Ard JD, Mortensen RM, Mitchell SR, Contin PR, Kesari M. Angiotensinogen genotype and blood pressure response in the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) study. J Hypertens. 2001;19:1949–1956. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anand SS, Yusuf S, Vuksan V, Devanesen S, Teo KK, Montague PA, Kelemen L, Yi C, Lonn E, Gerstein H, Hegele RA, McQueen M. Differences in risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease between ethnic groups in Canada: the Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic groups (SHARE) Lancet. 2000;356:279–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02502-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhopal R, Unwin N, White M, Yallop J, Walker L, Alberti KG, Harland J, Patel S, Ahmad N, Turner C, Watson B, Kaur D, Kulkarni A, Laker M, Tavridou A. Heterogeneity of coronary heart disease risk factors in Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and European origin populations: cross sectional study. Br Med J. 1999;319:215–220. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7204.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haga H, Yamada R, Ohnishi Y, Nakamura Y, Tanaka T. Gene-based SNP discovery as part of the Japanese Millennium Genome Project: identification of 190,562 genetic variations in the human genome. Single-nucleotide polymorphism. J Hum Genet. 2002;47:605–610. doi: 10.1007/s100380200092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hammer MF, Karafet TM, Park H, Omoto K, Harihara S, Stoneking M, Horai S. Dual origins of the Japanese: common ground for hunter-gatherer and farmer Y chromosomes. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:47–58. doi: 10.1007/s10038-005-0322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamaguchi-Kabata Y, Nakazono K, Takahashi A, Saito S, Hosono N, Kubo M, Nakamura Y, Kamatani N. Japanese population structure, based on SNP genotypes from 7003 individuals compared to other ethnic groups: effects on population-based association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:445–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Metspalu M, Romero IG, Yunusbayev B, Chaubey G, Mallick CB, Hudjashov G, Nelis M, Mägi R, Metspalu E, Remm M, Pitchappan R, Singh L, Thangaraj K, Villems R, Kivisild T. Shared and unique components of human population structure and genome-wide signals of positive selection in South Asia. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:731–744. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium, Abdulla MA, Ahmed I, Assawamakin A, Bhak J, Brahmachari SK, Calacal GC, Chaurasia A, Chen CH, Chen J, Chen YT, Chu J, Cutiongco-de la Paz EM, De Ungria MC, Delfin FC, Edo J, Fuchareon S, Ghang H, Gojobori T, Han J, Ho SF, Hoh BP, Huang W, Inoko H, Jha P, Jinam TA, Jin L, Jung J, Kangwanpong D, Kampuansai J, Kennedy GC, Khurana P, Kim HL, Kim K, Kim S, Kim WY, Kimm K, Kimura R, Koike T, Kulawonganunchai S, Kumar V, Lai PS, Lee JY, Lee S, Liu ET, Majumder PP, Mandapati KK, Marzuki S, Mitchell W, Mukerji M, Naritomi K, Ngamphiw C, Niikawa N, Nishida N, Oh B, Oh S, Ohashi J, Oka A, Ong R, Padilla CD, Palittapongarnpim P, Perdigon HB, Phipps ME, Png E, Sakaki Y, Salvador JM, Sandraling Y, Scaria V, Seielstad M, Sidek MR, Sinha A, Srikummool M, Sudoyo H, Sugano S, Suryadi H, Suzuki Y, Tabbada KA, Tan A, Tokunaga K, Tongsima S, Villamor LP, Wang E, Wang Y, Wang H, Wu JY, Xiao H, Xu S, Yang JO, Shugart YY, Yoo HS, Yuan W, Zhao G, Zilfalil BA. Indian Genome Variation Consortium. Mapping human genetic diversity in Asia. Science. 2009;326:1541–1545. doi: 10.1126/science.1177074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]