Summary

Head-direction (HD) cells fire as a function of an animal’s directional heading in the horizontal plane during 2-D navigational tasks [1]. The information from HD cells is used with place and grid cells to form a spatial representation (cognitive map) of the environment [2,3]. Previous studies have shown that when rats are inverted (upside-down), they have difficulty learning a task that requires them to find an escape hole from one of four entry points, but can learn it when released from one or two start points [4]. Previous reports also indicate that the HD signal is disrupted when a rat is oriented upside-down [5,6]. Here we monitored HD cell activity in the two entry-point version of the inverted task and when the rats were released from a novel start point. We found that despite the absence of direction-specific firing in HD cells when inverted, rats could successfully navigate to the escape hole when released from one of two familiar locations by using a habit-associated directional strategy. In the continued absence of normal HD cell activity, inverted rats failed to find the escape hole when started from a novel release point. The results suggest that the HD signal is critical for accurate navigation in situations that require an allocentric cognitive mapping strategy, but not for situations that utilize habit-like associative spatial learning.

Results

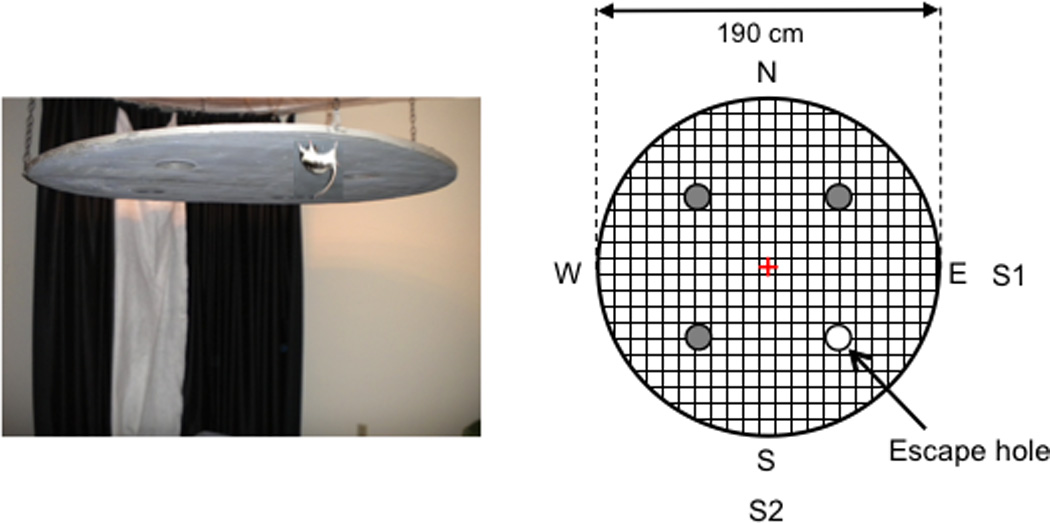

Pretraining, training, and testing of rats was conducted on a circular apparatus that was suspended from the ceiling of the experimental room (see Supplemental Methods, Figure S1, Movie S1). Rats had to locomote in an inverted position from one of two release points on the apparatus perimeter (S1, S2) and find a fixed escape hole that was located in a nearby quadrant on the platform (Fig. 1). The task took advantage of the rats’ proclivity to avoid remaining in an inverted orientation and by locomoting into the escape hole the rats could bring themselves into an upright position. Training to criterion took an average of 106 ± 19.3 trials. After the rats had learned to navigate directly to the escape hole from each start location we implanted a 16-wire drivable recording electrode array just dorsal to the anterodorsal thalamic nucleus (ADN), which is densely populated by HD cells (Taube 1995). When a HD cell was detected we recorded its activity during an 4–8 min session in a cylinder (76 cm diameter) on the floor of the room (Pre-test; rat upright). Next, we recorded cell activity on the inverted apparatus under two test conditions when the rat was in an inverted orientation. First, we conducted two test trials where the rats were released from each of the two familiar start points (Familiar-S1, Familiar-S2). Second, we tested the rats when released from a novel start location in the center of the inverted apparatus (Center). The rats encountered these three inverted test conditions on multiple occasions (mean number of test trials/cell for each session type: Familiar = 6.84 ± 1.00 trials; Novel center = 3.75 ± 0.59 trials). The nature of the navigational cues required to successfully navigate to the escape hole differed for the Familiar and Center conditions. When the inverted animals were released from a familiar test location they needed to use landmarks within the room to establish a directional bearing to the correct escape hole. They also had to discriminate their visual views between the two start locations in order to head in the correct direction (see [4] for details). During the Center condition trials, the inverted rats were placed in an unfamiliar location (the maze center) and had to use their representation of landmarks in the environment to compute their directional orientation and an accurate route to the escape hole. The Center condition trials therefore require a flexible use of the animal’s spatial representation of its environment (cognitive map) in order to chart an accurate course to the escape hole [2]. The rats encountered the three inverted test conditions (Familiar S1, Familiar S2, Center) on multiple occasions (mean number of test trials/cell for each session type: Familiar = 6.84 ± 1.00 trials; Novel center = 3.75 ± 0.59 trials). Following conclusion of the inverted trials, we performed a final test of the cell’s activity in the cylinder on the room floor (Post-test; rat upright) in order to determine if the cell’s firing properties had changed at all from the Pre-test condition as a result of the inverted trials. We successfully recorded from 16 HD cells during the Familiar condition and 12 of the same 16 cells during the Center test condition.

Figure 1. The inverted holeboard escape task.

Left, an image of the inverted apparatus suspended from the ceiling of the experimental room. The inverted apparatus was a plywood circle (190 cm dia.) containing four uniformly spaced holes (15 cm dia.; with three holes blocked off with a piece of wood) and was suspended 50 cm from the ceiling of the experimental room (Fig. 1). We positioned a floor-to-ceiling, black curtain that ran 120° along one perimeter of the inverted apparatus. A white sheet was attached to the interior of the black curtain and covered the inner 1/3 of the black curtain arc. Other prominent global objects that the rat could see, but not visible in the image (e.g., door, chair), were also in the room. Right, A “bottom-up” schematic of the inverted apparatus shows the four start locations (N = North, S = South, E = East, W = West) and each of the four escape holes. Each rat was assigned two adjacent start locations from the pool of four potential locations and different rats had different adjacent pairs of start locations. In this example of a Familiar test trial, three of the escape holes are covered with lids (gray-filled circles) and the rat would be placed at either the E (S1) or S (S2) start location to begin the trial (see text). The rat then traveled from the start location to the assigned escape hole nearest the adjacent pair of start locations. The grid represents the wire mesh screen (each square of the mesh was .635 cm2) that covered the bottom of the apparatus and was used by the rats to move from one location to the next. Center trials started from the apparatus center (red cross) and rats were placed facing random directions. Also see Figure S1 in supplement.

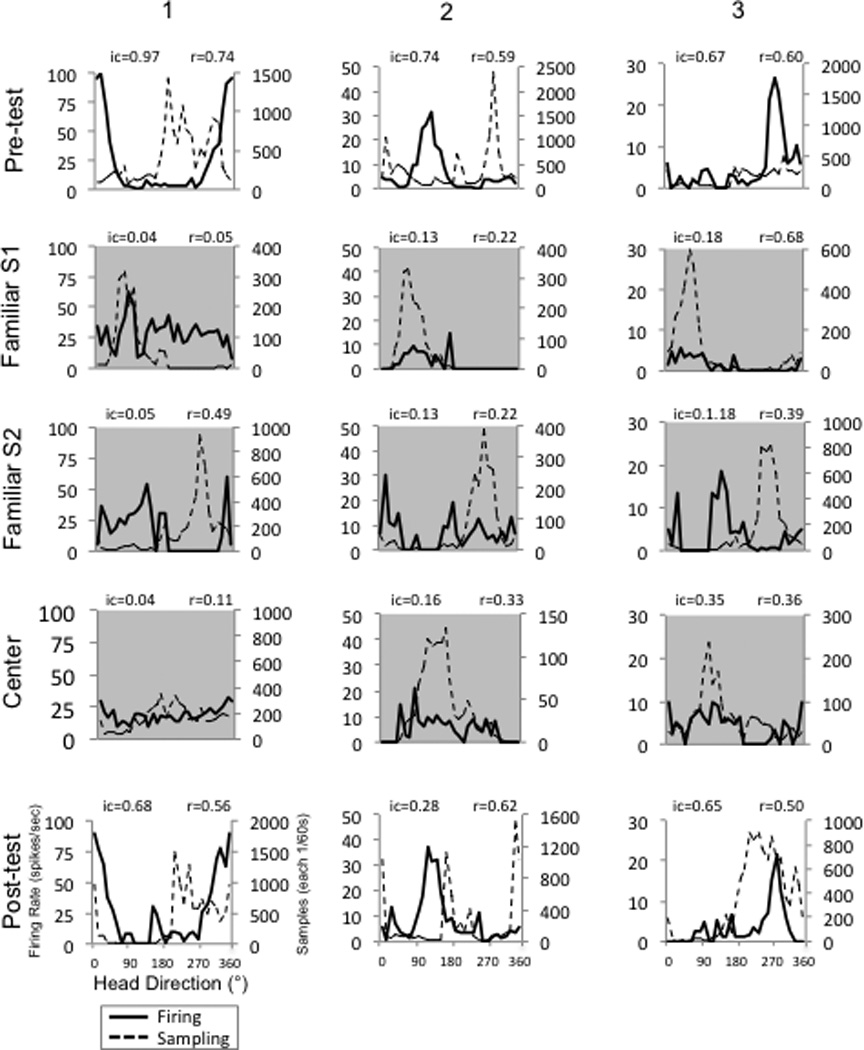

HD cells discharged at a high firing rate when the animal’s head was facing the cell’s preferred direction during the Pre-test cylinder session (Fig. 2). Peak firing rates, directional firing ranges, signal-to-noise ratios, and Rayleigh r values of the HD signals were all within ranges of values recorded from the ADN in previous studies [1] (Table 1). The firing characteristics of the cells, however, changed dramatically when we tested them during the inverted conditions (Familiar-S1, Familiar-S2, Center). All HD cells generally displayed a loss of direction-specific firing (Table 1, Fig. 2, gray shaded section). An ANOVA indicated that the mean Rayleigh r values for the three inverted conditions (Familiar-S1, Familiar-S2, and Center) were significantly less than the r values during the upright Pre-test and Post-test sessions, F(4,44) = 16.915, p=0.0001, η2= 0.971. There were a few sessions, however, which had Rayleigh r values above 0.4 (e.g., Cell 3, Familiar S1), but these sessions usually had an attenuated peak firing rate compared to the upright Pre- and Post-test sessions. Further, directional information content values were also generally low for these sessions. The mean directional information content for both Familiar sessions was significantly less than for the Pre- and Post-sessions; it was also lower for the Center sessions although the mean value did not reach significance (Table 1). Figure 3A plots a scattergram of Rayleigh r values versus directional information content across all conditions. Note that all values in the lower left quadrant formed by the two dashed lines are from the inverted conditions and that all upright values had a Rayleigh r score above 0.4. Only 2 out of 28 values from the inverted conditions had both a Rayleigh r score and a directional information content score that were above both thresholds, and again, even these two points had peak firing rates that were significantly less than the peak firing rates for the upright sessions.

Figure 2. HD cell firing characteristics during upright and inverted conditions.

The head direction vs. firing rate responses of three HD cells (columns 1–3) in three different animals during the Pre-test, Familiar S1, Familiar S2, Center, and Post-test conditions. The tuning curves depicted with a gray background indicate conditions in which the animals were tested on the inverted apparatus. Note that direction-specific firing is either absent or markedly attenuated in all the inverted conditions. Though only shown in the lower left panel, all panels have the same labels for the abscissa and ordinate. See also Figure S2.

Table 1.

Firing properties recorded from 16 HD cells across sessions.

| Condition | Peak Firing Rate (spikes/sec) |

Directional Firing Range (degrees) |

Background Firing Rate (spikes/sec) |

Signal/Noise Ratio |

Rayleigh Vector (r) |

Information Content (IC) |

Burst Index Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | 49.54 ± 8.01 | 118.05 ± 7.41 | 19.16 ± 6.68 | 11.52 ± 2.69 | 0.655 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.14 | 0.596 ± 0.04 |

| Familiar-S1 | 33.36 ± 8.86 | - | 11.52 ± 2.70 | 5.59 ± 1.31 | 0.414 ± 0.05 | 0.32 ± 0.10 | 0.498 ± 0.06 |

| Familiar-S2 | 27.34 ± 7.48 | - | 21.12 ± 9.63 | 4.68 ± 1.45 | 0.292 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.07 | 0.505 ± 0.06 |

| Center | 30.25 ± 9.63 | - | 16.82 ± 4.77 | 4.91 ± 1.69 | 0.271 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.10 | 0.548 ± 0.07 |

| Post-test | 45.19 ± 8.78 | 120.22 ± 7.43 | 14.50 ± 5.04 | 10.02 ± 2.50 | 0.618 ± 0.03 | 0.68 ± 0.10 | 0.558 ± 0.01 |

Mean values ± s.e.m. are reported for: 1) Pre-test session (upright in the cylinder on the floor), 2) inverted sessions after released from the familiar start locations (Familiar S1, Familiar S2) or the center of the apparatus, and 3) Post-test session (upright in the cylinder on the floor). Inverted conditions are shaded in gray. Because the cells lost direction-specific firing in the inverted conditions, it was not possible to calculate a directional firing range.

Figure 3. (A) information content by direction plots for each cell. (B) Trajectories (left) and paths (right) during the inverted task.

A, Rayleigh r values versus directional information content across all conditions Each data point represents the mean of the upright (Pre-, Post- test), inverted familiar (Familiar-1 & Familiar 2) and Center conditions for each cell. The dashed lines indicate threshold values above which cells are considered to contain significant direction-specific firing. B - Familiar Tests, The mean departure headings for 16 HD cells during the inverted familiar F1 and F2 conditions for animals that were released from the north (N), west (W) pair (blue solid arrows) or the south (S), east (E) pair (green arrows) of start points on the perimeter of the apparatus (as shown in Figure 1). The smaller circles indicate the position of the intended escape holes for each pair of start locations. The dashed arrows indicate the mean vector for each population of trials from their respective release points (Mean heading error° = ideal vector° − mean obtained°: N = 6.8°; W = 16.9°; S = 0.2°; E = 10.0°). The magnitude of the mean vector (r) is indicated by its length. To the right are the representative paths from rats for the three cells shown in Figure 2 for each start location (all of which have the N and W pair of start locations) during the inverted familiar F1 and F2 conditions. Each colored path corresponds to a separate trial. Two trials from each start location are shown for three different sessions. Center Tests, the mean departure headings during each of the inverted center tests for these same animals when they were released from the center of the apparatus are shown in the lower left. The color coding scheme is the same as above. The mean vectors for animals trained from the N, W and S, E start points are indicated by the dashed purple and red arrows, respectively (see above); the dark blue and light green arrows indicate the ideal headings from the center to the two escape holes. The rats encountered 45 center tests. To the right are the representative paths from the same three cells in the top right panel during the center test condition (2 paths per cell) are shown in the lower right. The blue escape hole (shown) was correct during training for these paths. See also Figure S3.

The S/N was higher for the Pre- and Post- test conditions compared to the inverted conditions. The HD cells did not show a significant change in background firing across conditions F(4)44 = 1.795, p=0.147, η2= 0.503. The background firing was distributed across all directions and was not characterized by isolated “bursts” of activity followed by quiescence, which is typical of normal HD cell activity when an animal is an upright position (see supplemental data, Figure S2). When the rats were returned to the floor of the cylinder during the Post-test session, direction-specific firing returned, and HD cells again fired when the rat’s head was oriented in the cell’s preferred direction; background firing rates also diminished and returned to Pre-test session levels (Table 1, Fig. 2). HD cell preferred firing directions were not significantly different during the Pre-test and Post-test conditions (mean change of the preferred direction = 1.04 ± 2.22°). The return of cell properties to their Pre-test levels indicates that the loss of directional firing during the inverted sessions could not be attributed to poor cell isolation.

Importantly, while direction-specific firing was disrupted during the inverted sessions, the rats continued to find the escape hole during the Familiar-S1 (n = 111) and Familiar–S2 (n = 108) sessions. V-tests confirmed that the mean heading of the rats (Fig. 3, top) from each release point (N, W, S, E) was significantly aligned with the ideal vector needed to travel from each release point to the escape hole (all ps < 0.05). Thus, despite the absence of directional activity in HD cells, rats’ performances from the two familiar release points were highly accurate (mean escape time: 12.35 ± 3.12 s) and their trajectories and paths to the escape hole were generally direct (Fig. 3B, top left, right). The mean distance of the routes from Familiar-S1 release to the goal was 38.42 ± 0.81 cm and 36.34 ± 0.76 cm from Familiar-S2 to the goal (see Figure S3). In contrast to the accurate performance from the familiar release points, all rats failed to find the escape hole when they were released from the center of the apparatus (Center sessions: n = 44; see Fig. 3B, bottom right for examples of paths). Although the rats usually did not reach the escape hole in the Center condition because they proceeded in the wrong direction and had to be rescued from falling off usually after 30 sec, we calculated the mean distance they locomoted and the time taken before they fell off. The mean distance during the Center condition trials was 44.29 ± 2.81 cm and these journeys lasted 27.40 ± 6.70 sec. V-tests confirmed that the mean headings of the rats (Fig. 3B, bottom left) were not significantly aligned with the ideal heading from the center of the apparatus to either the escape hole in the northwest or in the southeast for rats trained with the N, W and S, E start points, respectively (all ps > 0.05).

Discussion

Most studies investigating the neural mechanisms of navigation are conducted with the animal oriented upright and locomoting in a flat, two-dimensional horizontal plane [1,2] and relatively little is known about what happens to the HD signal and the corresponding spatial representation when an animal is placed in an inverted orientation. Recent research has shown that the HD signal is disrupted when the animal is positioned in an inverted plane either under 1-g or 0-g conditions [5, 6]. In addition, a recent study demonstrated that inverted rats were unable to learn to navigate to an escape hole unless they were released from one of two familiar locations [4]. When released from novel locations, they were unable to reach the escape hole, despite the presence of familiar visual landmarks within the environment and the fact that the escape hole was < 1 m from the release point. In the study that monitored HD cell activity when the animals were inverted, the animals performed a relatively simple spatial task, which only required them to move forward continually along a 1-foot strip of wire mesh in order to reach a goal box [5]. The task was not particularly challenging and could be performed without the use of a flexible, cognitive map-like strategy. Therefore, it remained to be determined whether i) a more demanding spatial task, one that required the use of distal visual cues, would enable normal direction-specific firing in HD cells, and ii) whether an animal can still engage in accurate navigation while inverted despite the absence of a normal HD signal.

Here, we found that when rats were released from either of the familiar entry points all them took direct routes to the correct hole, indicating that they were aware of their spatial relationship relative to the goal and were able to chart an accurate course to it. This accurate performance occurred in the absence of direction-specific firing in HD cells and indicates that the rats were able to adopt a strategy that did not require information from HD cells. Our previous behavioral study [4] using this same inverted task, demonstrated that rats performances were impaired when we impeded their view of surrounding room cues, suggesting that they were using visual landmarks to form a habit-like, directional associational strategy to reach the goal [7,8]. This solution utilizes the formation of associations between distal cues within the room and learning a trajectory from a familiar release point in relation to these cues. Because the rat had been trained on this task repeatedly the rats’ behavior had likely become habitual. In contrast, when the rats were released from the apparatus center, a novel start point that they had not been previously trained from, they were unable to chart an accurate trajectory to the goal, and their paths appeared random. Calculating an accurate path under these conditions requires knowledge of the spatial relationships between itself, the goal, and the surrounding room landmarks, and, additionally, an ability to flexibly use this information to derive a desired course. In other words, they need a cognitive map-like representation of the environment to perform the task [2,9]. The failure to locate the goal during the Center condition does not appear to reflect a deficit in perceiving the landmarks from the center location because over the course of training and testing the rats had substantial exposure to different views of the room. It’s also unlikely that stress or the effort required in being inverted caused the disruption of direction-specific firing or the poor performance from the novel start location because similar factors were present during the familiar start sessions and rats had to successfully disambiguate these two locations. Finally, it seems unlikely that poor performance reflects a general deficit in generating novel routes as other studies have demonstrated that rats are able to locate a hidden platform from a novel start location in the water maze task, although these rats were started from an upright orientation [10].

Direction-specific firing of HD cells was completely disrupted when the inverted rats were released from the familiar or novel start points. While this finding may not be surprising for when the rats were released from the apparatus center and could not navigate successfully to the escape hole, accounting for accurate performance without an intact HD signal when the rats were released from the two trained entry points requires a deeper understanding of the underlying spatial strategies used by the rats, and raises the question of when is an intact HD signal necessary for navigation. Because release from the familiar entry points did not require the use of a cognitive mapping strategy, the absence of directional firing was apparently not detrimental to their performance. However, when a flexible spatial, cognitive map-like strategy was required when released from the apparatus center, the absence of HD cell firing impaired their ability to chart an accurate trajectory from the novel release point. Even repeated releases from the apparatus center up to five times spaced over one week did not lead to improvement in their performance or in the extent of direction-specific firing. Of course, it’s likely that with repeated training from the center start location, the rats would have learned the correct trajectory, just as they had from the two familiar release points. But with the continued absence of direction-specific firing, it’s also likely that they would have used a habit-like, directional associational strategy, rather than a cognitive mapping strategy, and no direction-specific firing would be observed. Taken together, our results indicate that intact directional firing in HD cells is necessary to support navigation when there is a greater reliance on the use of flexible spatial representations to enable a cognitive mapping strategy. Although we did not monitor HD cell activity during the initial training period of the inverted task, it is unlikely that ‘normal’ directional firing was present then because we have never observed an intact HD signal when the animal is inverted. This observation suggests that the rats can learn a spatial habit without an intact HD signal.

Previous studies have shown that the HD signal originates from neurons that are closely tied to the vestibular system [11,12]. When released from an inverted orientation, the rats may have placed their vestibular labyrinth in such an unfamiliar state that they were unable to process the vestibular signal, and this condition subsequently led to the disruption in the HD signal. Movements from an inverted position would unlikely affect the vestibular semicircular canals, which are primarily sensitive to angular head rotation, but would affect the otolith organs, which are sensitive to linear head acceleration and gravity. Indeed, the otolith organs apparently contribute to the HD signal because the HD signal is disrupted in otolith deficient mutant mice [13]. Further, studies have shown that the otolith signal is less sensitive when a subject’s head is in an inverted position [14,15].

Our findings may account for why astronauts have difficulty with spatial relationships in space, particularly with 3D relationships, and frequently become disoriented [16]. If astronauts also have disrupted HD cell activity when in 0-g, this situation may explain their navigational impairments and their subsequent reliance on other strategies for solving spatial problems - similar to the rats in our study. Our findings also raise the question of what does it mean to be disoriented? Were the rats disoriented when inverted and trying to reach the escape hole? On one level, based on a disrupted directional signal and an inability to formulate an accurate trajectory in the Center sessions, the answer may be affirmative. On the other hand, the rats were able to set a proper course when released from the two familiar locations despite the absence of an intact directional signal, which suggests that at some level they were oriented. This situation indicates there may be a dissociation between one’s perceived orientation and the ability to chart an accurate course, where the former relies on an intact HD signal and the latter relies on the navigational strategy used by the animal.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

HD cells were recorded while rats were inverted and navigated to an escape hole from a familiar or novel location.

Direction-specific firing was disrupted following release from both conditions.

Rats navigated to the escape hole accurately from the familiar release points, but not from the novel entry point.

Accurate navigation involving a flexible representation of space requires a functional HD signal.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jennifer Rilling for help with data collection and Katherine Cart for assistance with data analysis for this project. This work was supported by grants from NIH NS053907, DC009318.

References

- 1.Taube JS. The head direction signal: origins and sensory-motor integration. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:181–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Keefe J, Nadel L. The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moser EI, Moser MB. A metric for space. Hippocampus. 2008;18(12):1142–1156. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valerio S, Clark B, Chan J, Frost CP, Harris MJ, Taube JS. Directional learning, but no spatial mapping by rats performing a navigational task in an inverted orientation. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2010;93:495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calton JL, Taube JS. Degradation of head direction cell activity during inverted locomotion. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2420–2428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3511-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taube JS, Stackman RW, Calton JL, Oman CM. Rat head direction cell responses in zero-gravity parabolic flight. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2887–2997. doi: 10.1152/jn.00887.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skinner DM, Etchegary CM, Ekert-Maret EC, Baker CJ, Harley CW, Evans JH, Martin GM. An analysis of response, direction, and place learning in an open field and T maze. J Exp Psych:Animal Behav Proc. 2003;29:3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton DA, Akers KG, Sutherland RJ. How do room and apparatus cues control navigation in the Morris water task? Evidence for distinct contributions to a movement vector. J Exp Psych: Animal Behav Proc. 2007;33:100–114. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.33.2.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tolman EC. Cognitive maps in rats and men. Psych Rev. 1948;55:189–208. doi: 10.1037/h0061626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eichenbaum H, Stewart C, Morris RGM. Hippocampal Representation in Place Learning. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3531–3542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03531.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stackman RW, Taube JS. Firing properties of head direction cells in the rat anterior thalamic nucleus: dependence on vestibular input. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4349–4358. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04349.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muir GM, Brown JE, Carey JP, Hirvonen TP, Della Santina CC, Minor LB, Taube JS. Disruption of the head direction cell signal after occlusion of the semicircular canals in the freely moving chinchilla. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14521–14533. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3450-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoder RM, Taube JS. Head direction cell activity in mice: robust directional signal depends on intact otolith organs. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1061–1076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1679-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plotnik M, Freeman S, Sohmer H, Elidan J. The effect of head orientation on the vestibular evoked potentials to linear acceleration impulses in rats. Am J Otol. 1999;20:735–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh EG. Perception of linear motion following unilateral labyrinthectomy: variation of threshold according to the orientation of the head. J Physiol. 1960;153:350–357. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1960.sp006538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oman CM. Spatial orientation and navigation in microgravity. In: Mast FW, Jäncke L, editors. Spatial processing in navigation, imagery and perception. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.