Abstract

Aims:

In 2010, the English Department of Health launched a radical new public health strategy, which sees individual factors, such as self-esteem, as the key to improving all aspects of young people’s health. This article compares the strength of association between key adolescent health outcomes and a range of individual and social factors

Methods:

All participants aged 12–15 in the nationally representative 2008 Healthy Foundations survey were included. Six individual factors related to self-esteem, confidence and personal responsibility, and seven social factors related to family, peers, school and local area were investigated. Single-factor and multivariable logistic regression models were used to calculate the association between these factors and seven health outcomes (self-reported general health, physical activity, healthy eating, weight, smoking, alcohol intake, illicit drug use). Odds ratios were adjusted for gender, age and deprivation.

Results:

Individual factors such as self-esteem were associated with general health, physical activity and healthy eating. However, the influence of family, peers, school and local community appear to be equally important for these outcomes and more important for smoking, drug use and healthy weight.

Conclusion:

Self-esteem interventions alone are unlikely to be successful in improving adolescent health, particularly in tackling obesity and reducing substance misuse.

Keywords: adolescent health, behaviour, England, Public Health White Paper

Introduction

The World Health Organization estimates that nearly two-thirds of premature deaths are associated with risk factors predominantly initiated in adolescence1 and has declared young people’s health a global health priority.2 Eighty per cent of smokers start before the age of 21,3 half of lifetime mental illness presents by the age of 144 and up to 79% of obese teenagers will be obese as adults.5

In the UK and elsewhere, adolescent health has been a growing focus of academic and policy interest over the past decade.5–7 In 2007, a United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) report found that British young people had the least healthy lifestyles of 21 countries studied, reflecting high rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, cannabis use, unprotected sex, poor diet, obesity and violent behaviour.8 The report Fair Society, Healthy Lives demonstrated the importance of social determinants of health at all ages, using a life course approach.9

When the UK coalition government was formed in May 2010, the Secretary of State for Health, Andrew Lansley, affirmed its commitment to young people’s health.10 Radical reforms were announced in several relevant policy areas, including public health, well-being, schools, the National Health Service (NHS) and community policy.

The Public Health White Paper11 places a firm focus on improving young people’s health and health behaviours through promoting self-esteem, confidence and personal responsibility (p. 6). At the same time it acknowledges the role of wider social environmental factors in promoting good health, such as social norms (section 1.13), relationship with parents (section 1.22), peer influence and school support (section 3.16).

Evidence suggesting that these policy changes will improve health outcomes for young people is inconsistent. There is strong evidence that connection with family and community is protective against a range of poor health outcomes in adolescents12 and that social determinants of health are important in adolescence.13 However, evidence that promoting self-esteem and personal responsibility will improve young people’s health is sparse. Self-esteem can be defined as ‘how much value people place on themselves’14 and has been extensively studied using tools such as the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale.15 A recent systematic review of such studies found no consistent relationship between higher self-esteem and better health outcomes in adolescence.14 Further, much of the work in this area has been undertaken outside the UK, and it is not clear that findings should be used to guide policy in Britain.

A recent survey of young people’s health behaviour and attitudes, the Healthy Foundations study, provides an opportunity to examine whether these new policy initiatives are likely to influence health and health behaviours in British adolescents.16 This study was funded by the English Department of Health as part of a wider survey into health behaviour and motivation across the life course. We used data from the Healthy Foundations study to compare the strength of the relationship between individual and social factors relevant to the new reforms and health outcomes in early adolescence. We identified self-esteem, personal responsibility and confidence as individual factors, and school, peers, family and community connections as social determinants.

Methods

Sampling

Healthy Foundations study data were obtained from the English Department of Health. The study identified respondents using a random population-based sampling methodology. To enable detailed analysis of deprivation effects, there was over-sampling of the most deprived decile of areas, as measured by the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD).17 Analyses were weighted to be nationally representative. A full description of the sampling and methods can be found in the full report of The Healthy Foundations Research Projects.16

The final sample included 5,380 people aged 12–74 resident in England interviewed between March and June 2008, representing a net response rate of 55%. Of these, 452 were 12–15 years old, who form the subject of these analyses. The 12–15-year-olds completed a confidential 25-minute questionnaire. Computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI) was offered to all respondents as this allowed them to answer the questions in private by reading and responding to the questions on a laptop. Parents or guardians completed a separate questionnaire providing additional information on household demographics.

The questionnaire was designed to capture measures on attitudes, beliefs, behaviour and measures of the social and economic environment within which children live. Questions were drawn from existing surveys and additional new questions were added by the research team. The questionnaire was subjected to two stages of piloting. All fieldwork was conducted by fully trained interviewers from GfK NOP, who worked within the standards of the Interviewer Quality Control Scheme.

Policy factors

Selection of policy factors

We mapped questionnaire items onto policy themes. We identified seven items within the category of individual factors that relate to the policy themes of self-esteem (two items), personal responsibility (two items) and confidence (three items). The two items on self-esteem were combined into a single score for self-esteem, making a total of six individual level factors for analysis. We identified nine items that relate to social factors (either more proximal to the individual, e.g. school, family and peers, or more distal community factors) some of which are also part of the government’s reforms. The two items relating to parental relationships and the two relating to school environment were also combined, making a total of seven social factors for analysis. Table A1 (Appendix) shows the questionnaire items and the categories to which we assigned them.

The questionnaire items from the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (self-esteem) and the Teacher and Classmate Support Scale (school environment) were selected and combined after piloting data demonstrated that they were a valid proxy for the wider scale. Full details of this process have been published previously.16 Respondents were excluded if they did not give a valid response to both questions. Similarly, an average score was created from the two questions about ease of communication with both parents/carers. If the young person was not in contact with one parent/carer, this was scored as 0.5 and averaged with the score for the other parent/carer.

Transformation

Policy factor responses were transformed for analysis as responses differed across the nine questions. Scores were firstly standardised then normalised. In step one, a standardised score from 0 to 1 was created for each variable using the formula: Adjusted score = (score - a) / (b-a), where a = minimum score and b = maximum score. Each question was thereby scored from 0 to 1, where 1 represented the most positive response and 0 the least positive. Second, a normalised score for each variable was created from the standardised score by dividing each value by the standard deviation for that score. The normalised scores were used to explore associations of policy factors with healthy outcomes, adjusting for age, gender and deprivation.

We derived standardised scales for age and IMD using the formula Adjusted score = (score - a) / (b-a). This resulted in scores with the following ranges (Age: 0 = age 12, 1 = age 15; IMD: 0 = most deprived decile, 1 = least deprived decile). Unlike the policy factors, the adjusted scores were not then normalised.

Health outcomes

Data on seven health outcomes were available. For analysis, dichotomous groups were created representing good health / healthy behaviour or the reverse according to standard definitions for smoking, alcohol use or weight, and according to current UK recommendations for physical activity and diet (fruit and vegetable intake). Health outcomes were as follows:

Self-reported general health: respondents were asked: ‘In general, how would you say your health is?’ Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale (‘very good’ to ‘very bad’), which was collapsed to a binary outcome: good health (‘very good, good’) versus poor health (‘very bad, bad, neither good nor bad’).

Physically active: defined as meeting the national recommended levels of physical activity for under 16s (60 minutes physical exercise at least five times per week).

Healthy eating: defined as following UK government recommendations to eat at least five portions of fruit and vegetables a day.

Healthy weight: defined as BMI z score for age < 1 on the UK 1990 growth reference.18 BMI z score was calculated from self-reported height and weight. A z score of 1 is equivalent to the 85th BMI centile for age and gender.

Smoking: defined by a positive response to the question: ‘Do you smoke nowadays?’

Alcohol intake: defined as any alcohol drunk within the last week.

Illicit drug use: defined by a positive response to the question: ‘Have you ever taken any illegal drug?’

Analysis

For analysis, data were weighted to compensate for the various design effects introduced by the survey sample design. We examined potential interactions between age, gender, IMD and policy variables. Significant interactions were found between gender, social participation and weekly drinking. Models that included alcohol were therefore stratified by gender, while all other analyses included both sexes and were adjusted for gender.

Associations between policy variables and health outcomes were first examined in logistic regression models adjusted for age, gender and IMD. Policy factors significant (p < .05) in single-variable models were entered into a multi-variable models for each health outcome. The proportion of variance explained was calculated for each model (using Nagelkerke pseudo R 2). Analyses were undertaken in SPSS, version 18.

Ethics

No ethical approval was needed for this secondary analysis of anonymised, previously published data.

Results

In total, 452 young people (237 females (52%)) participated in the survey. The mean age was 13.5 years (SD = 1.1); 212 (46.9%) participants lived in the most deprived decile of postcodes, with approximately equal representation of all other deciles.

Mean scores for each health outcome by gender are presented in Table A2 (Appendix).

Table 1 presents the adjusted odds ratios for general health, physical activity, healthy eating and healthy weight related to individual and social policy factors. Table 2 presents the same for substance misuse, with alcohol data presented separately by gender.

Table 1.

Adjusted odds ratios for general health, physical activity, healthy eating and healthy weight by policy factor

| Single-factor model (adjusted for gender,

age, IMD) |

Multi-variable model (adjusted for all

significant factors, age, gender, IMD) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| General health | ||||||

| Individual | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 1.51 | 1.17–1.95 | .002 | 1.37 | 1.02–1.84 | .038 |

| Involvement in health | 1.81 | 1.41–2.33 | < .001 | 1.85 | 1.32–2.60 | < .001 |

| What I personally do | 1.32 | 1.03–1.70 | .028 | 1.01 | 0.74–1.38 | .960 |

| Be myself | 1.12 | .390 | ||||

| Achievement | 1.67 | 1.29–2.15 | < .001 | 1.12 | .501 | |

| Confidence | 1.20 | .212 | ||||

| Microsystem | ||||||

| Can talk to parents | 1.10 | .482 | ||||

| Friends care about health | 1.36 | 1.04–1.76 | .023 | 0.79 | .200 | |

| Social participation | 1.39 | 1.06–1.81 | .017 | 1.18 | .306 | |

| Safe neighbourhood | 1.50 | 1.15–1.96 | .003 | 1.40 | 1.02–1.93 | .040 |

| School connectedness | 1.35 | 1.05–1.75 | .022 | 1.34 | 0.94–1.92 | .106 |

| School environment | 1.56 | 1.19–2.03 | .001 | 1.19 | .319 | |

| Age | 1.16 | 0.49–2.77 | .738 | |||

| Gender | 0.91 | 0.46–1.79 | .779 | |||

| IMD | 1.18 | 0.42–3.34 | .755 | |||

| Nagelkerke value | .20 | |||||

| Physically active | ||||||

| Individual | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 1.69 | 1.26–2.26 | < .001 | 1.52 | 1.11–2.07 | .009 |

| Involvement in health | 1.56 | 1.17–2.09 | .002 | 1.44 | 1.06–1.94 | .018 |

| What I personally do | 1.19 | .160 | ||||

| Be myself | 1.36 | 1.06–1.76 | .016 | 1.14 | .322 | |

| Achievement | 0.982 | .877 | ||||

| Confidence | 1.06 | .609 | ||||

| Microsystem | ||||||

| Can talk to parents | 0.97 | .787 | ||||

| Friends care about health | 1.19 | .159 | ||||

| Social participation | 2.07 | 1.53–2.79 | < .001 | 1.94 | 1.42–2.66 | < .001 |

| Safe neighbourhood | 1.06 | .619 | ||||

| School connectedness | 1.18 | .169 | ||||

| School environment | 0.81 | .068 | ||||

| Age | 1.60 | 0.81–3.18 | .176 | |||

| Gender | 0.46 | 0.28–0.76 | .002 | |||

| IMD | 1.17 | 0.54–2.57 | .689 | |||

| Nagelkerke value | 0.22 | |||||

| Healthy eating | ||||||

| Individual | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 1.09 | .389 | ||||

| Involvement in health | 1.31 | 1.06–1.62 | .013 | 1.27 | 1.00–1.62 | .055 |

| What I personally do | 1.08 | .475 | ||||

| Be myself | 0.99 | .940 | ||||

| Achievement | 1.29 | 1.05–1.60 | .017 | 1.13 | 0.88–1.44 | .322 |

| Confidence | 1.29 | 1.05–1.58 | .015 | 1.36 | 1.11–1.68 | .004 |

| Microsystem | ||||||

| Can talk to parents | 1.07 | .528 | ||||

| Friends care about health | 1.24 | 1.00–1.52 | .046 | 1.07 | .572 | |

| Social participation | 1.10 | .349 | ||||

| Safe neighbourhood | 1.08 | .459 | ||||

| School connectedness | 1.11 | .329 | ||||

| School environment | 1.29 | 1.05–1.59 | .018 | 1.25 | 1.00–1.57 | .050 |

| Age | 0.78 | 0.44–1.36 | .376 | |||

| Gender | 0.89 | .589 | ||||

| IMD | 2.34 | 1.20–4.55 | .012 | |||

| Nagelkerke value | 0.11 | |||||

| Healthy weight | ||||||

| Individual | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 1.20 | .108 | ||||

| Involvement in health | 1.12 | .308 | ||||

| What I personally do | 1.05 | .650 | ||||

| Be myself | 1.09 | .451 | ||||

| Achievement | 0.80 (0.60) F | 0.63–1.01 (0.39–0.92) F | .059 (.018) F | |||

| Confidence | 1.08 | .491 | ||||

| Microsystem | ||||||

| Can talk to parents | 1.14 | .249 | ||||

| Friends care about health | 1.05 | .650 | ||||

| Social participation | 1.13 | .264 | ||||

| Safe neighbourhood | 1.33 | 1.05–1.69 | .017 | 1.33 | 1.05–1.69 | .017 |

| School connectedness | 1.09 | .433 | ||||

| School environment | 1.12 | .317 | ||||

| Age | 1.69 | .080 | ||||

| Gender | 1.46 | .101 | ||||

| IMD | 1.39 | .368 | ||||

| Nagelkerke value | 0.04 | |||||

Notes: Odds ratios are presented for the association between 12 policy factors (six individual factors and six microsystem factors) and seven health outcomes.

An odds ratio greater than 1 indicates that the odds of health or healthy behaviour increase with higher self-esteem, school-connectedness, etc.

For demographic factors, an odds ratio greater than 1 indicates that the odds of health or healthy behaviour increase with age and higher socio-economic status and are higher for females compared to males.

Two models are presented for each health outcome. The left-hand column shows the adjusted odds ratios for each policy factor score, adjusted for age, gender and IMD. These were named as single-factor models. The right-hand column then shows a multi-variable model, which includes all policy factors significant (p < .05) at the partially adjusted stage.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios for substance misuse by policy factor

| Single-factor model (adjusted for gender,

age, IMD) |

Multi-variable model (adjusted for all

significant factors, age, gender, IMD) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Non-smoker | ||||||

| Individual | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 1.11 | .581 | ||||

| Involvement in health | 1.30 | .132 | ||||

| What I personally do | 0.90 | .598 | ||||

| Be myself | 1.12 | .573 | ||||

| Achievement | 1.49 | 1.06–2.08 | .022 | 1.17 | .497 | |

| Confidence | 0.92 | .673 | ||||

| Microsystem | ||||||

| Can talk to parents | 1.50 | 1.07–2.11 | .020 | 1.63 | 1.07–2.48 | .024 |

| No smokers at home | 6.65 | 2.71–16.31 | < .001 | 14.9 | 4.5–49.4 | < .001 |

| Friends care about health | 1.33 | .121 | ||||

| Social participation | 1.26 | .221 | ||||

| Safe neighbourhood | 1.71 | 1.18–2.48 | .005 | 1.70 | 1.06–2.70 | .027 |

| School connectedness | 1.26 | .217 | ||||

| School environment | 2.25 | 1.53–3.30 | < .001 | 2.26 | 1.35–3.78 | .002 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.01–0.24 | < .001 | |||

| Gender | 1.4 | .52 | ||||

| IMD | 0.32 | .162 | ||||

| Nagelkerke value | 0.39 | |||||

| Male non-drinker | ||||||

| Individual | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 1.02 | .935 | ||||

| Involvement in health | 0.44 | 0.24–0.81 | .009 | 0.44 | 0.24–0.81 | .009 |

| What I personally do | 0.66 | .126 | ||||

| Be myself | 1.27 | .252 | ||||

| Achievement | 0.78 | .267 | ||||

| Confidence | 0.83 | .413 | ||||

| Microsystem | ||||||

| Can talk to parents | 1.39 | .126 | ||||

| No heavy drinkers at home | 1.69 | .345 | ||||

| Friends care about health | 1.19 | .453 | ||||

| Social participation | 1.46 | .067 | ||||

| Safe neighbourhood | 0.75 | .321 | ||||

| School connectedness | 1.48 | 0.99–2.22 | .053 | |||

| School environment | 1.23 | .380 | ||||

| Age | 0.04 | 0.01–0.20 | < .001 | |||

| IMD | 1.20 | .804 | ||||

| Nagelkerke value | 0.23 | |||||

| Female non-drinker | ||||||

| Individual | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 1.24 | .298 | ||||

| Involvement in health | 1.11 | .609 | ||||

| What I personally do | 1.05 | .833 | ||||

| Be myself | 1.33 | .189 | ||||

| Achievement | 0.67 | .172 | ||||

| Confidence | 0.96 | .865 | ||||

| Microsystem | ||||||

| Can talk to parents | 1.22 | .329 | ||||

| No heavy drinkers at home | 2.71 | .13 | ||||

| Friends care about health | 0.96 | .863 | ||||

| Social participation | 0.48 | 0.28–0.81 | .007 | 0.48 | 0.28–0.81 | .007 |

| Safe neighbourhood | 0.72 | .212 | ||||

| School connectedness | 1.31 | .223 | ||||

| School environment | 1.37 | .148 | ||||

| Age | 0.08 | 0.02–0.35 | .001 | |||

| IMD | 0.62 | .509 | ||||

| Nagelkerke value | 0.18 | |||||

| Never taken drugs | ||||||

| Individual | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 1.43 | .063 | ||||

| Involvement in health | 1.33 | .14 | ||||

| What I personally do | 0.94 | .769 | ||||

| Be myself | 0.80 | .364 | ||||

| Achievement | 1.29 | .177 | ||||

| Confidence | 0.83 | .397 | ||||

| Microsystem | ||||||

| Can talk to parents | 0.82 | .428 | ||||

| No drugs used at home | 146 | 3.8–5670 | .008 | 395 | 9–16918 | .002 |

| Friends care about health | 2.15 | 1.49–3.11 | < .001 | 2.59 | 1.69–3.96 | < .001 |

| Social participation | 1.39 | 0.94–2.05 | .095 | |||

| Safe neighbourhood | 1.39 | .106 | ||||

| School connectedness | 0.83 | .44 | ||||

| School environment | 1.52 | 1.01–2.30 | .047 | 1.31 | 0.82–2.07 | .256 |

| Age | 0.42 | .226 | ||||

| Gender | 1.98 | .195 | ||||

| IMD | 6.88 | 1.34–35.4 | .021 | |||

| Nagelkerke value | 0.31 | |||||

Notes: Odds ratios are presented for the association between 13 policy factors (six individual factors and seven microsystem factors) and seven health outcomes.

Interactions were detected between social participation, gender and weekly drinking. Male and female data on weekly drinking are therefore presented separately. Data for all other outcomes are aggregated to maximise statistical power.

Two models are presented for each health outcome. The left-hand column shows the adjusted odds ratios for each policy factor score, adjusted for age, gender and IMD. These were named as single-factor models. The right-hand column then shows a multi-variable model, which includes all policy factors significant (p < .05) at the partially adjusted stage.

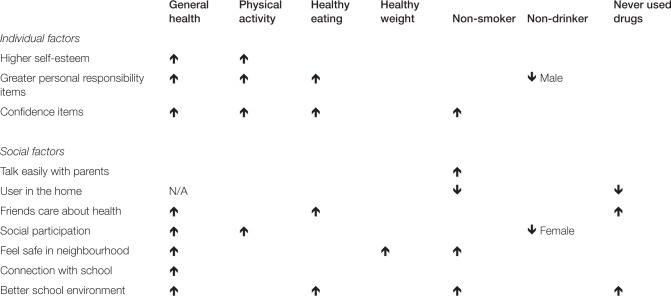

Single-factor models

A summary of significant associations in the single-factor models is shown in Figure 1. Good general health was associated with higher scores for the majority of individual and social factors. Individual factors were linked to physical activity and healthy eating but not consistently linked to healthy weight and substance misuse. Positive social factors were associated with better outcomes in all areas except alcohol consumption.

Figure 1.

Associations between individual and social factors and health outcomes in English adolescents

Notes: Arrows indicate a significant association in single-factor models, adjusting for age, gender and deprivation. For example, higher self-esteem is significantly associated with better general health. The presence of a smoker at home is associated with a lower chance of being a non-smoker.

Multi-variable models

In the multi-variable model, better general health was associated with the individual factors of self-esteem, involvement in health and living in a safe neighbourhood. Physical activity was similarly associated with self-esteem and involvement in health, but it was associated with social participation in terms of social factors. Healthy eating was only associated with the individual factor confidence, with a trend for an association with school environment. Being a healthy weight was not associated with any physical factors, and was only associated with safe neighbourhood in terms of social factors.

Being a non-smoker was associated only with social factors, including parental smoking, ability to talk with parents, living in a safe neighbourhood and school environment. Being a non-drinker was associated with involvement in health for males, but with social participation for females. Drug use was associated with drug use at home and friends being concerned about health.

Discussion

Main findings of this study

These data suggest that the strong focus on self-esteem and personal agency seen in current government policy is likely to influence a subset of adolescent health outcomes only. We found that self-esteem, confidence and personal responsibility for health were associated with good general health and with health-promoting behaviours such as healthy eating and physical activity. However, in our data set, these individual factors were not linked with protection against key health risk behaviours such as smoking, drinking or drug use.

In contrast, we found that social factors related to home, peers, school and neighbourhood were strongly associated with substance use as well as other health outcomes. The strongest correlate of smoking was the presence of a smoker at home, followed by the school environment, perceived safety of their area and difficulty talking to parents. Lower rates of drug use were associated with the absence of a drug user in the household, health-conscious friends, school environment and greater deprivation. We found that few of the factors measured influenced alcohol use, although greater personal responsibility was associated with more frequent alcohol use in boys and higher social participation was associated with more frequent alcohol use in girls. Greater social participation and feeling safe within a neighbourhood as well as a positive school environment were associated with a wide range of positive health outcomes.

What is already known on this topic?

Previous studies have shown that liking school is a protective factor against risky sexual behaviour and substance misuse.19–23 Since the Education Bill was passed in November 2011, there has been debate about whether reduced central regulation will have adverse consequences for children’s health.24 Our data illustrate the importance of the school environment for a range of health indicators and suggest that the health impact of school reforms must be carefully monitored. These data also reinforce the important role played by clubs and organisations in keeping young people active, highlighting the risks of policies under which 20% of youth services are predicted to close within the next year.25

Volunteering and community engagement are known to have a wide range of health benefits.26,27 Wilson28 suggests that this may be particularly important in adolescence, reviewing extensive evidence that alienation and disengagement lie at the heart of much risky behaviour in this age group. Interventions aim to promote the belief that ‘I’m a valued member of my school and community’ and have been effective in improving outcomes from increased school attainment to reduced teenage pregnancy and violent behaviour.29,30 Frequency of participation in clubs and organisations does not reflect all aspects of community engagement but clearly has significant health benefits, particularly in providing opportunities for sports and other physical exercise. Similarly, young people are the most common victims of street crime. Ensuring that they feel safe in their local area must be a priority in any efforts to promote community engagement.

What this study adds

Our data are recent, representative of the English population and show clearly how factors related to the proposed policies are associated with key public health indicators.

For policy purposes, the main strengths of the study were the population (a contemporary, nationally representative, random sample drawn from households rather than schools) and the wide scope of the questionnaire. Data collection across many domains allowed associations to be directly compared and interactions analysed.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown an association between high self-esteem and some aspects of health, particularly lower rates of bulimia and increased happiness, but no consistent link between high self-esteem and reduced rates of substance misuse.14,31 In contrast, we found that social factors are strongly linked to the majority of health outcomes.

One area that would benefit from further research is influences on alcohol intake. Our data show that girls who attended a club regularly and boys who felt involved with their health were more likely to report drinking alcohol within the last week. However, around half of those drinkers were aged 15, for whom the Chief Medical Officer recommends that some alcohol intake is safe.32 Interestingly, sub-group analysis of our data showed that among those who had drunk alcohol within the last week, those with high social participation drank less than those with low social participation (mean 2.0 vs 11.3 units, p < .01). Previous research has shown that membership of a team or youth club can be protective against frequent or problem drinking,33,34 although other authors have found a link between higher social self-efficacy and problematic drinking among adolescents.35 Clearly, further exploration is needed before these findings should influence policy.

Limitations of the study

In common with all cross-sectional surveys, the data allow inferences to be drawn about association but not causation. The breadth of the study also meant that it was not possible to investigate each factor in depth. For example, previous studies have used longer self-esteem scales to investigate different domains of self-esteem, whereas our study uses only two questionnaire items to represent global self-esteem.

This survey has a smaller sample size than some studies and may therefore lack sufficient power to detect weak associations. In many cases, these weak associations may be of academic interest but less relevant for national policy decisions. However, the sample size means that extensive sub-group analysis is not possible.

Conclusion

A focus on self-esteem and personal agency, prominent in the Public Health White Paper, is partially supported by our findings on general health, physical activity and healthy eating. However, the influence of family, peers, school and local community appear to be equally important for these outcomes and more important for smoking, drug use and healthy weight.

Self-esteem interventions alone are unlikely to be successful in improving adolescent health, particularly in tackling obesity and reducing substance misuse. A successful public health strategy must take a holistic approach to tackling determinants of young people’s health.

Footnotes

Funding: No specific funding was associated with this article.

Conflicts of Interest: We declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Dougal S Hargreaves, General and Adolescent Paediatrics Unit, UCL Institute of Child Health, 30 Guilford Street, London. WC1N 3EH, UK.

Dominic McVey, Word of Mouth Research, Hampton, Middlesex, UK.

Agnes Nairn, EMLYON Business School, Paris, France.

Russell M Viner, UCL Institute of Child Health, London, UK.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Young People: Health Risks and Solutions. WHO, 2011. Available online at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs345/en/index.html (Last accessed December 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health. You’re Welcome: Quality Criteria for Young People Friendly Services. London: Department of Health, 2011. Available online at http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_126813 (Last accessed December 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 3. US Department of Health and Human Services. Reducing the Health Consequences of Smoking: 25 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 2005; 62: 593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Donaldson L. Under their Skins: Tackling the Health of the Teenage Nation. Chief Medical Officer’s Annual Report 2007. London: Department of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organisation. Adolescent Friendly Health Services: An Agenda for Change. Geneva: WHO, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patton GC, Viner RM, Linh LC, Ameratunga S, Fatusi AO, Ferguson BJ, et al. Mapping a global agenda for adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health 2010; 47: 427–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. UNICEF. Child Poverty in Perspective: An Overview of Child Well-Being in Rich Countries: Innocenti Report Card 7. New York: UNICEF, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marmot M. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post 2010. London: The Marmot Review, 2010. Available online at http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/ (Last accessed December 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lansley A. A new approach to public health. Secretary of State for Health’s speech to the UK Faculty of Public Health Conference, 2010. Available online at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/MediaCentre/Speeches/DH_117280 (Last accessed December 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 11. Department of Health. Healthy Lives, Healthy People: Our Strategy for Public Health in England. London: Department of Health, 2010. Available online at http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_121941 (Last accessed December 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 12. Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association 1997; 278: 823–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, Fatusi A, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 2012; 379: 1641–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, Vohs KD. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest 2003; 4: 1–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Child. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williams B, McVey D, MacGregor E, Davies L. The Healthy Foundations Lifestage Segmentation; Research Report No. 1: Creating the Segmentation Using a Quantitative Survey of the General Population of England. London: Department of Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Noble M, McLennan D, Wilkinson K, Whitworth A, Barnes H, Dibben C. The English Indices of Deprivation 2007. London: Communities and Local Government, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA. Body mass index reference curves for the UK, 1990. Archives of Disease in Childhood 1995; 73(1): 25–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Currie C, Gabhainn SN, Godeau E, Roberts C, Smith R, Currie D, et al. Inequalities in Young People’s Health: Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children: International Report from the 2005/2006 Survey. Copenhagen: WHO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dias SF, Matos MG, Goncalves AC. Preventing HIV transmission in adolescents: An analysis of the Portuguese data from the Health Behaviour School-Aged Children study and focus groups. European Journal of Public Health 2005; 15: 300–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nutbeam D, Smith C, Moore L, Bauman A. Warning! Schools can damage your health: Alienation from school and its impact on health behaviour. Journal of Paediatric Child Health 1993; 29 (Suppl 1): S25–S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rasmussen M, Damsgaard MT, Holstein BE, Poulsen LH, Due P. School connectedness and daily smoking among boys and girls: The influence of parental smoking norms. European Journal of Public Health 2005; 15: 607–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maes L, Lievens J. Can the school make a difference? A multilevel analysis of adolescent risk and health behaviour. Social Science & Medicine 2003; 56: 517–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. The Daily Telegraph. Jamie Oliver attacks Michael Gove over school meals. The Daily Telegraph, 25 November 2011. Available online at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/8914862/ Jamie-Oliver-attacks-Michael-Gove-over-school-meals.html (Last accessed December 2012)

- 25. BBC News. Parliament rally over cuts to youth services. BBC News, 25 October 2011. Available online at http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-15443138 (Last accessed December 2012)

- 26. Mbema C. Policy Summary: Volunteering. The Lancet UK Policy Matters, 2011. Available online at http://ukpolicymatters.thelancet.com/?p=1529 (Last accessed December 2012)

- 27. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Community Engagement to Improve Health. London: NICE, 2008. Available online at http://guidance.nice.org.uk/PH9/Guidance/pdf/English (Last accessed December 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wilson TD. Redirect: The Surprising New }Science of Psychological Change. London: Penguin, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Allen JP, Philliber S. Who benefits most from a broadly targeted prevention program? Differential efficacy across populations in the teen outreach program. Journal of Community Psychology 2001; 29: 637–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. O’Donnell L, Stueve A, O’Donnell C, Duran R, San DA, Wilson RF, et al. Long-term reductions in sexual initiation and sexual activity among urban middle schoolers in the reach for health service learning program. Journal of Adolesc Health 2002; 31(1): 93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. West P, Sweeting H. ‘Lost souls’ and ‘rebels’: A challenge to the assumption that low self-esteem and unhealthy lifestyles are related. Health Education 1997; 5: 161–7 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Department of Health. Guidance on the Consumption of Alcohol by Children and Young People: A Report by the Chief Medical Officer. London: Department of Health, 2009. Available online at http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_110258 (Last accessed December 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 33. Costa FM, Jessor R, Turbin MS. Transition into adolescent problem drinking: The role of psychosocial risk and protective factors. Journal Stud Alcohol 1999; 60: 480–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bellis MA, Hughes K, Morleo M, Tocque K, Hughes S, Allen T, et al. Predictors of risky alcohol consumption in schoolchildren and their implications for preventing alcohol-related harm. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention and Policy 2007; 2: 15 DOI: 10.1186/1747-597X-2-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McKay MT, Percy A, Goudie AJ, Sumnall HR, Cole JC. The Temporal Focus Scale: Factor structure and association with alcohol use in a sample of Northern Irish school children. Journal of Adolescence 2012; 35: 1361–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]