Abstract

This case report describes a case of ulcerative colitis the onset of which occurred after the use of isotretinoin for acne treatment. Our patient, a healthy male young adult, after several months of isotretinoin use, developed gastrointestinal disorders and after thorough medical workup was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis. The literature regarding a possible correlation between isotretinoin use and ulcerative colitis is scarce. Nevertheless, recent epidemiological studies have shed more light on this possible association.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, Isotretinoin, Acne, Inflammatory bowel disease, Heroin addiction

Core tip: Case reports suggest that isotretinoin administration may trigger inflammatory bowel diseases. This hypothesis has raised great scientific interest and numerous propositions addressing the pathophysiology of this potent association have been made. However, demographic data do not support a correlation between isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease. The current case describes a patient who developed ulcerative colitis while on isotretinoin administration. We hope that this case report may contribute to future epidemiological studies with scope to clarify the association between isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel diseases and more specifically ulcerative colitis.

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease affecting mostly young adults[1]. Acne is a skin disease that occurs commonly in adolescents and young adults[2]. Isotretinoin is a synthetic analogue of vitamin A and it is approved as treatment of severe acne that is resistant to standard therapy[3]. It has been prescribed to many patients worldwide since its introduction in 1982. Isotretinoin use has some known and well described severe adverse effects. Therefore the onset of ulcerative colitis after isotretinoin use had been reported only in case reports and therefore the risk had not been assessed[4]. Although the association of isotretinoin with ulcerative colitis has probably been answered in recent large epidemiological studies[1]. The objective of this case report is to demonstrate a case of a young male who was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis after being treated with isotretinoin for eight months and to review current literature for this association.

CASE REPORT

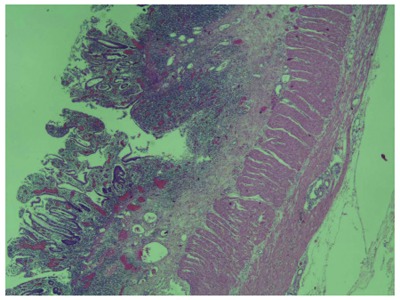

A 29-year-old male with past medical history of heroin addiction referred to our clinic for surgical treatment of severe ulcerative colitis resistant to conservative treatment and anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. Our patient was diagnosed with acne vulgares in 2007 and was treated with isotretinoin 20 mg two times daily with good results. After eight months of treatment he developed bloody diarrheas accompanied by abdominal pain. No fever or skin rashes or weight loss has been reported and had no medical or family history of gastrointestinal diseases. He was referred to a gastroenterological clinic. He admitted being addicted to heroin since 2004 but had stopped heroin use about 3 mo before this incident. Differential diagnosis on this case proposed that infectious reasons of gastroenteritis and diseases related to drug abuse should be overruled first. In that direction, stool cultures were negative for bacteria and parasites as were examinations for sexually transmitted diseases, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus infection and endocarditis. Abdominal X-ray was done with no specific findings. Finally colonoscopy was performed and biopsies were obtained. The endoscopic image resembled that of ulcerative colitis. The histological examination defined, from the typical histopathological findings, the diagnosis of UC (Figure 1). Isotretinoin was discontinued and he started treatment with mesalazine for six months with no significant improvement. Therefore was treated with corticosteroids at an outpatient gastroenterological clinic for several months with good clinical results. Mesalazine was used as maintenance treatment. Mild flares were reported rarely in the years that followed.

Figure 1.

Biopsy from colonoscopy which revealed mucosal inflammation, compatible with ulcerative colitis.

Soon after the first severe colitis episode he relapsed in his heroin addiction. Fortunately, about a year ago, he entered an anti-addiction treatment program and was treated with methadone.

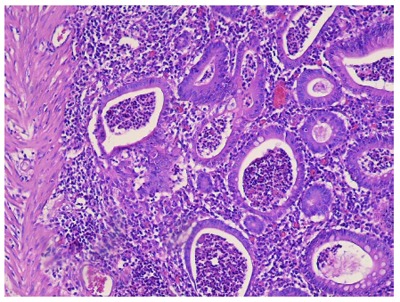

However five months ago there was a severe relapse of the disease, as depicted by Truelove and Witts severity index. Laboratory findings are summarized in Table 1. The patient had more than 6 bloody diarrheas per day and reported a loss of 15 kg in the precedent two months. The patient required hospitalization for two weeks in a gastroenterological clinic. Stool cultures were negative and he was treated with corticosteroids, antibiotics and parenteral nutrition due to severe malnourishment. In addition, he was treated for his heroin-addiction. There was no clinical improvement and thus rescue therapy with anti-TNF started. The colitis did not respond to infliximab and therefore surgical treatment was proposed. He underwent subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy and mucous fistula of the remaining rectal stump, due to the risk of a vulnerable and unsafe reconstruction. The histopathological findings of the surgical specimens once more confirmed the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Laboratory findings

| Test | Result | Normal lab values |

| WBC | 21.300 per mcL | 4-9 × 1000 per mcL |

| NEU | 95% | 43%-75% |

| LYM | 1% | 11%-49% |

| CRP | 5.9 mg/dL | 0.0-0.5 mg/dL |

| RBC | 3.17 × 106/UL | 3.8-5.3 × 106/UL |

| Hb | 9.6 g/dL | 13.5-17.0 g/dL |

| ESR | 47 mm/h | M < 50 y.o: 0-15 mm/h |

| Htc | 28% | 40.0%-51.0% |

| Platelets | 316 × 103/uL | 120-380 × 103/uL |

| Alb | 1.7 g/dL | 3.5-5.5 g/dL |

| Total protein | 4.6 g/dL | 6.0-8.0 g/dL |

WBC: White blood cells; NEU: Neutrophils; LYM: Lymphocyte; CRP: C-reactive protein; RBC: Red blood cells; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Figure 2.

Histopathological image from the excised colon, typical of ulcerative colitis. This image demonstrates marked lymphocytic infiltration (blue/purple) of the intestinal mucosa and architectural distortion of the crypts (right side of the image). The inflammation is shallow and affects only the mucosa sparing the muscularis mucosal (left side).

During hospitalization he was also assessed by psychiatrists for his addiction. He was discharged ten days post-surgery in a significantly improved clinical status. A second restorative operation will be performed later.

DISCUSSION

This case report presented a probable adverse effect of isotretinoin that has been reported rarely by scientists. To the best of our knowledge this is the first case report of ulcerative colitis (UC) related to isotretinoin treatment in Greece. Not many cases of UC after isotretinoin exposure had been reported since its introduction for clinical use in 1982[5]. A possible mechanism is considered to be the prevention of epithelial cell growth and the activation of T-cells. Another theory is that the T-cells that are activated by isotretinoin, express the α4β7 and CCR9 receptors which are crucial to the process of the inflammation in the gastrointestinal system[6]. Several lawsuits have been filled implying correlation between isotretinoin and UC. The fact is that it is not possible to associate adequately isotretinoin isotretinoin and UC based on case reports or small case series. Moreover case reports cannot quantify the risk of UC after isotretinoin treatment[5]. The results from observational studies that followed were still confounding for a positive association. Despite all these, recent epidemiological studies and a meta-analysis suggests that isotretinoin does not increase the risk of UC[7].

Table 2 shows the pooled RR for UC from several large epidemiological studies. Bernstein et al[2] found no association between UC and isotretinoin. But Crockett et al[8] reported a strong association between them. They also demonstrated that the risk was elevated not only if the dose was increased (OR per 20 mg dose increase: 1.50 95%CI: 1.08-2.09) but also if the therapy with isotretinoin was longer than two months (OR = 5.63, 95%CI: 2.10-15.03). However the recent meta-analysis by Etminan et al[7] suggested that there is no correlation between UC and isotretinoin. The pooled RR from their study after the proper adjustment was 1.61 95%CI: 0.88-2.95. Another issue is that the onset of UC is about the same age as acne and UC has also extra-intestinal skin manifestations that can be misinterpreted as acne[9]. Alhusayen et al[1] observed that in the subgroup of 12-19 years old; there was a weak but significant association of inflammatory bowel disease and isotretinoin (RR = 1.39; 95%CI: 1.03-1.87). They did not report a separate rate ratio for UC in this subgroup. However their prime outcome was that inflammatory bowel disease was not related with isotretinoin. Moreover the studies that demonstrated a positive correlation between isotretinoin and UC did not address the possibility of previous topical treatment of acne. The main reason was that prior studies have shown that there is no association between UC and topical treatment of acne[10]. Alhusayen et al[1] stated that the risk of inflammatory bowel disease after topical acne medication was similar to the risk of isotretinoin. It is still unknown if acne itself is related with inflammatory bowel disease or other inflammatory diseases. Bernstein et al[2] concluded also that there is a smaller possibility for patients with known history of inflammatory bowel disease to use isotretinoin for acne treatment than patients from the general population. In addition there is no association from the literature between UC and heroin addiction. Our finding is similar to Papageorgiou et al[9] because their patient developed also UC after prolonged therapy with isotretinoin taken twice a day. It is worth of noting that in the majority of previous cases, ulcerative colitis’ symptoms developed shortly after the cessation of isotretinoin therapy whereas there are only few cases[11,12], as the present one, addressing to patients who developed symptoms of UC while they were on isotretinoin treatment.

Table 2.

Association between isotretinoin and ulcerative colitis in case control studies

| Ref. | Population | UC [RR (95%CI)] |

| Bernstein et al[2] | Residents of Manitoba Canada | 1.16 (0.56-2.20) |

| Crockett et al[8] | US health claims database | 4.36 (1.97-9.66) |

| Etminan et al[7] | Women using oral contraceptives | 1.10 (0.44-2.70) |

| Alhusayen et al[1] | British Columbia residents | 1.31 (0.96-1.80) |

UC: Ulcerative colitis.

In conclusion recent data from the literature suggest that the risk for UC does not increase with isotretinoin treatment. However, in clinical practice there are significant questions that remain unanswered, such as the risks vs the benefits resulting from isotretinoin therapy applied to individuals with positive inflammatory bowel disease family history.

What remains to be investigated further, is the role of isotretinoin as a causative factor in ulcerative colitis or inflammatory bowel disease in general.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

Bloody diarrheas accompanied by abdominal pain without fever or skin rashes or weight loss in a patient with personal history of heroin abuse.

Clinical diagnosis

Multiple bloody diarrheas per day accompanied by constant abdominal pain that spread in every abdominal region.

Differential diagnosis

Infectious causes of gastroenteritis, diseases related to drug abuse and inflammatory bowel diseases should be considered.

Laboratory diagnosis

Stool cultures and examinations for sexually transmitted diseases, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus infection and endocarditis were negative, therefore colonoscopy was performed and biopsies were obtained.

Imaging diagnosis

Abdominal X-ray, endoscopy.

Pathological diagnosis

From the endoscopic biopsy the histological findings set the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis (UC).

Treatment

The treatments that the patient underwent were firstly corticosteroids that showed good clinical results with mesalazine as maintenance treatment, thus after a severe relapse of the disease the patient was treated with corticosteroids, antibiotics and parenteral nutrition with no clinical improvement and rescue therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) factors (infliximab) was used, finally he underwent surgical treatment (subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy and mucous fistula of the remaining rectal stump).

Related reports

UC is a bowel disease that in not quite sure what are its triggering factors. Though many factors are assumed to be associated to the onset of the disease. Some factors are very well studied but others need more research in order to be blamed. The use of isotretinoin, a widely used treatment for acne is associated to UC even though the case reports describing the linkage are few.

Term explanation

Isotretinoin is a medication related to vitamin A used primarily for severe cystic acne and acne that has not responded to other treatments. Anti-TNF therapy (anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy) is a new class of drugs that are approved in treating moderate-to-severe UC. The most common drug used is infliximab, that is a monoclonal antibody that binds to TNF.

Experiences and lessons

UC is a disease that is maybe associated and triggered by more drugs and factors than people already know so in the differential diagnosis of bloody diarrheas in any young patient, should always be the inflammatory bowel diseases.

Peer review

This case report is interesting and well written.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Bresci G, Kirshtein B, Sipos F S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Alhusayen RO, Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Morrow RL, Shear NH, Dormuth CR. Isotretinoin use and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:907–912. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein CN, Nugent Z, Longobardi T, Blanchard JF. Isotretinoin is not associated with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2774–2778. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Passier JL, Srivastava N, van Puijenbroek EP. Isotretinoin-induced inflammatory bowel disease. Neth J Med. 2006;64:52–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergstrom KG. Isotretinoin and inflammatory bowel disease. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:278–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Popescu CM, Bigby M. The weight of evidence on the association of isotretinoin use and the development of inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:221–222. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mora JR. Homing imprinting and immunomodulation in the gut: role of dendritic cells and retinoids. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:275–289. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etminan M, Bird ST, Delaney JA, Bressler B, Brophy JM. Isotretinoin and risk for inflammatory bowel disease: a nested case-control study and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:216–220. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crockett SD, Porter CQ, Martin CF, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD. Isotretinoin use and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1986–1993. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papageorgiou NP, Altman A, Shoenfeld Y. Inflammatory bowel disease: adverse effect of isotretinoin. Isr Med Assoc J. 2009;11:505–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilat T, Hacohen D, Lilos P, Langman MJ. Childhood factors in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. An international cooperative study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;22:1009–1024. doi: 10.3109/00365528708991950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin P, Manley PN, Depew WT, Blakeman JM. Isotretinoin-associated proctosigmoiditis. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:606–609. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90925-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brodin MB. Inflammatory bowel disease and isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:843. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)80535-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]