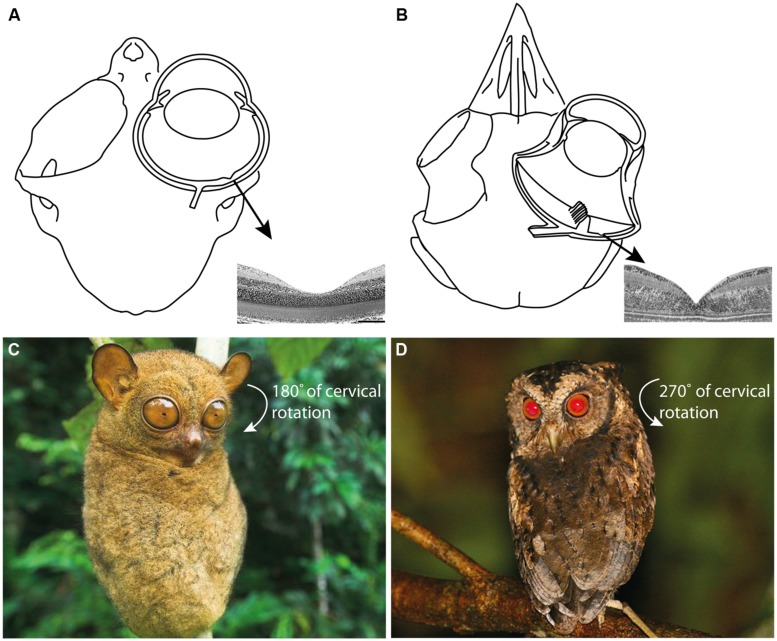

FIGURE 3.

(A) The skull and eye of Tarsius bancanus (modified from Castenholz, 1984; Ross, 2004) together with the fovea of T. spectrum (modified from Hendrickson et al., 2000). (B) The skull, eye, and fovea of a composite strigiform (modified from Fite, 1973; Menegaz and Kirk, 2009). Because ocular mobility is constrained by the hyperenlarged eyes of tarsiers and scops owls, an extraordinary degree of cervical rotation is necessary to enable rapid prey localization and fixation. (C) The increased cervical mobility of tarsiers allows them to rotate their head 180° in azimuth (Castenholz, 1984; photograph of T. bancanus by Nick Garbutt, reproduced with permission). (D) Owls can rotate their head 270° in azimuth (Harmening and Wagner, 2011; photograph of O. lempiji by Paul B. Jones, reproduced with permission). Extreme head rotation is thought to enhance the sit-and-wait ambush mode of predation common to tarsiers and scops owls (Niemitz, 1985).