Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the association of other-than-common benign copy number variants with specific fetal abnormalities detected by ultrasonogram.

Methods

Fetuses with structural anomalies were compared to fetuses without detected abnormalities for the frequency of other-than-common benign copy number variants. This is a secondary analysis from the previously published National Institute of Child Health and Human Development microarray trial. Ultrasound reports were reviewed and details of structural anomalies were entered into a nonhierarchical web-based database. The frequency of other-than-common benign copy number variants (ie, either pathogenic or variants of uncertain significance) not detected by karyotype was calculated for each anomaly in isolation and in the presence of other anomalies and compared to the frequency in fetuses without detected abnormalities.

Results

Of 1,082 fetuses with anomalies detected on ultrasound, 752 had a normal karyotype. Other-than-common benign copy number variants were present in 61 (8.1%) of these euploid fetuses. Fetuses with anomalies in more than one system had a 13.0% frequency of other-than-common benign copy number variants, which was significantly higher (p<0.001) than the frequency (3.6%) in fetuses without anomalies (n = 1966). Specific organ systems in which isolated anomalies were nominally significantly associated with other-than-common benign copy number variants were the renal (p= 0.036) and cardiac systems (p=0.012) but did not meet the adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Conclusions

When a fetal anomaly is detected on ultrasonogram, chromosomal microarray offers additional information over karyotype, the degree of which depends on the organ system involved.

INTRODUCTION

Identification of aneuploidy or other major chromosomal structural anomalies by G banded karyotype has been the standard approach to the prenatal genetic evaluation of fetal structural anomalies. Recently, however, more advanced genomic techniques have been developed that are capable of identifying clinically important chromosomal alterations beneath the resolution of metaphase banded chromosomes. A recent NICHD prospective, blinded study in which chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) was compared to standard karyotype demonstrated that CMA identified clinically relevant copy number variants in 6.0% of anomalous fetuses with a normal karyotype (1). Similarly, a recent systematic review by Hillman et al. showed that in the presence of an abnormal fetal ultrasound, relevant microarray findings other than aneuploidy occurred in 10% (95% CI 8–13%) of cases (2).

The relative effect of CMA for anomalies of specific fetal systems remains uncertain (3). Such information is important as it would allow improved counseling and subsequent decision-making. In this study, we aimed to determine the association of copy number variants with single and multiple ultrasonographically detected anomalies of specific fetal organ systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

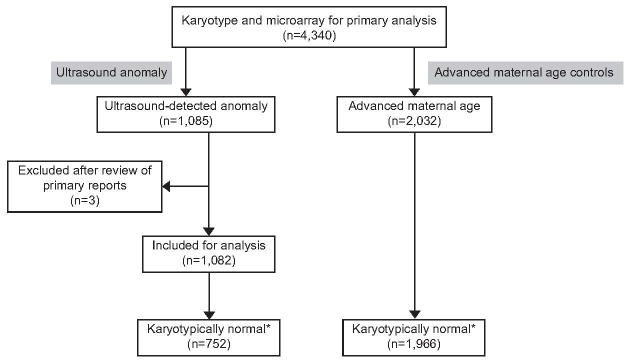

This was a planned secondary analysis of the multicenter NICHD microarray trial which enrolled women at 29 centers(1). IRB approval had been obtained from all sites, the data coordinating center and the participating laboratories. In the primary study, 4,406 women had either chorionic villous sampling or amniocentesis and 4,340 women had both karyotype and CMA results available. Further information regarding the microarray laboratory procedures, confirmation, classification and reporting of array results has previously been described(1). The indications for the procedures included advanced maternal age, positive aneuploidy screening results, structural anomalies detected on ultrasound, a previous child with or other family history of either a genetic or congenital disorder. In the present analysis, the rate of copy number variants for fetuses identified as having an ultrasound-detected abnormality and a normal karyotype was determined and compared to karyotypically normal fetuses without ultrasonographically detected anomalies whose only indication for prenatal diagnosis was advanced maternal age (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study population

* includes all other than common benign copy number variants; U/S = ultrasound; AMA controls = advanced maternal age

For this analysis, all ultrasound reports in which structural anomalies of the fetus were the indication for invasive testing were reviewed centrally by study personnel and data regarding the anomalies were abstracted. In twenty cases, the original ultrasound reports were not available and the anomalies were ascertained using information obtained at the time of the invasive procedure and entered into the primary study datasheet by local investigators. Three of the 1,085 originally coded ultrasound anomaly cases did not meet criteria for classification as an anomaly and were excluded. All details were entered into a non-hierarchical web-based database using the Cartagenia BENCH software which allowed the coding of 19 different anatomical and non-structural categories based on the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO). Fetal growth restriction was classified into 3 subcategories based on an estimated fetal weight being less than the 10th, the 5th, or the 3rd centile for gestational age. Amniotic fluid was classified as oligohydramnios if the maximum vertical pocket was <2cm and polyhydramnios if the maximum vertical pocket was >2 standard deviations (SD) above the mean for gestational age. If specific amniotic fluid measurements were not recorded on the ultrasound report, the qualitative assessment of volume was accepted. Full details of the categories and the subcategories are available as Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx.

Fetuses with multiple anomalies were classified according to each system for which an abnormality was present. Minor soft markers used for aneuploidy screening, such as isolated choroid plexus cysts, mild hydronephrosis (AP diameter between 5–10mm), nuchal translucency <3.5mm or echogenic cardiac foci, were not included in this analysis. A nuchal translucency of ≥3.5mm or a nuchal fold of >6m, or a cystic hygroma were included as ultrasound detected anomalies in our series.

For the original study, copy number variants were classified as common benign, variants of unknown clinical significance, or known pathogenic. Frequently observed benign copy-number variants present in our own databases of copy-number variants detected in the course of postnatal analysis, in peer-reviewed publications, and in curated databases of apparently unaffected persons were classified as “common benign”. For purposes of this analysis all copy number variants other than those classified as common benign were included. These include “pathogenic copy number variants” of any size encompassing a region implicated in a well-described abnormal phenotype and any CNV >1 megabase regardless of location. (n=61) (1). In all cases, microarray analysis of DNA from maternal and paternal blood samples was used to determine whether copy number variants detected in the fetal samples were inherited or de-novo. We confirmed all de novo array findings by a second method. Further information outlining this is available in Appendix 3, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx.

Frequencies of ultrasound-detected fetal anomalies in the major anatomical systems were tabulated showing genetic abnormalities diagnosed by karyotype and additional copy number variants seen on array. The value of findings provided by microarray, referred to as “incremental yield” was calculated as the percentage of patients with a normal karyotype who had microarray findings that were other-than-common benign. This was calculated by category and subcategory for each anomaly according to whether the anomaly was found in isolation or in the presence of anomalies in other organ systems. Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test were used to compare the incremental yield of CMA in the group with ultrasound anomalies with the control group whose indication was advanced maternal age. All tests were two-tailed and P<0.05 was used to define nominal statistical significance. Since this is a secondary, exploratory analysis, unadjusted p-values have been reported in the text and tables. However, when a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons is applied the threshold for significance is p=0.001 (0.05/49),. The Bonferroni is based on independent tests, therefore the count of tests includes comparisons for 11 anatomical systems and 38 anatomical subcategories for larger organ systems in tables listing ultrasonographically detected anomalies.. SAS software (SAS Institute) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

There were 1,082 pregnancies with ultrasonographically detected structural abnormalities. In this cohort, gestational age at procedure ranged from 10 weeks to 38 weeks, with a median of 18 weeks. Of these 398 (36.8%) women had their invasive prenatal diagnosis prior to 14 weeks.

Seven-hundred and fifty-two fetuses (69.5%) had a normal karyotype. The frequency of other-than-common benign copy number variants in fetuses with ultrasonographically detected structural anomalies was significantly higher than in fetuses without anomalies (61/752, 8.1% vs. 71/1966, 3.6%, p<0.001). The breakdown of copy number variants for the anomaly group and the advanced maternal age group is shown in Table 1. The full list of copy number variants included in this analysis and their associated ultrasound findings is available in the Appendix 3 (http://links.lww.com/xxx).

Table 1.

Frequency and Clinical Interpretation of Copy Number Variants in Study Group (Ultrasonographic Anomaly) and Control Group (Advanced Maternal Age)

| Indication | Normal Karyotype | Common Benign | Pathogenic | Variants of Unknown Significance | Total Known Pathogenic and VOUS | Total Other Than Common Benign | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Likely Benign | Potential for Clinical Significance | With Potential For Clinical Significance | |||||

|

| |||||||

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (b+d) | (b+c+d) | ||

| Anomaly on ultrasound | 752 | 247 (32.8%) | 21 (2.8%) | 16 (2.1%) | 24 (3.2%) | 45 (6.0%) | 61(8.1%) |

| (1.6 –4.0) | (1.1 – 3.2) | (1.9 – 4.5) | (4.3 – 7.7) | (6.2 – 10.1) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Advanced maternal age | 1966 | 628(31.9%) | 9 (0.5%) | 37 (1.9%) | 25 (1.3%) | 34 (1.7%) | 71(3.6%) |

| (0.2 – 0.8) | (1.3 – 2.5) | (0.8 – 1.8) | (1.2 – 2.3) | (2.8 – 4.4) | |||

|

| |||||||

| P-value* | <0.001 | 0.679 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

Data are n, n (%), or 95% CI unless otherwise specified. VOUS, variants of unknown significance; CI, confidence interval.

(a) common benign, (b) pathogenic, (c) VOUS – likely benign, (d) VOUS- potential for clinical significance

P-values are based on a comparison of the proportion of cases with copy number variants in the ultrasonographic anomaly and advanced maternal age study groups.

Among the 752 fetuses with anomalies and a normal karyotype, 498 and 254 had an abnormality in single or multiple organ systems, respectively (Table 2). Twenty-eight fetuses (5.6%) with anomalies confined to a single organ system had an other-than-common benign CNV; this frequency was nominally statistically different from that in the AMA control group (3.6%, p=0.4). However, the most frequent ultrasonographic abnormalities among our cohort of patients were abnormalities of the nuchal area used primarily for aneuploidy screening and included an increased nuchal translucency of ≥3.5mm, a nuchal fold of >6mm and/or a cystic hygroma. When these findings were isolated (n=186), the frequency of copy number variants (N = 7, 3.8%) was comparable to that in the control group. When fetuses with these diagnoses were excluded from the overall analysis of isolated structural anomalies, the frequency of copy number variants (n = 21, 6.7%) was nominally significantly greater (p=0.009) than in the control group (Table 2). Fetuses with anomalies in more than one system (N = 254) had a 13.0% frequency of other-than-common benign copy number variants, which was significantly higher (p<0.001) than that seen in the control group.

Table 2.

Frequency of All Other-Than-Common Benign Copy Number Variants Associated With Ultrasonographically Detected Abnormalities

| Anomaly System | N=752 | CNV Array Findings (n) | % CNV (95% CI) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All anomalies | ||||

|

| ||||

| Isolated | 498 | 28 | 5.6% (3.6 – 7.7) | 0.041 |

| Multiple | 254 | 33 | 13.0% (8.9 – 17.1) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Excluding neck anomalies | ||||

|

| ||||

| Isolated | 312 | 21 | 6.7% (4.0 – 9.5) | 0.009 |

| Multiple | 206 | 28 | 13.6% (8.9 – 18.3) | <0.001 |

Compared to frequency of CNV among women with advanced maternal age and no fetal anomalies (n = 71/1966, 3.6%).

CNV, copy number variant; CI, confidence interval.

Table 3 shows the frequency of all ultrasonographically detected abnormalities detected in karyotypically normal pregnancies (n=752) classified by system and by whether the anomaly was isolated. The greatest incremental yield for CMA was seen for cardiac anomalies (15.6%, p<0.001), facial abnormalities (15.2%, p<0.001), and intrathoracic abnormalities (15.0%, p=0.004), including all cases whether single or multiple. Of abnormalities seen only in a single organ system, isolated renal and cardiac anomalies were associated with the greatest nominally significant incremental yield provided by CMA (15.0%, p=0.036 and 10.6%, p=0.012, respectively). Although isolated anomalies in other organ systems were associated with point estimates for the incremental benefit of microarray that were greater than that in the control group, the numbers in these groups were small and the differences between groups were not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Frequency of Ultrasonographically Detected Anomalies by Anatomical System in Karyotypically Normal Pregnancies

| ALL (n=752) | Isolated | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Ultrasound Anomaly | n† | Array CNVs(n) | IncrementalYield (%) | P | n | Array CNVs(n) | IncrementalYield (%) | P |

| Cardiac | 154 | 24 | 15.58% | <0.001‡ | 66 | 7 | 10.61% | 0.012* |

| Face | 66 | 10 | 15.15% | <0.001*‡ | 20 | 2 | 10.00% | - |

| Thorax | 40 | 6 | 15.00% | 0.004* | 22 | 1 | 4.55% | - |

| Amniotic Fluid | 44 | 6 | 13.64% | 0.006* | 2 | 1 | 50.00% | - |

| Head shape | 23 | 3 | 13.04% | - | 6 | 0 | ||

| Umbilical | 32 | 4 | 12.50% | 0.03* | 0 | 0 | ||

| Renal | 69 | 8 | 11.59% | 0.004* | 20 | 3 | 15.00% | 0.036* |

| Gastrointestinal | 37 | 4 | 10.81% | 0.047* | 5 | 0 | ||

| Central nervous system | 149 | 14 | 9.40% | <0.001‡ | 63 | 2 | 3.17% | - |

| Skeletal | 136 | 12 | 8.82% | 0.003 | 36 | 1 | 2.78% | - |

| Genital | 12 | 1 | 8.33% | - | 3 | 0 | ||

| Effusion | 65 | 4 | 6.15% | - | 15 | 1 | 6.67% | - |

| Spine | 18 | 1 | 5.56% | - | 2 | 0 | ||

| Neck | 236 | 12 | 5.08% | - | 187 | 7 | 3.74% | - |

| Neck (excluding NT>3.5mm, NF>6mm, and cystic hygroma) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Abdominal wall | 40 | 1 | 2.50% | - | 24 | 0 | ||

| Ear | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Placenta | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

CNVs, copy number variants; NT = nuchal translucency; NF= nuchal fold,.

Numbers add up to >752, as each fetus may have anomalies in more than one system.

P-value calculated using Fisher’s Exact test.

Bonferroni correction threshold: p=.001.

Table 4 shows the frequency of ultrasound observed abnormalities and genetic anomalies sub-classified by abnormalities of each organ system. Of particular note, cardiac abnormalities were classified into subgroups depending on the ultrasound appearance of the anomalies: abnormalities of the 4-chamber view, of the outflow tracts and specific diagnoses. When outflow tract abnormalities were the only ultrasound finding, there was an incremental benefit of CMA of 30.0% (p=0.005). Of note is that the CMA findings were not predominantly 22q11.2 deletions (which can be detected using karyotype analysis with targeted FISH). Alternatively, 66.7% (16/24) of patients with cardiac defects had copy number variants other than a 22q11.2 deletion. When fetuses with a 22q.11.2 deletion were excluded from analysis, copy number variants were still significantly more common in fetuses with any cardiac defects (n= 16, 11.0%, p<0.001) or in those with isolated outflow tract abnormalities (n=3, 30.0%, p=0.005) than in the structurally and karyotypically normal fetuses of women of advanced maternal age. Table 5 summarizes the frequency of the commonly seen copy number variants in our series. The majority of other-than-common benign copy number variants (50.8%) only occurred once.

Table 4.

Frequency of All Ultrasonographically Detected Abnormalities, Showing Abnormal Karyotypes From G-Banding and Additional Array Findings, by Anatomical Systems and Subcategories

| Anomaly | n† | Abnormal Karyotype | CNV by Array | Normal Karyotype | Incremental Yield | P-Value (Chi-Square or Fisher) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac+ | 232 | 78 | 24 | 154 | 15.58% | <0.001‡ |

| Cardiac (Single) | 76 | 10 | 7 | 66 | 10.61% | 0.012* |

|

| ||||||

| Four-chamber abnormality (no other heart anomalies) | 136 | 50 | 11 | 86 | 12.79% | <0.001*‡ |

| Four-chamber abnormality (single) | 39 | 4 | 2 | 35 | 5.71% | - |

| Outflow abnormality (no other heart anomalies) | 25 | 8 | 5 | 17 | 29.41% | <0.001*‡ |

| Outflow abnormality (single) | 11 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 30.00% | 0.005* |

| Tetralogy of Fallot (single) | 9 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 16.67% | - |

| Double outlet right ventricle (single) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Heterotaxy | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Face | 108 | 42 | 10 | 66 | 15.15% | <0.001*‡ |

| Face (single) | 21 | 1 | 2 | 20 | 10.00% | - |

|

| ||||||

| Cleft Lip and/or palate | 42 | 17 | 3 | 25 | 12.00% | - |

| Cleft lip (single) | 6 | 1 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Cleft palate (single) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Profile | 44 | 14 | 5 | 30 | 16.67% | 0.005* |

| Profile (single) | 6 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 16.67% | - |

| Frontal bossing | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | ||

| Frontal bossing (single) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Micrognathia | 25 | 10 | 3 | 15 | 20.00% | 0.016* |

| Micrognathia (single) | 5 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 20.00% | - |

| Profile flat | 9 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 33.33% | 0.018* |

| Profile flat (single) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Thorax | 50 | 10 | 6 | 40 | 15.00% | 0.004* |

| Thorax (single) | 22 | 0 | 1 | 22 | 4.55% | - |

|

| ||||||

| Congenital diaphragmatic hernia | 36 | 6 | 3 | 30 | 10.00% | - |

| Cystic lung lesion | 6 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 16.67% | - |

| Hypoplastic thorax | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Renal tract | 93 | 24 | 8 | 69 | 11.59% | 0.004* |

| Renal tract (single) | 20 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 15.00% | 0.036* |

|

| ||||||

| Hydronephrosis | 37 | 14 | 3 | 23 | 13.04% | - |

| Hydronephrosis (single) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Large/multicystic kidney | 41 | 7 | 6 | 34 | 17.65% | 0.002* |

| Bladder | 22 | 5 | 2 | 17 | 11.76% | - |

| Renal agenesis | 6 | 2 | 0 | 4 | ||

|

| ||||||

| CNS | 200 | 51 | 14 | 149 | 9.40% | <0.001‡ |

| CNS (Single) | 71 | 8 | 2 | 63 | 3.17% | - |

|

| ||||||

| Neural tube defects (no other CNS anomalies) | 30 | 8 | 0 | 22 | ||

| Neural tube defects with ventriculomegaly | 8 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 25.00% | 0.033* |

| Posterior Fossa defects (no other CNS anomalies) | 37 | 9 | 0 | 28 | ||

| Posterior Fossa defects with ventriculomegaly | 11 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 20.00% | 0.05* |

| Holoprosencephaly | 17 | 12 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Any other CNS defects only | 9 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 20.00% | - |

| Ventriculomegaly | 93 | 12 | 12 | 81 | 14.8% | <0.001‡ |

| Ventriculomegaly (single) | 24 | 1 | 2 | 23 | 8.7% | - |

|

| ||||||

| Skeletal | 193 | 57 | 12 | 136 | 8.82% | 0.003 |

| Skeletal (Single) | 39 | 3 | 1 | 36 | 2.78% | - |

|

| ||||||

| Skeletal dysplasia | 22 | 2 | 0 | 20 | ||

| Joint (excluding skeletal dysplasia) | 89 | 27 | 7 | 62 | 11.29% | 0.008* |

| Long bones (excluding skeletal dysplasia) | 66 | 22 | 5 | 44 | 11.36% | 0.023* |

| Long bones or Joint (excluding skeletal dysplasia) | 136 | 42 | 11 | 94 | 11.70% | <0.001*‡ |

| Long bones or joint (excluding skeletal dysplasia, foot, hand, and ribs) | 108 | 32 | 8 | 76 | 10.53% | 0.008* |

| Talipes (excluding skeletal dysplasia) | 72 | 17 | 5 | 55 | 9.09% | 0.053* |

| Talipes (single) | 14 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 7.14% | - |

n†,= numbers add up to >752 as each fetus may have anomalies in more than one subcategory.

CNV, copy number variant.

Four-chamber view =anomalous pulmonary venous return, atrial septal defect, AV canal defect, dextrocardia, Ebstein’s anomaly, cardiac tumor, hypolastic left or right heart, ventricular septal defect, other abnormal four-chamber view not otherwise specified; outflow tracts = aortic stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, interrupted aortic arch, transposition of the great arteries, truncus arteriosus, abnormal outflow tracts not otherwise specified.

P-value calculated using Fisher’s Exact test.

Bonferroni correction threshold: p=.001.

Table 5.

Frequency of Copy Number Variants Seen in Patients With Ultrasonographically Detected Anomalies

| CNV | Deletion | Duplication | Total (N=61) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22q11.21 | 10 | 1 | 11 | 18.0% |

| 17q12 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 9.8% |

| 16p13.11 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 9.8% |

| 1q21.1 | - | 3 | 3 | 4.9% |

| 10q21.1 | 2 | - | 2 | 3.3% |

| 15q13.3* | - | 2 | 2 | 3.3% |

| Single occurrence | 17 | 14 | 31 | 50.8% |

Two patients had two separate copy number variants identified, however this table counts only 1 copy number variant per patient. A third duplication of 15q13.3 was seen in conjunction with the 22q11.21 duplication listed in the table, and one patient had 2 single-occurrence copy number variants.

DISCUSSION

We have confirmed that CMA increases the detection of prenatally diagnosed genomic abnormalities in women with recognized fetal anomalies. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal--Fetal Medicine now recommend that CMA be performed in lieu of karyotyping in pregnancies with an anomalous fetus undergoing invasive testing (1, 2, 4, 5). In this study, we have demonstrated that this increased detection depends on the number and type of anomaly. Copy number variants are more likely when the fetus has multiple anomalies and in those with isolated anomalies, the greatest yield occurs in cardiac and renal anomalies. This information should be of value in patient counseling and pregnancy management.

These findings extend the work of others (2). For example, in an analysis of CMA results from 2828 women, clinically significant copy number variants were seen in 6.5% of fetuses with anatomic anomalies (4); a frequency similar to that seen in our study. In that series, CMA was particularly informative when craniofacial and cardiac malformations were seen. However, a direct comparison to this study is not possible since almost a quarter of cases in the report had large copy number variants but no available karyotype, making it impossible to quantify the incremental value of microarray.

One of the strengths of our analysis is the prospective data collection. All consecutive patients with anomalous fetuses were offered simultaneous microarray analysis at the time of invasive testing. Retrospective studies from referral genetic laboratories include selected patients, some of whom had CMA to improve the interpretation of a previously characterized karyotype (4). Another study strength was the expertise of the ultrasonographers. All 29 sites were AIUM accredited and followed standardized guidelines (6). Additionally, a standardized array design was utilized for all cases.

Although our study is large, it was not powered to address the association of specific deletions with specific ultrasound abnormalities. Indeed, over half of the copy number variants detected occurred only once. In order to enhance the clinical usefulness of CMA, it is essential to continue to collect additional phenotype-genotype correlations. The large number of relatively rare copy number variants associated with anomalies demonstrates that use of targeted arrays containing only a limited number of well-described copy number variants is not sufficient. For example, when a cardiac defect is detected, limiting analysis to karyotyping and FISH for the common 22q11.2 deletion would fail to identify over two thirds of the genomic findings.

To quantify the incremental value of microarray testing in anomalous fetuses, we compared them to structurally normal fetuses being sampled for AMA.. Since copy number variants are not age related this is an appropriate comparison group representing the population risk of a CNV. This AMA group had a rate of other-than-common benign copy number variants of 3.6%; much lower than those with structural anomalies. Since 61% of these cases were sampled in the first trimester, it is possible that some could have had anomalies undetected at the time of sampling. However, if this were the case, it would bias the study toward the null hypothesis; thus, the increase in information provided by CMA in the presence of a fetal anomaly is, if anything, underestimated.

In our analysis, all variants of uncertain significance were included rather than attempting to classify some as likely pathogenic and others as likely benign. We believe this is the best approach since the field and our knowledge of phenotype-genotype correlations is still evolving. While this may slightly overestimate the frequency of clinically relevant copy number variants, it allows comparison of the two groups without concern for bias based on scan results.

Cytogenomic information revealed by CMA has clinical benefit. In many cases the etiology of a structural anomaly is unknown and patients are left to make decisions on pregnancy management based on uncertainty as to the long-term prognosis. Identification of a CNV allows a more precise understanding of the medical and neurocognitive implications of the anomaly which is important in decision making about the pregnancy and in planning care for the child.

In summary, when a fetal anomaly is detected on ultrasound, CMA offers additional information compared with karyotype, with the degree of benefit dependent on the type and number of organ systems involved. Further research using pooled databases is required to provide more precise point estimates of the frequency of copy number variants associated with specific types of anomalies. An ongoing long-term follow up of the original NICHD study population will allow better correlation between prenatally detected copy number variants and the subsequent phenotype. There appears to be clear value of CMA in the evaluation of fetal structural anomalies, and this study confirms that it should be offered when anomalies are diagnosed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Secondary analysis of primary research supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD05565101, R01HD055651-03S1, and RC2HD064525).

The authors thank Cartagenia for the use of their web-based software, the Cartagenia BENCH™ database; Michelle DiVito (Columbia University Medical Center), Anthony Johnson (Texas Fetal Center, UT-Health), and Melissa Savage for their help in data gathering and in preparation of this manuscript; Nicolasa H. Chavez, Jessica Feinberg, and Andrea M. Murad for their coordination and recruitment efforts; Elizabeth Thom, Ph.D. and Vinay Bhandaru (the George Washington University Biostatistics Center) for providing leadership and conducting the statistical analysis at the Data Coordinating Center; the laboratory technologists, including Emily Carron from Columbia University, Vanessa Jump from Emory University, Caron Glotzbach from Signature Genomic Laboratories, PerkinElmer, and Patricia Hixson at Baylor College of Medicine;; and the participants and the North American Fetal Therapy Network for their support of the study. The authors also thank the participant recruitment sites, a full listing of which can be found at in Appendix 1 at http://links.lww.com/xxx.

Footnotes

Presented at the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis on June 5th 2013, in Lisbon, Portugal.

Financial Disclosure: Lawrence D Platt is on the Clinical Advisory Board and a Consultant to Illumina. Andrei Rebarber has served on the advisory board for Natera and is on the speakers list for Alere. Ronald J Wapner is a Principal Investigator on studies funded by Natera, Ariosia, Sequenom, and Illumina, and has been a speaker for Natera and Ariosia The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wapner RJ, Martin CL, Levy B, Ballif BC, Eng CM, Zachary JM, et al. Chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(23):2175–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203382. Epub 2012/12/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillman SC, McMullan DJ, Hall G, Togneri FS, James N, Maher EJ, et al. Use of prenatal chromosomal microarray: prospective cohort study and systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013;41(6):610–20. doi: 10.1002/uog.12464. Epub 2013/03/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper GM, Coe BP, Girirajan S, Rosenfeld JA, Vu TH, Baker C, et al. A copy number variation morbidity map of developmental delay. Nature genetics. 2011;43(9):838–46. doi: 10.1038/ng.909. Epub 2011/08/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaffer LG, Rosenfeld JA, Dabell MP, Coppinger J, Bandholz AM, Ellison JW, et al. Detection rates of clinically significant genomic alterations by microarray analysis for specific anomalies detected by ultrasound. Prenatal diagnosis. 2012;32(10):986–95. doi: 10.1002/pd.3943. Epub 2012/08/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Committee Opinion No. 581: the use of chromosomal microarray analysis in prenatal diagnosis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;122(6):1374–7. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000438962.16108.d1. Epub 2013/11/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AIUM practice guideline for the performance of obstetric ultrasound examinations. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2013;32(6):1083–101. doi: 10.7863/ultra.32.6.1083. Epub 2013/05/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.