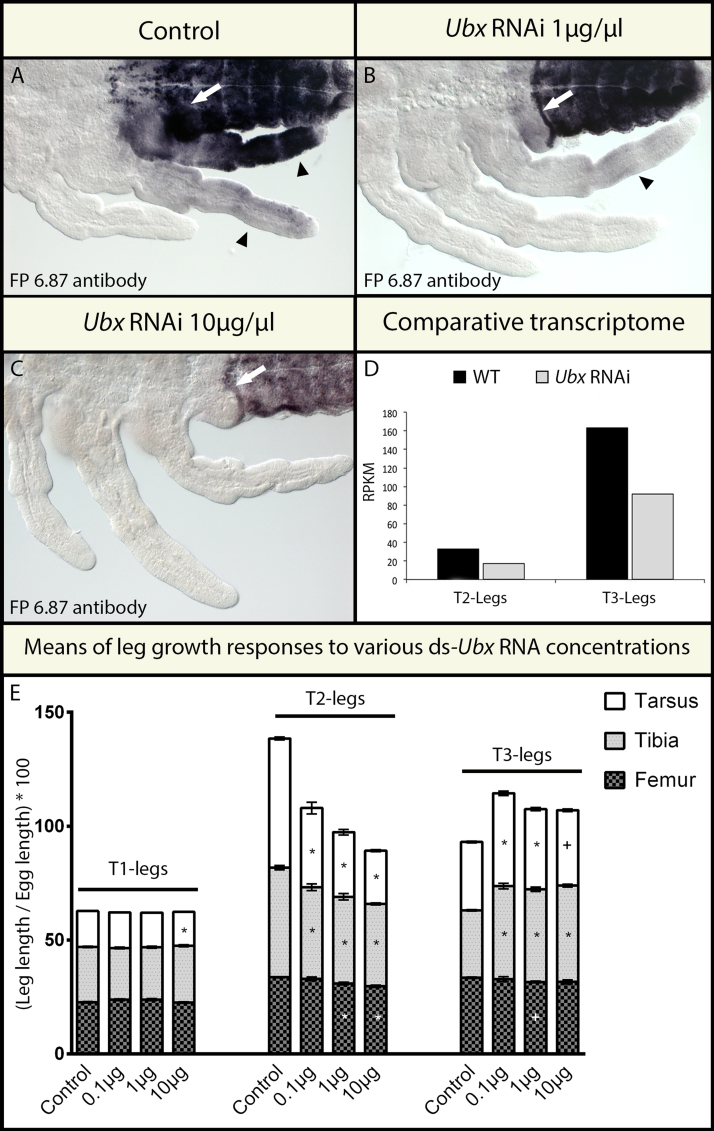

Fig. 3.

Effect of RNAi on Ubx levels and on leg length in Limnoporus embryos. (A) Anti-UbdA staining is unaffected in control embryos and shows faint Ubx expression in T2-legs and stronger expression in T3-legs. In the abdomen, the anterior-most boundary of Abd-A is masked by the strong expression of Ubx (white arrow). (B) When a 1 μg/μl concentration of ds-Ubx was injected, Ubx is now undetectable in T2- and becomes faint in T3-legs. Note that the anterior-most boundary of Abd-A has now become sharp due to faint Ubx in abdominal segment A1 (white arrow). (C) When the even higher 10 μg/μl concentration of ds-Ubx was injected, Ubx is now undetectable in T2-legs, T3-legs, or in the abdomen. The anterior-most boundary of Abd-A remains intact (white arrow). Because Ubx is also expressed in abdominal segments and contributes to the strong signal there (Fig. 2A), the strong depletion of Ubx results in a lower signal in the abdomen, even when the reaction is left to develop longer. (D) Quantification, using deep sequencing, of the efficiency of Ubx transcript depletion in response to Ubx RNAi (pool of embryos from a ~2 μg/μl treatment). Ubx is depleted approximately by half and this depletion is uniform in T2- and T3-legs, such that the difference in Ubx levels remains between the two legs. (E) Growth response of T2- and T3-legs to the injection of increasing concentrations of ds-Ubx. * indicates statistical significance at P≤0.01 and + at P≤0.05. N=10 in all samples.