Abstract

Objectives

Recent scholarly attention has focused on explicating the nature of tobacco use among anxiety-vulnerable smokers. Anxiety sensitivity (fear of aversive internal anxiety states) is a cognitive-affective individual difference factor related to the development and maintenance of anxiety symptoms and disorders and various smoking processes. The present study examined the cross-sectional associations between anxiety sensitivity and a range of cognitive and behavioral smoking processes, and the mediating role of the tendency to respond inflexibly and with avoidance in the presence of smoking-related distress (AIS; thoughts, feelings, or internal sensations) in such relations.

Method

Participants (n = 466) were treatment-seeking daily tobacco smokers recruited as part of a larger tobacco cessation study. Baseline (pre-treatment) data were utilized. Self-report measures were used to assess anxiety sensitivity, AIS, and four criterion variables: Barriers to smoking cessation, quit attempt history, severity of problematic symptoms reported in past quit attempts, and mood-management smoking expectancies.

Results

Results indicated that anxiety sensitivity was indirectly related to greater barriers to cessation, greater number of prior quit attempts and greater mood-management smoking expectancies through the tendency to respond inflexibly/avoid to the presence of distressing smoking-related thoughts, feelings and internal sensations; but not severity of problems experienced while quitting.

Discussion

The present findings suggest AIS may be an explanatory mechanism between anxiety sensitivity and certain smoking processes.

Keywords: anxiety sensitivity, tobacco, psychological inflexibility, avoidance

Anxiety disorders are among the most common psychiatric conditions (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005) and numerous clinical and epidemiological studies indicate higher rates of smoking among the anxiety-disordered population relative to both persons with no psychiatric illness as well as many other psychiatric conditions (Lasser et al., 2000; McCabe et al., 2004). One means of elucidating the role of anxiety in cigarette use is to investigate the influence of transdiagnostic psychological vulnerability factors that underlie anxiety-related conditions on smoking. Anxiety sensitivity, conceptualized as an individual difference factor related to sensitivity to aversive internal states of anxiety (McNally, 2002; Reiss, Peterson, Gursky, & McNally, 1986), has been implicated in the development and maintenance of panic attacks, anxiety/depressive symptoms, and emotional disorders (e.g., panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder; Hayward, Killen, Kraemer, & Taylor, 2000; Maller & Reiss, 1992; McNally, 2002; Marshall, Miles, & Stewart, 2010; Schmidt, Lerew, & Jackson, 1999; Schmidt, Zvolensky, & Maner, 2006; Taylor, 2003). Importantly, AS is distinguishable empirically and theoretically from trait or state anxiety symptoms and other negative affect states (e.g., depression; Rapee & Medoro, 1994).

More recent research indicates anxiety sensitivity is related to smoking behavior. For example, higher levels of anxiety sensitivity are associated with smoking motives to reduce negative affect (Battista et al., 2008; Comeau, Stewart, & Loba, 2001;) and negative affect reduction expectancies (beliefs that smoking will reduce negative affect; Johnson, Farris, Schmidt, Smits, & Zvolensky, 2013). Recent research also suggests that high levels of anxiety sensitivity are predictive of greater increases in positive affect pre- to post-cigarette use (Wong et al., 2013) and that among high anxiety sensitive smokers (relative to low anxiety sensitive smokers), cigarette smoking after stressful situations reduces subjective anxiety (Evatt & Kassel, 2010; Perkins, Karelitz, Giedgowd, Conklin, & Sayette, 2010).

From a cessation perspective, smokers higher relative to lower in anxiety sensitivity perceive quitting as more difficult (Johnson et al., 2013) and may experience more intense nicotine withdrawal during early phases in quitting (i.e., one week post quit; Johnson, Stewart, Rosenfield, Steeves, & Zvolensky, 2012), but not necessarily withdrawal in later phases of quitting (Mullane, Stewart, Rhyno, Steeves, Watt, & Eisner, 2008). Higher levels of anxiety sensitivity are also related to greater odds of early lapse (Brown, Kahler, Zvolensky, Lejuez, & Ramsey, 2001) and relapse during quit attempts (Assayag, Bernstein, Zvolensky, Steeves, & Stewart, 2012). Additionally, reductions in anxiety sensitivity appear to be related to increased rates of cessation success (Zvolensky, Yartz, Gregor, Gonzalez, & Bernstein, 2008). Importantly, the observed anxiety sensitivity-smoking effects do not appear to be explained by smoking rate, nicotine dependence, gender, other concurrent substance use (e.g., alcohol, cannabis), panic attack history, or trait-like negative mood propensity (Johnson et al., 2013; Wong et al., 2013).

Notably, with few exceptions, extant work has not yet explored processes that may mediate the relation between anxiety sensitivity and smoking. While past work has shown that the global emotion dysregulation construct may mediate the association between anxiety sensitivity and certain cognitive-based smoking processes (e.g., Johnson, Farris, Schmidt, & Zvolensky, 2012), no work has explored smoking-specific aspects of emotion regulation. This limitation is unfortunate, as there is a growing recognition that how one responds to aversive internal or emotional states (perceived and/or actual) may play a central role in cognitive-affective smoking processes (e.g., mood/addiction management smoking motives; Leyro, Zvolensky, Vujanovic, & Bernstein, 2008) and cessation behavior. For example, smokers with a greater ability to tolerate or withstand aversive somatic distress are less likely to lapse after a self-guided cessation attempt (Brown et al., 2009). In contrast, those smokers with a lower threshold for tolerating such distress have shorter durations of smoking abstinence after attempting cessation (Brown et al., 2009; Hajek, Belcher, & Stapleton, 1987; West, Hajek, & Belcher, 1989). The latter group of smokers may be particularly prone to inflexibly seek out opportunities to escape, avoid, or reduce distressing states, and do so through smoking (Gifford & Lillis, 2009; Parrott, 1999). This process has been termed as smoking inflexibility/avoidance (AIS: avoidance and inflexibility to smoking), and is conceptualized as a smoking-specific form of experiential avoidance (Gifford & Lillis, 2009). Similar to other forms of escape/avoidance behavior, AIS is thought to be a negative reinforcement process that is rooted in the dopaminergic reward system, which governs the dopamine release in the mesolimbic pathway (Trafton & Gifford, 2008, 2011). Interestingly, smoking cessation intervention programs have been developed to specifically cultivate greater willingness for emotional distress tolerance/acceptance to address AIS, and emerging results suggest such interventions generally produce better clinical outcomes compared to standard care (Bricker, Mann, Marek, Liu, & Peterson, 2010; Brown et al., 2008, 2013; Gifford et al., 2004; Hernandez-Lopez, Luciano, Bricker, Roales-Nieto, & Montesinos, 2009). Together, there are numerous lines of work that suggest an inflexible, avoidant response to smoking-related aversive thoughts, feelings, or internal states (e.g., withdrawal symptoms) is of potential clinical importance in better understanding processes governing the maintenance and relapse of smoking. This type of smoking-specific construct is likely related to other more general factors such as experiential avoidance and perhaps distress tolerance (Gifford et al., 2004). Yet, it is unclear if anxiety sensitivity is related to AIS.

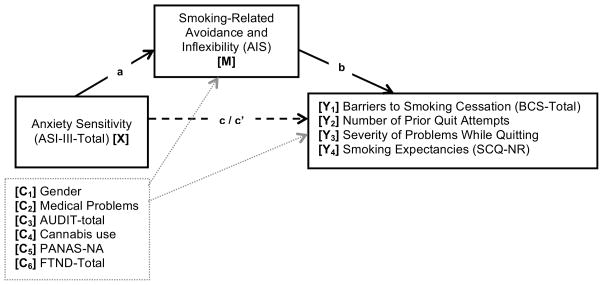

Building from past theory and research, we sought to examine whether the tendency to respond inflexibility/avoid by smoking in the presence of distressing smoking-related thoughts, feelings and internal sensations (AIS) mediates the relation between anxiety sensitivity and a range of smoking processes. Specifically, among treatment-seeking smokers, we examined whether the relations between anxiety sensitivity and (1) perceived barriers to quitting smoking, (2) failed quit attempts, (3) severity of problematic symptoms during past quit attempts, and (4) negative reinforcement smoking expectancies, were mediated by AIS (see Figure 1). We adjusted for level of nicotine dependence, alcohol use, cannabis use status, negative affectivity, and tobacco-related medical problems in the models to make ensure that the observed effects were not attributable to these factors.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of mediation analyses

Notes: a = Effect of X on M; b = Effect of M on Yi; c′i = Direct effect of X on Yi controlling for M; a*b = Indirect effect of M; four separate models were conducted for each criterion variable (Y1–4).

Method

Participants

Participants (n = 466) were adult treatment-seeking daily smokers (Mage = 36.6, SD = 13.58; 48.5% female). Inclusion criteria for the parent study included daily cigarette use (average ≥ 8 cigarettes per day for at least 1 year), between ages 18–65, and reported motivation to quit smoking of at least 5 on a 10-point scale. Exclusion criteria included: inability to give informed consent, current use of smoking cessation products or treatment, past-month suicidality, and history of psychotic-spectrum disorders.

Measures

Demographics Questionnaire

Demographic information collected included gender, age, race, educational level, marital status, and employment status. These data were used for descriptive purposes and gender was entered as a covariate in all analyses.

Structured Clinical Interview-Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV (SCID-I/NP; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002)

Diagnostic assessments of past year Axis I psychopathology were conducted using the SCID-I/NP, which were administered by trained research assistants or doctoral level staff and supervised by independent doctoral-level professionals. Interviews were audio-taped and the reliability of a random selection of 12.5% of interviews were checked (MJZ) for accuracy; no cases of (diagnostic coding) disagreement were noted.

Smoking History Questionnaire (SHQ)

The SHQ (Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, & Strong, 2002) is a self-report questionnaire used to assess smoking history (e.g., onset of regular daily smoking) and pattern (e.g., number of cigarettes consumed per day), strategies use to quit and problematic symptoms experienced during past quit attempts (e.g., weight gain, nausea, irritability, and anxiety; Brown et al., 2002). In the present study, the SHQ was employed to describe the sample on smoking history and patterns of use (e.g., smoking rate), and then to create two criterion variables: (1) number of prior quit attempts and (2) mean composite score of severity of problem symptoms experienced during past quit attempts (for those who reported ≥ 1 lifetime quit attempt).

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)

The FTND (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991) is a 6-item scale that assesses gradations in tobacco dependence. Scores range from 0–10, with higher scores reflecting high levels of physiological dependence on nicotine. The FTND has adequate internal consistency, positive relations with key smoking variables (e.g., saliva cotinine), and high test-retest reliability (Heatherton et al., 1991; Pomerleau, Carton, Lutzke, Flessland, & Pomerleau, 1994). The FTND total score was used as a covariate in the present study and internal consistency was found to be acceptable (Cronbach’s α = .642).

Medical History Form

A medical history checklist was used to assess current and lifetime medical problems. A composite variable was computed for the present study as an index of tobacco-related medical problems, which was entered as a covariate in all models. Items in which participants indicated having ever been diagnosed (heart problems, hypertension respiratory disease and asthma; all coded 0 = no, 1 = yes) were summed and a total score was created (observed range from 0 – 3), with greater scores reflecting the occurrence of multiple markers of tobacco-related disease.

Anxiety Sensitivity Index-III (ASI-III; Taylor et al., 2007)

The ASI-III is an 18-item measure in which respondents indicate the extent to which they are concerned about possible negative consequences of anxiety-related symptoms (e.g., “It scares me when my heart beats rapidly”). Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (very little) to 4 (very much) and summed to create a total score. The ASI-III has strong and improved psychometric properties relative to previous measures of the construct (Taylor et al., 2007). In the present investigation, the total score was utilized as a primary predictor variable; internal constancy was excellent in the current sample (Cronbach’s α = .928).

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)

The AUDIT (Babor, de la Fuente, Saunders, & Grant, 1992) is a 10-item self-report measure developed to identify individuals with alcohol problems. Total scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores reflecting more hazardous drinking. The psychometric properties are well documented. In the present study, the AUDIT total score was used as a covariate in all analyses; internal consistency was good (Cronbach’s α = .839).

Marijuana Smoking History Questionnaire (MSHQ)

The MSHQ (Bonn-Miller & Zvolensky, 2009) is a 40-item measure that assesses cannabis use history and patterns of use. One item was used in the current study to determine status of marijuana use in the past 30 days: “Please rate your marijuana use in the past 30 days” (Responses range from 0 = No use, 4 = Once a week, to 8 = More than once a day). This item was dichotomously coded to reflect a marijuana use status variable (0 = No use; 1 = Past 30-day use), which was entered as a covariate in all analyses.

Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS)

The PANAS (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) is a self-report measure that requires participants to rate the extent to which they experience each of 20 different feelings and emotions (e.g., nervous, interested) based on a Likert scale that ranges from 1 (“Very slightly or not at all”) to 5 (“Extremely”). The measure yields two factors, negative and positive affect, and has strong documented psychometric properties (Watson et al., 1988). The negative affectivity subscale was used as a covariate in the present study; internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s α = .902).

Acceptance and Inflexibility Scale (AIS)

The AIS (Gifford et al., 2004) is a 13-item self-reported measured that assess the link between internal (affective) triggers and smoking (smoking-related inflexibility/avoidance). Instructions ask the respondents to consider how they respond to difficult thoughts that encourage smoking (e.g., “I need a cigarette”), different feelings that encourage smoking (e.g., stress, fatigue, boredom), and bodily sensations that encourage smoking (e.g., “physical cravings or withdrawal symptoms”). Example items include “How likely is it you will smoke in response to [thoughts/feelings/sensations]?”, “How important is getting rid of [thoughts/feelings/sensations]?”, and “To what degree must you reduce how often you have these [thoughts/feelings/sensations] in order not to smoke?”. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all to 5 = Very much), with higher scores reflecting more inflexibility/avoidance in the presence of difficult smoking-related thoughts, feelings, and sensations. The AIS has displayed good reliability and validity in past work (Gifford et al., 2004; Gifford, Ritsher, McKellar, & Moos, 2006). The AIS total score was used as the mediator variable as an index of smoking inflexibility/avoidance; internal consistency was excellent in the present sample (Cronbach’s α = .925).

Barriers to Cessation Scale (BCS)

The BCS (Macnee & Talsma, 1995) is a self-report assessment of perceived barriers associated with quitting smoking. Specifically, the BCS is a 19-item measure on which respondents indicate, on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = Not a barrier or not applicable to 3 = Large barrier), the degree to which they identify with each listed barriers (e.g., “Weight gain,” “Friends encouraging you to smoke,” “Fear of failing to quit”). Scores are summed and a total score is derived. The BCS has strong psychometric properties, including continent and predictive validity, internal consistency, and reliability (Macnee & Talsma, 1995). The BCS total score was used as a criterion variable in the present study; Cronbach’s α = .890).

Smoking Consequences Questionnaire (SCQ; Brandon & Baker, 1991)

The SCQ is a 50-item self-report measure that assesses smoking expectancies on a 10-point scale for likelihood of occurrence (0 = completely unlikely to 9 = completely likely). The entire measure and its constituent factors have demonstrated sound psychometric properties (Brandon & Baker, 1991; Buckley et al., 2005; Downey & Kilbey, 1995). In the present investigation, the negative reinforcement/negative affect reduction subscale (SCQ-NR; e.g., “Smoking helps me calm down when I feel nervous”) was used as a criterion variable; internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s α = .933).

Procedure

Adult daily smokers were recruited from the community (via flyers, newspaper ads, radio announcements) to participate in a large randomized controlled dual-site clinical trial examining the efficacy of two smoking cessation interventions. Individuals responding to study advertisements were scheduled for an in-person, baseline assessment to evaluate study inclusion and exclusion criteria. After providing written informed consent, participants were interviewed using the SCID-I/NP and completed a computerized battery of self-report questionnaires. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each study site; all study procedures and treatment of human subjects were conducted in compliance with ethical standards of the American Psychological Association. The current study is based on secondary analyses of baseline (pre-treatment) data for a sub-set of the sample, which was on the basis of available data on all studied variables.

Data Analytic Strategy

Analyses were conducted in PASW Statistics 21.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics). First, zero-order correlations among the predictor (ASI-III), proposed mediator (AIS), and all criterion variables were examined. Outcome measures were selected in order to capture a range of tobacco related behavioral and cognitive domains related to smoking and smoking cessation: BCS-Total [Y1], number of previous quit attempts [Y2], severity of problematic symptoms reported in past quit attempts [Y3], and SCQ-NR [Y4]. Next, a series of mediator models were conducted to examine the impact of AIS as a mediator of the relation between ASI-III and the criterion outcomes (i.e., a total of 4 models were conducted). Gender, level of nicotine dependence (FTND), alcohol use (AUDIT), cannabis use status (per MSHQ), negative affectivity (PANAS-NA), and tobacco-related medical problems were included as covariates in the models. The mediation analyses were conducted using PROCESS, a conditional process modeling program that utilizes an ordinary least squares-based path analytical framework to test for both direct and indirect effects (Hayes, 2013). All relative indirect effects were subjected to follow-up bootstrap analyses with 10,000 samples to estimate a 95-percentile confidence interval (CI; as recommended by Hayes, 2009; Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008).

Results

Participants primarily identified as White (85.8%) while fewer identified as African-American (8.3%), Hispanic (2.4%), Asian (1.1%), and other (2.4%). Participants were well educated with 70.4% indicating that they completed at least part of college. In terms of relationship status, 44.0% reported marital status as never married, 33.3% as married/cohabitating, 20.9% as divorced/separated, and 1.9% as widowed.

The average daily smoking rate of this sample was 16.6 (SD = 9.92), and on average, participants reported daily smoking for 18.3 years (SD = 13.35). Slightly more than one-quarter of the participants (29.6%) reported a tobacco-related illness (heart problems, hypertension, respiratory disease, and/or asthma). Participants reported an average of 3.4 previous “serious” quit attempts (SD = 2.42; observed range 0–15); a small percentage of the sample reported no previous quit attempts (7.1%; n = 33).

Of the sample, 44.4% met criteria for at least one current (past year) psychological disorder which included: social anxiety disorder (10.3%), generalized anxiety disorder (4.9%), alcohol use disorder (4.6%), major depressive disorder (4.3%), specific phobia (4.0%), posttraumatic stress disorder (3.0%), cannabis use disorder (3.0%), panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (2.1%), dysthymia (1.9%), anxiety disorder not otherwise specified (1.4%), adjustment disorder (1.3%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (1.1%), bipolar disorder (0.4%), cocaine dependence (0.4%), poly-substance use disorder (0.4%), agoraphobia without panic disorder (0.2%), and depressive disorder not otherwise specified (0.2%).

The ASI-III total score was significantly and positively associated with nicotine dependence, alcohol use, negative affectivity, smoking inflexibility, severity of problems experienced while quitting, and negative reinforcement smoking expectancies (see Table 1). The mediator (AIS) also was significantly (and positively) related to nicotine dependence, negative affectivity, and all criterion variables; correlations were small to moderate in strength. Additionally, male gender was significantly associated with higher AUDIT scores, whereas female gender was related to higher scores on the PANAS-NA, AIS, BCS, severity of problems experienced while quitting, and SCQ-NR.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations for study variables (n = 466).

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (% Female)a | 1 | −.010 | −.104* | −.061 | .000 | .135** | .077 | .183** | .223** | .011 | .284** | .174** |

| 2. FTNDa | 1 | −.106* | −.066 | −.023 | .051 | .134** | .254** | .194** | .022 | .178** | .173** | |

| 3. AUDIT totala | 1 | .193** | −.117* | .243** | .212** | .037 | .090 | −.047 | .046 | .166** | ||

| 4. Cannabis Use (% Y)a | 1 | .040 | .075 | .059 | −.066 | −.002 | −.163** | −.109* | .004 | |||

| 5. Medical Problemsa | 1 | .011 | .015 | .058 | .006 | .031 | .016 | −.091* | ||||

| 6. PANAS-NAa | 1 | .629** | .244** | .371** | −.014 | .369** | .374** | |||||

| 7. ASI-IIIb | 1 | .251** | .319** | .028 | .378** | .294** | ||||||

| 8. AISc | 1 | .582** | .105* | .409** | .468** | |||||||

| 9. BCSd | 1 | .020 | .511** | .515** | ||||||||

| 10. # Quit Attemptsd | 1 | .259** | .002 | |||||||||

| 11. Quit Problemsd | 1 | .424** | ||||||||||

| 12. SCQ-NRd | 1 | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mean (or n) | 226 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 260 | 0.4 | 19.1 | 15.2 | 45.0 | 24.9 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 5.7 |

| SD (or %) | 48.5 | 2.29 | 6.02 | 55.8 | .62 | 7.06 | 12.29 | 10.73 | 11.04 | 2.42 | .67 | 1.78 |

Note:

p < .05;

p < .01;

Covariates;

Predictor;

Mediator;

Criterion Variables

Gender = % listed are females (coded 0 =male; 1 = female); FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence – total score; AUDIT Total = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; Cannabis Use = Past 30 days cannabis use status per the Marijuana Smoking History Questionnaire; Medical Problems = Tobacco-related medical problems as indicated by the a medical history form; PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale – Negative Affect subscale; ASI-III = Anxiety Sensitivity Index-III; AIS = Acceptance and Inflexibility Scale – Total score; BCS = Barriers to Cessation Scale – Total score; # Quit Attempts = Number of lifetime serious quit attempts per the Smoking History Questionnaire; Quit Problems = Mean severity rating of problems experienced while quitting per the Smoking History Questionnaire; SCQ-NR = Smoking Consequences Questionnaire – Negative Reinforcement subscale. Columns numbers 1 – 12 correspond to the variables numbers in the far left column.

Mediational Models

Next, four regression models were constructed in order to tests each criterion variable. Regression results for paths a, b, c, and c′ are presented in Table 2, which correspond to each of the four models. The estimates of the indirect effects were the paths tested for mediation, which also are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Regression results for the mediation models.

| Y | Model | b | SE | t | p | CI (lower) | CI (upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ASI →→ AIS (a) | .104 | .049 | 2.131 | .034 | .008 | .120 |

| AIS →→ BCS (b) | .503 | .040 | 12.467 | <.0001 | .424 | .583 | |

| ASI →→ BCS (c′) | .048 | .042 | 1.126 | .261 | −.036 | .131 | |

| ASI →→ BCS (c) | .100 | .049 | 2.052 | .041 | .004 | .196 | |

| ASI →→ AIS 33 BCS (a*b) | .052 | .023 | .008 | .098 | |||

|

| |||||||

| 2 | AIS →→ #QUIT (b) | .023 | .011 | 2.048 | .041 | .001 | .045 |

| ASI →→ #QUIT (c′) | .011 | .012 | .883 | .378 | −.013 | .034 | |

| ASI →→ #QUIT (c) | .013 | .012 | 1.084 | .279 | −.010 | .036 | |

| ASI →→ AIS →→ #QUIT (a*b) | .002 | .001 | .001 | .007 | |||

|

| |||||||

| 3 | AIS →→ PROB (b) | .018 | .003 | 6.986 | <.0001 | .013 | .023 |

| ASI →→ PROB (c′) | .013 | .003 | 4.712 | <.0001 | .007 | .018 | |

| ASI →→ PROB (c) | .014 | .003 | 4. 993 | <.0001 | .009 | .020 | |

| ASI →→ AIS →→ PROB (a*b) | .001 | .001 | −.001 | .003 | |||

|

| |||||||

| 4 | AIS →→ SCQ-NR (b) | .063 | .007 | 8.928 | <.0001 | .049 | .076 |

| ASI →→ SCQ-NR (c′) | .003 | .007 | .344 | .731 | −.012 | .017 | |

| ASI →→ SCQ-NR (c) | .009 | .008 | 1.140 | .255 | −.007 | .025 | |

| ASI →→ AIS →→ SCQ-NR (a*b) | .007 | .003 | .001 | .012 | |||

Note. Path a is equal across all model; therefore, it presented only in the model with Y1 to avoid redundancies. n = 466 in models of Y1,2,4; n = 433 in model of Y3 (i.e., those reporting ≥ 1 previous quit attempt). The standard error and 95% CI for a*b are obtained by bootstrapping with 10,000 re-samples. ASI (Anxiety sensitivity) is the independent variable (X), AIS (Smoking-related affective Inflexibility) is the mediator (M), and BCS (Barriers to Smoking Cessation total score; Y1), #QUIT (Number of previous quit attempts; Y2), PROB (Severity of quit problems experienced; Y3), and SCQ-NR (Negative reinforcement expectancies; Y4), are the outcomes. CI (lower) = lower bound of a 95% confidence interval; CI (upper) = upperbound; →→=affects.

In terms of BCS-Total (Y1), the total effect model was significant (R2y1,x = .209, df = 7, 458, F = 17.333, p < .0001; path c), as was the full model with the mediator (R2M,x = .410, df = 8,457, F = 39.708, p < .0001). In the full model, female gender was significantly predictive of higher scores on the BCS (b = 2.372, p = .0001), as were higher levels of negative affectivity (per the PANAS-NA; b = .303, p = .0001). The direct effect (path c′) of ASI-III on BCS, after controlling for the mediator, was non-significant. Regarding the test of the indirect (mediational) effect, higher levels of anxiety sensitivity were predictive of greater perceived barriers to smoking cessation indirectly through greater levels of AIS (effect a*b).

In regard to number of prior serious quit attempts (Y2), both the total effect model (R2y2,x = .031, df = 7, 458, F = 2.071, p < .045) and the full model with mediators accounted for significant variance (R2M,x = .040, df = 8, 457, F = 2.349, p = .018). In the full model, cannabis use in the past 30 days was associated with fewer quit attempts (b = −.757, p = .001). After controlling for the mediator, the direct effect of ASI-III on previous quit attempts remained significant. Regarding the test of the indirect effect, higher levels of anxiety sensitivity were predictive of more self-reported prior quit attempts indirectly through greater levels of AIS.

In terms of severity of problematic symptoms reported in past quit attempts (Y3), these analyses were conducted on the sample of participants reporting ≥ 1 previous quit attempts (n = 433). The total effects model accounted for significant variance (R2y3,x = .3304, df = 7,425, F = 26.449, p < .0001). The full model with the mediator also predicted significant variance in quit problem severity (R2M,x = .376, df = 8, 424, F = 31.872, p < .0001). Female gender (b = .263, p < .0001) and higher levels of negative affectivity (b = .015, p = .002) were predictive of greater severity of quit). The direct effect of ASI-III on severity of problematic symptoms reported in past quit attempts remained significant after controlling for the mediator. To test mediation, the indirect effect was estimated; results were non-significant for the mediational effect of AIS.

With regard to negative reinforcement smoking expectancies (SCQ-NR; Y4), the total effects model accounted for significant variance (R2y4,x = .202, df = 7, 458, F = 16.599, p < .0001). The full model with the mediator predicted significant variance in SCQ-NR (R2M,x = .321, df = 8, 457, F = 26.985, p < .0001). In the full model, female gender (b = .059, p < .0001), higher levels of negative affectivity (b = .297, p = .038), higher AUDIT scores (b = .028, p = .023), and fewer tobacco-related physical problems (b = −.299, p = .008) were predictive of higher scores on the SCQ-NR. The direct effect of ASI-III on SCQ-NR, controlling for the mediator, was non-significant. The indirect effect was estimated and reveled that higher levels of anxiety sensitivity were predictive of higher SCQ-NR scores indirectly through greater levels of AIS.

Model Specificity

Lastly, despite the theoretically-driven model guiding the research questions, as a method of further strengthening the interpretation of results, alternative mediation models were tested. Here, proposed predictor (anxiety sensitivity; ASI-III) and mediator (AIS) variables were reversed for each of the four models tested previously (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). Tests of the indirect effects in these reversed mediation models were estimated based on 10,000 bootstrapped re-samples. Results of the reversed mediation models were non-significant for perceived barriers for quitting (b = .007, CI95% = −.001, .024), number of previous quit attempts (b = .001, CI95% = −.001, .005), and expectancies about smoking-based affect reduction (b = .001, CI95% = −.001, .003). However, there was a significant AIS to ASI-III to problematic symptoms reported in past quit attempts pathway (b = .002, CI95% = .001, .023).

Post-Hoc Analyses

Based on the significant the significant main effects of gender, a series of four post-hoc moderated meditational models were conducted in order to examine the extent to which gender moderated the effect of anxiety sensitivity on AIS, and the direct effect of anxiety sensitivity on the smoking variables (Yi). Tests of the conditional and overall indirect effects were estimated based on 10,000 bootstrapped re-samples. Results revealed a non-significant overall indirect effect of gender*AIS in terms of anxiety sensitivity on BCS-Total (b = −.042, CI95% = −.122, .034), number of quit attempts (b = −.002, CI95% = −.008, .001), severity of quit problems among those with = previous quit attempt ([n = 332]; b = −.001, CI95% = −.004, .002), or negative affect-reduction smoking expectancies (b = −.005, CI95% = −.012, .004). That is, gender did not moderate the meditational effect of AIS in the observed models. However, there was a significant conditional direct effect for female gender and anxiety sensitivity on quit history and severity of quit problems, such that females high in anxiety sensitivity reported significantly more lifetime smoking quit attempts (b = .036, SE = .015, t = 2.322, p = .021) and a greater severity of quit problems (b = .014, SE = .005, t = 2.971, p = .0001). There were not significant conditional effects for male gender and anxiety sensitivity on any of the criterion variables.

Discussion

Consistent with expectation, the effect of anxiety sensitivity on perceived barriers for quitting, number of previous quit attempts and expectancies about smoking-based affect reduction was significantly mediated by the tendency to respond with inflexibility/avoidance in the presence of aversive smoking-related thoughts, feelings, or internal sensations (AIS). Notably, these observed effects were evident above and beyond the variance accounted for by level of nicotine dependence, alcohol and cannabis use, negative affectivity, and tobacco-related medical problems. Thus, the observed effects and incremental in nature and cannot be attributed to these factors. Interestingly, the findings were not significant for the severity of problematic symptoms reported in past quit attempts, which suggests that AIS may, at least partially, explain the relations between anxiety sensitivity and some, but not all, smoking processes among treatment-seeking smokers. Specifically, individuals with higher levels of anxiety sensitivity may tend to be more inflexible in their smoking behavior during emotionally salient contexts which, in turn, may theoretically contribute to more mood-management smoking cognitions, quit attempts, and perceived challenges in quitting smoking, but not symptom severity during past quit attempts.

Although the cross-sectional nature of our research design does not permit explication of temporal ordering of the observed associations, we attempted to improve confidence in the observations by evaluating alternative explanatory models, in which we reversed the predictor and mediator variable for each of the four criterion variables. The results of these models in combination with those yielded by the main analyses are consistent with the hypothesis that anxiety sensitivity may contribute to AIS, which in turn, is related to a variety of smoking processes. Interestingly, these findings also suggested that, at least with regard to the severity of problematic symptoms experienced in past quit attempts, the relation between anxiety sensitivity and AIS may be reciprocal. To more fully explore the nature of the relation among these variables over time, future prospective modeling of the temporal ordering of anxiety sensitivity and AIS in terms of smoking processes is warranted.

In post hoc tests, females compared to males reported more robust associations with the smoking criterion variables, although this did not moderate the indirect effects of AIS in terms of anxiety sensitivity and smoking processes. However, consistent with previous research, females high in anxiety sensitivity reported a greater number of previously lifetime quit attempts and more severe problems while quitting. These findings are in accord with past work that suggests female smokers may have more vulnerability to negative affect during periods of smoking deprivation (Pang & Leventhal, 2013) and poorer cessation outcomes (Wetter et al., 1999). Most research suggests females compared to males report more and intense fears (Bekker, 1996). Additionally, women generally report greater overall levels of anxiety sensitivity than men (Stewart, Conrod, Gignac, & Phil, 1998). As such, gender may serve an important role in the aforementioned anxiety sensitivity-AIS smoking model. Namely, females compared to males may be more apt to endorse greater anxiety sensitivity and thereby be more apt to inflexibly seek out smoking to escape, avoid, or reduce distressing states, resulting in more problems in quitting.

It is noteworthy to highlight two additional observations. First, anxiety sensitivity and AIS were inter-related, but distinct constructs (these two constructs shared 6% of variance with one another; see correlations in Table 1). Indeed, this observation lends empirical support to the construct validity of these two affective vulnerability processes. Second, AIS also was related, but empirically distinct, from the criterion variables (range of shared variance: 0%–29%). These data add to the emerging scientific literature suggesting inflexibility/avoidance in the presence of distressing smoking-related thoughts, feelings and internal sensations is a unique and clinically-relevant construct (AIS; Gifford et al., 2004).

The findings from the investigation may serve to conceptually inform the development of specialized intervention strategies for smokers with elevated risk for anxiety and depressive psychopathology (e.g., smokers high in anxiety sensitivity). Existing anxiety sensitivity reduction programs for smoking cessation, albeit still in developmental phases, have provided evidence of the feasibility and merit of incorporating tailored cognitive-behavioral skills that specifically address affective vulnerabilities (e.g., interoceptive exposure, psychoeducation) into smoking cessation programs (Zvolensky et al., 2008). Consistent with such work, the present findings suggest that it may be advisable to understand and clinically address anxiety sensitivity to enhance psychological flexibility related to smoking in order to address maladaptive smoking cognitions and facilitate more successful cessation. Indeed, acceptance-based techniques (e.g., experiential awareness, openness, willingness, mindfulness, cognitive diffusion) have been shown to reliably reduce AIS (Bricker et al., 2010). Thus, such skills may important to integrate into existing cognitive-behavioral anxiety sensitivity-reduction smoking cessation programs or other psychosocial intervention programs for anxiety/mood disordered smokers. For example, it may be useful to encourage smokers to work toward accepting distressing smoking-related sensations, thoughts, and feeling states (e.g., nicotine withdrawal, negative mood) when making a quit attempt, and to provide specific training in such tactics prior to quitting to solidify a minimum level of competence in such skill sets (e.g., exposure to nicotine withdrawal and acceptance of the discomfort that accompanies it).

There are a number of interpretive caveats to the present study that warrant further consideration. First, given the cross-sectional nature of these data, it is unknown whether anxiety sensitivity is causally related to greater AIS, or the criterion smoking processes. The present mediation tests here were solely based on a theoretical framework and did not allow for testing of temporal sequencing. Based upon the present results, future prospective studies are necessary to determine the directional effects of these relations. Second, our sample consisted of community-recruited, treatment-seeking daily cigarette smokers with moderate levels of nicotine dependence. Future studies may benefit by sampling from lighter and heavier smoking populations to ensure the generalizability of the results to the general smoking population. It also is noteworthy that the FTND internal consistency was relatively low, an issue often apparent with this measure (Korte, Capron, Zvolensky, & Schmidt, 2013). Yet, Cronbach alpha values are fairly sensitive to the number of items in each scale and it is not uncommon to find lower Cronbach values with shorter scales (e.g., scales with < 10 items; DeVellis, 2003). Third, the current study relied solely on self-report measures to assess the examined predictor, mediator, and outcome variables. Future research could benefit by utilizing multi-method approaches and minimizing the role of method variance in the observed relations. For example, experimental provocation procedures such as emotion elicitation via biological challenge could be useful in examining the present relations in response to aversive interoceptive states elicited in real time. Fourth, the sample was largely comprised of a relatively homogenous group of treatment-seeking smokers. To rule out a selection bias and increase the generalizability of these findings, it will be important for future studies to recruit a more ethnically/racially diverse sample of smokers.

Overall, the present study serves as an initial investigation into the nature of the association between anxiety sensitivity, AIS, and a relatively wide range of smoking processes among adult treatment-seeking smokers. Based upon these data, future work is needed to explore the extent to which AIS accounts for relations between anxiety sensitivity and other smoking processes (e.g., withdrawal, cessation outcome) and to further clarify theoretical models of emotional vulnerability and smoking, and to inform clinical assessment and intervention development/refinement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health grant awarded to Drs. Michael J. Zvolensky and Norman B. Schmidt (R01-MH076629). Ms. Farris is supported by a cancer prevention fellowship through the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center funded by the National Cancer Institute (R25T-CA057730), and a pre-doctoral National Research Service Award from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (F31-DA035564).

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors contributed significantly to the development and writing of this manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

No authors have any conflicts of interests or financial disclosures to report. Please note that the content presented does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, and that the funding sources had no other role other than financial support.

References

- Assayag Y, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ, Steeves D, Stewart SS. Nature and role of change in anxiety sensitivity during NRT-aided cognitive-behavioral smoking cessation treatment. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2012;41(1):51–62. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.632437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care, Revision, WHO Document No. WHO/PSA/92.4. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Battista SR, Stewart SH, Fulton HG, Steeves D, Darredeau C, Gavric D. A further investigation of the relations of anxiety sensitivity to smoking motives. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:1402–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekker MHJ. Agoraphobia and gender: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 1996;16:129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ. An evaluation of the nature of marijuana use and its motives among young adult active users. The American Journal on Addictions. 2009;18(5):409–416. doi: 10.3109/10550490903077705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Baker TB. The smoking consequences questionnaire: The subjective expected utility of smoking in college students. Psychological Assessment. 1991;3:484–491. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.3.3.484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Mann SL, Marek PM, Liu J, Peterson AV. Telephone-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy for adult smoking cessation: A feasibility study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(4):454–458. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Strong DR, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Carpenter L, Niaura R, Price LH. A prospective examination of distress tolerance and early smoking lapse in adult self-quitters. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:493–502. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW, Ramsey SE. Anxiety sensitivity: Relationship to negative affect smoking and smoking cessation in smokers with past major depressive disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:887–899. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:180–185. doi: 10.1037//0021-843X.111.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Palm KM, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Gifford EV. Distress tolerance treatment for early-lapse smokers: Rationale, program description, and preliminary findings. Behavior Modification. 2008;32(3):302–332. doi: 10.1177/0145445507309024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Reed KMP, Bloom EL, Minami H, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Hayes SC. Development and preliminary randomized controlled trial of a distress tolerance treatment for smokers with a history of early lapse. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt093. Advance online access. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TC, Kamholz BW, Mozley SL, Gulliver SB, Holohan DR, Helstrom AW, Kassel JD. A psychometric evaluation of the Smoking Consequences Questionnaire--Adult in smokers with psychiatric conditions. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2005;7(5):739–745. doi: 10.1080/14622200500259788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comeau N, Stewart SH, Loba P. The relations of trait anxiety, anxiety sensitivity, and sensation seeking to adolescents’ motivations for alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:803–825. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis RF. Scale development: Theory and applications. 2. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Downey KK, Kilbey MM. Relationship between nicotine and alcohol expectancies and substance dependence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1995;3(2):174–182. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.3.2.174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korte KJ, Capron DW, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. The Fagerström scales: Does altering the scoring enhance the psychometric properties? Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:1757–1763. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evatt DP, Kassel JD. Smoking, arousal, and affect: The role of anxiety sensitivity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24(1):114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition (SCIDI/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Antonuccio DO, Piasecki MM, Rasmussen-Hall ML, Palm KM. Acceptance-based treatment for smoking cessation. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35(4):689–705. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV, Lillis J. Avoidance and inflexibility as a common clinical pathway in obesity and smoking treatment. Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14(7):992–996. doi: 10.1177/1359105309342304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV, Ritsher JB, McKellar JD, Moos RH. Acceptance and relationship context: a model of substance use disorder treatment outcome. Addiction. 2006;101(8):1167–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P, Belcher M, Stapleton J. Breath-holding endurance as a predictor of success in smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors. 1987;12:285–288. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76(4):408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guildford Press; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB. Predictors of panic attacks in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:207–214. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-López M, Luciano M, Bricker JB, Roales-Nieto JG, Montesinos F. Acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation: A preliminary study of its effectiveness in comparison with cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(4):723–730. doi: 10.1037/a0017632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Farris SG, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety sensitivity and cognitive-based smoking processes: Testing the mediating role of emotion dysregulation among treatment-seeking daily smokers. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2012;31:143–157. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2012.665695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Farris SG, Schmidt NB, Smits JAJ, Zvolensky MJ. Panic attack history and anxiety sensitivity in relation to cognitive-based smoking processes among treatment-seeking daily smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15(1):1–10. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Stewart S, Rosenfield D, Steeves D, Zvolensky MJ. Prospective evaluation of the effects of anxiety sensitivity and state anxiety in predicting acute nicotine withdrawal symptoms during smoking cessation. Psychology Of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(2):289–297. doi: 10.1037/a0024133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu W, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-Month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langdon KJ, Leventhal AM, Stewart S, Rosenfield D, Steeves D, Zvolensky MJ. Anhedonia and anxiety sensitivity: Prospective relationships to nicotine withdrawal symptoms during smoking cessation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74(3):469–478. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd J, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein D, McCormick D, Bor D. Smoking and mental illness. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, Bernstein A. Anxiety sensitivity and smoking motives and outcome expectancies among adult daily smokers: Replication and extension. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(5):985–994. doi: 10.1080/14622200802097555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macnee CL, Talsma A. Development and testing of the barriers to cessation scale. Nursing Research. 1995;44(4):214–219. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maller RG, Reiss S. Anxiety sensitivity in 1984 and panic attacks in 1987. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1992;6:241–247. doi: 10.1016/0887-6185(92)90036-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GN, Miles JV, Stewart SH. Anxiety sensitivity and PTSD symptom severity are reciprocally related: Evidence from a longitudinal study of physical trauma survivors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(1):143–150. doi: 10.1037/a0018009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe RE, Chudzik SM, Antony MM, Young L, Swinson RP, Zolvensky MJ. Smoking behaviors across anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2004;18(1):7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity and panic disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:938–946. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullane JC, Stewart SH, Rhyno E, Steeves D, Watt M, Eisner A. Anxiety sensitivity and difficulties with smoking cessation. In: Columbus F, editor. Advances in Psychology Research. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pang RD, Leventhal AM. Sex differences in negative affect and lapse behavior during acute tobacco abstinence: A laboratory study. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;21(4):269–276. doi: 10.1037/a0033429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC. Does cigarette smoking cause stress? American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):817–820. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Giedgowd GE, Conklin CA, Sayette MA. Differences in negative mood-induced smoking reinforcement due to distress tolerance, anxiety sensitivity, and depression history. Psychopharmacology. 2010;210:25–34. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1811-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau C, Carton S, Lutzke M, Flessland K, Pomerleau O. Reliability of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire and the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence. Addictive Behaviors. 1994;19:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Medoro L. Fear of physical sensations and trait anxiety as mediators of the response to hyperventilation in nonclinical subjects. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103(4):693–699. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.103.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky M, McNally RJ. Anxiety, sensitivity, anxiety frequency, and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Lerew DR, Jackson RJ. Prospective evaluation of anxiety sensitivity in the pathogenesis of panic: Replication and extension. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:532–537. doi: 10.1037//0021-843X.108.3.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ, Maner JK. Anxiety sensitivity: Prospective prediction of panic attacks and Axis I pathology. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40(8):691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Taylor S, Baker JM. Gender differences in dimensions of anxiety sensitivity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1997;11:179–200. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. Anxiety sensitivity and its implications for understanding and treating PTSD. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2003;17(2):179–186. doi: 10.1891/jcop.17.2.179.57431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ, Deacon B, Heimberg RG, Ledley DR, Cardenas SJ. Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: Development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(2):176–188. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trafton JA, Gifford EV. Behavioral reactivity and addiction: The adaptation of behavioral response to reward opportunities. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2008;20(1):23–35. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.20.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trafton JA, Gifford EV. Biological bases of distress tolerance. In: Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, Vujanovic AA, editors. Distress tolerance: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 80–102. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;47:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RJ, Hajek P, Belcher M. Severity of withdrawal symptoms as a predictor of outcome of an attempt to quit smoking. Psychological Medicine. 1989;19(4):981–985. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700005705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, Kenford SL, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Baker TB. Gender differences in smoking cessation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:555–562. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M, Krajisnik A, Truong L, Lisha NE, Trujillo M, Greenberg JB, Leventhal AM. Anxiety sensitivity as a predictor of acute subjective effects of smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15(6):1084–1090. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Cigarette smoking and panic psychopathology. Current Directions In Psychological Science. 2005;14(6):301–305. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Yartz AR, Gregor K, Gonzalez A, Bernstein A. Interoceptive exposure-based cessation intervention for smokers high in anxiety sensitivity: A case series. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;22(4):346–365. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.22.4.346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]