Summary

Previous work linked nitric oxide (NO) signaling to histone deacetelyases (HDACs) in the control of tissue homeostasis, and suggested that deregulation of this signaling contributes to human diseases. In the previous issue, Liao et al. (2014) show that coordinated NO signaling and histone acetylation are required for propercranial neural crest development and craniofacial morphogenesis and suggest that alterations of NO/acetylation network can contribute to the pathogenesis of craniofacial malformations.

In order to get a full picture of the interplay between genetic and epigenetic factors in the molecular pathogenesis of congenital disorders, we need to improve our understanding of how developmental cues are converted into epigenetic modifications that control the expression of specific sub-sets of genes during lineage determination. Indeed, genetic mutations that compromise the integrity of histone-modifying complexes involved in epigenetic regulation have been associated with malformations, and might account for differences in disease penetrance and severity caused by changes in environmental exposure. Craniofacial formation provides a notable example of a developmental process that is tightly regulated at the epigenetic level, and gene mutations altering the activity of enzymes that regulate histone acetylation, metylation and sumoylation result in orofacial malformations (Alkuraya et al. 2006; Fischer et al. 2006; Qi et al. 2010; Kraft et al. 2011; Delaurier et al., 2012).

In the previous issue of Chemistry & Biology, Liao et al. (2014), use a chemical genetics screen in zebrafish embryos to discover molecular determinants of craniofacial development during embryogenesis. Using both gene (crestin) expression-based and phenotypic screening they identified a nitric oxidase synthase inhibitor (TRIM) that impairs cranial neural crest (CNC) development, by inhibiting migration of CNC cells and their differentiation into the chondrocyte lineage. This phenotype can be rescued by implementing histone acetylation, through either over-expression of the acetyltransferase (HAT)kat6a or pharmacological blockade of HDACs by Trichostatin A (TSA), indicating a functional relationship between NO signaling and histone acetylation for proper CNC development and craniofacial morphogenesis (Figure 1). Cell lineage tracing and gene expression analysis support the conclusion that NO is an upstream signal that controls the balance between HATs and HDAC during CNC cell lineage determination; however, the authors could not conclusively work out the functional and biochemical details underlying NO-mediated control of histone acetylation. The finding that nuclei of TRIM-treated embryos show decreased (by half) levels of acetylated histone H4 are clearly in support of a physiological inhibitory action of NO on histone acetylation. Still, it remains unclear whether NO signaling directly targets histone-modifying complexes to regulate gene expression in CNC cells.

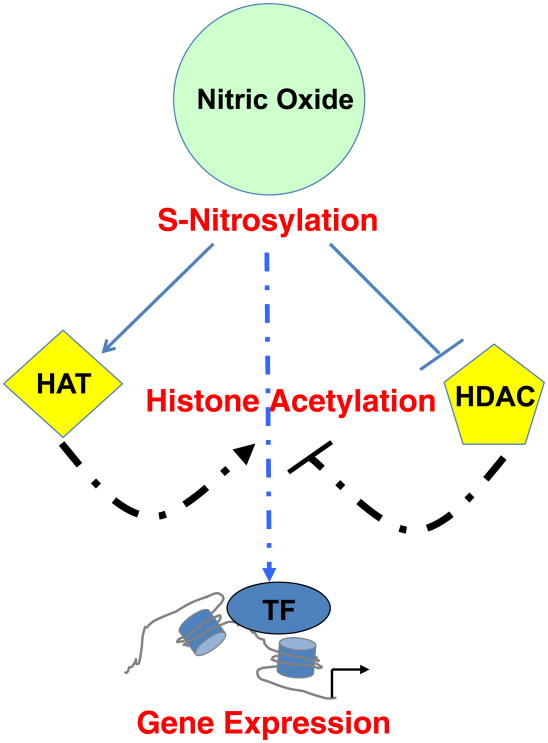

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of NO-mediated control of gene expression.

Nitric oxide (NO) signaling can influence gene expression of specific cell types, such as cranial neural crest (CNC) cells during development, by S-nitrosylation of enzymes that promote (histone acetyltransferases – HAT) or inhibit (histone deacetylases - HDAC) histone acetylation or by direct targeting histones or transcription factors (TF).

Previous work has revealed that S-nitrosylation of HDACs is a post-transcriptional modification, which couples NO production to chromatin remodeling and regulation of gene expression in adult tissues (Colussi et al. 2008; Nott et al., 2008). NO is a second messenger signaling molecule generated by NO synthase (NOS) family of enzymes that regulates many developmental processes (Moncada and Higgs, 1993), via cysteine nitrosylation (S-nitrosylation) of proteins and transcription factors (Hess and Stamler, 2012). S-nitrosylation of HDAC2 provided a seminal evidence in support of a direct NO-regulated chromatin remodeling in neuronal development (Nott et al., 2008) and skeletal muscle homeostasis (Colussi et al. 2008). Interestingly, deregulated NO signaling to HDAC2 has been reported in muscles the Mdxmouse model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), due to the absence of nNOS-interacting dystrophin domain, and ultimately leading to a constitutive activation of HDAC2 (Colussi et al. 2008). The beneficial effect of HDAC inhibitors and NO donors in Mdxmice (Minetti et al., 2006, Brunelli et al., 2007) suggests that alteration of NO-HDAC signaling contributes to DMD pathogenesis and indicates the potential therapeutic relevance of the pharmacological control of NO-mediated nitrosylation of HDAC.

Liao et al. show that TRIM-induced phenotype is more effectively rescued by complementary NO production than by gain-of-function approaches that implement histone acetylation (i.e. HAT overexpression or HDAC inhibition). This evidence, while positioning NO upstream of HAT/HDAC, also indicates alternative ways by which NO can regulate gene expression in CNC cells – e.g. by direct S-nitrosylation of histone or transcription factors. However, the authors failed to detect general alterations in S-nitrosylation of total proteins upon TRIM treatment, by using biotin switch assay. It is possible that more sophisticated biochemical approaches are required to capture S-nitrosylation of potential epigenetic effector(s) of NO-mediated regulation of gene expression and lineage determination of CNC cells.

Developmental processes are often resumed during adult life and their alterations might contribute to the pathogenesis and progression of human diseases. As aberrant protein S-nitrosylation is implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases (Nakamura et al. 2013), further elucidation of the molecular and biochemical relationship between NO, acetylation and gene expression in specific cell types of interest, such as tissue progenitors during embryo development and post-natal tissue homeostasis or repair, might uncover common pathological events between developmental and adult disorders.

Overall, the study of Kong and coworkers (Liao et al., 2014) emphasizes the power of the chemical genetic screening in the zebrafish embryo as a tool to identify novel pathways governing specific developmental stages and potential targets of pharmacological approaches aimed at preventing genetic malformations and countering the progression of certain adult diseases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- Alkuraya, et al. Science. 2006;313(5794):1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1128406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:264–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608277104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colussi, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(2008):19183–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805514105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaurier, et al. BMC Dev Biol. 2012;(2012):16. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, et al. Human Mol Genet. 2006;15:581–587. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, et al. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3479–3491. doi: 10.1172/JCI43428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess, Stamler J Biol Chem. 2012;287(2012):4411–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.285742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao, et al. Chemistry & Biology. 2014;21:xxx–xxx. [Google Scholar]

- Minetti, et al. Nat Med. 2006;12(2006):1147–50. doi: 10.1038/nm1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada, Higgs N Engl J Med. 1993;329(1993):2002–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, et al. Neuron. 2013;78(4):596–614. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nott, et al. Nature. 2008;455(2008):411–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi, et al. Nature. 2010;466(2010):503–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]