Abstract

Background

Parent knowledge influences decisions regarding medical care for their children.

Methods

Parents of pediatric primary care patients aged 9-14 years, irrespective of height, participated in open focus groups (OFG). Moderators asked, “How do people find out about growth hormone (GH)?” Because many parents cited the Internet, the top 10 results from the Google searches, growth hormone children and parents of children who take growth hormone, were examined as representative. Three investigators independently performed content analysis, then reached consensus. Results were tabulated via summary statistics.

Results

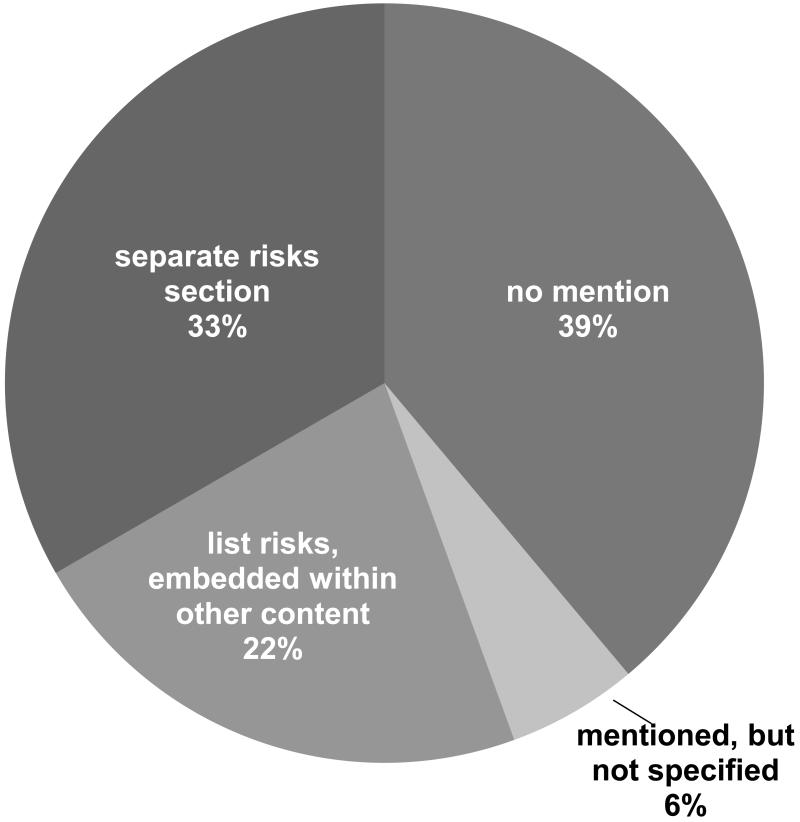

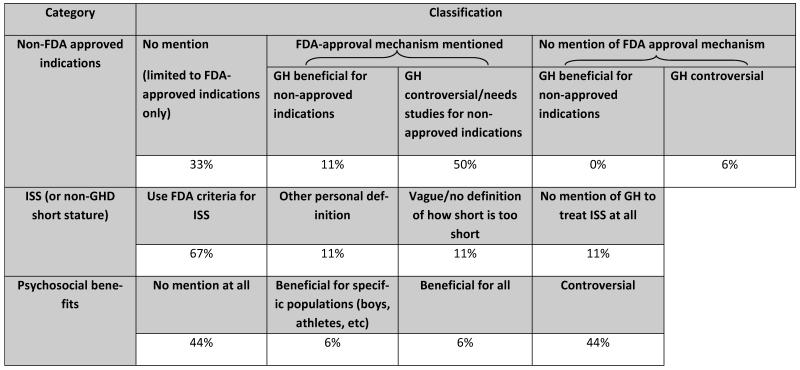

Eighteen websites were reviewed, most with the purpose of education (56%) and many funded by commercial sources (44%). GH treatment information varied, with 33% of sites containing content only about U.S Food and Drug Administration-approved indications. Fifty-six percent of sites included information about psychosocial benefits from treatment, 44% acknowledging them as controversial. Although important to OFG participants, risks and costs were each omitted from 39% of websites.

Conclusion

Parents often turn to the Internet for GH-related information for their children, though its content may be incomplete and/or biased. Clinicians may want to provide parents with tools for critically evaluating Internet-based information, a list of pre-reviewed websites, or their own educational materials.

Keywords: Growth Hormone, Internet, Risk, Benefit, Parents

Introduction

Short stature is a common concern in pediatrics, as growth is an important indicator of child health [1]. Concerns about a child’s poor growth may be raised by their parents, their primary care provider (PCP), or both. Many factors, including a child’s physical health, quality of life and psychological well being, contribute to a parent’s decision to seek evaluation and treatment for a child’s short stature [2-5]. Ultimately, the PCP must identify children with abnormal growth patterns and decide whether to investigate further with diagnostic tests and/or referral to a specialist. Parental concern and psychosocial issues can influence the medical decision-making process, irrespective of objective measures of the child’s growth. Family concern increased both PCP referrals to specialists [6] and the prescribing of growth hormone (GH) by endocrinologists [7, 8]. Parent perceptions of the benefits of GH treatment also affect their acceptance of physician treatment recommendations [9].

Due to the influence of parental concern on the medical decision-making process, we sought to understand how parents learn about GH treatment and the information that is readily available.

Methods

Open focus groups

The study was granted exemption by the institutional review board of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. To explore parent knowledge about short stature and its treatment, 13 open focus groups (OFG) were held with a total of 71 (40 African American, 31 Caucasian) parents of children aged 9-14 years, randomly selected from six primary care pediatric practices affiliated with a tertiary care pediatric hospital. They were stratified by race, but child height was not a factor in participant selection. Two trained researchers moderated each OFG and prompted with open-ended questions, including “How do people find out about GH?” OFG sessions were audio-recorded, transcribed and then analyzed to identify themes (NVivo 8, 2008 QSR International, Australia).

Website content analysis

On November 8, 2011, two searches were conducted (Google, Mountain View, CA) using the phrases, growth hormone children and parents of children who take growth hormone. The resulting top ten sites from each phrase were examined as representative. Sponsored sites - those that paid a premium to be listed on the results page of a search engine - were excluded from analysis. These sites were considered advertisements, which may have the greatest potential for bias and skew results when included in summary statistics. Consumers may already be thinking about caveat emptor when looking at these sites, as opposed to sites “natu-rally” listed by the Google search, potentially rendering them less critical readers of the non-sponsored sites.

Each search was replicated monthly (12/8/2011 and 1/6/2012) to evaluate temporal consistency among the results. The first ten sites from all six searches were tabulated and duplicates deleted. Three members of the research team independently scored the resulting 18 unique websites (Appendix A) using a novel coding rubric (supplement). Because people browse the Internet expeditiously, we focused on content found within three clicks of the homepage of each site. Further, only static text (not reader comments) on the webpage was reviewed. Each rater chose the single best classification for each of twelve categories. After all websites were scored, discrepancies were discussed and resolved as a group to reach consensus. Results were analyzed via descriptive statistics (Microsoft 2007, Redmond, WA).

Results

Open focus groups

Parents in five of the 13 OFG (38%) cited the Internet as a resource to learn about GH treatment, while participants in 10 OFG (77%) identified physicians as a source. Magazines, television and movies (31%), or friends and family members (54%) were also cited.

Participant comments clustered into three themes: the Internet was a ready source of GH-related information, Internet-based information could be useful before and after medical evaluation, and relying on Internet-based information warranted caution. For example, one OFG participant stated, “The Internet. You can get anything off the Internet.” Another specified, “Internet, it’s the Google,” to which others agreed. Some participants, possibly experienced with GH treatment or evaluation, reported seeking information on the Internet before or after medical evaluation. One mother explained, “Just been working with his endocrinologist and just trying to get more inform— and I read up a lot, you know, I got on the Internet, I read about it.” A father said, “If a doctor tells you, oh, this would benefit your son, but he hasn’t given you a script, you go on the Internet, bam, this is the name of it, this is how we get it.” However, some participants acknowledged negative aspects of Internet information. Two participants commented, “You know, sometimes the Internet’s a really dangerous thing” and “…unfortunately you can get way too many things over the Internet.”

Website content analysis

Google search (11/8/11) of growth hormone children yielded about 6,620,000 results and parents of children who take growth hormone yielded about 5,530,000 results. By 12/8/11 those search term results increased to 11,700,000 and 6,120,000, respectively. A third search (1/6/12) yielded 8,740,000 and 6,750,000 results, respectively. However, the top 10 sites for each search term remained consistent.

Website characteristics

Website purpose and sponsor were analyzed to understand the aims of the site and who is responsible for webpage maintenance. Educational sites were identified as those trying to provide information, such as The MAG-IC Foundation and Wikipedia. Advocacy sites aimed at reversing discrimination against short people, such as Short Persons Support. Most of the websites (56%) aimed at educating their reader, 33% presented news stories, 6% were pharmaceutical based product information and 6% were advocacy. Of the sites, 44% had commercial funding (supported by advertisements or sales), such as WebMD or pharmaceutical companies. Foundations sponsored 33%, 22% belonged to hospitals or academic institutions, and none were funded by government or parent groups. While commercial sources like pharmaceutical companies often provide financial support to foundations, hospitals or academic institutions, the relative contribution of this indirect funding to the website authors is not transparent or quantifiable and so categorization was limited to the direct funding source only. Thirty-nine percent referred to GH in the generic, while 33% named three or more commercial brands of GH, 11% named two brands and 17% cited only one brand name. This included mention of a pharmaceutical company or specific GH product.

Audience and potential population for GH treatment were also analyzed to determine the site’s focus. Two thirds of the websites dealt with pediatric GH use, while the remainder discussed both pediatric and adult indications or GH in general. None focused solely on GH use in adults, as expected given that both search phrases contained the term children. Content of 61% of the websites referred to GH treatment in the broadest context, while 11% were limited to GH deficiency (GHD) and other diseases, and 28% to idiopathic short stature (ISS) specifically. None of the websites included illicit uses of GH treatment, such as sports performance enhancement or antiaging. Accessibility to potential readers was evaluated along two parameters. Readability divided content into above or at/below a seventh grade reading level, based on the density of polysyllabic words, sentence structure and length, and the amount of medical jargon. Complexity referred to the site’s structure, with “simple” describing straightforward websites and “complex” sites containing multiple sections. Half of the websites were considered simple with content at or below seventh grade reading level, and 33% simple with a higher reading level. Only 17% of sites were complex, 11% at the lower reading level and 6% above.

Content about benefits and risks of GH treatment

In OFG, parents reported they would consider benefits and risks when deciding whether to seek treatment for a short child. Website content analysis regarding benefits of GH treatment is summarized in Table 1, and risks in figure 1. Current controversies surrounding potential benefits of GH treatment include off-label use for non-approved indications, height enhancement in healthy short children solely for psychosocial benefits (such as career and dating success as an adult, or a decrease in emotional distress, bullying and teasing as a child [10]), and promoting expanded use by relaxing the terms of the FDA-approved definition of ISS (height more than 2.25 standard deviations below the mean [1.2nd percentile] for age and gender, growth velocity that will not lead to a normal adult height, and identifiable causes of growth failure have been ruled out [11]). For example, 11% of websites gave a vague or no definition of how short is too short, while another 11% used their own definition of ISS, such as “The cutoff point to be considered eligible for treatment is under age 14” [12]. Similar to over-stated benefits, under-reported risks can bias parents towards wanting GH treatment for their child. For example, one website [13] stated, “Growth hormone does not have any significant side effects when used as a replacement therapy for growth hormone inadequacy or deficiency,” and three sites [14- 16] identified the most common side effects as “mild, including ear infections and joint and muscle pain.”

TABLE 1.

Content analysis of potential benefits of GH treatment. Results show percent of websites classified for each of the three categories.

|

Abbreviations: GH, growth hormone; GHD, growth hormone deficiency; ISS, idiopathic short stature; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration

FIGURE 1.

Website content about potential risks of GH treatment.

One website directly stated GH “does not have any significant side effects.”

Content about acquiring GH

Parents may also seek information related to getting and paying for GH treatment. All of the reviewed websites recommended seeking the opinion of a medical professional to obtain GH treatment, while only half cited an endocrinologist specifically. Specific information about cost varied, with half providing an annual cost of GH treatment between $10,000 and $30,000. Thirty-nine percent did not discuss cost. Cost was mentioned, without stating who was responsible for payment, on 22% of sites. Twenty-two percent acknowledged expensive out of pocket costs, even with insurance, while 11% reassured that insurance covered GH, with no information about personal costs. Assistance with payment, such as coupons, co-pay support or other promotions, was offered on 6% of the websites.

Discussion

In summary, we found that parents are likely to talk with their medical professional and/or turn to the Internet to obtain information if concerned about their children’s stature. This was true for parents with limited GH awareness and for those who had already sought the assistance of a medical professional but still had some unanswered questions. Our content analysis found that pertinent websites are more likely to be commercially funded and although most are aimed at educating the public, important information such as possible side effects and costs of treatment may be minimized or lacking.

Internet use has been increasing, as a convenient, anonymous and cost-efficient method of obtaining information, and health information specifically. In 2010, 74% of U.S. adults used the Internet [17] and in 2011, 56% of Europeans reported using the Internet daily or almost daily [18]; 80% of the former and 54% of the latter looked online for health information [17, 18]. Patients commonly search the Internet to investigate drug side effects or complications of a medical therapy [19]. Reasons cited in a children’s hospital study included wanting to know more (97%), reducing anxiety (75%), because more information was available than had been provided by the doctor (53%), or the doctor had not been able to adequately answer all of their questions (53%) [20]. Parents used Google as their search engine (75%), with their children’s condition (90%) or symptoms (21%) as keyword(s) [21].

The Internet can empower patients and their families to proactively work with their PCP to lead a healthier lifestyle and detect potential problems earlier [22]. However, as our OFG participants cautioned, there are also pitfalls to relying on the Internet for health information. Internet content is often unregulated and for many, the amount of information can be overwhelming, with good quality information difficult to find [23]. Of the 500 sites searched using Google for five common pediatric questions, 39% gave correct information, 11% were incorrect and 49% failed to answer the question [24]. Likewise, only one link out of five using 14 of the most popular search engines led to a website with relevant information on four common diseases [25].

Consistent with comments from parents in our OFG, studies have shown that parents are still, most often, relying on a medical professional for health information regarding their children [26, 27]. What information patients receive from medical professionals is unknown. The attitudes and beliefs of physicians themselves about short stature and its toll on emotional well-being have been shown to influence the referral patterns of PCPs [6], the prescribing practices of endocrinologists [28], and the approach to shared decision-making about GH as an elective therapy [29]. Health information retrieved from the Internet may influence the patient-family/physician shared decision-making process [30, 31].

One limitation to the current study is that OFG are non-quantifiable, providing data on only the number of groups with pertinent comments, but not the relative proportions of people who would seek Internet information. Insofar as the focus groups were open, we did not ask about the specific search engines or search terms the participants would use. Therefore, we selected general search terms informed by our own search habits, that we believed most likely would be used by parents and hence yield representative results. This study reviewed only the first 10 websites for each search term over the course of three months, thereby limiting the number of sites reviewed. Because parents are often under time constraints and most try to browse expeditiously, we believed that parents/users would not read much beyond these results. While observer bias is always possible, it was minimized by several factors. We created categories based on information from OFG that parents use when deciding to seek evaluation and treatment for a child’s stature. The coding rubric was created and finalized prior to any scoring and performed independently by three investigators of different professional backgrounds.

We learned that parents often rely on the Internet for information about GH treatment for their children. As we found, Internet content may be biased, minimizing the potential side effects and costs of treatment. Website content may also be incomplete, lacking important information critical to a parent’s decision-making process. Clinician awareness of the information available to parents regarding GH treatment is important to patient care. To ensure that parents receive accurate information, clinicians may want to prepare a list of pre-reviewed websites, create their own educational materials or provide tools for critically evaluating Internet-based information, such as the “Trust It or Trash It” website (http://www.trustortrash.org/) [32].

Additional Contributions/Acknowledgments

We want to thank the network of primary care clinicians, their patients and families for their contribution to this project and clinical research facilitated through the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia PeRC. In particular, we’d like to thank the following practices for allowing us to recruit parents for the focus groups: Chestnut Hill, Coatesville, Haverford, Roxborough, and South Philadelphia. We also want to thank our OFG moderators, Charles Adams, Stephen Oliver and Denise Outlaw.

Funding/Support

This work was supported by grant R01 HD057037 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (A.G.). We are grateful to the Pediatric Research Consortium (PeRC) at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, funded in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Appendix A

List of resulting 18 websites analyzed.

http://www.magicfoundation.org/www/docs/108/growth_hormone_deficiency_in_children

http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/05/03/helping-short-kids-grow-up/

http://kidshealth.org/teen/diseases_conditions/growth/growth_hormone.html

http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2003/06/11/earlyshow/health/main558240.shtml

http://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/human-growth-hormone-and-the-measure-of-man

http://www.shortsupport.org/Research/Papers/growthHormonmeTreatment.html

http://kidshealth.org/parent/medical/endocrine/growth_disorder.html

http://children.webmd.com/news/20081106/growth-hormone-therapy-ups-kids-height

http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2003/11/18/60II/main584265.shtml

http://www.emedicinehealth.com/growth_hormone_deficiency_in_children/article_em.htm

Contributor Information

Pamela Cousounis, Division of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Philadelphia, PA.

Terri H. Lipman, Division of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Kenneth Ginsburg, The Craig-Dalsimer Division of Adolescent Medicine, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, PA.

Adda Grimberg, Diagnostic and Research Growth Center; Division of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, PA.

References

- 1.Grimberg A, Lifshitz F. Worrisome Growth. In: Lifshitz F, editor. Pediatric Endocrinology. 5th edition Informa Health Care; New York: 2007. pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bullinger M, Koltowska-Haggstrom M, Sandberg D, Chaplin J, Wollmann H, Noeker M, Brutt AL. Health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with growth hormone deficiency or idiopathic short staturepart 2: available results and future directions. Horm Res. 2009;72:74–81. doi: 10.1159/000232159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandberg DE, Voss LD. The psychosocial consequences of short stature: a review of the evidence. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;16:449–463. doi: 10.1053/beem.2002.0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandberg DE, Bukowski WM, Fung CM, Noll RB. Height and social adjustment: are extremes cause for concern and action? Pediatrics. 2004;114:744–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1169-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JM, Appugliese D, Coleman SM, Kaciroti N, Corwyn RF, Bradley RH, Sandberg DE, Lumeng JC. Short stature in population-based cohort: social, emotional, and behavioral functioning. Pediatrics. 2009;124:903–910. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuttler L, Marinova D, Mercer MB, Connors A, Meehan R, Silvers JB. Patient, physician, and consumer drivers: referrals for short stature and access to specialty drugs. Med Care. 2009;47:858–65. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819e1f04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardin DS, Woo J, Butsch R, Huett B. Current Prescribing practices and opinions about growth hormone therapy: results of a nationwide survey of paediatric endocrinologists. Clinical Endocrinology. 2007;66:85–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuttler L, Silvers JB, Singh J, Marrero U, Finkelstein B, Tannin G, Neuhauser D. Short Stature and Growth Hormone Therapy. JAMA. 1996;276:531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haverkamp F, Gasteyger C. A review of biopsychosocial strategies to prevent and overcome early-recognized poor adherence in growth hormone therapy of children. J Med Econ. 2011;14:448–457. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2011.590829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldsmith SB. Short Persons Support. 2000 8 Nov. 2011 < http://shortsupport.org/>.

- 11.Orloff DG. Approval Letter: Humatrope (somatropin [rDNA origin] for injection) 5, 6, 12, 24 mg vials and cartridges. Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation Research Web Site; 2003. Available at: < http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2003/19640se1-033ltr.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen Jamie. ABC News. ABC News Network; Nov 8, 2011. Should Short Kids Use Growth Hormones? 17 June. Web. < http://abcnews.go.com/Health/story?id=116731&page=1#.UNHTeOTAe8B>. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magic Foundation for Children’s Growth: Human (HGH) Growth Hormone Deficiency in Children. Site. 2011 Nov 8; N.p., n.d. < http://www.magicfoundation.org/www/docs/108/growth_hormone_deficiency_in_children>.

- 14.Gunn K. Health Psychology Home Page. Human Growth Hormone for Children. 2011 Nov 8; 2 Dec. 2002. Web. < http://healthpsych.psy.vanderbilt.edu/HGH_kids.htm>.

- 15.Leung R. CBSNews. CBS Interactive; Nov 8, 2011. Kids’ Hormones: A Growth Industry. 11 Feb. 2009. Web. < http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2003/11/18/60II/main584265.shtml>. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox D. The New Atlantis » Human Growth Hormone and the Measure of Man. The New Atlantis » Human Growth Hormone and the Measure of Man. 2012 Nov 8 8;Oct 8 8; Fall 2004-Winter 2005. Web. 2011. < http://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/human-growth-hormone-and-the-measure-of-man>.17. “ Fox S. ”Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project.“ The Social Life of Health Information, 2011. N.p., 12 May 2011. Web. < http://pewinternet.org/reports/2011/social-life-of-health-info>. [PubMed]

- 17.Seybert H. [Accessed on December 5, 2012];Internet use in households and by individuals in 2011. Eurostat statistics in Focus 66/2011. 2011

- 18.Wainstein BK, Sterling-Levis K, Baker SA, Taitz J, Brydon M. Use of the internet by parents of paediatric patients. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42:528–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sim NZ, Kitteringham L, Spitz L, Pierro A, Kiely E, Drake D, Curry D. Information on the World Wide Web – how useful is it for parents? J Paediatric Surgery. 2007;42:305–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diaz JA, Griffith RA, James NJ, Reinert SE, Friedmann PD, Moulton AW. Patients’ use of the internet for medical information. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:180–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morahan-Martin JM. How internet users find, evaluate, and use online health information: a cross-cultural review. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2004;7:497–510. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benigeri M, Pluye P. Shortcomings of health information on the Internet. Health Promotion International. 2003;18:381–386. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dag409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scullard P, Peacock C, Davies P. Googling children’s health: reliability of medical advice on the internet. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:580–582. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.168856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berland GK, Elliott MN, Morales LS, Algazy JI, Kravitz RL, Broder MS, Kanouse DE, Munoz JA, Puyol J, Lara M, Watkins KE, Yang H, McGlynn EA. Health information on the internet: accessibility, quality, and readability in English and Spanish. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:2612–2621. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.20.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoo K, Bolt P, Babl FE, Jury S, Goldman RD. Health information seeking by parents in the Internet age. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008;44:419–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2008.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Dongen N, Kaptein AA. Parents’ views on growth hormone treatment for their children: psychosocial issues. Patient Preference and Adherence. 2012;6:547–553. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S33157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silvers JB, Marinova D, Mercer MB, Connors A, Cuttler L. A national study of physician recommendations to initiate and discontinue growth hormone for short stature. Pediatrics. 2010;126:468–476. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laventhal NT, Shuchman M, Sandberg DE. Warnings about Warnings: Weighing Risk and Benefit When Information Is in a State of Flux. Hormone Research in Paediatrics. 2013;79:4–8. doi: 10.1159/000346381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fox S, Rainie L. Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. The Online Health Care Revolution. 2012 Oct 19; N.p., 26 Nov. 2000. Web. < http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2000/The-Online-Health-Care-Revolution.aspx>. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semere W, Karamanoukian HL, Levitt M, Edwards T, Murero M, D’Ancona G, Donias HW, Glick PL. A pediatric surgery study: parent usage of the internet for medical information. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:560–4. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2003.50122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trust It or Trash It? Trust It or Trash It? Genetic Alliance. 2013 Feb 28; 13 Apr. 2011. Web. < http://trustortrash.org/>. [PubMed]