Abstract

Background

As a measure of quality, ambulatory surgery centers have begun reporting rates of hospital transfer at discharge. However, this may underestimate patient’s acute care needs after care. We conducted this study to determine rates and evaluate variation in hospital transfer and hospital-based, acute care within 7 days among patients discharged from ambulatory surgery centers.

Methods

Using data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, we identified adult patients who underwent a medical or surgical procedure between July 2008 and September 2009 at ambulatory surgery centers in California, Florida, and Nebraska. The primary outcomes were hospital transfer at the time of discharge and hospital-based, acute care (emergency department visits or hospital admissions) within 7-days expressed as the rate per 1,000 discharges. At the ambulatory surgery center level, rates were adjusted for age, sex, and procedure-mix.

Results

We studied 3,821,670 patients treated at 1,295 ambulatory surgery centers. At discharge, the hospital transfer rate was 1.1/1,000 discharges (95% CI, 1.1–1.1). Among patients discharged home, the hospital-based, acute care rate was 31.8/1,000 discharges (95% CI, 31.6–32.0). Across ambulatory surgery centers, there was little variation in adjusted hospital transfer rates (median=1.0/1,000 discharges [25th–75th percentile=1.0–2.0]), while substantial variation existed in adjusted hospital-based, acute care rates (28.0/1,000 [21.0–39.0]).

Conclusions

Among adult patients undergoing ambulatory surgery center care, hospital transfer at discharge is a rare event. In contrast, the hospital-based, acute care rate is nearly 30-fold higher, varies across centers, and may be a more meaningful measure for discriminating quality.

Introduction

Ambulatory surgery centers have become the preferred setting for providing low-risk medical and surgical procedures, such as colonoscopy and glaucoma surgery, in the United States.1 The proportion of all such procedures performed in this setting has increased 3-fold over the last two decades, from 20% to 60% of all medical or surgical procedures.1–2 In parallel with ambulatory surgery center expansion, there has been a growing focus on ensuring patients receive high-quality care in this setting.3–4 To this end, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has adopted five measures of quality which ambulatory surgery centers were required to begin reporting to CMS as of October 2012 and on which reimbursement will be based beginning in 2014. These measures include patient burns, patient falls, prophylactic antibiotic timing, wrong site surgery, and hospital transfer at the time of discharge.5–7

The rate of hospital transfer at the time of discharge is intended to be a marker of complications resulting from care.7 However, not all complications may be immediately evident and result in a hospital transfer. Treatment-related complications8–10 and symptoms11 may develop over the hours or days following discharge and require subsequent emergency department visits or hospital admissions, termed hospital-based, acute care.12–13 For example, patients may present to the emergency department for perforation after colonoscopy; urinary retention subsequent to hemorrhoidectomy; or severe nausea following anesthesia.8–10 By not concurrently measuring these post-discharge events, adverse outcomes related to treatment could be missed, the resultant measure of ambulatory surgery center quality misrepresented, and, when linked to payment, perverse incentives established to err on the side of a home discharge in lieu of hospital transfer.

While prior studies suggest that hospital transfer rates are approximately 1 per 1,000 patients, little is known about how frequently patients require hospital-based, acute care after being discharge home.13–15 Similarly, it is unknown if either rate varies substantially across centers to allow for meaningful discrimination between high and low performing centers. Therefore, we conducted this study of ambulatory surgery centers in three geographically dispersed U.S. states to determine these rates; the most common diagnoses associated with these encounters; and whether they varied across centers. Because quality measures developed for the Medicare population are often adopted by other payers, we also evaluated these outcomes in an all-payer setting, and then specifically among those 65 years and older. By doing so, findings from this study may help inform efforts aimed at measuring the quality of health care provided in ambulatory surgery centers across payers and provide an early evaluation of the proposed measure.

Methods

We used state-level, administrative data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP).16 Specifically, data were drawn from the 2008–2009 California (CA), Florida (FL), and Nebraska (NE) ambulatory surgery,17 inpatient,18 and emergency department19 databases. These states were selected for analysis because their databases contain unique variables which allow patients to be followed over time and across the ambulatory surgery, inpatient, and emergency department settings; their geographic diversity; and the quality of their data. For CA and FL, these data are a census of discharges from free-standing and hospital-affiliated ambulatory surgery centers. For NE, the ambulatory surgery data is exclusively from hospital-affiliated ambulatory surgery centers. All three state inpatient databases represent a census of discharges from all acute care, non-federal, community hospitals, whereas the emergency department database is a census of emergency department encounters which did not result in hospital admission. In 2009, these databases included information on over 5 million ambulatory surgery center, 6 million inpatient, and 16 million emergency department discharges. Information for each patient discharge includes up to 21 Current Procedural Terminology or International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) procedure codes, 15 diagnostic ICD-9-CM codes, and information about patient demographics, anticipated payer, and discharge disposition.

Patient selection

From the ambulatory surgery databases, we identified all discharges for medical and surgical procedures between July 1, 2008 and September 30, 2009 among state residents who were at least 18 years of age and had valid encrypted person-level identifiers (N = 5,298,025). Next, we sequentially excluded discharges where the disposition was listed as missing (N = 3,363), death (N = 163), or left against medical advice (N = 1,093). After exclusions, 5,293,406 ambulatory center surgery discharges remained among 3,822,064 unique patients. For patients that had more than 1 discharge, we randomly selected one for study inclusion. Finally, to avoid including rare or miscoded cases, we excluded patients who underwent a procedure performed fewer than 50 times among the three states (N = 394). Patients were then grouped according to their index procedure defined as the primary CPT code listed for the ambulatory surgery center encounter. Because CPT codes are so numerous, we aggregated individual CPT codes into broad categories of similar procedure using HCUP’s Clinical Classifications Software for Services and Procedures.20

Main Outcome Variables

Our two primary outcomes were rates of hospital transfer and hospital-based, acute care within 7 days of discharge. A hospital transfer was defined as any discharge from an ambulatory surgery center where the disposition was listed as “transfer to an acute care facility.” This variable is predefined in the database. Among patients who were not immediately transferred, hospital-based, acute care was defined as any hospital admission or emergency department visit not resulting in admission (i.e., “treat-and-release” visit) within 7 days of discharge. These encounters were identified from corresponding state-level inpatient and emergency department databases thereby allowing encounters at institutions other than the discharging facility to be captured. As our objective was to identify hospital-based, acute care encounters that were not pre-planned or part of a patient treatment course, we did not include hospital admissions that were directly admitted (i.e., without a prior emergency department visit) if the primary diagnosis was maintenance radiation or chemotherapy, rehabilitation services, cancer, or normal obstetrical delivery (see Appendix 1 for specific ICD-9-CM coding). All other hospital admissions which originated in the emergency department were included, regardless of the primary diagnosis.

For all hospital-based, acute care encounters, we recorded the primary diagnostic categories associated with the encounter based on AHRQ’s clinical classification groupings of diagnostic ICD-9-CM codes21 and whether the encounter occurred after-hours when defined as weekends or weekdays between the hours of 1700 and 0900 (only Florida and Nebraska databases include these time data).

Descriptive variables

Several patient characteristics were obtained for both descriptive and risk-standardization purposes, including patient age, sex, race and ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic, Other, and Missing), primary payer (Medicare, Medicaid, Private, Other), median household income based on the patient’s home zip code (quartiles), and the first listed procedure associated with the discharge when grouped by AHRQ’s classification of Current Procedural Terminology coding.22 We assessed comorbidity according to the enhanced-Elixhauser algorithm described by Quan et. al.23–24 which identifies 31 chronic medical conditions. A patient was considered to have a condition if it was a listed diagnosis during the initial ambulatory surgery center discharge or at any inpatient or emergency department discharge in the previous 6 months.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the observed rate of hospital transfer and hospital-based, acute care within 7 days at the ambulatory surgery center level. This was done by dividing the number of events (numerator) by the number of patients at-risk for the outcome (denominator) expressed as the rate per 1,000 discharges. Descriptive statistics were used to estimate average rates with 95 percent confidence intervals (CI) for the overall sample and the 20 most frequently performed procedures and surgeries.

In order to compare rates across centers, we calculated the age, sex, and procedure-adjusted hospital transfer and hospital-based, acute care rates for each ambulatory surgery center using 2-level, hierarchical generalized linear models using methods similar to existing Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services measures.25–26 One model was constructed for each outcome specifying a binomial distribution using the GLIMMIX procedure.27 The first level included variables for patient age, sex, and procedure-type (a 21-level categorical variable specifying the 20 most common procedures by volume or “other”), whereas the second level included an ambulatory surgery center random intercept. For each ambulatory surgery center, the rates were calculated as the ratio of the number of “predicted” outcomes (obtained from a model applying the hospital-specific effect) to the number of “expected” outcomes (obtained from a model applying the average effect among hospitals), multiplied by the unadjusted rate for the entire sample. For this analysis, we limited the sample to ambulatory surgery centers reporting at least 43 discharges (>5th percentile by volume in the overall sample) meeting the above criteria during the study period to avoid unstable parameter estimates. We also conducted an age-stratified analysis of outcomes across centers with aged 65-years as the cut-off. In this case, rates were adjusted for sex and procedure-mix only and limited to centers with at least 23 cases (>5th percentile by volume in the sample at least 65 years of age).

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Because this study used publicly available data that does not include patient identifiers, it was considered exempt from review by the Yale University Human Investigations Committee and the Wright State University Institutional Review Board.

Results

There were 3,821,670 unique patients treated at 1,295 ambulatory surgery centers in these three States that met our study inclusion criteria. Most patients were female (54.6%), white (63.0%), had private forms of insurance (50.9%), and a low overall prevalence of co-morbid medical conditions (Table 1). Colonoscopy accounted for 27.2% of all primary procedures performed (N=1,040,530), followed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (10.3%; N=394,300), lens and cataract procedures (9.7%; N=368,867), and pain management services (i.e., insertion of catheters or spinal stimulators or injections into the spinal canal; 4.7%; N=179,546). Collectively, the 20 most common procedures by volume accounted for 74.8% of all ambulatory surgery center discharges.

Table 1.

Description of the sample

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Overall | 3,821,670 | 100.00 |

| Age group, years | ||

| 18 – 29 | 215,785 | 5.7 |

| 30 – 39 | 297,568 | 7.8 |

| 40 – 49 | 551,840 | 14.4 |

| 50 – 59 | 854,537 | 22.4 |

| 60 – 69 | 822,933 | 21.5 |

| 70 – 79 | 697,037 | 18.2 |

| 80 or older | 381,970 | 10.0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1,602,926 | 41.9 |

| Female | 2,091,393 | 54.7 |

| Missing | 127,351 | 3.3 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| White | 2,404,876 | 62.9 |

| Black | 220,279 | 5.8 |

| Hispanic | 444,313 | 11.6 |

| Other | 227,721 | 6.0 |

| Missing | 524,481 | 13.7 |

| Primary payer | ||

| Medicare | 1,440,295 | 37.7 |

| Medicaid | 179,807 | 4.7 |

| Private | 1,943,188 | 50.9 |

| Other | 258,380 | 6.8 |

| Median household income based on patient’s home zipcode | ||

| $1 – $39,999 | 781,963 | 20.5 |

| $40,000 – $49,999 | 925,280 | 24.2 |

| $50,000 – $65,999 | 983,815 | 25.7 |

| $66,000 or greater | 1,063,858 | 27.8 |

| Missing | 66,754 | 1.8 |

| Elixhauser co-morbidity | ||

| No conditions | 2,368,251 | 62.0 |

| 1 – 2 conditions | 1,015,778 | 26.6 |

| 3– 4 condition | 292,877 | 7.7 |

| 5 or more conditions | 144,764 | 3.8 |

Immediate Transfer Rates

Among all ambulatory surgical center discharges, 4,219 (0.1%) patients required hospital transfer at the time of discharge for an overall observed hospital transfer rate of 1.1 (95% CI, 1.1–1.1) per 1,000 discharges. However, there was notable variation in hospital transfer rates across individual medical and surgical procedures. For example, the observed hospital transfer rates ranged from 0.1 (95% CI, 0.1–0.3) per 1,000 for breast biopsies to 19.1 (95% CI, 18.3–20.0) per 1,000 for diagnostic cardiac catheterizations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Observed rates of hospital transfer and hospital-based, acute care within 7-days of discharge from an ambulatory surgery center (rates per 1,000 discharges)

| Total sample1

|

Medicare-aged subgroup1

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index procedure3 | N | % | Hospital transfer | Hospital-based, acute care2 | Hospital transfer | Hospital-based, acute care2 |

| Overall | 3,821,670 | 100.0 | 1.1 (1.1–1.1) | 31.8 (31.6–32.0) | 1.3 (1.3–1.4) | 30.6 (30.3–30.9) |

| Colonoscopy and biopsy | 1,040,530 | 27.2 | 0.4 (0.3–0.4) | 13.2 (13.0–13.4) | 0.6 (0.5–0.6) | 15.0 (14.6–15.4) |

| Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, biopsy | 394,300 | 10.3 | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) | 29.0 (28.4–29.4) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 27.9 (27.1–28.8) |

| Lens and cataract procedures | 368,867 | 9.7 | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 9.7 (9.4–10.0) | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 9.5 (9.2–9.9) |

| Insertion of catheter or spinal stimulator and injection into spinal canal | 179,546 | 4.7 | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | 19.8 (19.2–20.5) | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | 18.8 (17.8–19.9) |

| Diagnostic cardiac catheterization, coronary arteriography | 107,253 | 2.8 | 19.1 (18.3–20.0) | 81.9 (80.2–83.7) | 18.1 (17.0–19.2) | 77.1 (74.8–79.5) |

| Excision of semilunar cartilage of knee | 107,247 | 2.8 | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | 18.2 (17.4–19.0) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | 19.1 (17.4–21.0) |

| Inguinal and femoral hernia repair | 72,398 | 1.9 | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) | 42.1 (40.6–43.6) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 57.9 (55.0–60.9) |

| Excision of skin lesion | 71,410 | 1.9 | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | 21.8 (20.7–22.9) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 24.9 (23.0–27.1) |

| Cholecystectomy and common duct exploration | 70,325 | 1.8 | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 63.4 (61.6–65.3) | 1.5 (1.0–2.4) | 67.1 (62.6–71.9) |

| Lumpectomy, quadrantectomy of breast | 52,353 | 1.4 | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 15.9 (14.8–17.0) | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) | 17.0 (15.0–19.3) |

| Other vascular catheterization, not heart | 50,062 | 1.3 | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) | 95.6 (92.9–98.3) | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) | 94.0 (90.3–97.8) |

| Decompression peripheral nerve | 47,523 | 1.2 | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | 16.3 (15.2–17.5) | 0.3 (0.1–0.8) | 17.5 (15.6–19.7) |

| Other excision of cervix and uterus | 46,931 | 1.2 | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 21.7 (20.4–23.1) | 0.0 (0) | 25.0 (16.5–38.0) |

| Other hernia repair | 40,613 | 1.1 | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 43.3 (41.3–45.4) | 1.5 (0.9–2.7) | 52.0 (47.3–57.1) |

| Breast biopsy and other diagnostic procedures on breast | 39,268 | 1.0 | 0.1 (0.1–0.3) | 10.3 (9.4–11.4) | 0.0 (0) | 10.9 (9.0–13.2) |

| Arthroplasty other than hip or knee | 39,079 | 1.0 | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 27.3 (25.7–29.0) | 1.6 (0.9–2.6) | 37.1 (33.3–41.3) |

| Bunionectomy or repair of toe deformities | 37,151 | 1.0 | 1.6 (1.3–2.1) | 16.2 (14.9–17.5) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 16.8 (14.6–19.4) |

| Extracorporeal lithotripsy, urinary | 32,459 | 0.8 | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 80.8 (77.8–84.0) | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 70.0 (64.6–75.9) |

| Endoscopy and endoscopic biopsy of the urinary tract | 31,301 | 0.8 | 0.6 (0.4–1.0) | 40.1 (37.9–42.3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 40.3 (37.5–43.3) |

| Insertion, revision, replacement, removal of cardiac pacemaker or cardioverter/defibrillator | 30,573 | 0.8 | 1.8 (1.4–2.3) | 45.0 (42.7–47.5) | 1.6 (1.1–2.1) | 43.9 (41.4–46.6) |

| All other | 962,481 | 25.2 | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 55.1 (54.7–55.6) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 56.0 (55.2–56.8) |

Rates expressed as events per 1,000 discharges with 95% confidence intervals

Excluding patients who were immediately transferred to an acute care facility

Index procedures are defined according to the Clinical Classifications Software for Services and Procedures available through the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project which groups CPT/HCPCS coding into broad procedural groups. More information about this software, including specific CPT codes included in each category is available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs_svcsproc/ccssvcproc.jsp

Hospital-Based, Acute Care Rates

Among patients who were not immediately transferred to an acute care facility (N=3,817,451), there were 121,346 hospital-based, acute care encounters within 7 days of discharge for an overall observed rate of 31.8 (95% CI, 31.6–32.0) encounters per 1,000 discharges. Similar to hospital transfer rates, there was substantial variation in observed hospital-based, acute care rates across individual medical and surgical procedures. In this case, rates were relatively low at 9.7 (95% CI, 9.4–10.0) per 1,000 discharges for patients undergoing lens and cataract procedures, but were as high as 81.9 (95% CI, 80.2–83.7) per 1,000 discharges for patients undergoing diagnostic cardiac catheterization (Table 2). Across all medical and surgical procedures, approximately 30-fold more patients required hospital care within 7 days of discharge than required immediate transfer.

Description of hospital-based, acute care encounters

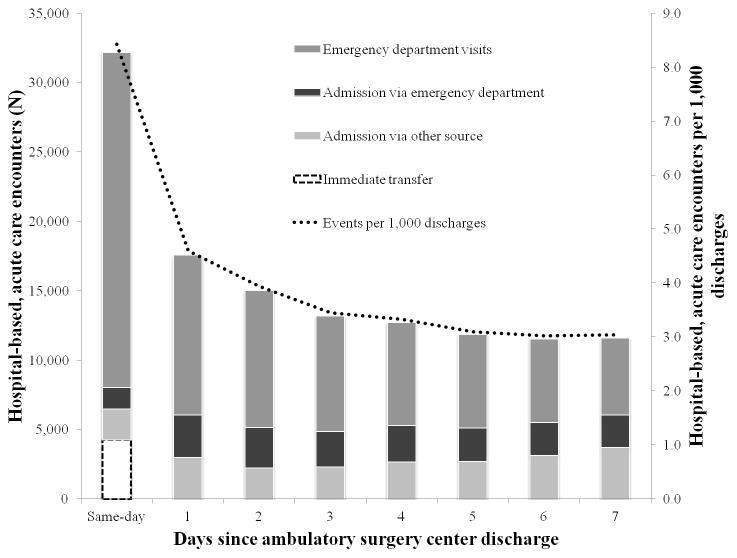

The majority of hospital-based, acute care encounters were emergency department visits (64.4%) that did not require subsequent admission. Temporally, the majority of these encounters occurred after normal office hours (64.5%) and nearly one-quarter took place on the same day as ambulatory surgery center discharge (23.0%). A smaller percentage of encounters occurred on each subsequent day following discharge (Figure 1). Patients tended to utilize acute care encounters for reasons that were related to their initial procedure. That is, the most common diagnoses associated with hospital-based, acute care encounters were complications of surgical procedures or medical care and symptoms of pain or discomfort. For instance, abdominal pain was common after colonoscopy and upper endoscopy, whereas patients undergoing placement of a cardiac pacemaker presented with complications of the device (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Observed hospital-based, acute care utilization within 7 days of ambulatory surgery center discharge among 3.8 million patients treated in California, Florida, and Nebraska between July 2008 and September 2009.

Table 3.

Diagnoses associated with hospital-based, acute care within 7-days of discharge from an ambulatory surgery center

| Index Procedure | Most common | 2nd | 3rd |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | Abdominal pain | Genitourinary symptoms and ill-defined conditions |

| Colonoscopy and biopsy | Abdominal pain | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | Other gastrointestinal disorders |

| Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, biopsy | Abdominal pain | Other injuries and conditions due to external cause | Nonspecific chest pain |

| Lens and cataract procedures | Cardiac dysrhythmias | Nonspecific chest pain | Superficial injury; contusion |

| Insertion of catheter or spinal stimulator and injection into spinal canal | Spondylosis; intervertebral disc disorders; other back problems | Other nervous system disorders | Nonspecific chest pain |

| Diagnostic cardiac catheterization, coronary arteriography | Coronary atherosclerosis and other heart disease | Nonspecific chest pain | Heart valve disorders |

| Excision of semilunar cartilage of knee | Other non-traumatic joint disorders | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | Other connective tissue disease |

| Inguinal and femoral hernia repair | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | Genitourinary symptoms and ill- defined conditions | Abdominal pain |

| Excision of skin lesion | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | Other aftercare | Skin and subcutaneous tissue infections |

| Cholecystectomy and common duct exploration | Abdominal pain | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | Biliary tract disease |

| Lumpectomy, quadrantectomy of breast | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | Other aftercare | Nonmalignant breast conditions |

| Other vascular catheterization, not heart | Complication of device; implant or graft | Nonspecific chest pain | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care |

| Decompression peripheral nerve | Other nervous system disorders | Other connective tissue disease | Other aftercare |

| Other excision of cervix and uterus | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | Other female genital disorders | Abdominal pain |

| Other hernia repair | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | Abdominal pain | Genitourinary symptoms and ill- defined conditions |

| Breast biopsy and other diagnostic procedures on breast | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | Nonmalignant breast conditions | Other nervous system disorders |

| Arthroplasty other than hip or knee | Other nervous system disorders | Other non-traumatic joint disorders | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care |

| Bunionectomy or repair of toe deformities | Other connective tissue disease | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | Other nervous system disorders |

| Extracorporeal lithotripsy, urinary | Calculus of urinary tract | Abdominal pain | Genitourinary symptoms and ill- defined conditions |

| Endoscopy and endoscopic biopsy of the urinary tract | Genitourinary symptoms and ill- defined conditions | Urinary tract infections | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care |

| Insertion, revision, replacement, removal of cardiac pacemaker or cardioverter/defibrillator | Complication of device; implant or graft | Cardiac dysrhythmias | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care |

| All other | Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | Genitourinary symptoms and ill- defined conditions | Complication of device; implant or graft |

The most common procedure was thoracentesis (95%)

Utilization in the Medicare-aged population

The most common procedures among adults 65 years or older (N=1,503,674) were colonoscopy (25.1%), lens and cataract procedures (20.0%), and upper endoscopy (10.1%). The observed rate of hospital transfer and hospital-based, acute care encounters within 7-days were similar to the overall population at 1.3 (1.3–1.4) and 30.6 (30.3–30.9) per 1,000 discharges, respectively (Table 2). The most common reasons for hospital-based, acute care within 7-days were complications of surgical procedure or medical care (e.g. bleeding, hematoma, or post-operative infections) and genitourinary symptoms (e.g. urinary retention).

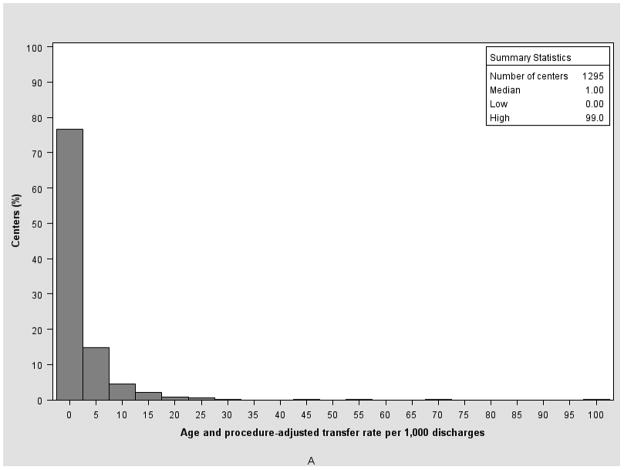

Variation of outcomes across ambulatory surgery centers

In the overall sample, there were 1,295 ambulatory surgery centers with at least 43 cases meeting our inclusion criteria (representing >5th percentile by volume in the overall sample). The median, adjusted risk standardized hospital transfer rate was 1.0 per 1,000 discharges (25th–75th percentile=1.0–2.0). In contrast, the median, adjusted risk standardized hospital-based, acute care encounter rate within 7-days post-discharge was 28.0 per 1,000 discharges (25th–75th percentile=21.0–39.0; Figure 2A–B). When limiting the sample to patients aged 65 years and older, 1,265 ambulatory surgery centers met the minimal volume threshold. Given the rarity of hospital transfer, we were unable to calculate an adjusted hospital transfer rate among this population. However, the median, risk standardized adjusted hospital-based acute care rate in 7-days was similar to the overall population: 27.2 per 1,000 (25th–75th percentile=22.7–34.8).

Figure 2.

Variation in risk standardized hospital transfer (A) and hospital-based, acute care in 7-day (B) rates across 1,295 centers where the y-axis represents the percentage of centers with a given outcome rate (x-axis).

Discussion

In this study examining acute care utilization after ambulatory surgery center discharge, we found that rates of hospital-based, acute care within 7 days were approximately 30-fold higher than rates of hospital transfer. Focusing solely on hospital transfers would have missed more than 95% of encounters requiring hospital-based acute care evaluations within 7 days of receiving care from ambulatory surgery centers and substantially underestimated post-ambulatory surgery center acute healthcare utilization. While this has implications for quality measurement and quality improvement efforts, it is critical from the patient perspective. Unlike hospital transfers where an adverse event was immediately recognized, patients who return for hospital-based, acute care represent a potentially missed or undiagnosed complication of care. The wide variation in the rate of these events across centers suggests progress could be made to improve the patient experience.

Performing medical and surgical procedures in ambulatory surgery centers has been beneficial for patients and the healthcare system. In addition to patients being able to return home more quickly, healthcare in this setting may be provided more efficiently and at a lower cost than the inpatient setting.28–29 However, these benefits could be negated if ambulatory surgery care leads to a heightened need for subsequent hospital-based, acute care following treatment. In the current study, we found return visits were most commonly attributable to procedure-related complications and post-procedure symptoms of pain and discomfort. Moreover, we found the majority of hospital-based, acute care encounters were emergency department visits that did not require subsequent hospital admission and occurred outside of normal office hours. If patients begin experiencing symptoms related to their care and are unprepared or unable to reach their usual healthcare provider, they may have few options other than seeking acute care. While all acute care needs may not be predictable or avoidable, efforts must be made to ensure better transitions in care. Improvements in care delivery could include appropriate patient selection, pre-procedure patient education, comprehensive discharge instructions, expansion of clinic hours and increased access to providers.

Our findings have important policy implications. First, hospital transfer rates do not vary across centers which may offer little in a patient’s or payer’s ability to determine which ambulatory surgery centers are providing “better” care. Rewarding or penalizing ambulatory care centers for performance on a metric limited to the hospital discharge could establish incentives whereby healthcare providers err on the side of discharging patients home rather than transferring to a higher level of care for further evaluation when needed. Additionally, if unadjusted rates are used to compare centers, as currently planned, ambulatory surgery centers that specialize in lens and cataract procedures, which are associated with extremely low hospital transfer rates, may appear to outperform centers specialized in “riskier” procedures solely due to their case mix and not the quality of care provided.30 When measures are ultimately adopted for the ambulatory surgery setting and linked to reimbursement, a rigorous, procedure-specific, risk-standardization process should be used to fairly compare outcomes across centers in addition to broadening the timeframe evaluated for hospital-based, acute care. Future research should evaluate patient and ambulatory surgery center factors associated with more frequent hospital based, acute care among the most common procedures to facilitate the development of appropriate risk standardized models.

This study should be viewed in the context of important limitations. The outcomes in three states may not be generalizable to the U.S. population. This limitation is partly addressed by the states’ geographic diversity and considerable size representing nearly 19% of the total U.S. population in 2010. Additionally, the reliability of the encrypted patient identifiers in the HCUP data vary by State. If a patient does not have a valid identifier, their healthcare could not be tracked. To address this, we selected States with high reliability (≤90%) and few missing data for the encrypted patient identifier. Next, we focused on hospital-based, acute care visits as defined by ED visits or hospital admissions. Patients placed in observation status and visits to physician offices or other ambulatory care sites were not included and may underestimate the total number of discharged patients who require acute care following ambulatory procedures. Finally, it is important to note that we did not attempt to determine the appropriateness or inappropriateness of the subsequent acute care utilization.

In conclusion, the need for hospital-based, acute care within 7-days of discharge from an ambulatory surgery center is substantially more common than the need for transfer to an acute care facility. Our finding that the reasons for these acute care encounters are often related to the ambulatory procedure, along with the finding that rates vary across centers, suggest there may be modifiable factors that could potentially reduce utilization rates. Accordingly, extending current measures of quality beyond the initial discharge may provide a more robust assessment of healthcare quality received in the ambulatory surgical setting. Ambulatory surgery centers should not be evaluated – or financially rewarded or penalized - on the basis of their immediate transfer rate, as this approach provides an incomplete and potentially biased assessment of the quality of care they provide. Future research should identify the underlying patient factors and system failures that result in post-procedure acute care encounters, particularly as an increasing number of patients are treated in ambulatory surgery centers.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr. Ross is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG032886) and by the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. Drs Vashi, Ross and Gross are involved with the Clinical Scholar’s Program that is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Dr. Vashi is also a VA scholar and is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2.

ICD-9-CM coding appendix

| Term | ICD-9-CM Codes |

|---|---|

| Maintenance radiation or chemotherapy | V58.0, V58.1, V58.11, V58.12, V66.1, V66.2, V67.1, V67.2 |

| Rehabilitation services | V52.0, V52.1, V52.4, V52.8, V52.9, V53.8, V57.0, V57.1, V57.2, V57.21, V57.22, V57.3, V57.4, V57.81, V57.89, V57.9, V58.82 |

| Cancer | 140.x-239.x |

| Normal obstetrical delivery | 650, 651.00, 651.01, 651.10, 651.11, 651.20, 651.21, 651.70, 651.71, 651.73, 651.80, 651.81, 651.90, 651.91, V22.0, V22.1, V22.2, V24.0, V24.1, V24.2, V27.0, V27.1, V27.2, V27.3, V27.4, V27.5, V27.6, V27.7, V27.9, V72.4, V72.42, V91.00, V91.01, V91.02, V91.03, V91.09, V91.10, V91.11, V91.12, V91.19, V91.20, V91.21, V91.22, V91.29, V91.90, V91.91, V91.92, V91.99 |

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Health & Human Services or the U.S. Government.

Financial Disclosures: Drs Gross and Ross are members of a scientific advisory board for FAIR Health, Inc. and receive research funding from Medtronic, Inc. to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing. Dr. Ross also receives research funding from the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to develop and maintain performance measures that are used for public reporting and from the Pew Charitable Trusts to examine regulatory issues at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

References

- 1.Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. National health statistics reports. Jan 28;2009(11):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manchikanti L, Parr AT, Singh V, Fellows B. Ambulatory surgery centers and interventional techniques: a look at long-term survival. Pain physician 2011. 2011 Mar-Apr;14(2):E177–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barie PS. Infection control practices in ambulatory surgical centers. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association 2010. 2010 Jun 9;303(22):2295–2297. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roeder KH. CMS criticizes quality oversight of ambulatory surgery centers. GHA today. 2002 Mar;46(3):3, 9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rollins G. Final five: ASCs told to target patient safety. Hospitals & health networks/AHA. 2007 Dec;81(12):53–54. 56, 51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medicare program; revised payment system policies for services furnished in ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) beginning in CY 2008 Final rule. Federal register 2007. 2007 Aug 2;72(148):42469–42626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Outpatient quality reporting slated. OR manager. 2007 Sep;23(9):5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Day LW, Kwon A, Inadomi JM, Walter LC, Somsouk M. Adverse events in older patients undergoing colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2011 Oct;74(4):885–896. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leffler DA, Kheraj R, Garud S, et al. The incidence and cost of unexpected hospital use after scheduled outpatient endoscopy. Archives of internal medicine. 2010 Oct 25;170(19):1752–1757. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melton MS, Klein SM, Gan TJ. Management of postdischarge nausea and vomiting after ambulatory surgery. Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2011 Dec;24(6):612–619. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834b9468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swan BA, Maislin G, Traber KB. Symptom distress and functional status changes during the first seven days after ambulatory surgery. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1998;86(4):739–745. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199804000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pennsylvania_Patient_Safety_Reporting_System. [Accessed April 11, 2012];Unanticipated care after discharge from ambulatory surgical facilities. 2005 http://patientsafetyauthority.org/ADVISORIES/AdvisoryLibrary/2005/dec2(4)/Documents/01b.pdf.

- 13.Coley KC, Williams BA, DaPos SV, Chen C, Smith RB. Retrospective evaluation of unanticipated admissions and readmissions after same day surgery and associated costs. Journal of clinical anesthesia. 2002 Aug;14(5):349–353. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(02)00371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Twersky R, Fishman D, Homel P. What happens after discharge? Return hospital visits after ambulatory surgery. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1997 Feb;84(2):319–324. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199702000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mezei G, Chung F. Return hospital visits and hospital readmissions after ambulatory surgery. Annals of surgery. 1999 Nov;230(5):721–727. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199911000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.HCUP. [Accessed May 8, 2012];Overview of Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2012 http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/overview.jsp.

- 17.HCUP. State Ambulatory Surgery Database (SASD) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) 2009 http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/sasdoverview.jsp.

- 18.HCUP. State Inpatient Database (SID) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) 2009 http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/sidoverview.jsp.

- 19.HCUP. State Emergency Department Database (SEDD) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) 2009 http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/seddoverview.jsp.

- 20.HCUP. [Accessed August 2, 2013];Clinical Classifications Software for Services and Procedures. 2013 http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs_svcsproc/ccssvcproc.jsp.

- 21.HCUP. [Accessed April 16, 2012];Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. 2012 http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

- 22.HCUP. [Accessed January 19, 2013];Clinical Classifications Software for Services and Procedures. 2013 http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs_svcsproc/ccssvcproc.jsp.

- 23.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998 Jan;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Medical care. 2005 Nov;43(11):1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keenan PS, Normand SL, Lin Z, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance on the basis of 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with heart failure. Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2008 Sep;1(1):29–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.802686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Drye EE, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2011 Mar;4(2):243–252. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schabenberger O. [Accessed October 10, 2012];Introducing the GLIMMIX Procedure for Generalized Linear Mixed Models. http://www.google.com/url?q=http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi30/196-30.pdf&sa=U&ei=8VV3UOTBA-iQ0QGc1ICwAg&ved=0CBQQFjAA&usg=AFQjCNGchcE-0-Da79pU3o0JR846wR4fOA.

- 28.Carey K, Burgess JF, Jr, Young GJ. Hospital competition and financial performance: the effects of ambulatory surgery centers. Health economics. 2011 May;20(5):571–581. doi: 10.1002/hec.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frakes JT. The ambulatory endoscopy center (AEC): what it can do for your gastroenterology practice. Gastrointestinal endoscopy clinics of North America. 2006 Oct;16(4):687–694. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyerhoefer CD, Colby MS, McFetridge JT. Patient mix in outpatient surgery settings and implications for medicare payment policy. Medical care research and review: MCRR. 2012 Feb;69(1):62–82. doi: 10.1177/1077558711409946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]