Abstract

Even though pregnancy is rare with cirrhosis and advanced liver disease, but it may co-exist in the setting of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension as liver function is preserved but whenever encountered together is a complex clinical dilemma. Pregnancy in a patient with portal hypertension presents a special challenge to the obstetrician as so-called physiological hemodynamic changes associated with pregnancy, needed for meeting demands of the growing fetus, worsen the portal hypertension thereby putting mother at risk of potentially life-threatening complications like variceal hemorrhage. Risks of variceal bleed and hepatic decompensation increase many fold during pregnancy. Optimal management revolves round managing the portal hypertension and its complications. Thus management of such cases requires multi-speciality approach involving obstetricians experienced in dealing with high risk cases, hepatologists, anesthetists and neonatologists. With advancement in medical field, pregnancy is not contra-indicated in these women, as was previously believed. This article focuses on the different aspects of pregnancy with portal hypertension with special emphasis on specific cause wise treatment options to decrease the variceal bleed and hepatic decompensation. Based on extensive review of literature, management from pre-conceptional period to postpartum is outlined in order to have optimal maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Keywords: pregnancy, portal hypertension, cirrhosis, non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis, Portal vein thrombosis

Abbreviations: ACOG, American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology; EHPVO, extrahepatic portal vein obstruction; EST, endoscopic sclerotherapy; EVL, endoscopic variceal ligation; FDA, Food & Drug Association of America; HVPG, hepatic vein pressure gradient; NCPF, non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis; NCPH, non-cirrhotic portal hypertension; PPH, postpartum hemorrhage; PVT, portal vein thrombosis

Pregnancy associated with liver diseases is an infrequent situation, but when seen together, presents a complicated clinical situation. Portal hypertension develops as a result of number of etiologies. In the west, cirrhosis is the commonest cause of portal hypertension. In the setting of cirrhotic portal hypertension, pregnancy is very rare due to hepatocellular damage leading to amenorrhea and infertility, the incidence of cirrhosis in pregnancy has been reported as 1 in 5950 pregnancies.1 Cirrhosis may get exacerbated during pregnancy and has significant adverse effects on the mother and the baby.2–4 In the developing countries, other causes like extrahepatic portal vein obstruction contribute significantly to non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH). Mostly liver function is much better preserved in women with NCPH and pregnancy is spontaneous in these women. Portal hypertension associated with pregnancy is a high risk situation as both pregnancy and portal hypertension share some of the hemodynamic changes. The physiological changes, in adaptation to the pregnancy and fetal needs, worsen the portal hypertension resulting in potentially life- threatening variceal bleed and other complications. Pregnancy is a potential hazard for occurrence of recurrent variceal bleed due to its hyperdynamic state causing increase in flow to the collaterals.5–7 Therefore management in pregnancy requires knowledge of both the effects of changes during pregnancy on portal hemodynamics and the effects of portal hypertension and its cause on both mother and fetus, hepatotoxicity of the drugs used, management of portal hypertension so as to have an optimal pregnancy outcome. This review deals with various aspects of pregnancy with portal hypertension including cirrhotic as well as non-cirrhotic causes and focuses on the treatment options.

Physiological changes of pregnancy

Numerous hemodynamic and physiological changes occur during pregnancy as an adaptation to the needs of the growing fetus.8,9 These changes start as early as six weeks and peak around 32 weeks. These changes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Normal Physiological Changes During Pregnancy.

| 1. | ↑ Maternal blood volume |

| 2. | ↑ Maternal heart rate |

| 3. | ↑ Maternal blood volume |

| 4. | ↓ Systemic vascular resistance and blood pressure |

| 5. | Peripheral vasodilatation & placental bed circulation. |

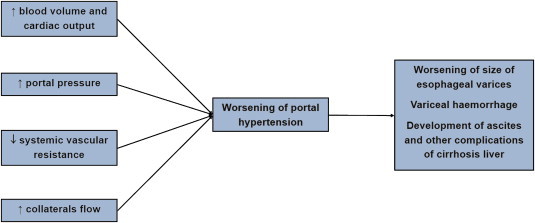

One of the earliest changes is an increase in plasma output by 40–50%. Maternal cardiac output increases by 30–50% due to increase in stroke volume and the heart rate. There is decline in systemic vascular resistance as a result of progesterone effect and development of placental vascular bed. As a result of all of these changes, there is a profound alteration in systemic hemodynamics resulting in a hyperdynamic state with increased pulse pressure. These changes can worsen the portal hypertension in pregnant patients with portal hypertension and markedly increase the risks of variceal hemorrhage.9 In patients suffering from liver cirrhosis, splanchnic arterial vasodilatation occurs, due to an increased local release of nitric oxide and other vasodilators related to portal hypertension, resulting in severely impaired circulatory function.10,11 Consequently compensatory mechanisms essential in maintenance of arterial pressure in cirrhotic patients, unfortunately result in development of marked hemodynamic disturbances known as hyperdynamic syndrome. The pregnant woman has a 20–27% chance of esophageal bleed which increases markedly in case she has demonstrable varices.9

Pathophysiology of Portal Hypertension

Portal hypertension most commonly results from cirrhosis. Due to irreversible progressive damage in cirrhosis, these women usually have amenorrhea and infertility. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension can be encountered without evidence of liver disease. The first known mechanism of portal hypertension is an increase in intrahepatic resistance to blood flow. Hepatic damage thus caused results in shunting of hepatic blood, development of extrahepatic collaterals and elevated pressure in the portal venous system.12 The normal portal pressure is 4–8 mm of mercury. Hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG = wedge hepatic pressure- free hepatic pressure) is used as a reflection of the portal pressure, and considered to be the gold standard for measuring portal pressure. It helps to guide therapy and prognosis in cirrhotic patients who have had a previous history of variceal bleed. Normal values of HVPG are between 1 and 5 mmHg, portal hypertension is defined as the pathologic increase in portal pressure expressed as HVPG. An HVPG>10 mmHg is needed for development of esophageal varices and HVPG >12 mmHg for them to bleed (Table 2).13,14

Table 2.

Pathophysiological Effects of Portal Hypertension.

| HPVG (mm Hg) | Clinical features | Stage of cirrhosis |

|---|---|---|

| 1–5 | Normal, non-cirrhotic | – |

| 6–10 | Compensated cirrhosis | 1 |

| >10 | Compensated cirrhosis with development of varices | 2 |

| >12 | Decompensated cirrhosis with ascites, variceal bleed, hepatic encephalopathy | 3–4 |

Variceal bleeding, ascites, encephalopathy and hepatorenal syndrome are the various clinical manifestations of the portal hypertension. Esophageal varices are seen in >40% of patients with liver cirrhosis at the time of diagnosis. Other manifestations of portal hypertension are splenomegaly and hypersplenism (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of pregnancy hemodynamics on portal hypertension.

Effect of Portal Hypertension on Pregnancy

In pregnant women, alcoholic cirrhosis is uncommon while viral or autoimmune related cirrhosis is more common in developing countries. The non-cirrhotic causes of portal hypertension include extra-hepatic portal vein obstruction, non cirrhotic portal fibrosis, portal vein thrombosis, Budd–Chiari syndrome, infection or congenital hepatic fibrosis.15

Maternal Complications

The complications of portal hypertension in pregnancy pose multiple risks to the mother and the fetus. In pregnancies with portal hypertension 30%–50% of pregnancy suffer from portal hypertension associated complications, resulting mainly because of variceal bleed and hepatic failure.15 The severity of complications depends on the cause of portal hypertension and disease severity. These include variceal bleed, severe anemia, hepatic decompensation leading to progressive liver and renal failure, hepatic encephalopathy, splenic artery aneurysm rupture, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and post-partum hemorrhage.

Esophageal Varices

Gastro-intestinal hemorrhage remains the most catastrophic complication of portal hypertension during pregnancy. Variceal bleed has been reported in 18–32% of pregnant patients with cirrhosis and in 50% with a known portal hypertension. About 75% of patients with varices bleed during pregnancy which is one of the most serious consequences.16 This is due to increased flow and pressure transmitted to collaterals due to hyperdynamic circulation during pregnancy. The dreaded complication of active variceal bleeding may occur at all stages of the pregnancy though second and third trimester and second stage of labor are the time of greatest risks of variceal bleed. Predictors of variceal bleed during pregnancy associated with portal hypertension are large varices, presence of endoscopic red signs and history of pre conceptional variceal bleed and untackled or undiagnosed varices.16 In cirrhotic portal hypertension, nearly half of the women bleed during pregnancy. Patients with portal hypertension associated with liver cirrhosis have worst prognosis, with mortality rate of 18–50% whereas those with primary biliary cirrhosis have the best outcome. Pregnant women with NCPH fare better with a mortality rates between 2 and 6%.15 Approximately 7–9% of patients with portal hypertension suffer from symptomatic anemia irrespective of the cirrhotic state.16 The poorer prognosis in cirrhosis may be due to underlying severe liver damage and coagulopathy.

In case of active bleed, immediate resuscitation and stabilization of the mother is required along with intensive monitoring and emergency treatment of varices. The upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is safe in pregnancy with a small risk of fetal hypoxia from sedation and patient positioning. The mainstay of treatment remains endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL),17–19 the first case during pregnancy was reported by Starkel et al20 Endoscopic sclerotherapy has also been reported by a few,21–24 however EVL remains the preferred choice as it avoids any potential risk of sclerosant injection. Medical therapy with vasopressors for acute variceal bleeding have a role. Terlipressin is a category D drug hence is avoided whereas octreotide, a category B drug has not been well studied in pregnant patients. Octerotide may be used but some authors do mention risks associated with it. Third generation cephaosporins can be used for prophylaxis against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in the event of a variceal bleed but fluoroquinolones are contra indicated in pregnancy. Pregnant patients at risk for variceal bleed should receive primary prophylaxis, with either endoscopic variceal ligation or β blockers. β blockers are generally considered safe in pregnancy however propranolol and nadolol both carry category C risk and have risk of causing fetal bradycardia, growth retardation and neonatal hypoglycaemia. Screening for esophageal varices is recommended by most experts during the early second trimester or before pregnancy. Although Transjugular intrahepatic portal shunt (TIPS) placement is considered a contraindication during pregnancy due to the risk of fetal radiation exposure, they are done only if medical treatment or endoscopic procedures fail to control the variceal hemorrhage. These surgical procedures are associated with increased incidence of encephalopathy, fetal radiation risk, but may be a rescue treatment. The risk of fetal malformations from radiation is thought to be increased at doses above 150 mGy and is considered negligible if doses are below 50 mGy.25 Only three cases of TIPS placement have been reported in pregnant patients with cirrhosis and all three survived the episode of variceal bleed.26–28 Patients with splenorenal or portacaval shunts have been shown to be associated with lower risk of spontaneous abortion or severe gastrointestinal hemorrhage than pregnant patients without shunts.29

Hepatic Decompensation and Maternal Mortality

Another complication in these women is hepatic decompensation leading to hepatic encephalopathy which may develop secondarily to variceal bleed, infections, drugs used or hypotension.29 Pregnant patient with cirrhosis may develop liver dysfunction in the form of jaundice, ascites, and/or hepatic encephalopathy in 24%.3 Hepatic decompensation may occur during all stages of pregnancy but often occurs after episodes of variceal bleeding.30 Hepatic encephalopathy may be precipitated by drugs such as benzodiazepines, tranquilizers, sedatives, etc, infection, bleeding, electrolyte imbalance, hypotension etc. Therefore these factors should be looked for carefully and treated appropriately. The mainstay of treatment is anti-hepatic coma regime using both lactulose and antibiotic therapy. Rifaximin is category C drug and metronidazole is category B drug, hence metronidazole may be preferred. Renal dialysis is the modality for hepato-renal shutdown. Terlipressin is contra-indicated in pregnancy as it may exert oxytocic effect.

Ascites

Ascites is seen to develop in women with cirrhosis of liver and are more prone to develop spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Although cases of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis have not been reported, the risk of preterm delivery and placental abruption is seen to increase if other forms of peritonitis develop. Treatment includes salt restriction, and use of diuretics. Mortality rate is high if not treated early and adequately. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is usually treated with 3rd generation cephalosporins.

Postpartum Hemorrhage

These patients are at a high risk of post-partum hemorrhage which occurs in 7%–10% of cases and is commoner in patients with cirrhosis. Post-partum hemorrhage may be due to associated coagulopathy as a result of liver dysfunction and thrombocytopenia due to hypersplenism associated with portal hypertension or cirrhosis per se. The treatment remains the same as those in patients without cirrhosis of liver. These patients require blood and coagulation factors along with uterine contractile agents such as oxytocin. Prevention by active management of third stage of labor is the mainstay of management.

Splenic Artery Aneurysm Rupture

Development of splenic arterial aneurysm is a rare cause of mortality in patients of cirrhosis with portal hypertension, which may rupture during pregnancy and can present with sudden abdominal pain and hemodynamic collapse resulting in maternal and perinatal mortality rate of 70% and 80% respectively.31–33 High estrogen levels, increased blood flow from pregnancy and portal hypertension are the likely underlying mechanisms. Splenic artery aneurysmal rupture may occur in 2.6% of pregnant women with cirrhosis of liver. Twenty percent of all splenic artery aneurysm rupture occur during pregnancy. Most of the ruptures (70%) occur in the third trimester necessitating emergency laparotomy, ligation of the aneurysm or splenectomy. Surgery may be technically very difficult in such cases, a transcatheter embolization may be the preferred option.

Perinatal Mortality Due to Underlying Cause

Fetal outcome may be affected by underlying cause of liver disease as in cases of Budd- Chiari syndrome, the underlying prothrombotic condition may lead to adverse fetal outcome.34,35 Various studies reported till date have been compiled in Table 3.36−46

Table 3.

Literature Review: Pregnancy Outcome with Portal Hypertension.

| Study36–46 | Cause of portal hypertension | No. of patients/Pregnancies | Complications | Pregnancy outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variceal bleed (%) | Decompen-sation (%) | Abortion | Still birth | Live birth | |||

| Aggarwal et al 201138 | EHPVO | 14/27 | 9 (33.3%) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Mandal et al 201244 | EHPVO | 24/41 | 10 (24%) | 3a | 2 | 39 | |

| Ducarme et al 200942 | PV Cavernoma | 2/2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hoekstra et al 201245 | PVT | 24/45 | 3 (6.9%) | 4 | 9 (20%) | 36 | |

| Sumana et al 200839 | NCPH | 5/12 | 2 (16.6%) | 3 | 3 | – | 9 |

| Aggarwal et al 200141 | NCPH | 27/50 | 17 (34%) | 1 | 10 | 6 | 34 |

| Kochhar et al 199936 | NCPH | 44/116 | 13.8% | – | 7% | – | 107 |

| Pajor et al 199446 | cirrhosis | 11/12 | 42% | 25% | 8% | ||

| Aggarwal et al 199937 | Cirrhosis | 7/9 | 1 (11.9%) | 3a | 1 | – | 8 |

| Shaheen et al 201040 | cirrhosis | 339/339 | 5.5% | 15%a | 6% | ||

| Westbrook et al 201143 | cirrhosis | 29/62 | 3 | 3a | 27% | 4 | 36 |

EHPVO – Extra hepatic portal vein obstruction, PVT – Portal vein thrombosis, NCPH – Noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

Includes one maternal death.

Perinatal Complications

The rates of spontaneous abortion, premature birth, still births and perinatal death are increased in women with portal hypertension. There is 10%–66% fetal wastage in patients of liver cirrhosis and spontaneous abortion rate of about 20% first trimester abortion.47,48 Patients with causes like extrahepatic portal venous obstruction not associated with cirrhosis have portal hypertension with preserved liver function and have similar rates of spontaneous abortion as in the general population of 3%–6%, these patients also have better fertility than the patients with liver cirrhosis.49 In patients with portal hypertension perinatal mortality is increased to 11–18%.40,41 Sumana et al39 reported no increase in the incidence of hematemesis in pregnant women with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. From the literature review, it is evident that all maternal and perinatal complications are much higher in cirrhotic portal hypertension.50–52 Incidence of abortion and pre-term labor is increased in case of variceal bleed during pregnancy. Perinatal mortality due to prematurity is now on decline with availability of measures such as use of corticosteroids and surfactant, and management of new-borns in neonatal intensive care units..

Prognostic Predictors

There are various scoring systems in clinical practice to assess the severity of liver disease and these are basically used as a guide for allocation of organs in liver transplantation scores. These include the model for end- stage liver disease (MELD), the UK end- stage liver disease (UKELD), MELD-sodium (MELD-Na).43 Westbrook et al recently in a study, assessed the course of 62 pregnancies and their outcome in 29 women with cirrhosis and correlated with MELD, UKELD, MELD- Na scores. They demonstrated that MELD and UKELD scores at conception can be used to predict likely outcomes of pregnancy in the cirrhotic patients. Patients with a MELD score of 6 or less can be reassured of minimal significant complications and those with MELD score of 10 or above should be advised against pregnancy.43

Management

Pregnancy in a patient with portal hypertension requires a multispecialty team approach including expert obstetrician, hepatologist, neonatologist and anesthesiologist in a tertiary care center with facilities and expertise for gastrointestinal endoscopy, portal vascular surgery, high-risk pregnancy unit, perinatal and adult intensive care unit.

Pre-conception Counseling

Extensive and detailed pre-conceptional counseling, evaluation and antenatal and perinatal monitoring is needed in patients with portal hypertension with or without cirrhosis planning for pregnancy. A complete medical history, detailed examination, lab investigations and imaging studies need to be performed to assess the cause of the disease and its status. Various poor predictors of a successful pregnancy with portal hypertension include history of variceal bleed, large varices, presence of other co-morbidities like jaundice, thrombocytopenia, ascites, hypersplenism, etc. Patient should be explained about the various effects of pregnancy on portal hypertension, risks of complications due to disease and drug toxicity and various added specific complications depending on the cause of disease as in patients with viral cirrhosis, the risk of transmission of viral infection to the new born. Contraception advice should be given in the acute phase of disease, in case of complications, or if a liver transplant is likely. Pregnancy should only be planned when the liver disease is stable and the patient agrees for regular follow-up and close monitoring during the entire pregnancy and the postnatal period.

Surveillance endoscopy should be done in the pre-conceptional period. Varices should be tackled prior to planning a pregnancy, endoscopic variceal ligation is the preferred therapy and non-responders should be offered surgery in the form of shunt procedure or splenectomy. Women with Budd–Chiari syndrome should have treatment of the venous outflow obstruction and disease under control prior to planning a pregnancy.34,35

Drugs should be reviewed for adverse effects on the fetus and alternative safe drugs to be changed, and also dose needs to be tailored. Prednisolone and azathioprine, if needed, can be continued in the minimum effective doses. Spironolactone should preferably be discontinued. Selective β blockers can be continued as their benefits outweigh risks. The genetically transmissible and infectious conditions also need to be identified and counseling done accordingly. Medical termination of pregnancy may be advised in case of severe hepatic decompensation like ascites, encephalopathy, and liver failure.

Antenatal Management

Maternal and fetal prognosis is dependent on the cause of underlying liver disease and its status at the time of conception. Pregnancy is not a contra-indication if the disease is well compensated. Antenatal management requires strict maternal and fetal monitoring by a multi-disciplinary team. The routine antenatal management should be given with special watch out for the potential complications like variceal bleed and liver failure. Anemia should be avoided and if present treated emphatically as anemia itself also leads to cardiac compromise in addition to being a risk factor for pre- term labor, low birth weight. Liver function and hematological assessment should be done 4 weekly, fetal growth needs to be monitored vigilantly and effects of the drugs need to be watched. Close maternal and fetal monitoring by the joint team is recommended two weekly. The principles of management include anticipation, early recognition and management of the antenatal complications associated with portal hypertension.

Since variceal bleed is the single important complication linked with poor pregnancy outcome, the basic aim is to prevent it and that can be done by assessment and tackling the varices prior to planning a pregnancy. In cases of unplanned pregnancy, proper risk assessment should be performed. Endoscopy is the gold standard to assess the risk of bleeding in patients with esophageal varices. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is safe during pregnancy,53 the main risk being fetal hypoxia due to sedation or positioning. Risk of variceal hemorrhage is higher in patients with medium or large esophageal varices. Current American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) recommendations include screening endoscopy in the second trimester as that is the time of maximum increase in the portal pressure.54 The treatment options in presence of esophageal varices are both medical and surgical. There are no definite recommended guidelines of varices during pregnancy, these are based on the best guess experience extrapolated from the non- pregnant state. There are no definite guidelines on primary prophylaxis for varices during pregnancy, the opinion is extrapolated from the studies from non-pregnant patients. In a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the primary prophylaxis of gastric variceal bleed, Mishra et al recommended primary prophylaxis in patients with large and high risk gastric varices to reduce the risk of first bleed and mortality.55 Though non-selective beta blockers used to reduce portal pressure also reduce the risk of first bleed by half but the principal risk of using them in pregnancy is fetal growth restriction and fetal bradycardia. EVL of the large varices can also be done during pregnancy to prevent variceal bleeding. Current literature (Baveno V consensus workshop) recommends EVL for acute esophageal variceal bleed, although, endoscopic sclerotherapy may be used if banding is technically difficult.17 In case of failure to control bleeding endoscopically by EVL or endoscopic sclerotherapy, emergency transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt procedure may be needed.56 Aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided. There are no controlled trials for efficacy and safety of medical versus surgical treatment during pregnancy, most of the reports are from cirrhosis patients.

Pregnancy can be allowed to go to term if the disease is well compensated. Early termination of pregnancy may be warranted in case of any obstetrical indication or progressive liver failure. In case of planned termination before 34 weeks, antenatal corticosteroids can be administered for fetal lung maturity. There are no recommendations as to the preferred mode of delivery- vaginal vs caesarean section in patients with portal hypertension. The Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) has developed consensus statement on various aspects of extra-hepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) including pregnancy and recommended that vaginal delivery can be anticipated in most of these women.57 Cesarean is usually reserved for the obstetrical indications.

Peripartum management

The management during labor needs to be individualized depending on cause of portal hypertension and the disease status. Adequate amount of blood and plasma should be arranged and measures for balloon tamponade for the variceal hemorrhage must be handy. While carrying out delivery in such patients, obstetricians must take care of volume and fluid overload, coagulation disorders, raised intra-abdominal pressure, various drugs administered. Platelet transfusion may be needed in the intra-partum period in cases of hypersplenism. Intravenous labor analgesia or epidural analgesia can be given if there is no coagulopathy. Spinal anesthesia may lead to hypotension and also may be contra-indicated due to thrombocytopenia. Drugs used in general anesthesia may precipitate encephalopathy. If general anesthesia is given, precautions need to be taken at the time of extubation to reduce aspiration. Epidural analgesia, in fact, is the preferred choice as it can also work in case caesarean is required. Delivery should be conducted under supervision of the senior obstetrician. Second stage of labor may be shortened prophylactically to avoid overstraining by the mother.58 The third stage should be managed actively; methergin should be avoided amongst the oxytocics. Postpartum hemorrhage should be anticipated and managed vigilantly. Antibiotics use needs to be individualized. Caesarean delivery is usually carried out in case of obstetric indications. Vascular surgeon may be needed to tackle the bleeding from ectopic varices in the operative field.

Postpartum management

The postpartum management entails strict vigilance for postpartum hemorrhage. Antibiotics should be given in the postpartum period. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a specific complication which may develop in the puerperium especially in the presence of ascites. Puerperal fever should be investigated and treated with appropriate antibiotics. In case of cirrhosis associated with infective etiology like chronic hepatitis B, vertical transmission to the neonate needs to be avoided by giving immunoglobulin to the neonate at birth and hepatitis B vaccine. Breast feeding is usually not contra-indicated in these women unless she is on some FDA category D or X drugs. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) guidelines recommend breast feeding for mothers with hepatitis C and B though in cases of hepatitis B, it should be started after immunoglobulin administration to the neonate.59,60 Reliable contraception must be advised in the form of barrier methods, intra uterine devices or permanent sterilization. However, permanent sterilization may not be feasible in the presence of coagulopathy. Hormonal contraception is usually avoided as they can cause cholestasis.

Pregnancy After Liver Transplantation

The success of liver transplantation program has changed the course of events of pregnancy in cirrhosis.19 Successful pregnancies have been reported after liver transplant.61–66 In the National Transplant Registry from USA, 202 pregnancies have been reported in 121 liver transplant recipients.65 The incidence of prematurity, low birth weight, pregnancy induced hypertension and caesarean was found to be higher. This may be due to immunosuppressive agents. A population based cohort study found higher rates of caesarean section in patients with cirrhosis (adjusted OR-2.4) and prior liver transplant (adjusted OR-1.8) when compared to general obstetrical population.67 The rates of preterm labor, peripartum infection, and hypertension were also higher. Cirrhotic women had higher rates of death, venous thromboembolism, malnutrition, placental abruption and peripartum blood transfusions. Decompensated cirrhosis had higher rates of caesarean delivery, preterm labor, placenta previa and peripartum blood transfusions than women with compensated cirrhosis. Mycophenolate has been reported to be associated with first trimester loss and increased congenital malformations.68 The graft rejection is higher if pregnancy occurs within 6 months of transplant.69 Pregnancy should be postponed for at least one year post transplant to ensure adequate graft functioning and lowest doses of immune suppressants and reduced incidence of infections and acute rejection of graft.

Drugs used in liver disease

Majority of the drugs used in portal hypertension or after liver transplant (propranolol, furosemide, lamivudine, interferon, entecavir etc.) are FDA category C drugs (i.e. risk cannot be ruled out). Azathioprine, d-penicillamine are category D drugs with possible fetal harm shown by animal studies. Ribavarin is category X drug and contra-indicated during pregnancy. Lactulose, octreotide, telbivudine, prednisolone and ursodeoxycholic acid are pregnancy category B drugs with no harmful effects shown by animal studies. However, lamuvidine use has been extensively reported in HIV infected women during pregnancy and shown to be well tolerated and safe.70

Thus, to conclude, pregnancy with portal hypertension may be associated with adverse maternal and perinatal outcome especially in cirrhotic portal hypertension but pregnancy is not contra-indicated as was once believed. Better outcomes can be expected in the modern era with better diagnostic and treatment modalities. Physicians and obstetricians need to be conversant with the unique complications and risks. These include mainly hemorrhage (due to variceal bleed, splenic artery aneurysmal rupture, postpartum bleed) or hepatic failure. Management needs to be individualized. Emphasis must be laid down or pre-conceptional counseling, stabilization of the disease, treatment of esophageal varices, liver transplant if deemed necessary. A multi- disciplinary team approach in a tertiary care unit with availability of intensive care units is likely to yield best pregnancy outcomes in women with portal hypertension.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

Box: key points.

-

▸

Portal hypertension is associated with cirrhosis and non-cirrhotic causes. Pregnancy is rare in cirrhotics, but is common in women with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension.

-

▸

Recent improvements in treatment of cirrhosis have resulted in a greater number of pregnancies in these women.

-

▸

Normal physiological hemodynamic changes of pregnancy worsen the portal hypertension thereby increasing the risks of life-threatening variceal bleed and hepatic failure.

-

▸

Pregnancy outcome depends on the disease status and presence of esophageal varices at the time of conception.

-

▸

Pre-pregnancy counseling is very important and pregnancy should be allowed only when the disease is stable and there are no complications.

-

▸

These women should be managed in a tertiary health care system by a multi-disciplinary team.

-

▸

Management of esophageal varices is similar as in the non-pregnant state. Endoscopic variceal ligation is recommended in case of variceal bleed, sclerotherapy if endoscopic variceal ligation is technically difficult. Surgery and transhepatic intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt procedures are undertaken only as rescue.

-

▸

Risks specific to the underlying disease must be considered and tackled accordingly and drugs modified. Second stage of labor needs to be shortened. Active management of third stage, vigilant look-out for postpartum hemorrhage and prompt treatment is necessary for optimal pregnancy outcome.

References

- 1.Peitsidou A., Peitsidis P., Michopoulos S., Matsouka C., Kioses E. Exacerbation of liver cirrhosis in pregnancy: a complex emerging clinical situation. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279:911–913. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0811-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Misra S., SanyalAJ Pregnancy in a patient with portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 1999;3:147–162. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjaminov F.S., Heathcote J. Liver disease in pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2479–2488. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng Y.S. Pregnancy in liver cirrhosis and/or portal hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977;128:812–822. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(77)90727-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein H.H., Pich S. Cardiovascular changes during pregnancy. Herz. 2003;28:173–174. doi: 10.1007/s00059-003-2455-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Dyke R.W. The liver in pregnancy. In: Zakin D., Boyer T.D., editors. 3rd ed. vol. 2. WB Sauders Philadelphia; 1996. pp. 1734–1759. (Hepatology. A Text Book of Liver Disease). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiribelli C., Rigato I. Liver cirrhosis and pregnancy. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5:201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crickshank D., Wigton T., Hays P. Maternal physiology in pregnancy. In: Gabb S., Nieby J., Simpson J., editors. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. Churchil Livingstone; New York: 1996. pp. 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez-Mendes Eric. Lourdes Avila-Escobedo. Pregnancy and portal hypertension a pathology view of physiologic changes. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5:219–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrier R.W., Arroyo V., Bernardi M., Epstein M., Henriksen J.H., Rodes J. Peripheral arterial vasodilatation hypothesis: a proposal for the initiation of renal sodium and water retention in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1988;8:1151–1157. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiest R., Groszmann R.J. The paradox of nitric oxide in cirrhosis and portal hypertension: too much, not enough. Hepatology. 2002;35:478–491. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bathal P.S., Groszmann R.J. Reduction of the increased portal vascular resistance of the isolated perfused cirrhotic rat liver by vasodilators. J Hepatol. 1985;1:325–329. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(85)80770-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosch J., Mastai R., Kravetz D., Navasa M., Rodes J. hemodynamic evaluation of the patient with portal hypertension. Semin Liver Dis. 1986;6:309–317. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Tsao G., Friedman S., Iredale J., Pinzani M. Now there are many (stages) where before there was one: In search of a pathophysiological classification of cirrhosis. Hepatol. 2010;51:1445–1449. doi: 10.1002/hep.23478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandhu B.S., Sanyal A.J. Pregnancy and liver disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:407–436. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(02)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell M.A., Craigo S.D. Cirrhosis and portal hypertension in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 1998;22:156–165. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(98)80048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.deFranchis R. Baveno V faculty. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qureshi W., Adler D.G., Davila R. ASGE Guideline: the role of endoscopy in the management of variceal hemorrhage, updated. Gastrointest Endosc. July 2005;2005(62):651–655. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan J., Surti B., Saab S. Pregnancy and cirrhosis. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:1081–1091. doi: 10.1002/lt.21572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Starkel P., Horsmans Y., Geubel A. Endoscopic band ligation: a safe technique to control bleeding esophageal varices in pregnancy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:212–224. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kochhar R., Goenka M.K., Mehta S.K. Endoscopic sclerotherapy during pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1132–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhiman R.K., Biswas R., Aggarwal N. Management of variceal bleed in pregnancy with endoscopic variceal ligation and N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate: report of three cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:91–93. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70398-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwase H., Morise K., Kawase T., Horiuchi Y. Endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for esophageal varices during pregnancy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;18:80–83. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199401000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pauzner D., Wolman I., Niv D., Ber A., David M.P. Endoscopic sclerotherapy in extrahepatic portal hypertension in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:151–153. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90646-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parry R.A., Glaze S.A., Archer B.R. The AAPM/RSNA physics tutorial for residents. Typical patient radiation doses in diagnostic radiology. Radiographics. 1999;19:1289–1302. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.5.g99se211289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wildberger J.E., Vorwerk D., Winograd R., Stargardt A., Busch N., Gunther R.W. New TIPS placement in pregnancy in recurrent esophageal varices haemorrhage-assessment of fetal radiation exposure (in German) Rofo. 1998;169:429–431. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1015312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savage C., Patel J., Lepe M.R., Lazzare C.H., Rees C.R. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation for recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding during pregnancy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:902–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeeman G.G., Moise K.J. Prophylactic banding of severe esophageal varices associated with liver cirrhosis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:842. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00438-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schreyer P., Caspi E., El Hindi M., Eshchar J. Cirrhosis pregnancy and delivery: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1982;37:304–312. doi: 10.1097/00006254-198205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith J.L., Graham D.Y. Variceal hemorrhage. A critical evaluation of survival analysis. Gastroenterol. 1982;82:968–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hillemanns P., Knitza R., Muller-Hocker J. Rupture of splenic artery aneurysm in a pregnant patient with portal hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1665–1666. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70632-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattar S.G., Lumsden A.B. The management of splenic artery aneurysms: experience with 23 cases. Am J Surg. 1995;169:580–584. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pasha S.F., Gloviczki P., Stanson A.W., Kamath P.S. Splanchnic artery aneurysms. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:472–479. doi: 10.4065/82.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aggarwal N., Suri V., Chopra S., Sikka P., Dhiman R.K., Chawla Y.K. Pregnancy outcome in Budd–Chiari Syndrome – a tertiary care centre experience. Arch Gynecol Obst. 2013;288:948–952. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-2834-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rantou P.E., Angermayr B., Garcia-Pagan J.C. Pregnancy in women with known and treated Budd–Chiari syndrome : maternal and fetal outcomes. J Hepatol. 2009;51:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kochhar R., Kumar S., Goel R.C., Sriram P.V., Goenka M.K., Singh K. Pregnancy and its outcome in patients with non cirrhotic portal hypertension. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1356–1361. doi: 10.1023/a:1026687315590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aggarwal N., Sawhney H., Suri V., Vasishta K., Jha M., Dhiman R.K. Pregnancy and cirrhosis of the liver. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;39:503–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1999.tb03145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aggarwal N., Chopra S., Raveendran A., Suri V., Dhiman R.K., Chawla Y.K. Extra hepatic portal vein obstruction and pregnancy outcome: largest reported experience. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:575–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sumana G., Dadhwal V., Deka D., Mittal S. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34:801–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaheen A.A., Myers R.P. The outcomes of pregnancy in patients with cirrhosis: population based study. Liver Int. 2010;30:275–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aggarwal N., Sawhney H., Vasishta K., Dhiman R.K., Chawla Y. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension in pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;72:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ducarme G., Pessier A., Thullier C., Ceccaldi P.F., Valla D., Luton D. Pregnancy and delivery in patients with portal vein cavernoma. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;68:196–198. doi: 10.1159/000232944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westbrook R.H., Yeoman A.D., O'Grady J.G., Harrison P.M., Delvin J., Heneghan M.A. Model for end-stage liver disease score predicts outcome in cirrhotic patients during pregnancy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:694–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mandal D., Dattaray C., Sarkar R., Mandal S., Choudhry A., Maity T.K. Is pregnancy safe with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction? Singapore Med J. 2012;53:676–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoekstra J., Seijo S., Rautou P.E. Pregnancy in women with portal vein thrombosis: results of a multicentric European study on maternal and fetal management and outcome. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1214–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pajor A., Lehoczky D. Pregnancy in liver cirrhosis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1994;38:48–50. doi: 10.1159/000292444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Britton R.C. Pregnancy and esophageal varices. Am J Surg. 1982;143:421–425. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Varma R.R., Michelson N.H., Borkowf H.I., Lewis J.D. Pregnancy in cirrhotic and non cirrhotic portal hypertension. Obstet Gynecol. 1977;50:217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodrich M.A., James E.M., Baldus W.P. Portal vein thrombosis associated with pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1993;38:969–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindor K.D., Gershwin M.E., Poupon R. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:291–308. doi: 10.1002/hep.22906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goh S.K., Gull S.E., Alexander G.J. Pregnancy in primary biliary cirrhosis complicated by portal hypertension: report of a case and review of the literature. BJOG. 2001;108:760–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whelton M.J., Sherlock S. Pregnancy in patients with hepatic cirrhosis. Management and outcome. Lancet. 1968;2:965–968. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)91294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O'Mahony S. Endoscopy in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:893–899. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia-Tsao G., Sanyal A.J., Grace N.D., Carey W., Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology Prevention and management of gasteroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922–938. doi: 10.1002/hep.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mishra S.R., Sharma B.C., Kumar A., Sarin S.K. Primary prophylaxis of gastric variceal bleeding comparing cyanoacrylate injection and beta blockers: a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2011;54:1161–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lodato F., Cappelli A., Montagnani M. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: a case report of rescue management of unrestrainable variceal bleeding in a pregnant woman. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:387–390. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarin S.K., Sollano J.D., Chawla Y.K. Consensus on extra-hepatic Portal vein obstruction. Liver Int. 2006;26:512–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heriot J.A., Steven C.M., Sattin R.S. Elective forceps delivery and extradural anaesthesia in a primigravida with portal hypertension and esophageal varices. Br J Anes. 1996;76:325–327. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Committee on Obstetric Practice. American college of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion. Breast feeding and the risk of hepatitis C virus transmission. Number 220, August 1999. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;66:307–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang J.S., Zhu Q.R., Wang X.H. Breast feeding does not pose any additional risk of immunoprophylaxis failure on infants of HBV carrier mothers. Int J Clin Pract. 2003;57:100–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fair J., Kein A., Feng T. Intrapartum orthotopic transplantation with successful outcome of pregnancy. Transplantation. 1990;50:534–535. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199009000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hamilton M.I., Alcock R., Mags L., Mallett S., Rolles K., Burroughs A.K. Liver transplantation during pregnancy. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:2967–2968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Laifer S., Darby M. Pregnancy and liver transplantation. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:1083–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Finlay D.E., Foshager M.C., Longley D.G., Letourneu J.G. Ischemic injury to the fetus after maternal liver transplantation. J Ultasound Med. 1994;13:145–148. doi: 10.7863/jum.1994.13.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Armenti V.T., Radomski J.S., Moritz M.J. Report from National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry (NTPR): outcomes of pregnancy after transplantation. Clin Transpl. 2005:69–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nagy S., Bush M.C., Berkowitz R., Fishbein T.M., Gomez- Lobo V. Pregnancy outcome in liver transplant recipients. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:121–128. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Murthy S.K., Heathcote E.J., Nguyen G.C. Impact of cirrhosis and liver transplant on maternal health during labor and delivery. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2009;7:1367–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sifontis N.M., Coscia L.A., Constantinescu S., Lavelanet A.F., Mortiz M.J., Armenti V.T. Pregnancy outcomes in solid organ transplant recipients with exposure to Mycophenolate mofetil or sirolimus. Transplantation. 2006;82:1698–1702. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000252683.74584.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coffin C.S., Shaheen A.A., Burak K.W. Pregnancy outcomes among liver transplant recipients in the United States: a nationwide case-control analysis. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:56–63. doi: 10.1002/lt.21906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Su G.G., Pan K.H., Zhao N.F., Fang S.H., Xang D.H., Zhou Y. Efficacy and safety of lamuvidine treatment for chronic hepatitis B in pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:910–912. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i6.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]