Abstract

CONTEXT

Young Latinos in the United States are at high risk for STDs and are less likely than other youth to use condoms. To our knowledge, no studies have examined the relationship between sexual values and condom negotiation strategies among young Latinos.

METHODS

Cross-sectional data collected in 2003–2006 from 571 Latino women and men aged 16–22 in the San Francisco Bay Area were used to examine associations between sexual values (e.g., considering sexual talk disrespectful or female virginity important) and use of strategies to engender or avoid condom use. Linear regression analyses were used to identify such associations while adjusting for potential covariates and gender interactions.

RESULTS

Among women, sexual comfort and comfort with sexual communication were positively associated with frequency of direct communication to foster condom use; the importance of premarital virginity and levels of sexual self-acceptance was positively associated with expressing dislike of condoms to avoid using them; and levels of sexual self-acceptance were negatively associated with expressing dislike of condoms to avoid using them. Moreover, the degrees to which women considered sexual talk disrespectful and female virginity important were positively associated with the frequency with which they shared risk information as a condom use strategy. Among both sexes, the importance that respondents placed on premarital female virginity was negatively associated with use of direct communication strategies.

CONCLUSION

Researchers designing interventions to influence Latino youths’ sexual decision making and behaviors should consider including program components that address sexual values.

Adolescents and young adults represent 25% of the sexually active population in the United States, yet account for about half of all diagnosed STDs.1 Latino youth in the United States are at high risk for STDs; compared with non-Latino whites, Latino adolescents have twice the risk of contracting gonorrhea and chlamydia, and four times the risk of contracting syphilis and HIV.1,2 By early adulthood, Latinos are more than four times as likely as their white counterparts to receive an AIDS diagnosis.2 Despite these disparities, research on contextual characteristics that are associated with inconsistent condom use and poor sexual health among Latino youth is scarce, and few STD interventions focus specifically on Latino adolescents and young adults.3

Use of male condoms reduces STD risk, but sexually active young Latinos are less likely than youth from other ethnic groups to use condoms. According to the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, in 2011, 42% of sexually active Latino youth reported not having used a condom during last intercourse, compared with 41% of whites and 35% of blacks.4 In fact, since the inception of the surveillance system in 1991, Latino youth have consistently reported lower levels of condom use than have their counterparts in other ethnic groups. These data raise important public health concerns, particularly because Latinos are the fastest growing ethnic minority group in the United States and are expected to constitute about 30% of the population by 2050.5

A growing body of research suggests that culture shapes youths’ beliefs about sexuality and sexual behaviors.6–10 Specific cultural values regarding sexuality that are prevalent among Latinos—such as valuing female virginity before marriage, avoiding sexual discussion within a relationship and giving fulfillment of men’s sexual desires precedence over fulfillment of women’s3,11–15—have implications for condom use among Latino youth.3,15 However, it is unclear whether these values are associated with condom-related behaviors, such as negotiation strategies with partners, that may be associated with actual condom use. In this article, we examine whether Latino youths’ sexual values are associated with the condom negotiation strategies they employ within their relationships. Although similar associations may also be applicable to other racial and ethnic groups, a focus on Latinos is important, given the high levels of inconsistent condom use in this population and the dearth of research conducted among Latino youth.

ACCULTURATION AND SEXUAL VALUES

Most studies examining culture and condom-related behaviors among Latino youth in the United States have used measures of acculturation to examine cultural shifts in sexual values. Low acculturation levels have been linked to low levels of condom use and condom use efficacy, and to high rates of unplanned pregnancy.16–19 Although these studies are important in establishing associations between culture and sexual risk, they provide limited insight into why these associations exist and, therefore, cannot definitively identify mechanisms or targets for intervention. Furthermore, commonly used measures of acculturation either are too broad (i.e., they include multiple acculturation domains) or depend on proxy measures (e.g., language use, country of origin). In contrast, sexual norms and values, such as those concerning female virginity and sexual communication, are specific and arguably more closely related to the sexual behaviors of Latino youth (including risk behaviors, such as inconsistent condom use) than are other measures of acculturation.14,15,20,21

As a result, research on condom use among Latinos is moving away from using general acculturation measures and toward examining cultural norms and values that are specific to sexuality.12,15 Nevertheless, we are aware of only one culturally based and empirically tested intervention that has integrated sexual values in a program targeting young Latinos’ sexual health behaviors.3,13 The program, Cuidate!, showed promising benefits with Spanish-speaking youth in a randomized controlled trial, but no improvement in English-speaking youths’ condom use behaviors.3 Thus, a deeper understanding of whether variations in sexual values are associated with condom use behaviors among linguistically acculturated youth is warranted.

One important way in which sexual values may shape condom use is by influencing the condom negotiation strategies that youth employ within sexual relationships. Such strategies are strong predictors of condom use.22 Research with ethnically diverse samples of young adults has identified commonly used condom negotiation strategies that rely on verbal communication, such as sharing information on STD risk to encourage condom use, as well as on nonverbal approaches, such as seducing one’s partner or ignoring the presence of condoms to avoid using them.23–27 Among Latinos, traditional cultural norms maintain that it is inappropriate for men and women to communicate about sex, even within a sexual relationship.17,28,29 Thus, discomfort with sexual communication among young Latinos may be associated with condom negotiation strategies that lead to inconsistent condom use.

To our knowledge, only one study has examined whether condom negotiation strategies used by Latino youth are linked to actual condom use.30 It found that Latino adolescents and young adults engaged in multiple strategies—both verbal and nonverbal—to foster or avoid condom use. Citing risk information and direct verbal and nonverbal communication were effective strategies for encouraging condom use, even when youth perceived that their partner did not want to use condoms. Findings also showed that seduction was an effective condom avoidance strategy, but only for women. Unexpectedly, expressing dislike of condoms was associated with higher levels of condom use; the relationship was particularly strong among young men. Although this research represents an important step toward understanding whether negotiation strategies are associated with condom use, no studies have looked further upstream to determine whether sexual values, such as comfort with sexual communication or beliefs about virginity, are associated with negotiation strategies.

The primary purpose of this study was to determine whether certain condom negotiation strategies that have been linked to actual condom use are associated with Latino youths’ sexual values. Low acculturation levels are related to less consistent condom use among Latinos;9 therefore, we hypothesized that youth who endorsed traditional sexual values would engage in condom avoidance strategies more often than other youth, and that those who endorsed less traditional sexual values would report higher levels of condom use strategies. We also hypothesized that associations would be stronger for young women than for young men, given that the sexual values we examined reflect culturally driven, gender-based expectations of sexuality—such as the importance of women’s abstaining from sex before marriage and of men’s sexual needs being satisfied. Thus, we examined gender as a potential effect modifier.

METHODS

Participants and Survey Procedure

Data originated from a cross-sectional study, conducted in 2003–2006, of relationship power and condom use among Latino youth in the San Francisco Bay Area.14,15,30 Youth were eligible if they were of Mexican, Nicaraguan or Salvadoran origin (these were the three largest Latino ethnic groups in the area); were aged 16–22; and currently had a partner with whom they had had sex in the past six months.

We recruited participants from a large HMO and community health clinics in San Francisco. To recruit participants from the HMO, we used membership lists to identify households in which a Latino youth aged 16–22 lived and sent an introductory letter describing the study (letters for participants younger than 18 were addressed to their parents). Interviewers subsequently telephoned the families, obtained parental permission to speak with the adolescent if he or she was a minor, and conducted a screening interview with the youth to determine eligibility. Youth recruited at clinics were screened for eligibility while waiting for appointments. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and parental consent was obtained for minors who were not seeking confidential health services. Seventy-one percent of eligible youth participated in the study.

Participants completed one-hour, computer-assisted individual interviews conducted in person at the HMO or community clinics by trained bilingual young adults, who were matched to participants by gender. Youth received $50 as compensation for their time. The portion of each interview that covered sensitive topics was self-administered, with interviewer assistance, to minimize respondent bias; the remainder was administered by the interviewer. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the HMO and the University of California, San Francisco.

Measures

Sexual values

Six sexual values scales were developed for this study using information obtained from focus groups and qualitative interviews with Latino youth. Systematic assessment of the scales’ psychometric properties indicated that the scales are reliable and valid; details are described elsewhere.14 Unless otherwise noted, the final score for each scale is the average of the scores for its component items. Respondents’ views of the importance of female virginity were assessed using a three-item scale (e.g., “Do you think it’s okay for girls to have sex before they are in a serious relationship?”). Response options ranged from 1 to 4 (“definitely no” to “definitely yes”; Cronbach’s alpha=0.64). The importance that respondents placed on satisfaction of sexual needs was assessed using a four-item measure. Two items addressed men’s sexual needs (e.g., “Do you think if a guy gets sexually excited, the girl should satisfy his sexual needs?”), and two addressed women’s sexual needs (e.g., “Do you think if a girl gets sexually excited, the guy should satisfy her sexual needs?”). Both males and females answered all four items. Response options ranged from 1 to 4 (“definitely no” to “definitely yes”; Cronbach’s alpha=0.72). Another four-item scale assessed whether respondents considered it disrespectful to discuss certain sexual topics at various stages of a relationship (e.g., “Is it okay for a girl to talk about sex with a guy …when they know each other but aren’t dating?”). Response options were yes or no; negative responses were given a value of 1 and summed to yield a score ranging from 0 to 4 (Cronbach’s alpha=0.69). Thus, youth with high scores on this scale considered sexual talk disrespectful. Comfort with sexual communication was assessed using eight items about talking to one’s current partner (e.g., “How would you feel talking about what you don’t like during sex?”). The four possible responses ranged from 1 to 4 (“very uncomfortable” to “very comfortable”; Cronbach’s alpha=0.85). Sexual comfort was measured using a 10-item scale (e.g., “How would you feel having sex with the lights on?”); response options ranged from 1 to 4 (“very uncomfortable” to “very comfortable”; Cronbach’s alpha=0.89). Finally, sexual self-acceptance was assessed using 10 items (e.g., “Do you think it’s okay for you to have sex?”); possible responses ranged from 1 to 5 (“not at all” to “very much”; Cronbach’s alpha=0.72).

Condom negotiation strategies

Using scales developed for this study from information obtained from focus groups and qualitative interviews, we assessed four condom negotiation strategies. Participants who reported a time in the last month when they had wanted to use condoms responded to items that reflected two condom use strategies. Sharing of risk information was assessed using a scale consisting of seven items (e.g., whether the youth had told his or her partner that “there are a lot of STDs out there”; Cronbach’s alpha=0.85), and use of direct verbal and nonverbal communication was measured using six items (e.g., whether the respondent had “offer[ed] to put the condom on”; Cronbach’s alpha=0.85). For all items, respondents indicated the number of times in the past month they had done the specified behavior; response options ranged from 0 (“never”) to 3 (“more than a few times”).

In addition, youth who reported a time in the last month when they had not wanted to use condoms responded to items that reflected two condom avoidance strategies. Expressing dislike of condoms was assessed using five items (e.g., whether the youth had told his or her partner “that it feels better without a condom”; Cronbach’s alpha=0.61), and use of seduction was assessed using two items (e.g., whether the respondent had tried to get his or her “partner too turned on to think about condoms”; Cronbach’s alpha=0.67).

Youth who had sometimes wanted and sometimes not wanted to use a condom in the last month completed both sets of items. All measures had good psychometric properties; the scales and their development are described in detail elsewhere.30

Covariates

Participant gender, age, nativity (born in versus outside the United States), country of heritage (Mexico, Nicaragua or El Salvador), education (in years), duration of relationship (in months) and linguistic acculturation were examined as potential covariates. Linguistic acculturation was assessed using the five items of the English Language Use subscale of the Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (e.g., “How often do you speak English”);31 response categories ranged from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“always”), and responses were averaged to form the scale (Cronbach’s alpha=0.87).

Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 15.0. We performed descriptive analyses for the full sample, as well as for males and females separately. To determine which covariates to include in final multivariate models, we calculated bivariate correlations of covariates and sexual values with condom negotiation strategies. Multiple linear regression analyses that adjusted for key covariates were used to examine associations between sexual values and condom negotiation strategies. Because of possible collinearity between the sexual values, the combination of each sexual value and each condom negotiation strategy was examined separately. In the multiple regression analyses, we first regressed the condom negotiation strategy on the covariates; we then added the sexual value, adjusting for all covariates; and finally, we added a term for the interaction between the sexual value and gender, adjusting for all variables in the previous two steps. To examine statistically significant interactions between sexual values and gender, we centered sexual values (subtracted each score from the mean score) and plotted slopes within each gender.32

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

A total of 694 Latino youth aged 16–22 participated in the research; 61% were female. The majority (93%) completed the interview in English. On average, participants had completed 12 years of education and had been in their current sexual relationship for 21 months.

During the past month, 395 participants had wanted to use a condom, 298 had wanted to avoid using a condom and 120 had wanted to do both. Only 97 reported neither wanting to use nor wanting to avoid using a condom; these participants were not asked about condom negotiation strategies and were excluded from subsequent analyses, as were 26 who reported not having sex in the past month. Thus, the analytic sample comprised 571 participants (82% of the original sample). Nearly all participants (95%) who had wanted to use a condom during the past month had employed a condom use strategy. Similarly, of those who had wanted to avoid condom use, the vast majority (91%) had used a condom avoidance strategy.

On average, males in the final sample were slightly older than their female counterparts, and women used English to a slightly greater degree than men did (Table 1). Seventy-seven percent of participants had been born in the United States; the remaining 23% had immigrated at an average age of seven (not shown). Men valued the satisfaction of sexual needs more than women did (mean score, 2.3 vs. 1.7), and also reported higher levels of sexual comfort (3.3 vs. 3.0) and sexual self-acceptance (4.6 vs. 4.3). Women valued female premarital virginity more than men did (2.4 vs. 2.2). No gender differences were apparent on the scales for comfort with sexual communication and considering sexual talk disrespectful; notably, most youth scored either 0 or 1 on the latter scale, resulting in a low mean score (not shown).

TABLE 1.

Selected characteristics of Latino youth participating in a study of sexual values and condom negotiation strategies, by gender, San Francisco Bay Area, 2003–2006

| Characteristic | All (N=571) | Males (N=232) | Females (N=339) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age (range, 16–22) | 18.44 (1.62) | 18.64 (1.44)* | 18.30 (1.71) |

| English language use (range, 1–5) | 3.81 (0.87) | 3.72 (0.91)* | 3.88 (0.84) |

| % U.S.-born | 76.7 | 78.4 | 75.4 |

| Sexual values | |||

| Disrespectfulness of sexual talk (range, 0–4) | 0.48 (0.73) | 0.46 (0.75) | 0.49 (0.72) |

| Importance of satisfaction of sexual needs (range, 1–4) | 1.93 (0.66) | 2.25 (0.64)*** | 1.70 (0.58) |

| Importance of female virginity (range, 1–4) | 2.31 (0.67) | 2.16 (0.60)*** | 2.40 (0.69) |

| Comfort with sexual communication (range, 1–4) | 3.40 (0.46) | 3.43 (0.47) | 3.37 (0.45) |

| Sexual comfort (range, 1–4) | 3.11 (0.55) | 3.30 (0.52)*** | 2.98 (0.54) |

| Sexual self-acceptance (range, 1–5) | 4.38 (0.69) | 4.56 (0.59)*** | 4.26 (0.72) |

| Condom use strategies | |||

| Sharing risk information (range, 0–3) | 1.00 (0.78) | 0.95 (0.79) | 1.04 (0.77) |

| Direct communication (range, 0–3) | 1.00 (0.83) | 1.43 (0.80)*** | 0.71 (0.71) |

| Condom avoidance strategies | |||

| Expressing dislike of condoms (range, 0–3) | 0.63 (0.55) | 0.60 (0.54) | 0.66 (0.56) |

| Seduction (range, 0–3) | 0.25 (0.57) | 0.22 (0.51) | 0.27 (0.61) |

p<.05.

p<.001.

Notes: All values are means (with standard deviations), except for percentage U.S.-born. Sample sizes varied for measures of condom use strategies and condom avoidance strategies.

Men used direct communication as a condom use strategy more often than women did (mean score, 1.4 vs 0.7). However, men and women did not differ in the scores for the remaining use and avoidance strategies.

Bivariate Results

Age, gender and nativity were each correlated with at least one condom use or condom avoidance strategy (Table 2). Age was positively correlated with use of direct communication (coefficient, 0.13) and negatively correlated with expression of dislike of condoms (−0.12). Being female was negatively associated with use of direct communication (−0.43), and having been born in the United States was negatively correlated with expression of dislike of condoms (−0.13). Thus, we included these three variables as covariates in our multivariate models. We also included use of English language as a covariate, even though it was not directly associated with condom use strategies, because we were conceptually interested in whether associations between sexual values and condom negotiation strategies persist when a linguistic measure of acculturation is included in models.

TABLE 2.

Coefficients from bivariate analyses assessing correlations between selected characteristics and condom negotiation strategies

| Characteristic | Condom use (N=370) | Condom avoidance (N=284) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Sharing risk information | Direct communication | Expressing dislike of condoms | Seduction | |

| Demographic | ||||

| Age | −0.04 | 0.13* | −0.12* | −0.08 |

| English language use | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Female | 0.07 | −0.43* | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| U.S.-born | −0.07 | 0.01 | −0.13* | −0.07 |

| Sexual values | ||||

| Disrespectfulness of sexual talk | 0.07 | −0.13* | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| Importance of satisfaction of sexual needs | 0.03 | 0.17** | 0.12* | 0.03 |

| Importance of female virginity | 0.11* | −0.21*** | 0.18** | 0.07 |

| Comfort with sexual communication | −0.10 | 0.10 | −0.12* | −0.10 |

| Sexual comfort | −0.03 | 0.24*** | −0.09 | −0.01 |

| Sexual self-acceptance | −0.05 | 0.20*** | −0.13* | −0.19** |

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

Significant correlations were also apparent between sexual values and condom negotiation strategies, particularly direct communication (for condom use) and expressed dislike of condoms (for condom avoidance). Associations were generally in expected directions. Considering sexual talk disrespectful within relationships and valuing female virginity were negatively correlated with use of direct communication as a condom use strategy (coefficients, −0.13 and −0.21, respectively), whereas the importance of satisfying sexual needs and levels of sexual comfort and sexual self-acceptance were positively correlated with such communication (0.17, 0.24 and 0.20, respectively). The importance of sexual satisfaction and of female virginity were positively correlated with expressing dislike of condoms as a condom avoidance strategy (0.12 and 0.18); comfort with sexual communication and sexual self-acceptance were negatively correlated with this approach (−0.12 and −0.13). Finally, the importance of female virginity was positively correlated with sharing risk information as a condom use strategy (0.11), while sexual self-acceptance was negatively correlated with using seduction as a condom avoidance strategy (−0.19).

Multivariate Results

Condom use strategies

Multivariate analyses revealed two main associations between sexual values and condom use strategies (Table 3). The importance that youth placed on female virginity was negatively associated with the use of direct communication (coefficient, −0.12). The other association, which was between sexual comfort and use of direct communication, was modified by gender (i.e., the interaction term was statistically significant); therefore the main effect should not be interpreted.32

TABLE 3.

Coefficients from multivariate regression analyses examining associations between selected characteristics and condom negotiation strategies

| Characteristic | Condom use | Condom avoidance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Sharing risk information | Direct communication | Expressing dislike of condoms | Seduction | |

| Demographic | ||||

| Age | −0.05 | 0.10* | −0.12 | −0.06 |

| English language use | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Female | 0.06 | −0.43*** | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| U.S.-born | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.16* | −0.10 |

| Sexual values | ||||

| Disrespectfulness of sexual talk | 0.05 | −0.10 | 0.11 | 0.05 |

| Importance of satisfaction of sexual needs | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.18** | 0.08 |

| Importance of female virginity | 0.09 | −0.12* | 0.16** | 0.06 |

| Comfort with sexual communication | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.11 | −0.09 |

| Sexual comfort | −0.01 | 0.12* | −0.07 | 0.01 |

| Sexual self-acceptance | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.13* | −0.18* |

| Interactions | ||||

| Female x disrespectfulness of sexual talk | 0.48** | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| Female x importance of satisfaction of sexual needs | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.03 | −0.35 |

| Female x importance of female virginity | 0.42* | 0.31 | 0.61** | 0.31 |

| Female x comfort with sexual communication | 0.05 | 0.32* | −0.06 | 0.21 |

| Female x sexual comfort | −0.01 | 0.39* | −0.01 | 0.13 |

| Female x sexual self-acceptance | −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.44* | −0.38 |

| Total R2 (range) | 0.01–0.04* | 0.20–0.22*** | 0.04–0.09*** | 0.02–0.06** |

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

Notes: Each sexual value and its interaction term were included in a separate model for each condom negotiation strategy (24 models total). Analyses of sexual values included all covariates; analyses of interactions included covariates and sexual values.

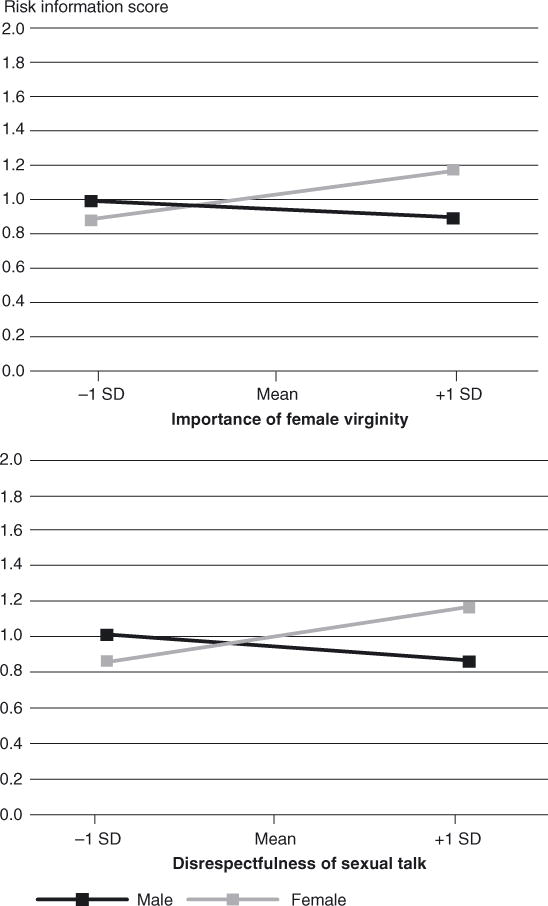

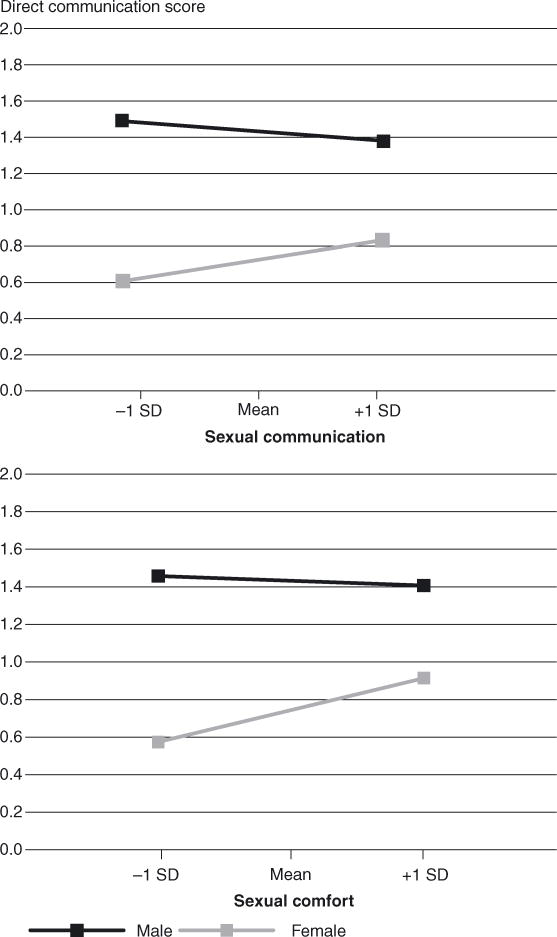

Four interactions between sexual values and gender were significant for condom use strategies. The more that young women (but not young men) believed that sexual talk is disrespectful, the more often they used risk information (coefficient, 0.48) and the higher the value the placed on female virginity (0.42—Table 3 and Figure 1). In addition, the frequency of women’s (but not men’s) use of direct communication was positively associated with their level of comfort with sexual communication (0.32) and their level of sexual comfort (0.39—Table 3 and Figure 2). Overall, men engaged in direct communication condom use strategies more often than women did, regardless of their levels of sexual comfort and comfort with sexual communication. Notably, our final model explained 20–22% of the variance in frequency of direct communication as a condom use strategy.

FIGURE 1.

Use of risk information to obtain condom use, as predicted by interaction between gender and selected sexual values

Note: SD=Standard deviation.

FIGURE 2.

Use of direct communication to obtain condom use, as predicted by interaction between gender and selected sexual values

Note: SD=Standard deviation.

Condom avoidance strategies

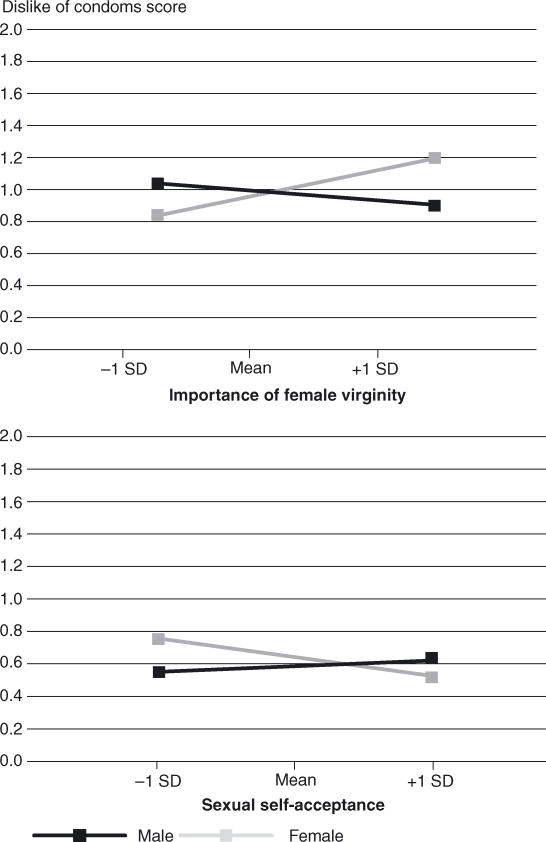

Two significant main effects without interactions emerged among participants who wanted to avoid condom use (Table 3). The belief that satisfaction of sexual needs is important was positively associated with expressed dislike of condoms (coefficient, 0.18), and sexual self-acceptance was negatively associated with use of seduction (−0.18).

In addition, we found two significant interactions (Table 3 and Figure 3). The greater importance young women (but not young men) placed on female virginity, the more often they expressed dislike of condoms (coefficient, 0.61). Similarly, the greater the level of sexual self-acceptance that young women (but not young men) had, the less often they expressed dislike of condoms (−0.44).

FIGURE 3.

Expression of dislike of condoms, as predicted by interaction between gender and selectd sexual values

Note: SD=Standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

Although the failure to address young Latinos’ cultural values may undermine the effectiveness of efforts to reduce the high levels of unprotected sex among such youth,21,26,33–37 little research has focused on whether acculturation—and in particular, sexual values—is associated with Latino youths’ sexual decision making.10–12,15,26 We hypothesized that traditional sexual values would be associated with less frequent utilization of condom use strategies and with more frequent use of condom avoidance strategies. Our findings provide general support for this claim. In addition, gender played a key role in determining whether sexual values were associated with certain condom negotiation strategies.

Young women who were more comfortable sexually and those who reported greater comfort with sexual communication used direct communication to a greater degree than did women who were less comfortable in those areas, whereas young men tended to use direct communication strategies in general more frequently than women did, irrespective of their sexual values in those domains. These findings are important because direct communication is a strategy that many comprehensive sex education programs recommend to encourage a partner to use condoms (e.g., the Communication Skills Condom Use Program).38 Research with ethnically diverse groups of college students found that use of assertive and direct negotiation strategies was positively associated with frequency of condom use.27 If such findings indicate a causal relationship, then an enhanced focus on increasing young Latina women’s sexual comfort and their comfort with sexual communication may be important when helping these women develop direct sexual communication skills. Moreover, the effectiveness of teaching direct communication strategies may differ depending on participants’ gender, cultural background and sexual values.26,39 Future research should empirically test whether efforts to increase sexual communication and comfort among young Latina women lead to more frequent use of direct communication strategies and, ultimately, to higher levels of condom use.

The importance of young men in supporting Latina women’s use of direct communication strategies also needs to be examined. Research suggests that partner characteristics are strongly associated with how young black men react to women’s condom negotiation strategies, and that no one negotiation strategy seems to be universally effective.40 These findings speak to the importance of relationship dynamics and partner support for condom use. Research with young Asian women has shown that their sexual communication varies by partner characteristics, including age and ethnicity.39 Similarly, young Latinos’ perceptions of partners’ desires to use condoms appear to be associated with whether condom negotiation strategies lead to actual condom use.30,41 It is critical to extend this body of research to better understand how young men respond to their female partners’ condom negotiation attempts and how they may reciprocally influence these strategies and sexual decision making. Such an examination would further our understanding of sexual relationship dynamics, which are imperative to consider (alongside individual-level examinations of condom negotiation) in designing future prevention efforts.

Our findings also showed that young Latinos’ notions about female virginity were associated with their condom negotiation strategies. The importance that both young men and young women placed on premarital female virginity was negatively associated with their use of direct communication about condom use. This draws attention to partner characteristics that are likely associated with less direct communication. For example, if both a young man and a young woman in a sexual partnership highly value premarital virginity, yet engage in sex before marriage, they may be less likely than other couples to engage in direct communication (verbal or nonverbal) about condom use, even when they want to use condoms.

Moreover, we found that women who highly valued virginity and those who strongly believed that sexual talk is disrespectful used risk information to motivate their partner to use a condom more often than did women who placed less importance on premarital virginity or felt less strongly that sexual talk is disrespectful. Members of some non-European ethnic groups (e.g., Asians) tend to use indirect strategies to negotiate condom use,26,39 and research suggests that citing risk information is an effective method for Latino couples to achieve condom use within sexual partnerships, even when youth perceive their partners as not wanting to use condoms.30 Therefore, interventions designed to enhance youths’ condom negotiation skills may be more successful if they provide strategies that youth are comfortable using and that are consistent with their sexual values. For young Latina women who adhere to traditional sexual values, such as attaching importance to virginity, sharing risk information may be a more comfortable approach than direct communication for conveying the importance of condoms. Randomized controlled trials could be used to test whether these approaches (as well as those that seek to increase sexual comfort and communication and promote use of direct strategies) are successful condom use strategies for certain individuals.

Almost half of the youth in our sample reported having wanted to avoid using condoms in the past month; of those, more than 90% had used at least one condom avoidance strategy during that time. Given past research documenting that condom use rates among Latinos were positively associated with level of acculturation,9 we expected that those who endorsed traditional sexual values would engage in condom avoidance strategies more often than other youth. This hypothesis was supported by the finding that young people with lower levels of sexual self-acceptance used seduction to avoid condom use more often than did those with higher levels of sexual self-acceptance. We had expected that this might be the case for young women, given traditional gender roles; however, we were surprised to find that this was true for men as well. Moreover, women who highly valued premarital virginity or had lower levels of self-acceptance were more likely than those who did not to have expressed dislike of condoms. Expressing dislike of condoms may reflect a young woman’s desire to provide pleasure to her male partner. Young men who consider sexual satisfaction important and young men and women who believe that condoms reduce sexual pleasure are less likely than others to use condoms consistently.15,42,43 Therefore, young women who subscribe to traditional gender norms may avoid condom use because they prioritize sexually satisfying their male partners over protecting their own sexual health.

Our findings must be interpreted cautiously, however. Decision making takes place within the context of partnerships whose particular dynamics depend on the characteristics that each partner brings to and elicits within the relationship. Within these contexts, the whole does not necessarily equal the sum of its parts. Research is needed that focuses on couples and on the interplay between their respective—and potentially differing—sexual values and condom negotiation strategies. Such research would provide greater insight into decision making within the contexts of youths’ relationships.

Strengths and Limitations

Notable strengths of this study include the large sample size and the in-depth data we collected on cultural measures, particularly given the sensitive nature of the questions asked. However, because the vast majority of the study’s participants completed the interviews in English, the study may not be generalizable to non–English speaking populations. In a sample with a wider range of linguistic acculturation, sexual values may exhibit different associations with condom negotiation strategies. Our sample was predominantly urban, further limiting generalizability. Because data were cross-sectional, we could not establish the temporal order of the variables. Prospective research is needed that assesses youths’ sexual values prior to the initiation of sexual activity and tracks the emergence of sexual behaviors and condom use over time. Moreover, although we suspect that sexual values influenced condom negotiation strategies, unmeasured variables related to youths’ relationships may underlie both their sexual values and their strategies to use or avoid condoms.

Finally, we did not examine whether condom negotiation strategies mediate associations between sexual values and actual condom use. Our previous analysis using these data revealed complex associations between condom negotiation strategies and condom use that were moderated by participant gender, as well as by individuals’ perceptions of their partners’ desires to use condoms.30 Testing complex mediation pathways from sexual values to condom use was beyond the scope of the current investigation, but remains an important line of inquiry for future studies.

Future Directions and Implications

To our knowledge, only one culturally based intervention to improve young Latinos’ sexual health behaviors has taken sexual values into account, and this program showed limited efficacy in improving the consistency of condom use among English-speaking youth.3,12,13 Condom negotiation strategies among Latino youth are understudied and represent an important outcome of interest, given the documented associations of such strategies with actual condom use among Latinos and other ethnic groups.22,27,30,44 Our findings highlight some key areas on which investigators may wish to focus when conducting future research aimed at increasing condom use among English-speaking Latino youth. Researchers should consider the value of adding specific program components that address sexual values to assess their influence on Latino youths’ sexual decision making and behaviors. Such efforts to improve preventive intervention approaches have the potential to advance our understanding of the context within which condom-related behaviors occur. Only through a deeper inquiry into these complex and nuanced processes can we begin to develop stronger programmatic components to improve condom use behaviors among young Latinos.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01AI49146 from the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, and grant K12HD052163–13 from the Office of Research on Women’s Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors thank Northern California Kaiser Permanente’s Division of Research for providing access to members of Kaiser Permanente.

Contributor Information

Julianna Deardorff, Email: jdeardorff@berkeley.edu, Division of Community Health and Human Behavior, School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley.

Jeanne M. Tschann, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine; University of California, San Francisco.

Elena Flores, Department of Counseling Psychology, School of Education, University of San Francisco.

Cynthia L. de Groat, Department of Health Psychology, University of California, San Francisco.

Julia R. Steinberg, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine; University of California, San Francisco.

Emily J. Ozer, Division of Community Health and Human Behavior, School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2011. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. HIV Surveillance Report, 2010. Vol. 22. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [accessed Feb. 10, 2013]. < http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010report/pdf/2010_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_22.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villarruel AM, Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS. A randomized controlled trial testing an HIV prevention intervention for Latino youth. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160(8):772–777. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(SS-4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Census Bureau. [accessed Jan. 5, 2011];2008 national population projections. 2008 < http://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2008.html>.

- 6.Bowleg L, et al. ‘What does it take to be a man? What is a real man? ’: Ideologies of masculinity and HIV sexual risk among Black heterosexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011;13(5):545–559. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.556201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fasula AM, Miller KS, Wiener J. The sexual double standard in African American adolescent women’s sexual risk reduction socialization. Women & Health. 2007;46(2–3):3–21. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harper GW, et al. The role of close friends in African American adolescents’ dating and sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2004;41(4):351–362. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afable-Munsuz A, Brindis CD. Acculturation and the sexual and reproductive health of Latino youth in the United States: a literature review. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38(4):208–219. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.208.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raffaelli M, Kang H, Guarini T. Exploring the immigrant paradox in adolescent sexuality: an ecological perspective. In: García Coll C, Marks A., editors. The Immigrant Paradox in Children and Adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 109–134. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raffaelli M, Iturbide MI. Sexuality and sexual risk behaviors among Latino adolescents and young adults. In: Villarruel FA, et al., editors. Handbook of US Latino Psychology: Developmental and Community-Based Perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. pp. 399–414. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villarruel AM, et al. Predictors of sexual intercourse and condom use intentions among Spanish-dominant Latino youth: a test of the planned behavior theory. Nursing Research. 2004;53(3):172–181. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villarruel AM, Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB., 3rd Designing a culturally based intervention to reduce HIV sexual risk for Latino adolescents. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2005;16(2):23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deardorff J, Tschann JM, Flores E. Sexual values among Latino youth: measurement development using a culturally based approach. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(2):138–146. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deardorff J, et al. Sexual values and risky sexual behaviors among Latino youths. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;42(1):23–32. doi: 10.1363/4202310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ford K, Norris AE. Urban Hispanic adolescents and young adults: relationship of acculturation to sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 1993;30(4):316–323. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marín BV, et al. Condom use in unmarried Latino men: a test of cultural constructs. Health Psychology. 1997;16(5):458–467. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.5.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marín BV, et al. Acculturation and gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: Hispanic vs non-Hispanic white unmarried adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83(12):1759–1761. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.12.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brindis CD, et al. The associations between immigrant status and risk-behavior patterns in Latino adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1995;17(2):99–105. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)00101-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raffaelli M, Suarez-Al-Adam M. Reconsidering the HIV/AIDS prevention needs of Latino women in the United States. In: Roth NL, Fuller LK, editors. Women and AIDS: Negotiating Safer Practices, Care, and Representation. Binghamton, NY: Harrington Park Press; 1998. pp. 7–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Betancourt H, Lopez SR. The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American Psychologist. 1993;48(6):629–637. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holland KJ, French SE. Condom negotiation strategy use and effectiveness among college students. Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49(5):443–453. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.568128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bird ST, et al. Getting your partner to use condoms: interviews with men and women at risk of HIV/STDs. Journal of Sex Research. 2001;38(3):233–240. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edgar T, et al. Strategic sexual communication: condom use resistance and response. Health Communication. 1992;4(2):83–104. [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Bro SC, Campbell SM, Peplau LA. Influencing a partner to use a condom: a college student perspective. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1994;18(2):165–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1994.tb00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam AG, et al. What really works? An exploratory study of condom negotiation strategies. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16(2):160–171. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.2.160.29396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.French SE, Holland KJ. Condom negotiation strategies as a mediator of the relationship between self-efficacy and condom use. Journal of Sex Research. 2013;50(1):48–59. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.626907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marín BV. HIV prevention in the Hispanic community: sex, culture, and empowerment. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2003;14(3):186–192. doi: 10.1177/1043659603014003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marston C. Gendered communication among young people in Mexico: implications for sexual health interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59(3):445–456. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tschann JM, et al. Condom negotiation strategies and actual condom use among Latino youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47(3):254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marin G, Gamba RJ. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (BAS) Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18(3):297–316. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vexler E, Suellentrop K, editors. Bridging Two Worlds: How Teen Pregnancy Prevention Programs Can Better Serve Latino Youth. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Guidelines Task Force and Hispanic/Latino Adaptation Task Force, . Guidelines for Comprehensive Sexuality Education for Hispanic/Latino Youth. New York: Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phinney JS, Flores J. “Unpackaging” acculturation: aspects of acculturation as predictors of traditional sex role attitudes. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2002;33(3):320–331. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cauce AM. Examining culture within a quantitative empirical research framework. Human Development. 2002;45(4):294–298. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laub C, et al. Targeting “risky” gender ideologies: constructing a community-driven, theory-based HIV prevention intervention for youth. Health Education & Behavior. 1999;26(2):185–199. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanderson CA, Jemmott JB., 3rd Moderation and mediation of HIV-prevention interventions: relationship status, intentions, and condom use among college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1996;26(23):2076–2099. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lam AG, Barnhart JE. It takes two: the role of partner ethnicity and age characteristics on condom negotiations of heterosexual Chinese and Filipina American college women. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(1):68–80. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Otto-Salaj LL, et al. Reactions of heterosexual African American men to women’s condom negotiation strategies. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;47(6):539–551. doi: 10.1080/00224490903216763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fortenberry JD. Fate, desire, and the centrality of the relationship to adolescent condom use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47(3):219–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jemmott JB, 3rd, et al. Self-efficacy, hedonistic expectancies, and condom-use intentions among inner-city black adolescent women: a social cognitive approach to AIDS risk behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1992;13(6):512–519. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Villarruel AM. Cultural influences on the sexual attitudes, beliefs, and norms of young Latina adolescents. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nurses. 1998;3(2):69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.1998.tb00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jemmott JB, 3rd, et al. Effectiveness of an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for adolescents when implemented by community-based organizations: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(4):720–726. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]