Abstract

Isotope labeling revolutionized NMR studies of small nucleic acids, but to extend this technology to larger RNAs requires site-specific labeling tools to expedite NMR structural and dynamics studies. Using enzymes from the pentose phosphate pathway, we couple chemically synthesized uracil nucleobase with specifically 13C-labeled ribose to synthesize both UTP and CTP with nearly quantitative yields. This chemo-enzymatic method affords a cost-effective preparation of labels that are unattainable by current methods. The methodology generates versatile 13C and 15N labeling patterns which, when employed with relaxation-optimized NMR spectroscopy, effectively mitigates problems of rapid relaxation that result in low resolution and sensitivity. The methodology is demonstrated with RNAs of various sizes, complexity, and importance: the exon splicing silencer 3 (27 nt), iron responsive element (29 nt), Pro-tRNA (76 nt), and HIV-1 core encapsidation signal (155 nt).

Keywords: RNA, NMR spectroscopy, Labeling, Structure, Dynamics

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) plays critical roles in essentially all forms of life including signaling, gene regulation, catalysis, and retroviral infection.[1–5] RNA partakes in such a broad range of functions because it can adopt intricate and pliable three-dimensional structures. However there is a dearth of structural dynamics information on RNA, even though RNA functions are dependent on structural dynamics.

The reasons for this paucity of structural information include conformational heterogeneity, uniform negative surface charge, and extensive chemical shift overlap and fast relaxation properties of the constituent nuclei (1H, 13C, 15N, 31P). These problems give rise to low resolution and sensitivity. The chemical shift overlap problem has been partially addressed by uniform labeling and fast relaxation by transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy (TROSY).[6–8] However, uniform labeling introduces direct one-bond and residual dipolar 13C-13C couplings that exacerbate resolution, sensitivity, and linewidth problems, and hinder accurate measurement of 13C relaxation parameters.[9]

To address the limitations of uniform labeling, five approaches are utilized to obtain site-specifically and isotopically labeled RNA. (i) Total chemical synthesis of nucleotides, followed by solid-phase synthesis of RNA using phosphoramidite chemistry. This method is powerful for incorporation of isotopes into RNA at any desired position, but it faces problems of regio- and stereo-selectivity during phosphoramidite synthesis, and low yields (<10 %) that drop significantly for larger oligonucleotides > 50 nt. [10–12] (ii) De novo biosynthesis of NTPs, followed by in vitro RNA transcription. This robust technique produces labeled nucleotides at significant yields (<60 %),[13] but comes at the cost of using ~18-23 enzymes, expensive precursor substrates, and inaccessibility to some labeling patterns: labeling the ribose C1′ and C5′ in the context of pyrimidine C4, C5, and C6 (readily done with our new method) requires 13C2-2,6-glucose that is not commercially available and 13C-labeled D/L-aspartic acid that is prohibitively costly. (iii) Phosphorylated biomass-produced NMPs used for in vitro RNA transcription. This method again provides useful labeled nucleotides; however, the overall yield is low per labeled input metabolite, and isotopic scrambling often leads to inadequate suppression of 13C-13C coupling.[7,14,15] (iv) Phosphorylated selective biomass-produced NMPs used for in vitro RNA transcription. Again this method overcomes the isotopic scrambling problem with adequate suppression of 13C-13C couplings; however, low overall yields remain an issue.[16–19] (v) Chemo-enzymatic synthesis of NTPs, followed by in vitro RNA transcription. This approach is potentially the most versatile method available. However until now, lack of commercially available selectively labeled ribose and base precursors has hampered the realization of its full potential.[20]

Here we combine an improved organic synthetic approach that selectively places labels in the pyrimidine nucleobase (either 15N1, 15N3, 13C2,13C4, 13C5, or 13C6 or any combination) and a very efficient enzymatic method to couple ribose with uracil to produce previously unattainable labeling patterns (Scheme 1) containing isolated two-spin systems in both the ribose and the nucleobase. We show that these labels are ideal for both structural and dynamic studies for large RNAs.

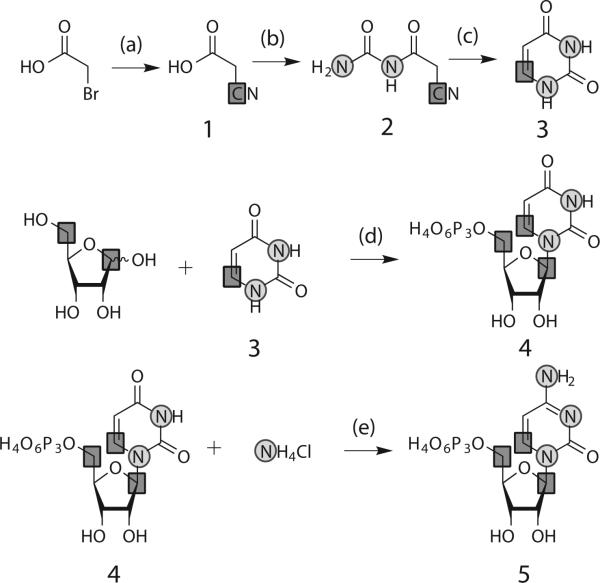

Scheme 1.

Chemical-enzymatic synthesis of UTP and CTP. aReagents and conditions: (a) sodium carbonate, pH 9, 3 h at 80 °C, 20 h at rt; (b) urea in acetic anhydride, 30 min at 90 °C, (c) 5 % Pd/BaSO4 in 50 % aqueous acetic acid, 36 h at rt; (d) ribokinase, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase, uridine phosphoribosyl transferase, nucleoside monophosphate kinase in sodium phosphate pH 7.5, 12 h at 37 °C; (e) cytidine triphosphate synthetase in Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 6 h at 37 °C. Squares: 13C; Circles: 15N.

Using the method of Santa Lucia and co-workers,[21] we synthesized 6-13C1-1,3-15-uracil, 3, using K13CN, bromoacetic acid and 15N2-urea (Scheme 1) with yields >82 %.[10] The identity of 3 was confirmed by NMR (SI-1).

To demonstrate the versatility of this approach, we coupled 1′,5′-13C2-D-ribose (Omicron Biochemicals, Southbend, IN) to 3 in enzymatic condensation reactions (Scheme 1) using the following three/four enzymes from the pentose phosphate pathway: Ribokinase (E.C. 2.7.1.15), phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase (E.C. 2.7.6.1); uridine phosphoribosyl transferase (E.C. 2.4.2.9); and CTP synthetase (E.C. 6.3.4.2).[6,22–27] All four enzymes were expressed and purified as described in our previous work.[28]

The in vitro one-pot, two-step synthesis of UTP, 4, was accomplished quickly, in high yields, and with extreme ease. First, UMP was synthesized from 1′,5′-13C2-D-ribose and 3 within 5 h (SI-2). This labeled UMP was readily converted to 4 in situ using nucleoside monophosphate kinase. The final yield of 4 was ~90% with respect to starting uracil (Supplementary methods). The identity of 4 was confirmed by HPLC and NMR (SI-2). From UTP, CTP, 5, was directly synthesized and purified (Scheme 1).[29] The yield for CTP from UTP was nearly quantitative after 6 hours (SI-3) and the recovery of isolated product after purification was nearly 90% with respect to UTP.

These site-specifically labeled nucleotides were then used for in vitro transcriptions of four RNAs of interest (Scheme 2): (i) exon splicing silencer 3 (ESS3, 27 nt) involved in inhibition of splicing through occlusion of the spliceosome assembly;[30] (ii) iron responsive element (IRE, 29 nt), involved in cellular iron homeostasis;[31] (iii) Pro-tRNA (76 nt) as a primer for reverse transcription for murine leukemia virus; [32] and (iv) HIV-1 core encapsidation signal (155 nt) involved in genomic packaging.[33]

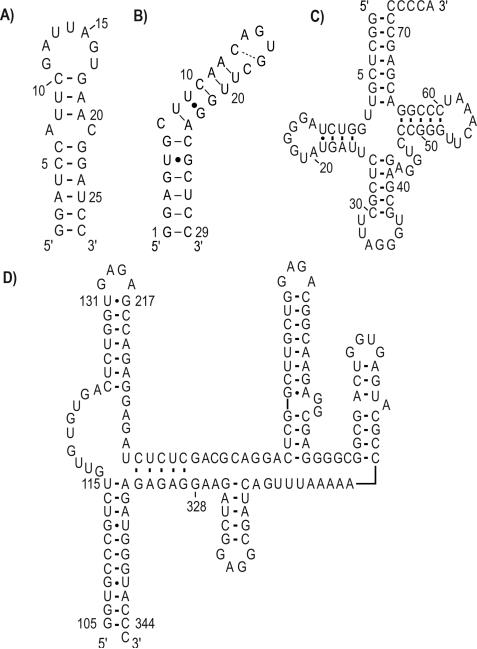

Scheme 2.

Secondary structures for (a) ESS3 RNA (27 nt), (b) IRE RNA (29 nt), (c) Mouse Pro-tRNA (76 nt), and (d) HIV-1 core encapsidation signal RNA (155 nt, based on chemical probing of the intact genome by Watts et al.[42] and partially confirmed by NMR). Dash: Watson-Crick base pairing, Dot: Wobble base pairing.

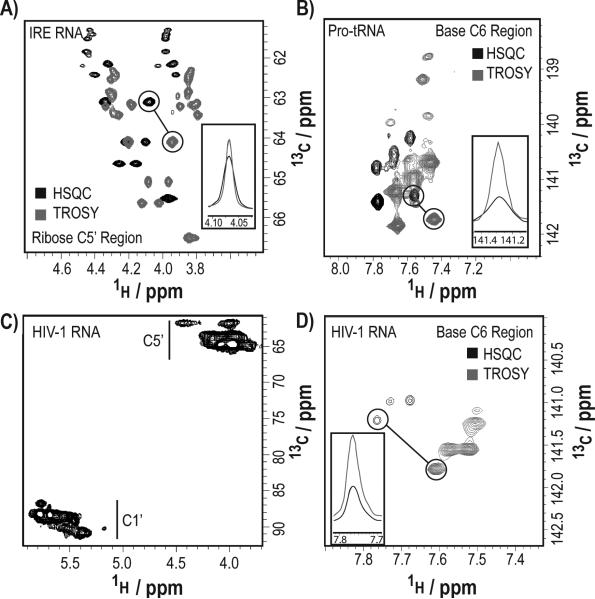

The site-specific labeling of these RNAs significantly reduced spectral crowding, eliminated 13C-13C scalar couplings, increased signal-to-noise ratios, and facilitated direct carbon detection experiments. The average linewidth improvement factor (the ratio of the average 1H linewidth in a regular HSQC to a CH-/CH2-optimized TROSY experiment) was ~1.7 (with a range from 1.1 to 2.5) for C5′-methylene region and 1.9 (with a range of 1.0 to 3.0) for C6-methine (Figure 2a,b,d insets; SI-4).[34] Compared to traditional HSQC experiments, TROSY experiments afforded linewidth and sensitivity improvement (Figure 1).

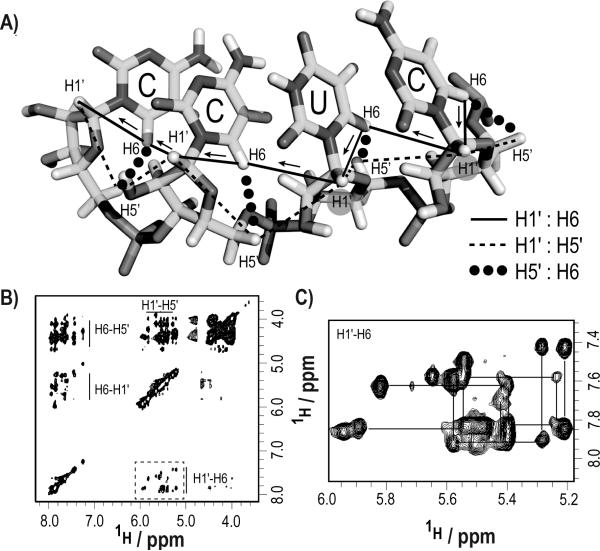

Figure 2.

Through-space NOE resonance assignments for the IRE RNA become straightforward with specifically labeled nucleotides. (a) Intra- and inter-nucleotide sequential 1H walk between H1′, H5′, and H6 along a pyrimidine tract. (b) The spectral crowding in a 3D NOESYHSQC experiment is significantly reduced when using our specifically labeled nucleotides. (c) The NOE sequential walk between H1′i-H5′i/H6i-H1′(i+1) was readily followed for all contiguous pyrimidine tracts. Experimental param eters are detailed in the supplementary information (SI-6).

Figure 1.

Spectral resolution and improved signal-to-noise ratios for site-specifically labeled RNAs. (a) Comparison of HSQC (black) and CH2-TROSY (gray) spectra of the C5′ region of the site-specifically U,C-labeled IRE RNA (29 nt). (b) Comparison of HSQC (black) and CHTROSY (gray) spectra of the C6 region of the site-specifically U-labeled Pro-tRNA (76 nt). (c) HSQC (C1’ and C5’ regions) of the site-specifically U-labeled HIV-1 core encapsidation signal RNA (155 nt). (d) Comparison of HSQC (black) and CH-TROSY (gray) spectra of the C6 region of the site-specifically U-labeled HIV-1 core encapsidation signal RNA (155 nt).

In addition to these spectral quality improvements, our labels open up new avenues for structural analysis of RNA. In a standard duplex RNA helix, H1′ to H5′ and H5′ to H6/H8 nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) contacts are often difficult to analyse because of spectral crowding in the C5′ region due to the limited chemical shift dispersion of H2′, H3′, H4′, and H5′/H5″ resonances (Figure 2).[35] With our new labels, we demonstrate that the interaction between sequential nucleotides “i” and “i+1” involving the pairs H1i′-H5′i/H6i-H1′(i+1) can be readily observed in a 3D NOESY-HSQC experiment (Figure 2b,c). The expected sequential NOEs are clearly visible and permit sequential assignments to be made readily. With this approach we unambiguously traced and assigned all the H1′, H5′, H5″, and H6 proton resonances with contiguous U-C stretches in IRE RNA.

Another set of NMR applications particularly suited for our site-specific labels are direct 13C detection experiments. Advances in NMR probe technology enable acquisition of NMR experiments that bypass the fast-relaxing 1H bottleneck.[36,37] Unlike uniformly 13C/15N labeled samples, applying our selective labels is advantageous for the following reasons: implementation does not require IPAP, S3E, selective pulse implementation, or constant time elements for carbon decoupling in the direct dimension (SI-4). Similarly, the transfer efficiency is not adversely affected by undesired coherence transfers such as C1′↔C2′, C5↔C6, and N1↔C2 without the use of selective pulses (SI-5). For instance, in a selectively U,C-labeled IRE RNA we observed all the expected C1′-N1 and C6-N1 correlations in a 2D carbon-detected CN experiment (Figure 3).

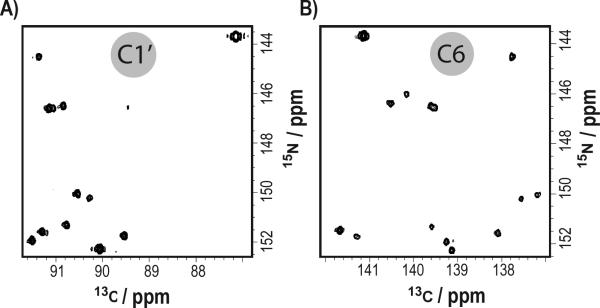

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional direct carbon-detected CN experiments of 0.7mM IRE RNA. (a) C1′-N1 region. (b) C6-N1 region.

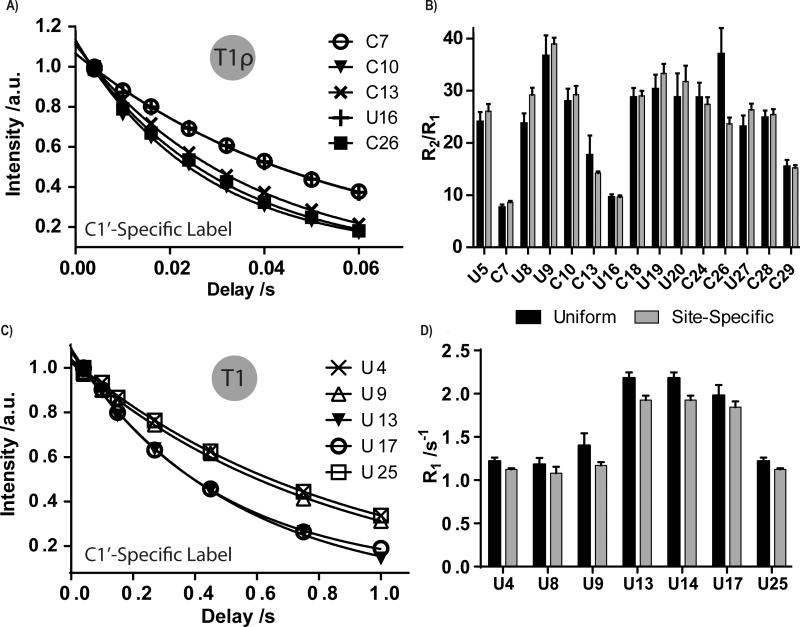

Finally, we also show that RNAs transcribed with our custom nucleotides have better derived NMR dynamics parameters (e.g. T1, T1ρ). For instance, both IRE and ESS3 RNAs showed a near perfect data fit for T1 and T1ρ relaxation experiments, respectively, with our site-specific labels (Figure 4a,c). From our relaxation experiments, best-fit parameters for all RNAs followed a similar pattern, where uniformly labeled RNA consistently had larger standard errors in the measurements.

Figure 4.

Site-specific labeling improves dynamics measurements of the IRE and ESS3 RNAs. (a,c) Curve fits of T1ρ or T1 experiments on five residues of the IRE RNA and ESS3 RNA, respectively. (b,d) Comparison of overall dynamics (R2/R1 ratio or R1 values) of all U and/or C residues of IRE and ESS3 RNAs, respectively, when the molecule was 13C/15N uniformly or site-specifically labeled. In the IRE RNA, U8, C13, and C26 show significant differences in R2/R1 ratios. In ESS3 RNA, U9, U13, and U14 show significant differences in R1 decay rates. Other residues remain unaffected. Errors bars are shown as standard deviation from three independent experiments.

Next, we compared the ns-ps dynamics of both C1′-H1′ and C6-H6 bond vectors as a ratio of R2/R1 decay rate constants. Both IRE and ESS3 RNAs showed a few residues with different decay rate values between uniformly and selectively labeled RNA (Figure 4b,d). Our results underscore the importance of using site-specifically labeled nucleotides to study the structure and dynamics of RNA, especially for RNAs >25 nt. Experimental parameters are detailed in the supplementary information (SI-6).

In conclusion, using a chemical enzymatic method, we have designed an efficient and flexible method for site-specific labeling of gram quantities of pyrimidine nucleotides with up to 90 % yield (based on input uracil). These labeled ribonucleotides enable facile measurement of a range of NMR dynamics (T1, T1ρ) and structural parameters in RNA. In addition, our labels afford NMR spectra with improved linewidths and signal-to-noise ratios for RNAs ranging in size from 27- to 155-nt. Finally, the use of these labels would (i) enable accurate measurement of residual dipolar couplings,[38] (ii) improve the acquisition of RNA heteronuclear chemical shifts to facilitate rapid identification of noncanonical RNA structures within RNA-ligand/protein interaction interfaces,[39] (iii) be useful for solid-state NMR of RNA,[40,41] and (iv) be easily expanded to deuterate C5, C6 or both positions.

Experimental Section

Buffers and reagents

All buffers were prepared with chemicals bought from Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher Scientific. 1′,5′-13C2-D-ribose was purchased from Omicron Biochemicals.

Protein expression and purification

Ribokinase (E.C. 2.7.1.15), Phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase (E.C. 2.7.6.1), Uridine phosphoribosyl transferase (E.C. 2.4.2.9), and CTP synthethase (E.C. 6.3.4.2) were all expressed, purified and assayed for activity as previously described.[28]

UTP synthesis

The site-specifically labeled 1′,5′,6-13C3-1,3-15N2-Uridine triphosphate was synthesized by phosphorylation of uridine monophosphate (UMP); UMP was synthesized from uracil, ribose, and dATP with an overall yield of ~ 90 % with respect to input uracil (Supplementary information).

CTP synthesis

The site-specifically labeled 1′,5′,6-13C3-1,3-15N2-Cytidine triphosphate was enzymatically synthesized in vitro in a single-step reaction as previously described.[13] Our typical yield was 95 % (Supplementary information).

RNA synthesis and purification

All four RNAs (ESS3, IRE, Pro-tRNA, and HIV-1) were synthesized in vitro following standard published protocols. RNAs were then purified by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by electroelution. Finally, RNAs were dialyzed into their buffer of choice (Supplementary information).

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

NMR experiments were carried out on 0.2 to 1 mM RNA samples. Various 1D and 2D proton detected and direct carbon-detect CN experiments were collected at 25 °C on either a 600 and/or 800 MHz Bruker Avance III spectrometer equipped with a HCN triple resonance cryoprobe. All NMR data were processed using TopSpin 3.2, NMRpipe/NMRDraw, and NMRviewJ (Supplementary information, Tables S1 and S2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Institute for General Medical Sciences (P50 GM103297 to BST, MFS, TKD, and VMD), the National Science Foundation (DBI1040158 to TKD), and the Austrian Sciences Fund (I844 to CK).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available

References

- 1.Steitz TA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:242–253. doi: 10.1038/nrm2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breaker RR. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:771–773. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serganov A, Nudler E. Cell. 2013;152:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattick JS. J. Exp. Biol. 2007;210:1526–1547. doi: 10.1242/jeb.005017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu K, Heng X, Garyu L, Monti S, Garcia EL, Kharytonchyk S, Dorjsuren B, Kulandaivel G, Jones S, Hirem ath A, et al. Science. 2011;334:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.1210460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott LG, Tolbert TJ, Williamson JR. Methods Enzymol. 2000;317:18–38. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)17004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikonowicz EP, Sirr A, Legault P, Jucker FM, Baer LM, Pardi A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4507–4513. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.17.4507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, Wüthrich K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dayie KT. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008;9:1214–1240. doi: 10.3390/ijms9071214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wunderlich CH, Spitzer R, Santner T, Fauster K, Tollinger M, Kreutz C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:7558–7569. doi: 10.1021/ja302148g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milecki J. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2002;45:307–337. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quant S, Wechselberger RW, Wolter MA, Wörner K-H, Schell P, Engels JW, Griesinger C, Schwalbe H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:6649–6651. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schultheisz HL, Szymczyna BR, Scott LG, Williamson JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:297–304. doi: 10.1021/ja1059685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batey RT, Inada M, Kujawinski E, Puglisi JD, Williamson JR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4515–4523. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.17.4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman DW, Holland JA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3361–3362. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3361-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemaster DM, Kushlan DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;118:9255–9264. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson JE, Julien KR, Hoogstraten CG, Biomol J. NMR. 2006;35:261–274. doi: 10.1007/s10858-006-9041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thakur CS, Sama JN, Jackson ME, Chen B, Dayie TK, Biomol J. NMR. 2010;48:179–192. doi: 10.1007/s10858-010-9454-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thakur CS, Dayie TK, Biomol J. NMR. 2012;52:65–77. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9582-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tolbert TJ, Williamson JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:7929–7940. [Google Scholar]

- 21.SantaLucia J, Shen LX, Cai Z, Lewis H, Tinoco I. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4913–4921. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.23.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park J, van Koeverden P, Singh B, Gupta RS. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3211–3216. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li S, Lu Y, Peng B, Ding J. Biochem. J. 2007;401:39–47. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sin IL, Finch LR, Bacteriol J. 1972;112:439–444. doi: 10.1128/jb.112.1.439-444.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundegaard C, Jensen KF. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3327–3334. doi: 10.1021/bi982279q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinha SC, Smith JL. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:733–739. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(01)00274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lunn FA, MacDonnell JE, Bearne SL. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:2010–2020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arthur PK, Alvarado LJ, Dayie TK. Protein Expr. Purif. 2011;76:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacDonnell JE, Lunn FA, Bearne SL. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1699:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levengood JD, Rollins C, Mishler CHJ, Johnson CA, Miner G, Rajan P, Znosko BM, Tolbert BS. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;415:680–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pantopoulos K, Porwal SK, Tartakoff A, Devireddy L. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5705–5724. doi: 10.1021/bi300752r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harada F, Peters GG, Dahlberg JE. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:10979–10985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heng X, Kharytonchyk S, Garcia EL, Lu K, Divakaruni SS, LaCotti C, Edme K, Telesnitsky A, Summers MF. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;417:224–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miclet E, Williams DC, Jr, Clore GM, Bryce DL, Boisbouvier J, Bax A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:10560–10570. doi: 10.1021/ja047904v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wijmenga SS, van Buuren BNM. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 1998;32:287–387. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bermel W, Felli IC, Kummerle R, Pierattelli R. Concepts Magn. Reson. Part A. 2008;32A:183–200. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bermel W, Bertini I, Felli IC, Pierattelli R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:15339–15345. doi: 10.1021/ja9058525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ying J, Wang J, Grishaev A, Yu P, Wang Y-X, Bax A, Biomol J. NMR. 2011;51:89–103. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9544-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barton S, Heng X, Johnson BA, Summers MF, Biomol J. NMR. 2013;55:33–46. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9683-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.V Cherepanov A, Glaubitz C, Schwalbe H. Angew. Chemie. 2010;49:4747–4750. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marchanka A, Simon B, Carlomagno T. Angew. Chemie. 2013;52:9996–10001. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watts JM, Dang KK, Gorelick RJ, Leonard CW, Bess JW, Swanstrom R, Burch CL, Weeks KM. Nature. 2009;460:711–716. doi: 10.1038/nature08237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.