Abstract

Skin-derived dendritic cells (DCs) play a crucial role in the maintenance of immune homeostasis due to their role in antigen trafficking from the skin to the draining lymph nodes (dLNs). To quantify the spatiotemporal regulation of skin-derived DCs in vivo, we generated knock-in mice expressing the photoconvertible fluorescent protein KikGR. By exposing the skin or dLN of these mice to violet light, we were able to label and track the migration and turnover of endogenous skin-derived DCs. Langerhans cells and CD103+DCs, including Langerin+CD103+dermal DCs (DDCs), remained in the dLN for 4–4.5 days after migration from the skin, while CD103−DDCs persisted for only two days. Application of a skin irritant (chemical stress) induced a transient >10-fold increase in CD103−DDC migration from the skin to the dLN. Tape stripping (mechanical injury) induced a long-lasting four-fold increase in CD103−DDC migration to the dLN and accelerated the trafficking of exogenous protein antigens by these cells. Both stresses increased the turnover of CD103−DDCs within the dLN, causing these cells to die within one day of arrival. Therefore, CD103−DDCs act as sentinels against skin invasion that respond with increased cellular migration and antigen trafficking from the skin to the dLNs.

Dendritic cells (DCs) in peripheral tissues carry self- and exogenous-antigens to the draining lymph nodes (dLNs)1. In the dLN, these antigen-carrying migratory DCs not only present the antigens directly to T cells but also transfer the antigens to LN-resident DCs. LN-resident DCs efficiently present the incoming antigens to T cells, using a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-binding product to prime CD8+ T cells, and an MHC class II-binding product to prime CD4+ T cells2,3. Dendritic cell apoptosis and subsequent phagocytosis of the apoptotic bodies by LN-resident DCs has been proposed as a possible mechanism for inter-DC antigen transfer2,3,4. Inter-DC antigen transfer is thought to be involved in self-tolerance in the steady state2,5, priming cytotoxic CD8+ T cells to viruses6,7, and the amplification of DC vaccination8. Thus, elucidation of the spatiotemporal dynamics of DC migration in vivo, particularly in terms of DC movement from peripheral tissues to the dLN and the turnover rate and lifespan of DCs within the dLN, will guide the development of new strategies for the regulation of DC-driven immune responses and vaccination.

Skin-derived DCs consist of Langerhans cells (LCs) and dermal DCs (DDCs). LCs reside in the epidermis and DDCs in the dermis. DDCs can be further subdivided into classical Langerin−CD103− DDCs (CD103−DDCs) and recently identified Langerin+CD103+ DDCs9,10. A recent study showed that LCs activate skin-resident regulatory T cells and maintain skin homeostasis11. Langerin+CD103+ DDCs play a role in antigen cross-presentation12,13,14, whereas CD103−DDCs are responsible for the transport of invading pathogens to the dLN15,16,17. For example, CD103−DDCs have been reported to transfer antigen to CD8α+ LN-resident DCs after herpes simplex virus infection of the skin3.

Accumulating evidence suggests that the skin may be one of the main pathways leading to the establishment of systemic immunity to exogenous protein antigens, as occurs in food allergies and asthma18. However, the mechanisms by which exogenous protein antigens cause sensitization via the skin and the role of DCs in the trafficking of these antigens remain poorly understood. Skin-derived DCs remain in an immature state while in the skin. After spontaneous maturation, or after being activated by various stimuli, they migrate to dLNs19, where they are believed to die20,21,22. The in vivo cellular dynamics of skin-derived DCs in the steady state have been analyzed extensively using BrdU experiments23,24,25, parabiosis experiments25,26,27, and experiments that measured repopulation time following depletion13. Although the steady state turnover rate of DC subsets in the skin has been determined previously28, the turnover rate of skin-derived DC subsets in the dLNs remains unclear. Following epicutaneous application of a fluorescent dye and a chemical stressor (skin irritant painting), large numbers of fluorescently labeled skin-derived DCs are detected in the dLN3,17,29. However, because the number of labeled cells detected in the dLN in these experiments represents the sum of cell influx and cell efflux or death, skin irritant painting experiments alone do not allow quantitation of the extent to which skin-derived DCs accumulate in the dLN. Thus, by existing methods, it has been difficult to quantify accurately the movement and lifespan of skin-derived DC subsets.

To overcome the limitations of existing approaches to DC tracking and quantification, we recently established a system for monitoring the movement of endogenous skin-derived DCs and other immune cells in vivo by using Kaede-transgenic mice, which express the green-to-red photoconvertible protein Kaede30,31,32. In the present study, we describe the establishment of KikGR knock-in mice, which allow cell type-specific expression of the photoconvertible fluorescent protein KikGR, a protein originally engineered from stony coral33. Like Kaede, KikGR fluorescence also changes irreversibly from green to red upon exposure to violet light, however KikGR has considerably greater photoconversion efficiency. We used KikGR knock-in mice to label DCs within the skin and dLN red, thus allowing us to quantify endogenous skin-derived DC dynamics in the steady state and the spatiotemporal changes that occur amongst skin-derived DCs in the dLN following chemical stress and mechanical injury to the skin.

Results

Tracking of DC movement from the skin to the dLN using the photoconvertible protein KikGR

Quantification of endogenous DC migration from the skin to the dLN in the steady state is fundamental to understanding the dynamics of skin-derived DCs in vivo. Experiments that paint fluorescent dye onto the skin (even when a skin irritant is not specifically included) do not adequately represent the steady state because the organic solvents and protein modifications involved are likely to affect DC dynamics. To track skin DCs without using skin irritant painting, we generated ROSA26-loxP-stop-loxP-KikGR knock-in mice, from which cell type-specific KikGR expression can be achieved through mating with an appropriate Cre-expressing mouse strain34. In the present study, we cross-mated ROSA26-loxP-stop-loxP-KikGR mice with CAG-Cre mice in order to delete the loxP-stop-loxP site and achieve KikGR expression in all cells of the mice (hereafter, “KikGR mice”) due to the ubiquitous expression of the CAG promoter (Supplementary Fig. S1).

To track DC migration from the skin to the dLN, the abdominal hair of KikGR mice was clipped, and the skin was exposed to violet light (436 nm) to induce photoconversion of the KikGR protein from green (KikGR-green) to red (KikGR-red)(Fig. 1A). Unlike shorter wavelenths, exposure to violet light in this manner does not cause inflammation or other immunomodulatory effects30,32,35. Although 100% of the cells in violet light-exposed skin were KikGR-red immediately after photoconversion, cells in non-photoconverted skin and in the axillary dLNs remained KikGR-green (Fig. 1B).

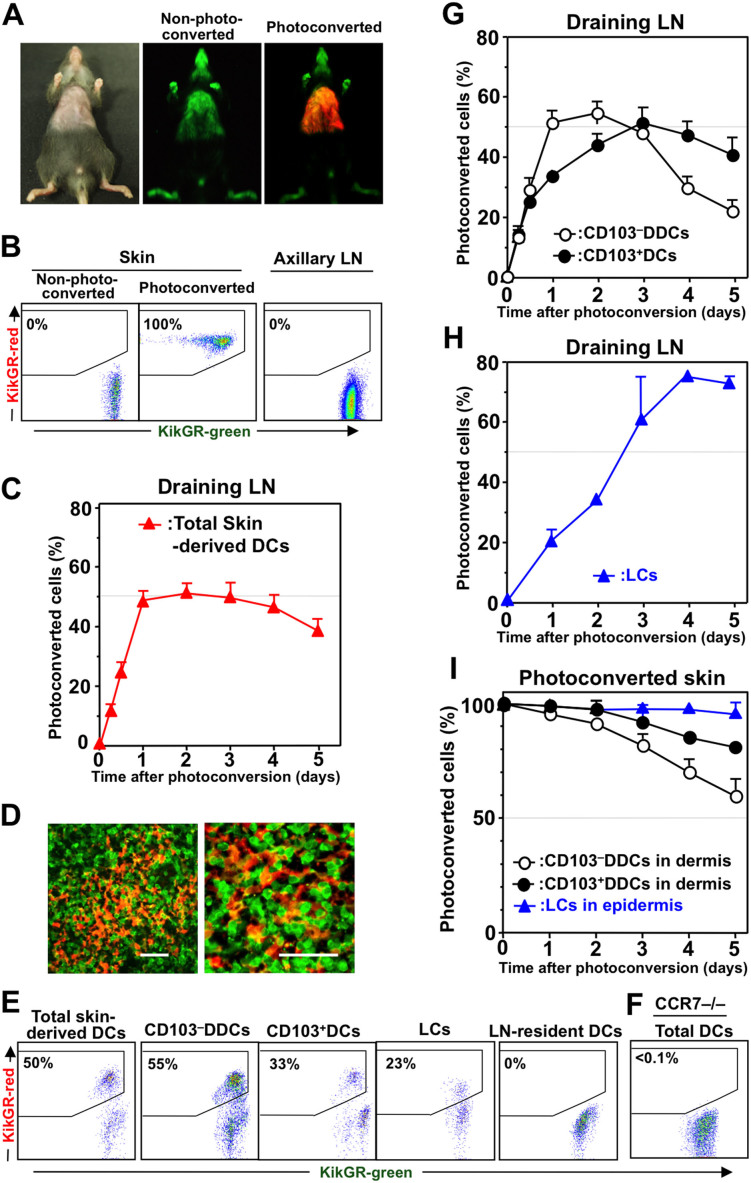

Figure 1. Each skin-derived DC subset displays distinct migration kinetics in its migration from the skin to the dLN.

(A) The clipped abdominal skin of KikGR mice was photoconverted by exposure to violet light before examination under a stereoscopic fluorescence microscope. Unclipped areas of skin remained black because the photoconversion light could not reach them. (B) The skin and axillary dLNs were resected immediately after skin photoconversion, or from non-photoconverted mice, and the cells from these tissues isolated for analysis by flow cytometry. (C) Following skin photoconversion, cells from the dLNs were isolated and stained for analysis of skin-derived DCs by flow cytometry (see Supplementary Fig. S2A for gating strategy). Data represent the proportion of skin-derived DCs labeled KikGR-red. (D) Sections of dLNs collected from KikGR-BM→WT mice 24 h after skin photoconversion were observed under a confocal microscope. Scale bars, 40 μm. (E) Flow cytometry plots showing KikGR-green and KikGR-red cells within each DC subpopulation in the dLN 24 h after skin photoconversion. (F) Flow cytometry plot showing KikGR-green and KikGR-red DCs (CD11c+ cells) within the dLN of CCR7–/– KikGR mice 24 h after skin photoconversion. (G) Total skin-derived DCs from the dLN of KikGR mice after skin photoconversion (as in panel C) were further gated into CD103–DDCs and CD103+DCs (see Supplementary Fig. S3 for gating strategy). (H) Following skin photoconversion, cells from the dLN of WT-BM→KikGR chimeric mice were isolated and stained for analysis of LCs by flow cytometry (see Supplementary Fig. S4 for gating strategy). Data in G and H represent the proportion of each subpopulation labeled KikGR-red. (I) After skin photoconversion, single-cell suspensions from the epidermis and dermis were analyzed by flow cytometry as described in Supplementary Fig. S2B. Percentages on flow cytometry dot plots (B, E and F) indicate the proportion of KikGR-red cells within each subpopulation. At least four samples from each time point were analyzed. Data represent mean ± SE (C, G, H, and I) and are representative of three independent experiments.

Skin-derived DCs were identified as CD11c+ MHC class IIhigh cells10 (Supplementary Fig. S2A). On average, 1.2 ± 0.4 × 104 (mean ± SD) skin-derived DCs were present in each dLN. KikGR-red skin-derived DCs were detected in the dLN as early as 6 h after skin photoconversion (Fig. 1C). The proportion of these cells in the dLN reached a plateau on day one, maintained this level until day three, then decreased gradually. In addition, KikGR-red cells with DC morphology were observed in the dLN one day after photoconversion (Fig. 1D).

Representative flow cytometry plots showing the proportions of KikGR-red cells within the skin-derived DC and LN-resident DC populations in the dLN one day after photoconversion are presented in Fig. 1E. LN-resident DCs in the dLN were gated as CD11chigh MHC class IIint cells10 (Supplementary Fig. S2A). It should be noted that no KikGR-red cells were detected within the LN-resident DC population in the dLNs of KikGR mice after skin photoconversion (Fig. 1E), or within any DC populations in the dLNs of CCR7–/– KikGR mice after skin photoconversion (Fig. 1F). These results demonstrate that CCR7 signaling is crucial for DC migration from the skin to the dLNs, as has been reported previously19,36,37.

Each skin-derived DC subset displays distinct migration kinetics in its migration from the skin to the dLN

The skin-derived DCs found in the dLN could be further divided into subsets based on their expression of CD103 and CD326 (Supplementary Fig. S3). Langerin−CD103−DDCs (hereafter “CD103−DDCs”) were identified as a CD103−CD326− population that represented 68% ± 7.5% SD of total skin-derived DCs in the dLN. CD103+CD326int DCs (hereafter “CD103+DCs”) represented 12% ± 4.2% SD of total skin-derived DCs, and approximately 50% of these cells consisted of Langerin+CD103+DCs when visualized using Langerin-GFP mice (Supplementary Fig. S3).

In the dLN, the proportion of KikGR-red CD103−DDCs reached a plateau of 55% within one day of photoconversion, then began to decline gradually from day three (Fig. 1G). This result suggests that self-antigens present on CD103−DDCs are delivered rapidly from the skin to the dLN. On the other hand, KikGR-red CD103+DCs reached a plateau on day three after photoconversion. LCs were identified as a radioresistant CD103−CD326+ population25 (Supplementary Fig. S4). The proportion of KikGR-red LCs in the dLNs increased more slowly than other skin-derived DC subsets, but reached a plateau of approximately 75% on day four after photoconversion (Fig. 1H; experiments conducted in WT-BM→ KikGR chimeras).

When DCs in the skin of the ears were labeled by photoconversion, KikGR-red cells were detected in auricular dLNs. Although the proportions of photoconverted cells migrating to the dLNs were lower than those observed following abdominal skin photoconversion, the kinetics of KikGR-red cell migration for each DC subset were similar to the patterns observed for migration from the abdominal skin (Supplementary Fig. S5). These results suggest that the peak and plateau levels of KikGR-red skin-derived DCs in the dLN were related to the total skin area that was exposed to photoconversion.

We next examined the proportion of KikGR-red cells within the populations of CD103−DDCs, CD103+DDCs and epidermal LCs in the skin itself (Fig. 1I; cells identified as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2B). In the photoconverted skin, the proportion of KikGR-red CD103−DDCs decreased faster than CD103+DCs (Fig. 1I). As the number of KikGR-red cells in the skin decreases, more KikGR-green (non-photoconverted) cells would be expected to start flowing to the dLNs. In turn, an increased number of KikGR-green CD103−DDCs migrating from the skin to the dLN and more rapid replacement of KikGR-red CD103−DDCs in the dLN would explain why the accumulation of KikGR-red CD103−DDCs peaked earliest of all skin-derived DC subsets in the dLN following photoconversion. The observation that the proportion of KikGR-red CD103−DDCs in the dLN began to decrease three days after photoconversion of the skin (Fig. 1G and Supplementary Fig. S5) suggests that it took only three days for KikGR-green (non-photoconverted) monocytes to migrate into the photoconverted skin, differentiate into KikGR-green CD103−DDCs, and migrate to the dLN.

On the other hand, LCs in the epidermis remained KikGR-red for more than five days (Fig. 1I). This observation is consistent with the notion that LCs in the dermis are not replaced by blood-supplied precursors in the steady state25. As a result, only KikGR-red LCs (very few KikGR-green LCs) migrated to dLN, explaining why KikGR-red LCs continue to accumulate in the dLN, reaching a plateau four days after photoconversion (Fig. 1H). Furthermore, the plateau level for KikGR-red LCs in the dLN (75%) was similar to the proportion of the skin draining to the axillary dLNs that was covered by the abdominal photoconversion area (76%, the maximum possible proportion of KikGR-red skin-derived DCs in the dLN), as determined by sequential repeat photoconversion of the skin (Supplementary Fig. S6). Thus, the kinetics of the accumulation of KikGR-red skin-derived DC subsets in the dLN corresponded with their rates of egress from the photoconverted skin.

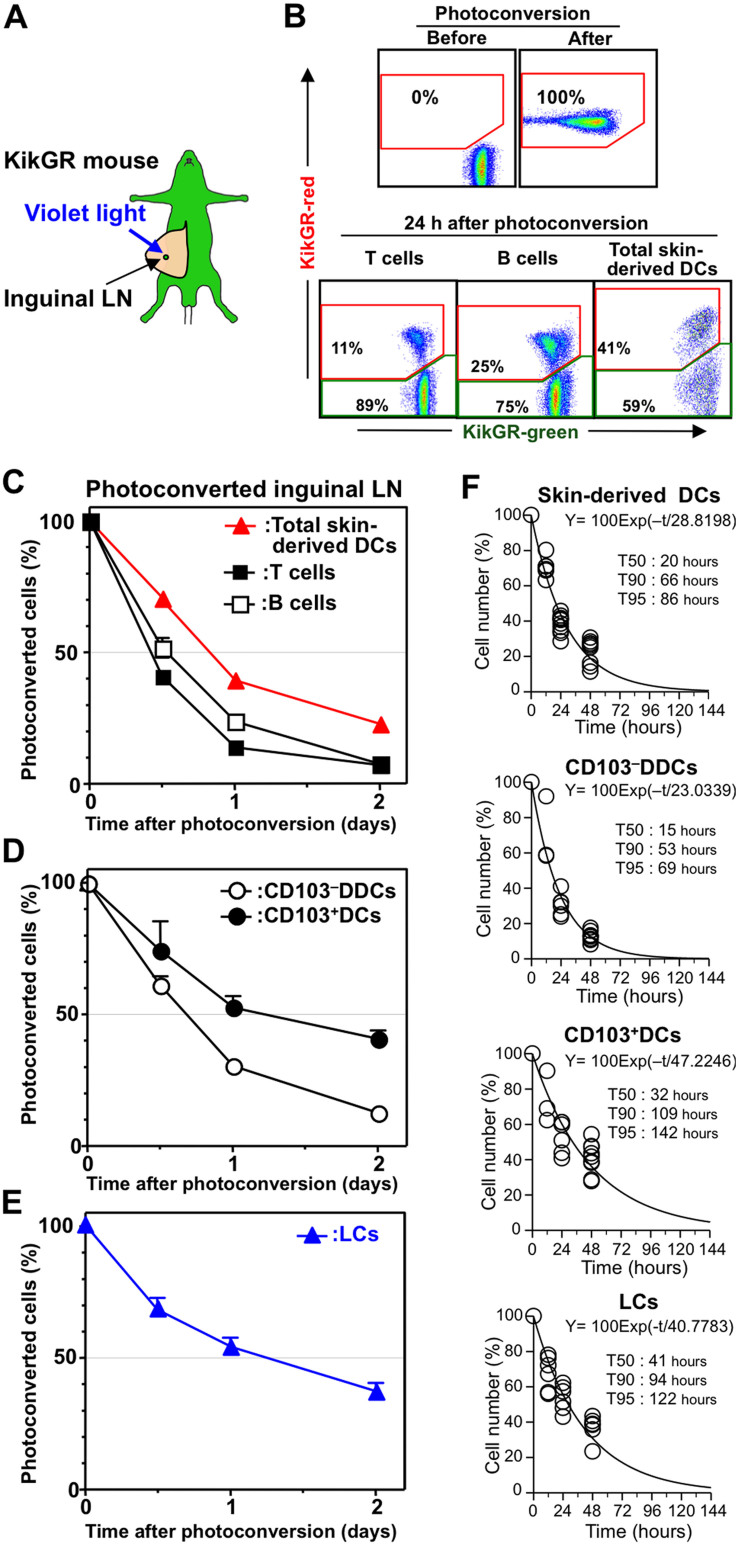

Determination of the steady-state replacement rate for skin-derived DCs in the LN

Previous studies have used BrdU administration to show that the average lifespan of DDCs in the LN is approximately 2–3 days24, and that the turnover of Langerin−DDCs (CD103−DDCs) in the dLNs is faster than that of Langerin+DDCs and LCs25,38. However, the lifespan of skin-derived DC subsets in the dLN is difficult to measure because of the initial lag in the BrdU labeling of skin-derived DCs in the dLN, and the low BrdU uptake by LCs23,24,25. We have reported previously that replacement of T and B cells in the LN can be monitored using Kaede transgenic mice30,31. In the present study, we used KikGR mice to determine the lifespan of skin-derived DCs in the dLN, based on their replacement rate. Immediately after photoconversion of the inguinal LN in KikGR mice (Fig. 2A), 100% of cells in the photoconverted LN appeared KikGR-red (Fig. 2B). Representative flow cytometry plots showing KikGR-red cells in the T cell, B cell and skin-derived DC populations one day after photoconversion are presented in Fig. 2B. Time course analysis revealed that the replacement of total skin-derived DCs in the dLN was slower than the replacement of T and B cells (Fig. 2C). However, 62% and 80% of KikGR-red skin-derived DCs had been replaced within one and two days of photoconversion, respectively. Furthermore, 70% and 90% of KikGR-red CD103−DDCs had been replaced within one and two days of photoconversion, respectively (Fig. 2D). On the other hand, CD103+DCs and LCs were replaced more slowly (Fig. 2 D and E). Based on the data shown in Fig. 2 C–E, we used exponential line-fitting to estimate the replenishment halflife (T50, the time for 50% of cells to be replaced) and the lifespan (T90, the time for 90% of cells to be replaced) for each DC subset in the LN (Fig. 2F and Supplementary Fig. S7). The estimated lifespan (T90) for skin-derived DCs in the LN was approximately 66 h. Among these cells, CD103−DDCs had the shortest lifespan (53 h) compared to CD103+DCs (109 h) and LCs (94 h). Thus, while DC lifespan varied between subsets, these data suggest that skin-derived DCs disappear from the dLN within 2 to 4.5 days of their arrival.

Figure 2. Turnover of skin-derived DCs within the LN.

(A) Photoconversion of the inguinal LN in KikGR mice. (B, upper plots) Cells from a non-photoconverted LN or isolated from the LN immediately after photoconversion were analyzed by flow cytometry. (B, lower plots) Cells isolated from the LN 24 h after photoconversion were stained with fluorochrome-labeled anti-CD19, CD11c, MHC II, and CD3 mAbs to enable analysis of the proportions of KikGR-green and KikGR-red cells within populations of T cells (CD3+), B cells (CD19+), and skin-derived DCs (CD11c+ MHC IIhigh). (C and D) Cells isolated from the photoconverted inguinal LN were analyzed by flow cytometry (staining for C was the same as panel B; staining for D is described in Supplementary Fig. S3). Data represent the proportion of each subpopulation labeled KikGR-red. (E) Cells from the photoconverted LN of WT-BM→KikGR chimeric mice were isolated and stained for analysis of LCs by flow cytometry (see Supplementary Fig. S4 for gating strategy). Data represent the proportion of each subpopulation labeled KikGR-red. At least four samples from each time point were analyzed. Data represent mean ± SE (C, D, and E) and are representative of three independent experiments. (F) Exponential line-fitting based on the decrease in the number of KikGR-red skin-derived DCs in the inguinal LN following photoconversion (C–E) was used to calculate T50, T90 and T95 (the time for 50%, 90% and 95% of cells to be replaced, respectively). Individual data points (circles), fitting lines and the associated exponential equation are shown. Illustration created by M.T. using Adobe Photoshop software.

The fate of skin-derived DCs in the LN

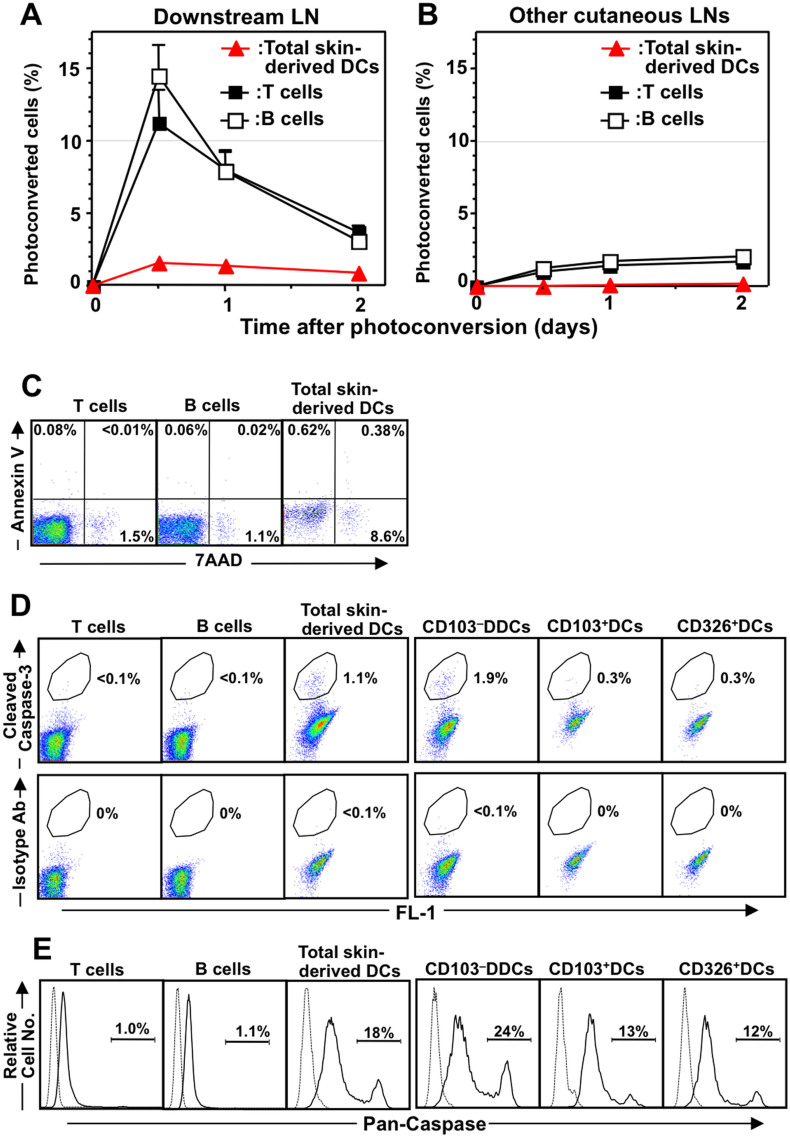

The questions of whether skin-derived DCs exit the dLN after they have arrived from the skin and whether skin-derived DCs are involved in antigen presentation beyond the dLN remain controversial39. We therefore used the KikGR photoconversion method to examine whether skin-derived DCs from a photoconverted inguinal LN migrate to a downstream ipsilateral axillary LN directly through connecting lymphatic vessels, and from there to other LNs via the lymphatic system and the general circulation. Photoconversion of the inguinal LN resulted in the rapid appearance of a sharp peak in the proportion of KikGR-red T and B cells in the downstream LN, and subsequent accumulation in other LNs in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 3 A and B), which is consistent with the results of previous studies30,31. However, KikGR-red skin-derived DCs from the photoconverted inguinal LN made up only 1% of cells in the downstream LN, and were not detected in other LNs at any time following photoconversion (Fig. 3 A and B). These results suggest that it is difficult for skin-derived DCs to exit the LN, and that the majority of skin-derived DCs do not recirculate from the dLN.

Figure 3. The fate of skin-derived DCs in the LN.

(A and B) After photoconversion of the inguinal LN in KikGR mice, cells were isolated from the ipsilateral axillary LN (“Downstream LN”; A) and cervical LN (“Other cutaneous LNs”; B) for analysis by flow cytometry (staining as in Fig. 2B). Data (mean ± SE) represent the proportion of each subpopulation labeled KikGR-red. At least four samples from each time point were analyzed. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Cells from cutaneous LNs were stained with fluorochrome-labeled anti-CD3, anti-CD19, anti-MHC II, anti-CD11c, Annexin V, and 7-amino actinomycin-D (7-AAD) before analysis by flow cytometry. Dot plots show Annexin V and 7-AAD expression in T cells (CD3+), B cells (CD19+) and skin-derived DCs (CD11c+ MHC IIhigh). (D) Cells from cutaneous LNs were stained with fluorochrome-labeled anti-CD19, CD11c, MHC II, and CD3 mAbs or as described in Supplementary Fig. S3, then further stained with anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody or isotype control Ab, followed by fluorochrome-conjugated anti-rabbit Ab. Flow cytometry dot plots show the proportion of cleaved caspase-3 positive cells amongst T cells (CD3+), B cells (CD19+), skin-derived DCs (CD11c+ MHC IIhigh), and skin-derived DC subsets (CD103–DDCs, CD103+DCs, and CD326+DCs; see Supplementary Fig. S3 for gating strategy). (E) Cells from cutaneous LNs were cultured with FLICA then stained as in panel D. Flow cytometry histograms show pan-caspase activity in T cells (CD3+), B cells (CD19+), skin-derived DCs (CD11c+ MHC IIhigh), and skin-derived DC subsets (CD103–DDCs, CD103+DCs, and CD326+DCs). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

We therefore investigated whether apoptotic skin-derived DCs were present in the dLN. Because it was difficult to detect TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells in histological sections of the dLN (data not shown), we attempted to detect apoptotic DCs by other methods. Compared with T cells and B cells, a considerably higher proportion of skin-derived DCs were positive for 7-amino-actinomycin D (a marker of non-viable cells) and cleaved caspase-3 (a marker of apoptosis) (Fig. 3 C and D). Furthermore, 18% of skin-derived DCs were positive for caspase activity, while virtually no T and B cells in the LN displayed caspase activity (Fig. 3E). Interestingly, a greater proportion of CD103−DDCs displayed caspase activity compared to other DC subsets (Fig. 3 D and E), which is consistent with the shorter lifespan for CD103−DDCs that was calculated based on KikGR photoconversion experiments. Taken together, the lack of recirculation of skin-derived DCs to downstream LNs and the greater tendency of these cells to undergo apoptosis suggest that cell death within the dLN is the most likely fate for the majority of skin-derived DCs.

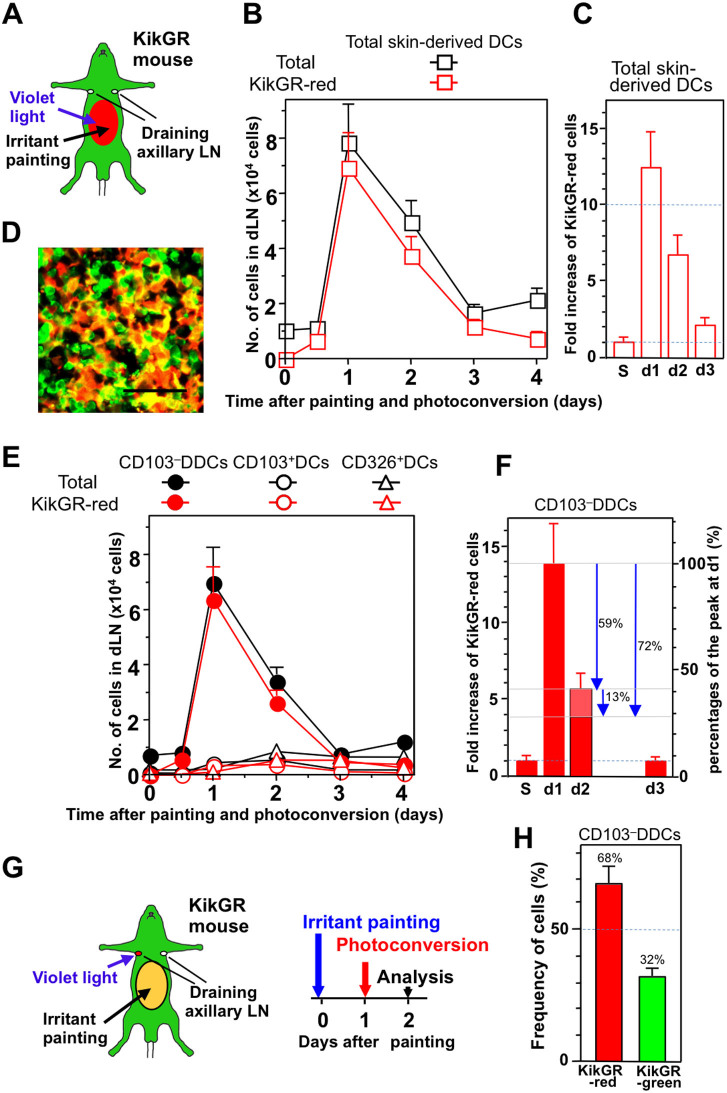

Skin irritant painting promotes the migration and turnover of CD103−DDCs

Previous studies have reported that the appearance of labeled skin-derived Langerin−DDCs (including CD103−DDCs) in the dLN precedes the appearance of Langerin+ DCs following the application of a fluorescent dye and a chemical stressor to the skin3,17,24. We therefore attempted to quantify changes in skin-derived DC dynamics after inducing skin inflammation in KikGR mice. The abdominal skin of KikGR mice was photoconverted, painted with a skin irritant, and the appearance of KikGR-red cells in an axillary dLN was analyzed (Fig. 4A). One day after photoconversion and painting, the number of KikGR-red skin-derived DCs in the dLN had increased more than 12-fold (Fig. 4B and “d1” in Fig. 4C) compared to the number of KikGR-red cells present in the steady state (“S” in Fig. 4C), and large numbers of KikGR-red cells with DC-like morphology were observed in the dLN (Fig. 4D). The increase in skin-derived DCs in the dLN following skin irritant painting was largely the result of an increase in KikGR-red CD103−DDCs (Fig. 4 E and F). Intriguingly, however, in contrast to the findings of previous skin irritant painting studies3,17,24, only very small increases in the number of cells from other subsets (including Langerin+ DCs) were detected in the dLN during the later phases after painting (on days three and four) (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4. Skin irritant painting promotes the migration and turnover of CD103–DDCs.

(A–F) The clipped abdominal skin of KikGR mice was photoconverted by exposure to violet light, then the same region was painted with a skin irritant (acetone:dibutylphthalate mixture) (A). At the time points indicated, cells isolated from the axillary dLNs were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs for analysis by flow cytometry. (B) Graph shows total cell number and KikGR-red cell number of skin-derived DCs (see Supplementary Fig. S2A for gating strategy). (C) Fold increases relative to the steady state (S) of KikGR-red skin-derived DCs in the dLN after skin photoconversion. (D) Sections of axillary LNs from KikGR-BM→WT chimeric mice 24 h after skin photoconversion and irritant painting were examined under a confocal microscope. Scale bars, 40 μm. (E) Graph shows total cell number and KikGR-red cell number of CD103–DDCs, CD103+DCs, and CD326+DCs (see Supplementary Fig. S3 for gating strategy). (F) Fold increases relative to the steady state (S) of KikGR-red CD103–DDCs in the dLN after skin photoconversion. Percentage decreases relative to the peak KikGR-red CD103–DDC number on day 1 are indicated by blue arrows. At least four samples were analyzed for each time point. Cell numbers within each population were calculated by multiplying total cell number by percentages as determined by flow cytometry, and are presented as mean ± SE. (G and H) The clipped abdominal skin of KikGR mice was painted with a skin irritant on day zero, before photoconversion of the axillary dLNs on day one and flow cytometry analysis of the dLNs on day two (G). (H) Graphs shows the proportions (mean ± SE; n = 3) of CD103–DDCs in the dLN that were KikGR-red and KikGR-green. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Illustration created by M.T. using Adobe Photoshop software.

The number of KikGR-red CD103−DDCs in the dLN had increased 14-fold one day after skin irritant painting (Fig. 4F), but then decreased by 59% of this peak on day two (Fig. 4F, indicated by arrow). Because the number KikGR-red DCs detected on day two in the dLN represents the sum of the influx and efflux or death of KikGR-red DCs, we carried out LN photoconversion experiments to determine the true extent of KikGR-red CD103−DDC loss that occurs between day one and day two. After photoconversion of the axillary dLNs on day one, the cells therein were analyzed on day two (Fig. 4G). Thirty-two percent of CD103−DDCs in the dLN on day two were KikGR-green cells, meaning that 32% of CD103−DDCs had newly entered the dLN between day one and day two (Fig. 4H). Based on this data, we estimate that this new influx is equivalent to 13% of the peak KikGR-red cell number detected in the dLN (since 100%–59% = 41% represents the ‘increase' in KikGR-red cells above steady state that is present on day two, and 32% of these cells are new arrivals between days one and two, thus new influx is 32% × 41% = 13%). Thus, in total, 72% (59% + 13%) of KikGR-red cells were lost from the dLN during the 24 h interval between day one and day two (Fig. 4F, indicated by arrows).

Taken together, these results indicate that epicutaneous application of a skin irritant triggers a >10-fold transient increase in the migration of CD103−DDCs from the skin to the dLNs, but also results in the rapid loss of 72% of CD103−DDCs from the dLN over a 24 h period (Supplementary Fig. S7).

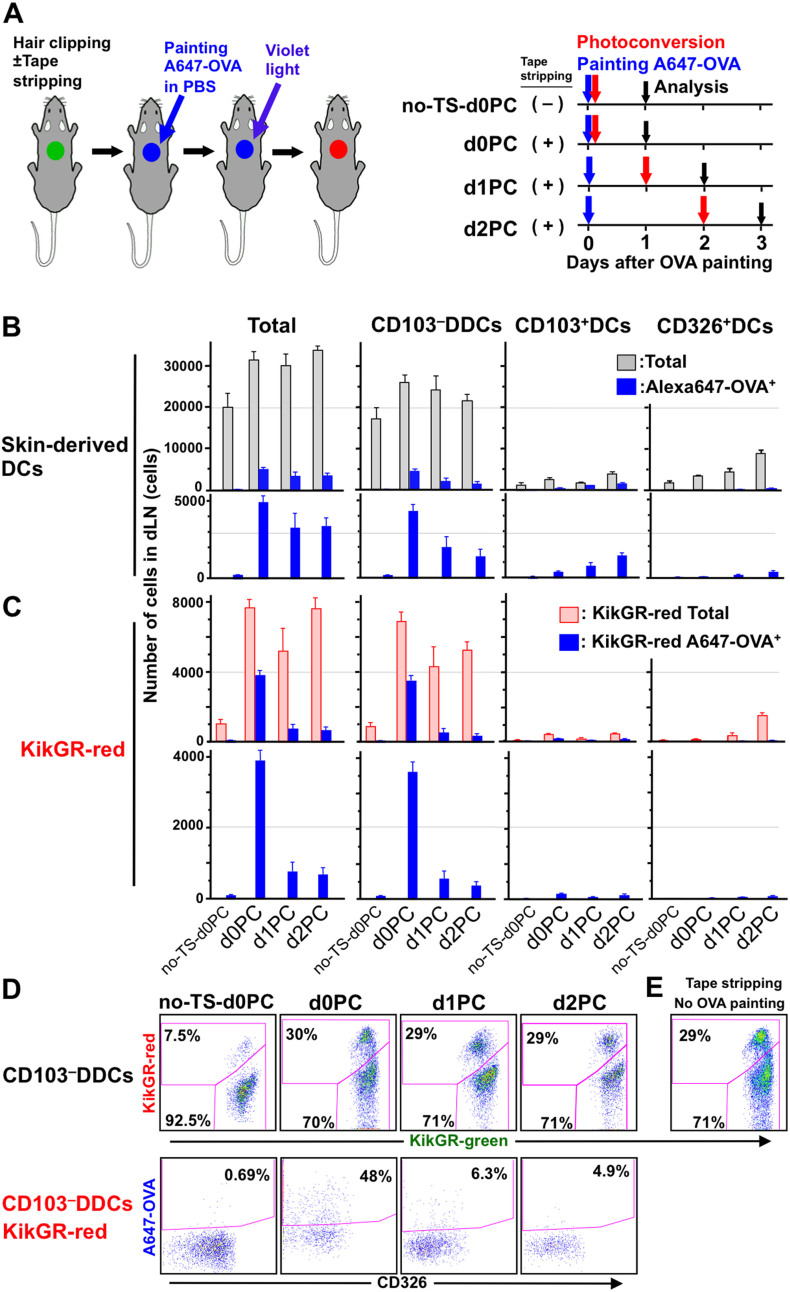

Tape stripping promotes exogenous protein trafficking, migration to the dLN, and the rapid loss of CD103−DDCs from the dLN

Mechanical injury to the skin, such as tape stripping, which removes the stratum corneum, disrupts the permeability of the epithelial barrier and induces the maturation and emigration of LCs from the epidermis40. We therefore examined changes in the migration patterns of skin-derived DCs and exogenous protein trafficking following tape stripping. As depicted in Fig. 5A, the dorsal skin of KikGR mice was subjected to tape stripping and painting with Alexa647-obalbumin (OVA) in PBS, then photoconverted either immediately (d0PC group), after one day (d1PC group), or after two days (d2PC group), with analysis of the dLN one day after photoconversion in each case. Following tape stripping and protein painting, numbers of skin-derived DCs (gray column) and Alexa647+ skin-derived DCs (blue column) in the dLN were elevated on days 1–3 (d0PC, d1PC, and d2PC groups) compared to the no tape stripping control group (no-TS-d0PC group) (Fig. 5B). The increase in skin-derived DCs in the dLN was made up primarily of KikGR-red CD103−DDCs (Fig. 5C). In the d0PC group, almost half of KikGR-red cells consisted of Alexa647+ (i.e. exogenous protein-carrying) cells (Fig. 5 C and D), and the majority (92%) of KikGR-red Alexa647+ cells were CD103−DDCs (Fig. 5C). These results clearly indicate that exogenous protein is carried from the skin to the dLN by CD103−DDCs. In addition, the number of Alexa647+CD103−DDCs was 6- to 10-fold higher in the d0PC group than at the other time points, suggesting that the trafficking of exogenous protein to the dLN is greatest on the first day after tape stripping (Fig. 5 C and D).

Figure 5. Tape stripping promotes exogenous protein trafficking, migration to the dLN, and the rapid loss of CD103–DDCs from the dLN.

(A) The dorsal skin of KikGR mice was clipped, subjected to tape stripping (some mice only), painted with Alexa647-conjugated OVA (A647-OVA) and photoconverted according to the timeline shown for each treatment group. (B–D) At the time points indicated, cells isolated from the brachial dLNs were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs for analysis of total skin-derived DCs, CD103–DDCs, CD103+DCs, and CD326+DCs by flow cytometry (see Supplementary Fig. S2A and Supplementary Fig. S3 for gating strategy). Cell numbers within each population were calculated by multiplying total cell numbers by percentages as determined by flow cytometry, and are presented as mean ± SE (B and C). Flow cytometry dot plots showing KikGR-green vs. KikGR-red cells within the CD103–DDC population (upper plots) and CD326 vs. A647-OVA within the KikGR-red CD103–DDC population (lower plots) (D). At least four samples were analyzed for each time point. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (E) Flow cytometry dot plot showing KikGR-green vs. KikGR-red cells within the CD103–DDC population 24 h after tape stripping without OVA painting. Percentages on flow cytometry dot plots indicate the proportion of KikGR-red or A647-OVA+ cells within each subpopulation. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Illustration created by M.T. using Adobe Photoshop software.

The proportion of KikGR-red CD103−DDCs in the dLN increased from 7.5% without tape stripping to 30% with tape stripping (Fig. 5D). A similar increase was observed even in the absence of OVA painting (Fig. 5E), indicating that tape stripping is the cause of increased CD103−DDC migration, regardless of the presence of exogenous antigen. Furthermore, although the total number of CD103−DDCs in the dLN did not change significantly between days one and three, 4-times more KikGR-red CD103−DDCs entered the dLN every 24 h after tape stripping, compared to the no-TS-d0PC control group (Fig. 5D; 7.5% vs. 29–30%). This result suggests that earlier migrants were lost and replaced by new migrants every 24 h.

Significant numbers of Alexa647+ skin-derived KikGR-green DCs were detected in dLNs from the d1PC and d2PC groups (Fig. 5; compare panels C and D). This population is likely to represent cells that departed the skin after OVA painting but prior to photoconversion, and which survived in the dLN until analysis. Alternatively, these cells may represent KikGR-green blood-bone precursors that migrate to the skin after photoconversion, take up Alexa647-OVA, then migrate to the dLN. These possibilities should be explored in future studies.

Taken together, our results demonstrate that tape stripping induces prolonged enhancement of CD103−DDC migration to and subsequent loss from the dLN, and accelerates the rate of exogenous protein trafficking from the skin to the dLN by CD103−DDCs (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Discussion

In the present study, we generated KikGR mice, which we used to visualize the in vivo dynamics of endogenous skin-derived DCs in the steady state, after chemical stress, and after mechanical injury. We show that the dLN is the final destination for DCs migrating from the skin, and that the lifespan of newly arrived CD103−DDCs within the dLN is only 2 days in the steady state (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S7). The loss of these cells from the dLN appears to occur by apoptotic cell death. Exogenous protein antigens are carried from the skin to the dLN immediately after mechanical injury, mainly by CD103−DDCs (Fig. 5 C and D). In addition, chemical stress and mechanical injury result in increased CD103−DDC migration from the skin to the dLN and the accelerated the loss of these cells from the dLN (Supplementary Fig. S7). In this way, CD103−DDCs are responsible for the rapid delivery of information about invading pathogens.

The kinetics of CD103−DDC accumulation in and loss from the dLN differed depending on the stressor. The induction of prominent but transient migration following skin irritant painting can be explained by the rapid maturation of DCs in the painted region of the skin. In contrast, mechanical injury, which results in disruption of the skin barrier and causes inflammation, is expected to accelerate monocyte influx into the injury site41, thus resulting in continuous and long-lasting enhancement of CD103−DDC migration to the dLN (Fig. 5).

In genetically modified mice that specifically express anti-apoptotic molecules in DCs, the lifespan of DCs is prolonged and systemic autoimmune disorders arise42,43. These observations suggest that appropriate levels of apoptosis among steady-state DCs are required for the maintenance of peripheral tolerance. An increase in the migration of DCs from peripheral tissues to the dLN during skin invasion, and the subsequent death of those migratory DCs in the dLN, would support immune homeostasis. This mechanism is also thought to play a role in the fine-tuning of T cell stimulation, because the rapid death of antigen-carrying DCs would limit the persistence of antigens within the LN and thus limit the duration of the T-cell response. The death of antigen-carrying skin-derived DCs would also be expected to accelerate antigen transfer to LN-resident DCs. The priming capability of CD103−DDCs in relation to CD4+ T cells is higher than for CD8+ T cells44, while CD8α+ LN-resident DCs are known to be effective antigen-presenting cells for CD8+ T cells3,44,45, with high phagocytic activity46. Thus, it is possible that the influx of a large number of apoptotic antigen-carrying CD103−DDCs triggers accelerated phagocytosis and cross priming by CD8α+ LN-resident DCs. Future studies should examine this possibility further.

In live virus vaccination, DCs carry the antigens of attenuated viruses to the dLNs in order to elicit protective immunity. On the other hand, in tumor vaccination, DCs carrying tumor antigens are adoptively transferred to stimulate tumor antigen-specific T cells in the dLNs47,48. Our findings suggest that the short lifespan of migratory DCs should be taken into account when considering strategies and clinical protocols for DC-based vaccination. To maximize the opportunity for the presentation of vaccine antigen to T cells by DCs, it would be beneficial to increase the retention time of antigen in the vaccination site using an appropriate adjuvant, which would promote the continuous capture and trafficking of vaccine antigens to the dLNs via migratory DCs. On the other hand, in order to promote the inter-DC transfer of vaccine antigens from migratory DCs to LN-resident DCs and subsequent antigen presentation, vaccine antigens should be optimized to increase their retention time and to increase the number of MHC products on the surface of LN-resident DCs49, which would result in more prolonged antigen presentation and thus more efficient T cell activation.

In conclusion, our study provides quantitative insights into the spatiotemporal changes that occur in skin-derived DC populations in the dLN under steady-state conditions and during the initiation of immune responses. We demonstrate that CD103−DDCs act as sentinels against skin invasion that respond with increased cellular migration and antigen trafficking from the skin to the dLNs. Combined techniques for tracking DC migration and monitoring antigen trafficking and presentation provide insights into DC dynamics that may lead to the development of novel strategies for immune regulation. KikGR mice, which facilitated the tracking of cell migration in vivo, offer a powerful tool for investigating immune regulation by revealing the spatiotemporal regulation of immune cells throughout the body.

Methods

Mice

To generate ROSA26-CAG-loxP-stop-loxP-KikGR knock-in mice, we inserted a CAG-loxP-stop-loxP-KikGR DNA construct into the ROSA26 locus of embryonic stem (ES) cells by homologous recombination. To construct the targeting vector, an additional chicken poly(A) sequence was inserted after the EGFP cDNA sequence in a CAG-stop-EGFP-targeting vector (kindly provided by Dr. Klaus Rajewsky, Immune Disease Institute, Harvard Medical School), then we replaced the cDNA of EGFP with that of KikGR33. The targeting vector was electroporated into mouse ES cells (B6 × 129+Ter/SvJcl) and positive cell clones were identified by PCR. The mutated ES cell clones were microinjected into C57BL/6 blastocysts to generate chimeras, and then backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice. Germline transmission was verified using PCR. KikGR mice for experiments were generated by mating the ROSA26-CAG-loxP-stop-loxP-KikGR mice with CAG-Cre mice50 (kindly provided by Dr. Jun-ichi Miyazaki, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan) and then backcrossing the offspring with C57BL/6 mice at least six times. KikGR CCR7–/– mice were generated by mating CCR7–/– mice36 (kindly provided by Dr. Martin Lipp, MDC, Berlin, Germany) with KikGR mice. C57BL/6 mice were purchased from CLEA Japan. Mice were bred and maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility at Kyoto University. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines of the Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University, using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Photoconversion

Photoconversion of the LN and skin of KikGR mice was performed as described previously30,32,51. Briefly, KikGR mice were anesthetized and the abdominal skin was exposed to violet light for 2 min (95 mW/cm2 from USHIO SP500 spot UV curing equipment with a 436 nm bandpass filter). Violet light (436 nm) was used to avoid causing inflammation or other immunomodulatory effects, which may be induced by exposure to shorter wavelengths. Exposure to violet light (10 min) does not induce inflammation or immunomodulation, based on assessment of Con A-induced T cell proliferation in vitro30 and IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA expression in the skin in vivo32.

Bone marrow-chimeric mice

KikGR or wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice were lethally irradiated (9.25 Gy) before intravenous injection (107 cells) of bone marrow (BM) cells from WT or KikGR mice. Experiments were not conducted until at least six weeks after BM cell transfer to allow for reconstitution of immune cells in peripheral tissues. At this stage, hematopoietic chimerism (determined as the proportion of lymph node B cells that expressed KikGR) exceeded 98%. BM chimeras in which KikGR mice were reconstituted with BM cells from WT mice (WT BM→KikGR) were used to detect and analyze radioresistant LCs, while KikGR BM→WT chimeras were used to facilitate the histological visualization of KikGR in hematopoietic cells.

Histological analysis

Because the strong KikGR signal from stromal cells in KikGR mice makes difficult the detection of KikGR signal from hematopoietic cells, KikGR BM→WT chimeras were used to facilitate the visualization of KikGR by histological analysis. The abdominal skin of KikGR-BM→WT mice was subjected to photoconversion with or without skin irritant painting. Twenty-four hours after photoconversion, the axillary LNs were dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Wako Chemicals), then placed in 30% sucrose as a cryoprotectant. Frozen tissue sections were prepared and observed using a LSM-710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Reagents, antibodies, and flow cytometric analysis

Cell suspensions from the epidermis and dermis were prepared as described previously32, then stained with anti-CD45 microbeads and enriched for CD45+ cells by magnetically activated cell sorting (Miltenyi Biotec). Cell suspensions from the LNs were prepared as described previously30,31,32. Fluorochrome-conjugated or biotinylated anti-mouse CD3, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, CD45, CD103, CD326, MHC class II (I-A, M5/115) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and Annexin V were purchased from BD, eBioScience, or BioLegend. The Pacific Orange-conjugated anti-mouse MHC class II (I-A, M5/115) mAb was prepared using an antibody labeling kit (Life Technologies). Caspase activity was assessed using a FLICA Poly Caspases assay kit (Immunochemistry Technologies). For flow cytometric analysis, cells were washed with Dulbecco's PBS containing 2% FCS and 0.02% sodium azide. Next, cells were incubated with 2.4G2 hybridoma culture supernatant to block Fc binding, then stained with biotinylated mAbs followed by APC-conjugated streptavidin or fluorochrome-labeled mAbs. Dead cells were labeled with 7-amino-actinomycin D (BioLegend). For the detection of cleaved caspase-3, cells were incubated with 2.4G2 hybridoma culture supernatant, stained with fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs, fixed with Fixation buffer (BioLegend), permeabilized with Permeabilization Wash buffer (BioLegend), then stained with anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175; Cell Signaling) or isotype control antibodies followed by fluorochrome-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Life Technologies). Stained samples were analyzed using a Fortessa flow cytometer (BD). KikGR green and red signals were detected using 530/60 and 595/50 bandpass filters, respectively. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using Flowjo software (Tree Star).

Skin irritant painting, tape stripping, and protein application experiments

In skin irritant painting experiments, 50 μL of a 1:1 acetone (Wako Chemicals):dibutylphthalate (Sigma-Aldrich) mixture was painted onto clipped abdominal skin. In tape-stripping experiments, adhesive tape (Scotch) were applied and removed from clipped abdominal skin 10 times in succession. In protein application experiments, 10 μL of Alexa 647-conjugated OVA (Invitrogen; 10 mg/mL in Dulbecco's PBS) was applied to a 2-cm diameter region of the dorsal skin.

Calculation of the lifespan of skin-derived DC subsets in the dLN using an exponential line-fitting model

Exponential line-fitting based on the decrease in the number of KikGR-red skin-derived DCs in the inguinal LN following photoconversion was used to calculate T50, T90 and T95 (the time for 50%, 90% and 95% of cells to be replaced, respectively). It was assumed that the age distribution within each experimental group was homogenous.

Author Contributions

M.T. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; A.H., S.M., Y.N., R.I. and H.T. performed research and analyzed data; and S.U., F.H.W.S., K.I., K.M., A.M., K.K., T.W. and O.K. designed research and wrote the paper.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures

Acknowledgments

We thank Ami Kyusai for performing part of the flow cytometric analysis. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (#22590442); for Scientific Research in Innovative Areas “Fluorescence Live Imaging” (#23113506) and “Analysis and Synthesis of Multidimensional Immune Organ Network” (#24111007) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology; Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology of the Japanese Government; Astellas Pharma Inc. through the Formation of Innovation Centers for the Fusion of Advanced Technologies Program; and by grants from the Sumitomo Science Foundation.

References

- Banchereau J. & Steinman R. M. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392, 245–252 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba K. et al. Efficient presentation of phagocytosed cellular fragments on the major histocompatibility complex class II products of dendritic cells. J Exp Med 188, 2163–2173 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan R. S. et al. Migratory dendritic cells transfer antigen to a lymph node-resident dendritic cell population for efficient CTL priming. Immunity 25, 153–162 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleeton M. N. et al. Peyer's patch dendritic cells process viral antigen from apoptotic epithelial cells in the intestine of reovirus-infected mice. J Exp Med 200, 235–245 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belz G. T. et al. The CD8alpha(+) dendritic cell is responsible for inducing peripheral self-tolerance to tissue-associated antigens. J Exp Med 196, 1099–1104 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belz G. T. et al. Cutting Edge: Conventional CD8{alpha}+ Dendritic Cells Are Generally Involved in Priming CTL Immunity to Viruses. J Immunol 172, 1996–2000 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belz G. T. et al. Distinct migrating and nonmigrating dendritic cell populations are involved in MHC class I-restricted antigen presentation after lung infection with virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 8670–8675 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst P. & Brocker T. Endogenous dendritic cells are required for amplification of T cell responses induced by dendritic cell vaccines in vivo. J Immunol 170, 2817–2823 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath W. R. & Carbone F. R. Dendritic cell subsets in primary and secondary T cell responses at body surfaces. Nat Immunol 10, 1237–1244 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henri S. et al. Disentangling the complexity of the skin dendritic cell network. Immunol Cell Biol 88, 366–375 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seneschal J. et al. Human epidermal Langerhans cells maintain immune homeostasis in skin by activating skin resident regulatory T cells. Immunity 36, 873–884 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursch L. S. et al. Identification of a novel population of Langerin+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med 204, 3147–3156 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginhoux F. et al. Blood-derived dermal langerin+ dendritic cells survey the skin in the steady state. J Exp Med 204, 3133–3146 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin L. F. et al. The dermis contains langerin+ dendritic cells that develop and function independently of epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med 204, 3119–3131 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itano A. A. et al. Distinct Dendritic Cell Populations Sequentially Present Antigen to CD4 T Cells and Stimulate Different Aspects of Cell-Mediated Immunity. Immunity 19, 47–57 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misslitz A. C. et al. Two waves of antigen-containing dendritic cells in vivo in experimental Leishmania major infection. Eur J Immunol 34, 715–725 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissenpfennig A. et al. Dynamics and Function of Langerhans Cells In Vivo: Dermal Dendritic Cells Colonize Lymph Node AreasDistinct from Slower Migrating Langerhans Cells. Immunity 22, 643–654 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh K. Y., Tsai C. C., Herbert Wu C. H. & Lin R. H. Epicutaneous exposure to protein antigen and food allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 33, 1067–1075 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster R., Braun A. & Worbs T. Lymph node homing of T cells and dendritic cells via afferent lymphatics. Trends in Immunol 33, 271–280 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson G. G., Fossum S. & Harrison B. Properties of lymph-borne (veiled) dendritic cells in culture. II. Expression of the IL-2 receptor: role of GM-CSF. Immunology 68, 108–113 (1989). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuno K., Kudo S., Ezaki T. & Miyakawa K. Isolation of dendritic cells in the rat liver lymph. Transplantation 60, 765–768 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh C. W., MacPherson G. G. & Steer H. W. Characterization of nonlymphoid cells derived from rat peripheral lymph. J Exp Med 157, 1758–1779 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruedl C. et al. Anatomical Origin of Dendritic Cells Determines Their Life Span in Peripheral Lymph Nodes. J Immunol 165, 4910–4916 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath A. T. et al. Developmental kinetics and lifespan of dendritic cells in mouse lymphoid organs. Blood 100, 1734–1741 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merad M. et al. Langerhans cells renew in the skin throughout life under steady-state conditions. Nat Immunol 3, 1135–1141 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogunovic M. et al. Identification of a radio-resistant and cycling dermal dendritic cell population in mice and men. J Exp Med 203, 2627–2638 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K. et al. Origin of dendritic cells in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. Nat Immunol 8, 578–583 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merad M. & Manz M. G. Dendritic cell homeostasis. Blood 113, 3418–3427 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macatonia S. E. et al. Localization of antigen on lymph node dendritic cells after exposure to the contact sensitizer fluorescein isothiocyanate. Functional and morphological studies. J Exp Med 166, 1654–1667 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomura M. et al. Monitoring cellular movement in vivo with photoconvertible fluorescence protein "Kaede" transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 10871–10876 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomura M., Itoh K. & Kanagawa O. Naive CD4+ T lymphocytes circulate through lymphoid organs to interact with endogenous antigens and upregulate their function. J Immunol 184, 4646–4653 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomura M. et al. Activated regulatory T cells are the major T cell type emigrating from the skin during a cutaneous immune response in mice. J Clin Invest 120, 883–893 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui H. et al. Semi-rational engineering of a coral fluorescent protein into an efficient highlighter. EMBO Rep 6, 233–238 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotani M. et al. Systemic circulation and bone recruitment of osteoclast precursors tracked by using fluorescent imaging techniques. J Immunol 190, 605–612 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clydesdale G. J., Dandie G. W. & Muller H. K. Ultraviolet light induced injury: Immunological and inflammatory effects. Immunol Cell Biol 79, 547–568 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster R. et al. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell 99, 23–33 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohl L. et al. CCR7 Governs Skin Dendritic Cell Migration under Inflammatory and Steady-State Conditions. Immunity 21, 279–288 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henri S. et al. CD207+ CD103+ dermal dendritic cells cross-present keratinocyte-derived antigens irrespective of the presence of Langerhans cells. J Exp Med 207, 189–206 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph G. J., Angeli V. & Swartz M. A. Dendritic-cell trafficking to lymph nodes through lymphatic vessels. Nat Rev Immunol 5, 617–628 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streilein J. W., Lonsberry L. W. & Bergstresser P. R. Depletion of epidermal langerhans cells and Ia immunogenicity from tape-stripped mouse skin. J Exp Med 155, 863–871 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao K. et al. Stress-induced production of chemokines by hair follicles regulates the trafficking of dendritic cells in skin. Nat Immunol 13, 744–752 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. et al. Dendritic cell apoptosis in the maintenance of immune tolerance. Science 311, 1160–1164 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Huang L. & Wang J. Deficiency of Bim in dendritic cells contributes to overactivation of lymphocytes and autoimmunity. Blood 109, 4360–4367 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedoui S. et al. Cross-presentation of viral and self antigens by skin-derived CD103+ dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 10, 488–495 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Haan J. M., Lehar S. M. & Bevan M. J. CD8(+) but not CD8(-) dendritic cells cross-prime cytotoxic T cells in vivo. J Exp Med 192, 1685–1696 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyoda T. et al. The CD8+ dendritic cell subset selectively endocytoses dying cells in culture and in vivo. J Exp Med 195, 1289–1302 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuyaerts S. et al. Current approaches in dendritic cell generation and future implications for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer immunol immun: CII 56, 1513–1537 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergati M. et al. Strategies for cancer vaccine development. J biomed biotech 10.1155/2010/596432 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Lugt B. et al. Transcriptional programming of dendritic cells for enhanced MHC class II antigen presentation. Nat Immunol 15, 161–167 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K., Mitani K. & Miyazaki J. Efficient regulation of gene expression by adenovirus vector-mediated delivery of the CRE recombinase. Biochem biophys res comm 217, 393–401 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomura M. & Kabashima K. Analysis of cell movement between skin and other anatomical sites in vivo using photoconvertible fluorescent protein "Kaede"-transgenic mice. Methods in mol biol 961, 279–286 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures