Abstract

More than 50% of the world population is infected with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). The bacterium highly links to peptic ulcer diseases and duodenal ulcer, which was classified as a group I carcinogen in 1994 by the WHO. The pathogenesis of H. pylori is contributed by its virulence factors including urease, flagella, vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), cytotoxin-associated gene antigen (Cag A), and others. Of those virulence factors, VacA and CagA play the key roles. Infection with H. pylori vacA-positive strains can lead to vacuolation and apoptosis, whereas infection with cagA-positive strains might result in severe gastric inflammation and gastric cancer. Numerous medicinal plants have been reported for their anti-H. pylori activity, and the relevant active compounds including polyphenols, flavonoids, quinones, coumarins, terpenoids, and alkaloids have been studied. The anti-H. pylori action mechanisms, including inhibition of enzymatic (urease, DNA gyrase, dihydrofolate reductase, N-acetyltransferase, and myeloperoxidase) and adhesive activities, high redox potential, and hydrophilic/hydrophobic natures of compounds, have also been discussed in detail. H. pylori-induced gastric inflammation may progress to superficial gastritis, atrophic gastritis, and finally gastric cancer. Many natural products have anti-H. pylori-induced inflammation activity and the relevant mechanisms include suppression of nuclear factor-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway activation and inhibition of oxidative stress. Anti-H. pylori induced gastric inflammatory effects of plant products, including quercetin, apigenin, carotenoids-rich algae, tea product, garlic extract, apple peel polyphenol, and finger-root extract, have been documented. In conclusion, many medicinal plant products possess anti-H. pylori activity as well as an anti-H. pylori-induced gastric inflammatory effect. Those plant products have showed great potential as pharmaceutical candidates for H. pylori eradication and H. pylori induced related gastric disease prevention.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Virulence factor, Medicinal plant, Active compound, Mechanism, Inflammation, Gastric cancer, Nuclear factor-κB pathway

Core tip: Many medicinal plant products possess anti-Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) activity as well as an anti-H. pylori induced gastric inflammatory effect. Those plant products have showed great potential as pharmaceutical candidates for H. pylori eradication and H. pylori induced related gastric disease prevention.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a spiral-shaped, Gram-negative, microaerophilic bacterium with 4 to 6 flagalla whose ecological niche is the human stomach. The bacterium was first isolated from the gastric mucosa of gastritis patients by Marshall and Warren in 1983[1]. More than 50% of the world population is infected with H. pylori. The bacterium highly links to peptic ulcer diseases (PUD) and duodenal ulcers. Ten to fifty percent of infected individuals develop PUD, and 1%-3% of PUD patients progress to gastric cancer[2]. The gastric cancer risk in H. pylori-infected people was 2 to 7 times of that of the uninfected. Over half of gastric cancer patients have associated H. pylori infection[3,4]. The WHO classified H. pylori as a group I carcinogen in 1994[3].

VIRULENCE FACTORS OF H. PYLORI

The pathogenesis of H. pylori is caused by its virulence factors shown in Table 1. Those virulence factors are responsible for H. pylori colonization [urease, flagella, and blood-group-antigen-binding adhesion (BabA)] and survival [NADPH oxidase 1 (Nox1), superoxide dismutase, catalase, phospholipase A, alcohol dehydrogenase] as well as infected tissue inflammation and even damage [Vac A, Cag A, outer inflammatory protein A (OipA), duodenal ulcer promoting A (DupA), H. pylori neutrophil activation protein (HP-NAP), Lewis x and y antigens, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)][4-7]. Of those virulence factors, VacA and CagA play the key roles.

Table 1.

| Virulence factor | Function |

| H. pylori colonization | |

| Urease | Buffers stomach acid, toxic effect on epithelium cells, disrupting cell tight junctions, and sheathing antigen |

| Flagella | Active movements through mucin |

| BabA | Adhesin |

| H. pylori survival | |

| Nox1 | Resistance to killing by phagocytes, infected-site inflammation |

| Superoxide dismutase | Resistance to killing by phagocytes |

| Catalase | Resistance to killing by phagocytes |

| Phospholipase A | Digest phospholipids in cell membranes |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase | Gastric mucosal injury |

| Tissue inflammation and damage | |

| Vac A | Cytotoxicity |

| cag PAI | 31 genes coding for type IV secretion system |

| CagA | Immunodominant antigen (part of cag PAI) |

| OipA | Induce inflammation, especially for IL-8 |

| DupA | Induce inflammation via CagA, OipA and/or VacA |

| HP-NAP | Neutrophil activation |

| Lewis x and y antigens | Molecular mimicry, autoimmunity |

| LPS | Low toxicity |

| Other | |

| IceA | Homolog of type II restriction endonuclease |

H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; BabA: Blood-group-antigen-binding adhesion; CagA: Cytotoxin associated gene antigen; DupA: Duodenal ulcer promoting A; HP-NAP: H. pylori neutrophil activation protein; IceA: Induced by contact with epithelium factor antigen; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; Nox1: NADPH oxidase 1; OipA: Outer inflammatory protein A; Vac A: Vacuolating cytotoxin A; IL: Interleukin.

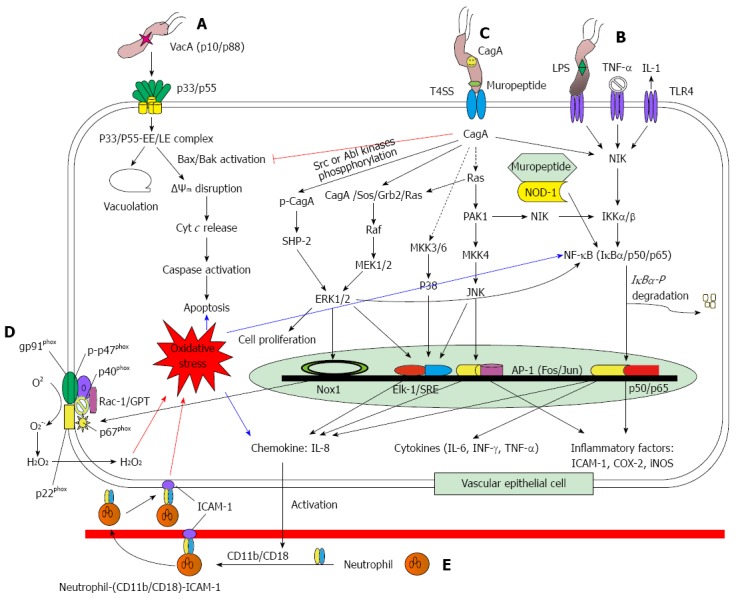

VacA

The vacA gene (3.9 kb) encodes the VacA protein and is present in all H. pylori strains. The protoxin of VacA is initially a 140 kDa protein, which undergoes both N-terminal and C-terminal cleavages to yield an N-terminal signal sequence (33 residues), a mature 88-kDa secreted toxin (p88), a small secreted peptide with unknown function, and a C-terminal autotransporter domain. The signal sequence is characterized by allelic variation with s1a, s1b, and s2, which contributes to the recognization of the inner membrane receptor of target cells. The mature p88 divides into subunits N-terminal 33 kDa (p33) and a C-terminal 55 kDa (p55) with noncovalent bonding. The N-terminal 32 hydrophobic residues of p33 play a key role in cytoplasmic membrane insertion, and p55 is essential for the toxin to bind to the plasma membrane. The p55 is also an allelic variation with m1 and m2. The strains with vacA s1/m1 alleles are more strongly associated with gastric epithelial damage and gastric ulcers[5,8-13]. As shown in Figure 1A, oligomer p88 forms anion-selective channels in the cytoplasmic membrane, which can further react with early and late endosomal compartments (EE/LE) to form anion-selective channels in the vacuole membrane. Such channels increase permeability to small organic molecules and cations Fe3+/Ni2+ which can further interact with NH4+ from H. pylori generating an osmotic force for the driving water influx and vesicle swelling, and finally leads vacuolation[5,8-12]. On the other hand, the p88/EE/LE complex could be activated by Bax and Bak, resulting in mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm) disruption, followed by the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to cytoplasm, activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3, and finally proceeding to apoptosis[10-12,14-17]. However, that apoptosis is inhibited by CagA (Figure 1C)[11,14,18].

Figure 1.

Signal transduction and immune response in Helicobacter pylori infected gastric epithelial cells. A: VacA-induced apoptosis; B: NF-κB pathway; C: Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway; D: Nox-1 pathway; E: IL-8/neutrophil pathway[5,8-12,14-17,19,25-39]. LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; IL: Interleukin; TLR4: Toll-like receptor 4; NF-κB: Nuclear factor-kappaB; NIK: NF-κB-inducing kinase; VacA: Vacuolating cytotoxin A; CagA: Cytotoxin-associated gene antigen; PAK1: p21-activated kinase; IKKα/β: IκB kinase α/β; MAPK: Mitogen-activated protein kinase; MKK4: MAPK kinase 4; MEK1/2: MAPK/ERK kinase 1/2; INF-γ: Interferon-γ; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; NOD1: Nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain protein 1; COX-2: Cyclooxygenase-2; ICAM-1: Intercellular adhesion molecule-1; iNOS: Inducible nitric oxide synthase.

CagA

Cag A, a 120 to 145 KDa protein, is encoded on the cag pathogenicity island (cag PAI) which is a 40 kb locus (containing 31 genes) that encodes for a type IV secretion system (T4SS), and is the only known effector protein to be injected into host cells[4,12,19,20]. Infection with cagA positive H. pylori strains has a high rate of severe gastric inflammation, gastritis, atrophic gastritis, and gastric adenocarcinoma[3,4,12,19-24]. Approximately 60%-70% of isolates are cagA positive. However, this rate varies geographically, to nearly 100% for East Asian countries and 60% for Western patients[4,21].

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway: Cag A is a multiple effector via phosphorylation independent and dependent pathways (Figure 1B and C). Once H. pylori adheres to the host’s gastric epithelial cells, CagA is injected into cytosol through T4SS to activate NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) and IκB kinase α/β (IKKα/β) resulting in subunit IκBα of NF-κB (trimer IκBα/p50/p60) phosphorylation and then degradation[8,12,19,25-28]. Active NF-κB (dimer p50/p60) translocates into the nucleus to transcribe the inflammatory factor genes [cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)], proinflammatory cytokine genes [interleukin-6 (IL-6), interferon-γ (INF-γ), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)], and chemokine IL-8 gene[8,19,25,27,29-31]. This is called the NF-κB pathway (Figure 1B). All of those related proteins can result in severe inflammation for infected cells. H. pylori muropeptide can also enter into cytosol through T4SS to bind with nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain protein 1 (NOD1), and thereafter activates NF-κB[12,28,29]. On the other hand, H. pylori LPS, TNF-α, and IL-1 can enter into cell cytosol via toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) to initiate the NF-κB pathway (Figure 1B)[19,25,27,29,30].

Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (MAPK): Aside from the NF-κB pathway, MAPK pathway activation is induced by CagA (Figure 1C). MAPK concerns three key kinases: C-terminal Jun-kinase (JNK), extracellular signal regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), and p38 kinase, for which the JNK pathway involves p21-activated kinase (PAK1), mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase 4 (MKK4), and JNK; the p38 pathway involves MAP kinase 3/6 (MKK3/6) and p38; and the MEK/ERK pathway involves complex CagA/son of sevenless/growth factor receptor bound 2/rat sarcoma (CagA/Sos/Grb2/Ras), Raf, MAPK/ERK kinase 1/2 (MEK1/2), and ERK1/2. The MAPK cascades lead to transcription factor [activator protein 1 (AP-1), Elk-1/serum response element (Elk-1/SRE), Nox1, and NF-κB] activation, leading to translation of chemokine IL-8, cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, INF-γ), and inflammatory factors (COX-2, ICAM-1, and iNOS) as well as NADPH oxidase activation[27-29,31-35].

Nox-1 pathway: The Nox-1 family consists of members gp91phox, p22phox, p47phox, p67phox, and p40phox, in which gp91phox and p22phox persist in cytosol, and p40phox, p47phox, and p67phox are located in the cell membrane[36,37]. When a host cell is attacked by H. pylori, p47phox is immediately phosphorylated (p-p47) along with p67phox, p40phox, and GTPase-Rac to translocate to the cell membrane to form a gp91phox/p22phox/p-p47phox/p67phox/p40phox/GTPase-Rac complex, an active NADPH oxidase. Active p67phox oxidizes NADPH to NADP+ and H+ which pass through gp91phox and are released to the environment; at the same time, gp91phox reduces O2 to O2-. and follows hydrogen peroxide production, resulting in oxidative stress in the H. pylori infected cells (Figure 1D)[33,35,38,39].

SHP-2/ERK pathway~CagA phosphorylation dependent: With exception to the CagA independent pathway, CagA can suffer phosphorylation by Src and Ab1 kinases, and then forms a complex with Src homology 2 (SH2)-domain containing protein tyrosine phosphatase (SHP-2) to activate ERK1/2 (Figure 1C). Both MEK/ERK and SHP-2/ERK pathways not only lead to NF-κB (Figure 1B) and Nox1 (Figure 1D) activation, but also result in cell proliferation (Figure 1C)[12,19-21,28,29].

IL-8

As aforementioned, IL-8 is a chemokine which is regulated by the transcription factors NF-κB, AP-1, and Elk/SRE. IL-8 plays a key role in H. pylori infection and is an important feature in H. pylori-infected patients. As shown in Figure 1E, IL-8 infiltrates into vascular endothelial cells to activate the CD11b/CD18 dimer. The active CD11b/CD18 dimer forms a complex with neutrophil (CD11b/CD18/neutrophil), and then further binds to ICAM-1 on the vascular endothelial cell membrane (CD11b/CD18/neutrophil/ICAM-1). That tetramer (CD11b/CD18/neutrophil/ICAM-1) infiltrates into gastric epithelial cells and releases high amounts of ROS (O2-., H2O2, HOCl, OH•, and 1O2) through neutrophil NADPH oxidase, resulting in oxidative burst[27,29,33,40]. Additionally, IL-8 can activate polymorphonuclear cells and/or macrophages to produce IL-12 which further amplifies the T-cell response to H. pylori[29].

ANTI-H. PYLORI ACTIVITY OF MEDICINAL PLANTS

Various pharmacological regimens have been studied in the treatment of H. pylori infection. Antibiotics[41,42], proton-pump inhibitors[43,44], H2-blockers[45,46], and bismuth salts[47] are suggested standard treatment modalities, which are typically combined in dual, triple, and quadruple therapy regimens in order to eradicate H. pylori infection[41,48]. Some problems may arise upon administration of those eradication regimens, i.e. the cost[48], the efficacy of antibiotics regarding the pH (for instance, amoxicillin is most active at a neutral pH and tetracycline has greater activity at a low pH)[48] and resistance to the antibiotics[49-51]. Therefore, some patients undergoing such drug regimens experienced therapeutic failure.

Plant extracts and fractions

Numerous studies have been carried out to investigate the anti-H. pylori activity of plant extracts, partially purified fractions, natural compounds, and synthetic compounds. Anti-H. pylori activity for the medicinal plant extracts and partially purified fractions is listed in Table 2, which has those results categorized as 4 classes according to their minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC): (1) strong activity (MIC: < 10 μg/mL); (2) strong-moderate activity (MIC: 10-100 μg/mL); (3) weak-moderate activity (MIC: 100-1000 μg/mL); and (4) weak activity (MIC: >1000 μg/mL). In Table 2, 34 studies including more than 80 plants were collected. Surprisingly, only a few studies exhibited strong (2.9%, 1/34)[52] and strong-moderate (11.8%, 4/34)[53-57] activity. Most studies revealed weak-moderate (50%, 17/34)[58-73] and weak (32.4%, 11/34)[74-81] activity against H. pylori. Notably, a few plant extracts possessed strong anti-H. pylori activity. The greatest of them was Impatiens balsamina L. (Balsaminaceae), a Taiwanese folk medicinal plant. The acetone, 95% ethanol, and ethyl acetate pod extracts showed strong anti-H. pylori activity with 1.25-2.5 μg/mL of MICs and 1.25-5.0 μg/mL of minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) against multiple-antibiotic [clarithromycin (CLR), metronidazole (MTZ), and levofloxacin (LVX)] resistant H. pylori strains. Such activity exceeded that of MTZ and approximated that of amoxicillin (AMX), one of the most effective drugs used in the eradication of H. pylori infection worldwide[52]. The Persea Americana Mill. (Lauraceae), a Mexican medicinal plant, in methanol extract also showed strong anti-H. pylori activity with < 7.5 μg/mL of MIC[53]. Remarkable anti-H. pylori activity was reported for three Paskin indigenous medicinal plant extracts: the Acacia nilotica (L.) Delile (Fabaceae) aqueous extract, the Fagonia arabica L. (Zygophyllaceae) acetone extract, and the Casuarina equisetifolia L. (Casuarinaceae) methanol extract, all of them having 8 μg/mL of MIC[61]. The chloroform fractions from the methanol extracts of Centaurea solstitialis ssp. Solstitialis and Centaurea solstitialis ssp. solstitialis (flowers) also exhibited significantly lower MIC (1.95 μg/mL) against H. pylori, both plants having been used as Turkish anti-ulcerogenic folk remedies[59]. The leaf hexane fraction of Aristolochia paucinervis Pomel, a Moroccan medicinal plant, demonstrated higher inhibitory activity (MIC: 4 μg/mL) against H. pylori[58].

Table 2.

Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of medicinal plant extracts and fractions

| Plant | Test sample | MIC/MBC | Ref. |

| Strong activity (MIC: < 10 μg/mL) | |||

| Impatiens balsamina L. | Pod acetone/95% ethanol/ | MIC: 0.625-2.5 μg/mL | Wang et al[52] |

| ethyl acetate extracts | MBC: 1.25-2.5 μg/mL | ||

| Strong-moderate acticity (MIC: 10-100 μg/mL) | |||

| Persea americana, Annona cherimola, Guaiacum coulteri, Moussonia deppeana | Methanol extract | MIC: 7.5-15.6 μg/mL | Castillo-Juárez et al[53] |

| Myristica fragrans (seed), Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary leaf ) | Methanol extract | MIC: 12.5-25 μg/mL | Mahady et al[54] |

| Curcuma amada Roxb., Mallotus phillipinesis (Lam) Muell., Myrisctica fragrans Houtt., Psoralea corylifolia L. | 70% Ethanol extract | MIC: 15.6-62.5 μg/mL | Zaidi et al[55] |

| Achillea millefolium, Foeniculum vulgare (seed), Passiflora incarnata (herb), Origanum majorana (herb) and a (1:1) combination of Curcuma longa (root), ginger rhizome | Methanol extract | MIC: 50 μg/mL | Mahady et al[54] |

| Carum carvi (seed), Elettaria cardamomum (seed), Gentiana lutea (roots), Juniper communis (berry), Lavandula angustifolia (flowers), Melissa officinalis (leaves), Mentha piperita (leaves), Pimpinella anisum (seed) | Methanol extract | MIC: 100 μg/mL | Mahady et al[54] |

| Abrus cantoniensis, Saussurea lappa, Eugenia caryophyllata | Ethanol extract | MIC: 40 μg/mL | Li et al[56] |

| Hippophae rhamnoides, Fritillaria thunbergii, Magnolia officinalis, Schisandra chinensis, Corydalis yanhusuo, Citrus reticulata, Bupleurum chinense, Ligusticum chuanxiong | Ethanol extract | MIC: 60 μg/mL | Li et al[56] |

| Myroxylon peruiferum | Methanol extract | MIC: 62.5 μg/mL | Ohsaki et al[57] |

| Weak-moderate acticity (MIC: 100-1000 μg/mL) | |||

| Aristolochia pauciner6is | Rhizome/leave fraction | MIC: 4-128 μg/mL | Gadhi et al[58] |

| Cistus laurifolius, Spartium junceum, Cedrus libani, solstitialis, Momordica charantia, Sambucus ebulus, Hypericum perforatum | Solvent extract and hexane fraction | MIC: 1.95-250 μg/mL | Yeşilada et al[59] |

| Larrea divaricate Cav (leaves and tender branches) | Aqueous extract | MIC: 40-100 μg/mL | Stege et al[60] |

| Acacia nilotica (L.) Delile, Calotropis procera (Aiton) | Methanol/acetone extract | MIC: 8-256 μg/mL | Amin et al[61] |

| W.T. Aiton, Fagonia arabica L., Adhatoda vasica Nees, Casuarina equisetifolia L. | |||

| Zingiber officinale | 95% Ethanol extract | MIC: 10-160 μg/mL | Nostro et al[62] |

| Tephrosia purpurea (Linn.) Pers. | Methanol extract and fraction | MIC: 25-400 μg/mL | Chinniah et al[63] |

| Terminalia macroptera (root) | Root solvent fraction | MIC: 100-200 μg/mL | Silva et al[64] |

| Black myrobalan (Teminalia chebula Retz) | Water extract | MIC: 125 μg/mL | Malekzadeh et al[65] |

| MBC: 150 μg/mL | |||

| Rubus ulmifolius leaves | Ethyl acetate/methanol | MIC: 134-270 μg/mL | Martinia et al[66] |

| Amphipterygium adstringens | Bark petroleum ether fraction | MIC: 160 μg/mL | Castillo-Juárez et al[67] |

| Lycopodium cernuum | Hexane fraction | MIC: 16-1000 μg/mL | Ndip et al[68] |

| MBC: 125-1000 μg/mL | |||

| Ageratum conyzoides, Scleria striatinux, Lycopodium cernua | Methanol extract | MIC: 63-1000 μg/mL | Ndip et al[69] |

| MBC: 195-15000 μg/mL | |||

| Sclerocarya birrea | Acetone/aqueous stem bark extract | MIC: 80-2500 μg/mL | Njume et al[70] |

| Including Artemisia ludoviciana subsp.mexicana 43 plants | Methanol/aqueous extract | MIC: 312-500 μg/mL | Castillo-Juárez et al[53] |

| Pteleopsis suberosa | Stem bark methanol extract | MIC: 313-500 μg/mL | Germanò et al[71] |

| Ageratum conyzoides, Scleria striatinux, Lycopodium cernua | Methanol extract | MIC: 32-1000 μg/mL | Ndip et al[69] |

| Including Cuminum cyminum L., Cynara scolymus L., Origanum vulgare L. 17 plants | Ethanol extracts | MIC: 600-10000 μg/mL | Nostro et al[72] |

| Allium sativum | Aqueous extract | MIC: 2000-5000 μg/mL | Cellini et al[73] |

| Weak acticity (MIC: > 1000 μg/mL) | |||

| Mentha × piperita, Peppermint Oil, Origanum vulgare, Pimpinella anisum, Aniseed Oil, Syzygium aromaticum | Essential oil | IC50: 160-1460 μg/mL | Cwikla et al[74] |

| Chamomila recutita L., Ilex paraguariensis A. St.-Hil. | 96% Ethanol extract | MIC: < 625-1250 μg/mL | Cogo et al[75] |

| Allium ascalonicum Linn. (leaf) | Methanol extract | MIC: 625- 1250 μg/mL | Bolanle et al[76] |

| Sclerocarya birrea | Stem bark acetone/aqueous extracts | MIC90: 60-2500 μg/mL | Njume et al[70] |

| Punica granatum, Quercus infectoria | Ethanol extract | MIC: 160-> 2500 μg/mL | Voravuthikunchai et al[77] |

| Mentha × piperita, Peppermint Oil, Origanum vulgare, Pimpinella anisum, Aniseed Oil, Syzygium aromaticum | Essential oil | IC50: 160-1460 μg/mL | Cwikla et al[74] |

| Including Anthemis melanolepis 13 plants | 70% Methanol extract | MIC: 625-5000 μg/mL | Stamatis et al[78] |

| Including Cuminum cyminum L. 17 plants | Ethanol extract | MIC: 75-10000 μg/mL | Nostro et al[72] |

| Plumbago zeylanica L. | Acetone extract | MIC: 320-10240 μg/mL | Wang and Huang[79] |

| MBC: 5120-81920 μg/mL | |||

| Anisomeles indica (L.) O. Kuntze, Alpinia speciosa (Wendl.) K. Schum., Bombax malabaricum DC., Paederia scandens (Lour.) Merr. | 95% Ethanol extract | MIC: 640-10240 μg/mL | Wang and Huang[80] |

| Allium sativum | Aqueous extract | MIC: 0.1% (v/v) | Cellini et al[73] |

| Including Cymbopogon citratus (lemongrass) 13 plants | Essential oil | Ohno et al[81] | |

MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration; MBC: Minimum bactericidal concentration.

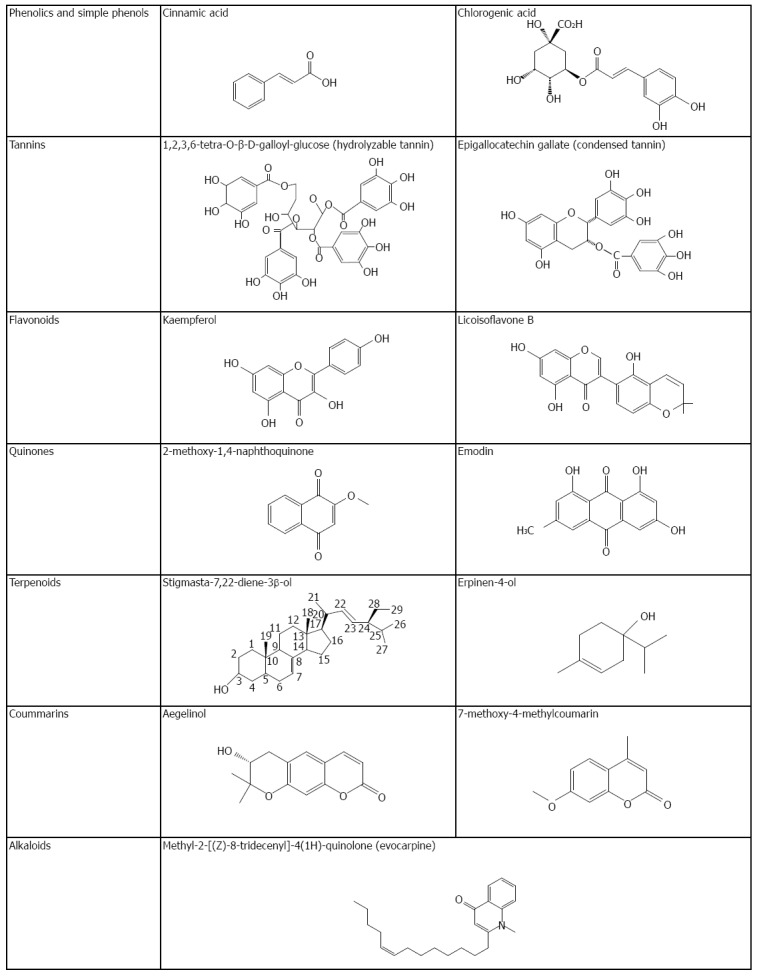

Natural compounds from plants

Aside from plant extracts, much literature has reported on the anti-H. pylori activity of plant compounds. Table 3 lists 28 studies including 131 compounds to address their anti-H. pylori activity in which phenolics/simple phenols/polyphenols, flavonoids, quinones, coumarins, terpenoids, alkaloids, and other compounds are involved. Some of these compounds’ chemical structures are shown in Figure 2. Notably, MICs for those compounds were much lower than those of plant extracts (Table 2), over 50% of which being lower than 10 μg/mL. Specifically, of those compounds, 5 compounds [2-methoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (MeONQ)[95], terpinen-4-ol[106], pyrrolidine[106], 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-8-tridecenyl]-4-(1H)-quinolone[107], and 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-7-tridecenyl]-4-(1H)-quinolone[107]] of MICs or 50% MICs (MIC50) were lower than 1 μg/mL, which were similar to or lower than that of AMX.

Table 3.

Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of compounds from plants

| Compound | Original plant | MIC/MBC | Ref. |

| Phenolics/Simple phenols/Polyphenols | |||

| Boropinic acid | Boronia pinnata | MIC: 1.62 μg/mL | Epifano et al[82] |

| Sm. | |||

| Corilagin, 1,2,3,6-tetra-O-galloyl-b-D-glucose | Geranium wilfordii | MIC: 2-8 μg/mL | Zhang et al[83] |

| Egallic acid | Rubus ulmifolius leaves | MIC: 2-10 μg/mL | Martinia et al[66] |

| 3-Farnesyl-2-hydroxybenzoic acid | Piper multiplinervium | MIC: 3.75-12.5 μg/mL | Rüegg et al[84] |

| Epigallocatechin gallate, epicatechin gallate, epigallocatechin, | MIC: 8-256 μg/mL | Mabe et al[85] | |

| epicatechin | |||

| Magnolol | Magnoliae officinalis | MIC: 10-20 μg/mL | Bae et al[86] |

| Psoracorylifols | Psoralea corylifolia | MIC: 12.5-25 μg/mL | Yin et al[87] |

| Resveratrol | Red wine | MIC: 25-100 μg/mL | Paulo et al[88] |

| Cinnamic acid | MIC: 80-200 μg/mL | Bae et al[86] | |

| Allixin | Allium sativum | MIC90: 50 μg/mL | Mahady et al[89] |

| Paeonol, benzoic acid, methyl gallate, | Paeonia lactiflora Roots | MIC: 80-320 μg/mL | Ngan et al[90] |

| 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-galloyl-β-D-glucopyranose | MBC: 320-1280 μg/mL | ||

| Including 3-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-8-prenylchromane-6-propenoic | Brazilian propolis | MIC: 130-1000 μg/mL | Banskota et al[91] |

| acid 10 phenolic acids | |||

| Chlorogenic acid | Anthemis altissima | MIC: 312.5-1250 μg/mL | Konstantinopoulou et al[92] |

| Flavonoids | |||

| Quercetin 3-methyl ether, | Cistus laurifolius leaves | MIC: 3.9-62.5 μg/mL | Ustün et al[93] |

| quercetin 3,7-dimethyl ether, kaempferol 3,7-dimethyl ether | |||

| Kaempferol | Rubus ulmifolius leaves | MBC: 6 μg/mL | Martinia et al[66] |

| Kaempferol 4’-methyl ether, quercetin, rhamnetin, isoquercetrin, | Anthemis altissima | MIC: 6.25-50 μg/mL | Konstantinopoulou et al[92] |

| taxifolin, eriodictyol | |||

| Including licoisoflavone B and licoricidin 16 flavonoids | Licorice | MIC: 6.25-50 μg/mL | Fukai et al[94] |

| Cabreuvin | Myroxylon peruiferum | MIC: 7.8 μg/mL | Ohsaki et al[57] |

| 3,5,7-Trihydroxy-4’-methoxyflavanol, keampferol-3,4’-dimethyl ether | Brazilian propolis | MIC: 500-1000 μg/mL | Banskota et al[91] |

| Quinones | |||

| 2-Methoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone | Impatiens balsamina L. | MIC: 0.156-0.625 μg/mL | Wang et al[95] |

| MBC: 0.313-0.625 μg/mL | |||

| 2-(Hydroxymethyl)anthraquinone, anthraquinone-2-carboxylic acid, | Tabebuia impetiginosa | MIC: 2-8 μg/mL | Park et al[96] |

| Lapachol, plumbagin | Martius ex DC | ||

| Idebenone, duroquinone, menadione, juglone, benzoquinone, | MIC90: 0.8-25 μg/mL | Inatsu et al[97] | |

| coenzyme Q1, coenzyme Q10, decylubiquinone | |||

| Emodin | Rhei Rhizoma | MIC86-99: 250 μg/mL | Wang and Chung[98] |

| Coumarins | |||

| Benzoyl aegelinol, aegelinol | Ferulago campestris (Apiaceae) roots | MIC: 5-25 μg/mL | Basile et al[99] |

| 24 Synthetic coumarin derivatives | MIC: 10-40 μg/mL | Jadhav et al[100] | |

| 23 Synthetic coumarin derivatives | MIC50: 23->100 μg/mL | Kawase et al[101] | |

| Terpenoids | |||

| Arjunglucoside I | Pteleopsis suberosa | MIC: 1.9-7.8 μg/mL | De Leo et al[102] |

| Trichorabdal | Rabdosia trichocarpa | MIC: 2.5-5 μg/mL | Kadota et al[103] |

| Sivasinolide, altissin, 1-epi-tatridin B, desacetyl-β-cyclopyrethrosin, | Anthemis altissima | MIC: 12.5-50 μg/mL | Konstantinopoulou et al[92] |

| tatridin-A | |||

| (Z)-R-santalol (7), (Z)-β-santalol, (Z)-lanceol | Santalum album | MIC: 7.8-31.3 μg/mL | Ochi et al[104] |

| Stigmasta-7,22-diene-3β-ol | Impatiens balsamina L. | MIC: 20-80 μg/mL | Wang et al[95] |

| MBC: 20-80 μg/mL | |||

| Plaunotol | Plau-noi | MIC90: 12.5 mg/mL | Koga et al[105] |

| Terpinen-4-ol | Sclerocarya birrea (Anacardiaceae) | MIC50: 0.004-0.06 μg/mL | Njume et al[106] |

| Alkaloids | |||

| 1-Methyl-2-[(Z)-8-tridecenyl]-4-(1H)-quinolone, | Evodia rutaecarpa fruits | MIC: < 0.05 μg/mL | Hamasaki et al[107] |

| 1-Methyl-2-[(Z)-7-tridecenyl]-4-(1H)-quinolone | |||

| Tryptanthrin | Polygonum tinctorium Lour. | MIC: 2.5 μg/mL | Hashimoto et al[108] |

| Other compounds | |||

| Pyrrolidine | Sclerocarya birrea (Anacardiaceae) | MIC50: 0.05-6.3 μg/mL | Njume et al[106] |

| Diallyl disulfide, diallyl trisulfide, diallyl tetrasulfide, allicin | MIC: 3-100 μg/mL | O’gara et al[109] | |

| MBC: 6-200 μg/mL | |||

| Palmitoyl ascorbate | MIC: 40-400 μg/mL | Tabak et al[110] | |

| Capric acid, lauric acid, myristic acid, myristoleic acid, | MBC: 0.5-5 mmol/L | Sun et al[111] | |

| palmitoleic acid, linolenic acid, monolaurin, monomyristin | |||

MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration; MBC: Minimum bactericidal concentration.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of some anti-Helicobacter pylori compounds from medicinal plants.

Phenolics, simple phenols, and polyphenols: Phenolic compounds are commonly distributed in plants. They are classified as phenolics, simple phenols, and polyphenols. Cinnamic acid and chlorogenic acid are the common representatives of phenolics (Figure 2). Tannin is a group of polymeric phenolic substances, which is divided into two categories based on their chemical nature: hydrolyzable and condensed tannins (Figure 2). As listed on Table 3, boropinic acid (a cinnamic acid derivative from Boronia pinnata Sm.) had the lowest MIC (1.62 μg/mL)[82]; MICs for corilagin (a hydrolyzable tannin from Geranium wilfordii) against 6 H. pylori strains were 2-4 μg/mL[83]; ellagic acid (a hydroxydiphenic acid from Rubus ulmifolius leaves) showed anti-H. pylori activity with 2-10 μg/mL of MICs[66], whereas 3-farnesyl-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (a hydroxybenzoic acid prenylated derivative from Piper multiplinervium) had 3.75-12.5 μg/mL of MICs against 5 H. pylori strains[84].

Flavonoids: Flavonoids are widely distributed throughout the plant kingdom. The family consists of 7 members: flavones, flavanones, flavonols, flavanols, flavan-3-ols (the structural unit of condensed tannins), anthocyanidins, and chalcones with C6-C3-C6 skeleton feature (Figure 2). As indicated in Table 3, the lowest MICs of flavonoids against H. pylori peaked at quercetin 3-methyl ether (isorhamnetin) (MIC: 3.9 μg/mL), a methoxylated flavonol aglycone from Cistus laurifolius leaves[93]; kaempferol, a flavonol from Rubus ulmifolius leaves (MBC: 6 μg/mL)[66]; and cabreuvin, an isoflavone derivative from Myroxylon peruiferum (MIC: 7.8 μg/mL)[57].

Quinones: Quinones are aromatic rings with two ketone substitutions (Figure 2). These compounds, largely responsible for flower color, are ubiquitous in nature and highly reactive. In Table 3, MeONQ (a naphthoquinone isolated from I. balsamina L.) has the strongest anti-H. pylori action of those quinones with 0.156-0.625 μg/mL of MICs and 0.313-0.625 μg/mL of MBCs against multiple-antibiotic (CLR, MTZ, and LVX) resistant H. pylori strains. The activity was equivalent to that of AMX as well as not being influenced by pH (4-8) or heat (121 °C for 15 min) treatments. Interestingly, MeONQ abounds in the I. balsamina L. pod at the level of 4.39% (w/w)[95]. Subsequently, 2-(hydroxymethyl)anthraquinone followed, which is an anthraquinone isolated from Tabebuia impetiginosa Martius ex DC (Taheebo) with 2 μg/mL of MIC[96].

Coumarins: The chemical structure of coumarins are benzene fused with an α-pyrone ring (Figure 2), which are responsible for the characteristic odor of hay[112]. Coumarins are widely found in plants. Basile et al[99] reported that aegelinol and its derivative [benzoyl aegelinol isolated from Ferulago campestris (Apiaceae) roots] showed anti-H. pylori activity with 5-25 μg/mL of MIC. In fact, many coumarin derivatives are synthetic and are commercially sold as supplementary diet products. Jadhav et al[100] and Kawase et al[101] studied the anti-H. pylori activity of 23 and 24 synthetic coumarin derivatives, respectively, wherein they found those coumarin derivatives to have anti-inhibitory activity, but not particularly high (MIC: 10 to > 100 μg/mL).

Terpenoids: Terpenoids derived from terpenes containing oxygen in molecule. Isoprene is the basic structural unit of terpenes. Monoterpenes (C10H16), diterpenes (C20), triterpenes (C30), and tetraterpenes (C40) commonly occur in nature (Figure 2). Arjunglucoside I is an oleanane saponine isolated from Pteleopsis suberosa Engl. Et Diels stem bark (Combretaceae), which possesses anti-H. pylori activity (MIC: 1.9-7.8 μg/mL) against vacA/cagA positive and metronidazole-resistant strains[102]. Trichorabdal A (a diterpene from Rabdosia trichocarpa) showed strong anti-H. pylori activity with 2-5 μg/mL of MICs[103]. A remarkable anti-H. pylori compound, terpinen-4-ol, was isolated from Sclerocarya birrea (Anacardiaceae) with 0.004-0.06 μg/mL of MIC50, being similar to that of AMX (MIC50: 0.0003-0.06 μg/mL)[106].

Alkaloids: Heterocyclic nitrogen compounds are called alkaloids (Figure 2). The first pharmaceutically used alkaloid was porphine from the opium poppy Papaver somniferum[112]. 1-Methyl-2-[(Z)-8-tridecenyl]-4-(1H)-quinolone and 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-7-tridecenyl]-4-(1H)-quinolone were isolated from Evodia rutaecarpa fruits traditionally used in Chinese medicine. Both alkaloids were found to have the relatively low MIC against H. pylori (< 0.05 μg/mL), which was similar to AMX and CLR[107].

Mechanisms of anti-H. pylori action

As aforementioned, numerous studies have reported natural products’ anti-H. pylori activity. However, only a few papers have concerned the action mechanisms. Within this literature, the mechanisms include urease activity inhibition, anti-adhesion activity, DNA damage, protein synthesis inhibition, and oxidative stress, which are each addressed below.

Urease activity inhibition: Both Acacia nilotica and Calotropis procera extracts possessed anti-H. pylori activity possibly due to inhibition of urease activity through competitive and mixed type mechanisms, respectively, in which both Vmax and affinity (Km) were changed for the latter type[61]. The anti-H. pylori actions of 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-β-D-glucopyranose from Paeonia lactiflora roots were considered to work in multiple manners. The hydrophobicity of the compound facilitates it to bind to cell membranes resulting in the loss of membrane integrity as well as inhibition of urease activity and UreB (an adhesin) expression[90]. The inhibitory effect of resveratrol against H. pylori was possibly due to inhibition of urease activity[88]. The action mode of mixed oregano and cranberry water-soluble extract (a commercial product) may be through urease activity inhibition and disruption of energy production by inhibition of proline dehydrogenase at the plasma membrane[113]. In an in vivo study, both the dichloromethane fraction and the ethanolic extract of Calophyllum brasiliense stem bark decreased the number of urease-positive Wistar rats, which was confirmed by the reduction of H. pylori presence in histopathological analysis[114].

Anti-adhesion activity: The turmeric, borage, and fresh parsley water extracts were found to inhibit adhesion of H. pylori 11637 to the human stomach section; moreover, 33.9%-61.9% of inhibition rates for antigens Lewis a and Lewis b were observed[115]. The Glycyrrhiza glabra root aqueous extract and polysaccharides exhibited strong anti-adhesive activity under a fluroscent microscopy of human gastric mucosa aliquots with fluorescent-labeled H. pylori[116]. EPs 7630, a commercial product of the Pelargonium sidoides DC (Geraniaceae) root extract, showed good anti-adhesive activity in a dose-dependent manner (0.001-10 mg/mL)[117]. Plaunotol, an acyclic diterpene alcohol isolated from the leaves of the plau-noi tree in Thailand, was found to suppress adhesion of H. pylori to adenocarcinoma cells as well as inhibit IL-8 secretion in a dose-dependent manner[118].

Oxidative stress: MeONQ exhibited very strong bactericidal H. pylori activity[95]. The possible mechanisms of MeONQ are due to the high redox potential of the compound. When MeONQ enters the cell membrane, it is immediately metabolized by flavoenzymes and undergoes serial redox cyclic reactions to produce a high amount of ROS (O-•, MeONQ-•, and H2O2). Those ROS further damage cellular macromolecules and may lead to H. pylori death[95].

Amphiphilic nature of compounds: Anti-H. pylori compound terpinen-4-ol from Sclerocarya birrea (Anacardiaceae) is a monocyclic monoterpene derivative with amphiphilic nature. The strong anti-H. pylori activity of the compound was thought to be a result of its hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity. The hydrophilicity allows this compound to diffuse through surrounding water to the bacterial cell wall, whereas the hydrophobicity lets this compound close in on and partially bind to the cytoplasmic membrane resulting in the loss of membrane integrity[107].

Others: Glabridin (a major flavonoid of GutGards®) exhibited anti-H. pylori activity. Additionally, GutGard® showed a potent inhibitory effect on DNA gyrase and dihydrofolate reductase with 4.40 and 3.33 mg/mL of IC50, respectively[119]. Emodin (1,3,8-trihydroxy-6-methylanthraquinone), a major bioactive compound of Radix et Rhizoma Rhei (a Chinese herb medicine), induced H. pylori DNA damage[98]. Flavonoids vitexin, isovitexin, rhamnopyranosylvitexin, and isoembigenin from Piper carpunya Ruiz & Pav. showed anti-H. pylori activity. Those compounds effectively released myeloperoxidase from rat peritoneal leukocytes as well as inhibited of H+,K+-ATPase activity[120]. N-Acetylation, a major metabolic pathway for arylamine carcinogens, is catalysed by cytosolic arylamine N-acetyltransferase. Rhein, one of the bioactive component of Dahuang, effectively inhibited N-acetyltransferase activity and H. pylori growth[121].

ANTI-H. PYLORI-INDUCED GASTRIC INFLAMMATION OF PLANT PRODUCTS

Once H. pylori attaches to host cells, the signal transduction is immediately initiated, and then transcription/translation of the relevant inflammatory proteins, especially for IL-8, IL-6, INF-γ, TNF-α, COX-2, and ICAM-1, through NF-κB, MAPK, MEK/ERK, SHP-2/ERK, and Nox-1 pathways (Figure 1). Those proteins can further induce immune response cascades resulting in severe H. pylori-infected gastric mucosa inflammation. As proposed in the Correa pathway[22], the H. pylori-induced gastric chronic inflammation can progress to superficial gastritis, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and finally adenocarcinoma. Specifically, atrophic gastritis is a critical initiating step in the progression toward gastric cancer[22-24]. There have been many studies focusing on anti-H. pylori-induced inflammation and the relevant mechanisms, in which NF-κB and MAPK pathways were the most discussed.

Inhibition of NF-κB pathway

The H. pylori-induced NF-κB pathway is presented in Figure 1B. Many natural products were found to have anti-H. pylori induced inflammation activity through the suppression of NF-κB activation. Apigenin, one of the most common flavonoids, is widely distributed in fruits and vegetables, especially abound in parsley and celery. Apigenin treatments (9.3-74 μmol/L) significantly inhibited NF-κB activation, thus, the IκBα expression increased and inflammatory factor (COX-2, ICAM-1, ROS, IL-6, and IL-8) expressions decreased. Specifically, the ROS levels decreased partially based on the intrinsic scavenging property of apigenin[122]. Curcumin, a natural polyphenol, presents in turmeric. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) is a downstream member of NF-κB regulated by NF-κB. Curcumin significantly suppressed NF-κB activation as well as IKK activation and IκBα degradation; and therefore inhibited AID activity in the H. pylori-infected adenocarcinoma cells[123]. Capsaicin, a terpenoid, is an active compound of chilies and chili peppers. The compound significantly inhibited H. pylori-induced IL-8 production through inhibition of IKK and NF-κB activation in a dose- and time-dependent manner[124]. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE), an active compound of propolis, has been reported to have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties. CAPE inhibited H. pylori-induced NF-κB and AP-1 DNA binding activity in a dose- and time-dependent manner in H. pylori-infected AGS cells. The suppression of NF-κB (Figure 1B) and MAPK (Figure 1C) pathway activation was involved, and thus TNF-α, IL-8, and COX-2 expressions decreased. Additionally, CAPE also suppressed H. pylori-induced cell proliferation[125]. San-Huang-Xie-Xin-Tang (SHXT), a traditional oriental medicinal formula containing Rhizoma Coptidis (Coptis chinesis Franch), Scutellariae radix (Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi), and Rhei rhizome (Rheum officinale Baill), has been used to treat gastritis, gastric bleeding, and peptic ulcers. SHXT and baicalin (an active compound of SHXT) was found to decrease IκBα phosphorylation and inflammatory factor (IL-8, COX-2, and iNOS) expressions in H. pylori-infected AGS cells, of which the transduction factor NF-κB activation was inhibited. SHXT and baicalin might exert anti-inflammatory and gastroprotective effects in H. pylori-induced gastric inflammation[126]. Zaidi et al[127] examined the anti-inflammatory effects of selected Pakistani medicinal plants and found that 12 plants (including Alpinia galangal) exhibited strong inhibitory activity against IL-8 secretion in H. pylori-infected AGS cells at 100 μg/mL of 70% ethanol extracts. Moreover, significant ROS suppression was demonstrated in the 6 included Achillea millefolium extracts. Notably, an in vivo study of anti-inflammatory effects of CAPE was reported by Toyoda et al[128]. CAPE has inhibitory effects on H. pylori-induced gastritis in Mongolian gerbils through the suppression of NF-κB activation in which TNF-α, INF-γ, IL-2, IL-8, KC (IL-8 homologue), and iNOS expressions significantly decreased.

With exception to H. pylori-induced cell inflammation, paeoniflorin (a benzoic acid derivative from Paeonia lactiflora pall roots) exhibited dramatic inhibition of NF-κB activation in a time- and dose-dependent manner in human gastric carcinoma cells (SGC-7901). Moreover, the compound enhanced 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis of the gastric carcinoma cells[129].

Inhibition of MAPK pathway

β-Carotene is a well-known carotenoid and 10-20 μmol/L treatment doses significantly decreased p-38, JNK, ERK1/2 phosphorylation as well as decreased DNA binding activity of NF-κB and AP-1 in H. pylori-infected AGS cells in a dose-dependent manner. The ROS level, iNOS and COX-2 expressions also decreased. Both NF-κB (Figure 1B) and MAPK (Figure 1C) pathway activation were inhibited by β-carotene[130]. As aforementioned, curcumin significantly inhibited NF-κB activation[123]. Foryst-Ludwig et al[131] reported that curcumin inhibited IκBα degradation, IKKα/β activity, and NF-κB DNA-binding activity in H. pylori-infected AGS cells. Additionally, JNK1/2, ERK1/2, and p38 phosphorylation were also remarkably suppressed by the compound. The suppressions of both NF-κB (Figure 1B) and MAPK (Figure 1C) pathway activation were demonstrated in curcumin.

IN VIVO STUDIES

There have been a few studies to discuss anti-H. pylori and anti-H. pylori induced gastric inflammation (or gastritis) activities of natural products in animals. As aforementioned[85], tea catechins had anti-H. pylori activity (MIC: 8-256 μg/mL) in vitro. The product was given in diet (0.5%) for 2 wk to Mongolian gerbils. The H. pylori colonization reduced by 10%-36% and gastric mucosal injury significantly decreased[85]. Both kaempferol and tryptanthrin showed anti-H. pylori activity[66,109]. A mixture of kaempferol and tryptanthrin at 5.0 mg/bw of treatment dose was orally administered to Mongolian gerbils twice a day for 10 d. The viable counts of H. pylori in the stomach significantly decreased[132]. Quercetin, a flavonoid, is widely present in fruits and vegetables. H. pylori-infected guinea pigs were orally given quercetin at 200 mg/kgbw per day, which significantly decreased neutrophil leukocyte infiltration, H. pylori colonization, and lipid peroxide concentration in the pyloric antrum[133]. The carotenoid-rich acetone extract of Chlorococcum sp. (a microalgae) was orally given to H. pylori-infected BALB/c mice at 100 mg/kgbw per day. The algae meal significantly decreased H. pylori density in the stomach and INF-γ and IL-4 levels in splenocytes; the H. pylori-induced inflammation in BALB/c mice was effectively inhibited[134]. A green tea product containing 30.7% epigallocatechin gallate, 17.0% epigallocatechin, 6.4% epicatechin gallate, 5.7% gallocatechin, 4.2% gallocatechin gallate, 4.1% epicatechin, and 1.1% catechin was given in drinking water at 500-2000 ppm doses for 6 wk to H. pylori-infected Mongolian gerbils. Gastritis and the prevalence of H. pylori in the Mongolian gerbils were significantly suppressed in a dose-dependent manner[135]. Additionally, a garlic ethanol aqueous extract was given at 1%-4% of dosages in a diet to H. pylori-infected Mongolian gerbils. The garlic extract significantly decreased hemorrhagic spots in the glandular stomach and gastritis scores as well as decreased stomach weight, which might be useful as an agent for prevention of H. pylori-induced gastritis[136]. In a 4-wk short-term H. pylori infection model, H. pylori-infected C57BL6/J mice were orally administered apple peel polyphenol (150 and 300 mg/kgbw per day). The treatment significantly decreased H. pylori colonization, gastritis scores, and malondialdehyde levels in the animals[137]. The Thai medicines finger-root and turmeric rhizome with 95% ethanol extracts were given to H. pylori-infected Mongolian gerbils in a basal diet at 100 mg/kgbw per day. The finger-root extract effectively decreased mucosal/submucosal chronic and acute inflammation scores for those Mongolian gerbils. The turmeric extract only reduced chronic inflammation scores, without anti-acute inflammation effects[138]. In 32-wk and 52-wk animal tests, apigenin treatments (30-60 mg/kgbw per day) effectively decreased H. pylori colonization, atrophic gastritis, and dysplasia/gastric cancer rates in H. pylori-infected Mongolian gerbils. Apigenin has the remarkable ability to inhibit H. pylori-induced gastric cancer progression as well as possessing potent anti-gastric cancer activity[139].

CONCLUSION

H. pylori infection may result in severe gastric inflammation and gastric cancer. CagA is a key virulent factor, which initiates host cells’ NF-κB, MAPK, and SHP-2/ERK pathways to transcribe and translate inflammatory factors (COX-2, ICAM-1, iNOS, ROS) and proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, INF-γ, TNF-α). Overproduction of those substances cause extensive infected-site inflammation and then progress to superficial gastritis, atrophic gastritis, and finally gastric cancer.

Numerous medicinal plant products including plant extracts, partial purified fractions, and isolated compounds were reported for their anti-H. pylori activity. A few of them exhibited strong anti-H. pylori activity, being almost equal to clinical antibiotics. In animals, few plant products had anti-H. pylori effects which effectively decreased H. pylori colonization in the stomach. H. pylori-induced atrophic gastritis is a critical point to progress to gastric cancer. Some plant products, including isolated compounds and plant formulas, significantly decreased such gastric inflammation and injury, and even inhibited gastric cancer progression.

H. pylori eradication with antibiotic regimens has a limitation mostly due to antibiotic resistance. Medicinal plant compounds and other natural products provide another choice or opportunity to eradicate H. pylori infection. Medicinal plant compounds may also provide effective way to reduce H. pylori-induced gastric inflammation and even gastric cancer. However, potential cytotoxicity and adverse side effects might present from those medicinal plant products. Further relevant cytotoxicity studies both in vitro and in vivo will be required. Further evaluation of pharmacokin-etics for those products in animals will be also required.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Balaban YH, Kanizaj TF, Zhu YL S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Warren JR, Marshall BJ. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1983;1:1273–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor D, Parsonneet , J . Infections of the gastrointestinal tract. In: Infection of the gastrointestinal tract., editor. New York: Ravan Press; 1995. pp. 551–563. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, Vol 61. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994. pp. 177–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Covacci A, Telford JL, Del Giudice G, Parsonnet J, Rappuoli R. Helicobacter pylori virulence and genetic geography. Science. 1999;284:1328–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dundon WG, de Bernard M, Montecucco C. Virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori. Int J Med Microbiol. 2001;290:647–658. doi: 10.1016/s1438-4221(01)80002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mobley HLT, Mendz GL, Hazell SL. Helicobacter pylori. Washington (DC): ASM Press; 2001. pp. Pp. 471–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaoka Y. Mechanisms of disease: Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:629–641. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aguilar GR, Ayala G, Fierros-Zárate G. Helicobacter pylori: recent advances in the study of its pathogenicity and prevention. Salud Publica Mex. 2001;43:237–247. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342001000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atherton JC. H. pylori virulence factors. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:105–120. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanke SR. Micro-managing the executioner: pathogen targeting of mitochondria. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boquet P, Ricci V. Intoxication strategy of Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polk DB, Peek RM. Helicobacter pylori: gastric cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:403–414. doi: 10.1038/nrc2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wada A, Yamasaki E, Hirayama T. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin, VacA, is responsible for gastric ulceration. J Biochem. 2004;136:741–746. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim IJ, Blanke SR. Remodeling the host environment: modulation of the gastric epithelium by the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA) Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:37. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palframan SL, Kwok T, Gabriel K. Vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), a key toxin for Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:92. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuck D, Kolmerer B, Iking-Konert C, Krammer PH, Stremmel W, Rudi J. Vacuolating cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori induces apoptosis in the human gastric epithelial cell line AGS. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5080–5087. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.5080-5087.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cover TL, Krishna US, Israel DA, Peek RM. Induction of gastric epithelial cell apoptosis by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. Cancer Res. 2003;63:951–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mimuro H, Suzuki T, Nagai S, Rieder G, Suzuki M, Nagai T, Fujita Y, Nagamatsu K, Ishijima N, Koyasu S, et al. Helicobacter pylori dampens gut epithelial self-renewal by inhibiting apoptosis, a bacterial strategy to enhance colonization of the stomach. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:250–263. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones KR, Whitmire JM, Merrell DS. A tale of two toxins: Helicobacter pylori CagA and VacA modulate host pathways that impact disease. Front Microbiol. 2010;1:115. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2010.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu J, Xu S, Zhu Y. Helicobacter pylori CagA: a critical destroyer of the gastric epithelial barrier. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1830–1837. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2589-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatakeyama M, Higashi H. Helicobacter pylori CagA: a new paradigm for bacterial carcinogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:835–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735–6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox JG, Wang TC. Helicobacter pylori--not a good bug after all. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:829–832. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200109133451111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox JG, Wang TC. Inflammation, atrophy, and gastric cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:60–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI30111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jobin C, Sartor RB. The I kappa B/NF-kappa B system: a key determinant of mucosalinflammation and protection. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C451–C462. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.3.C451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs MD, Harrison SC. Structure of an IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complex. Cell. 1998;95:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naito Y, Yoshikawa T. Molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation and oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:323–336. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00868-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crantree JE, Naumann M. Epithelial cell signaling in Helicobacter pylori infection. Curr Signal Transduct Ther. 2006;1:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peek RM, Fiske C, Wilson KT. Role of innate immunity in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric malignancy. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:831–858. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonizzi G, Karin M. The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JS, Paek NS, Kwon OS, Hahm KB. Anti-inflammatory actions of probiotics through activating suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) expression and signaling in Helicobacter pylori infection: a novel mechanism. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:194–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allison CC, Kufer TA, Kremmer E, Kaparakis M, Ferrero RL. Helicobacter pylori induces MAPK phosphorylation and AP-1 activation via a NOD1-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2009;183:8099–8109. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montecucco C, Rappuoli R. Living dangerously: how Helicobacter pylori survives in the human stomach. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:457–466. doi: 10.1038/35073084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho SO, Lim JW, Kim KH, Kim H. Involvement of Ras and AP-1 in Helicobacter pylori-induced expression of COX-2 and iNOS in gastric epithelial AGS cells. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:988–996. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0828-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambeth JD. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:181–189. doi: 10.1038/nri1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teshima S, Rokutan K, Nikawa T, Kishi K. Guinea pig gastric mucosal cells produce abundant superoxide anion through an NADPH oxidase-like system. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1186–1196. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teshima S, Kutsumi H, Kawahara T, Kishi K, Rokutan K. Regulation of growth and apoptosis of cultured guinea pig gastric mucosal cells by mitogenic oxidase 1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G1169–G1176. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.6.G1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Babior BM, Lambeth JD, Nauseef W. The neutrophil NADPH oxidase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;397:342–344. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morena M, Cristol JP, Senécal L, Leray-Moragues H, Krieter D, Canaud B. Oxidative stress in hemodialysis patients: is NADPH oxidase complex the culprit? Kidney Int Suppl. 2002;(80):109–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.61.s80.20.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kroemer G, Dallaporta B, Resche-Rigon M. The mitochondrial death/life regulator in apoptosis and necrosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:619–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fera MT, Giannone M, Pallio S, Tortora A, Blandino G, Carbone M. Antimicrobial activity and postantibiotic effect of flurithromycin against Helicobacter pylori strains. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17:151–154. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boyanova L. Comparative evaluation of two methods for testing metronidazole susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori in routine practice. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;35:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(99)00039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park JB, Imamura L, Kobashi K. Kinetic studies of Helicobacter pylori urease inhibition by a novel proton pump inhibitor, rabeprazole. Biol Pharm Bull. 1996;19:182–187. doi: 10.1248/bpb.19.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuchiya M, Imamura L, Park JB, Kobashi K. Helicobacter pylori urease inhibition by rabeprazole, a proton pump inhibitor. Biol Pharm Bull. 1995;18:1053–1056. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Susan M, Mou MD. The relationship between Helicobacter infection and peptic ulcer disease. Prim Care Update Ob/Gyns. 1998;5:229–232. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sorba G, Bertinaria M, Di Stilo A, Gasco A, Scaltrito MM, Brenciaglia MI, Dubini F. Anti-Helicobacter pylori agents endowed with H2-antagonist properties. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:403–406. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00671-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Midolo PD, Norton A, von Itzstein M, Lambert JR. Novel bismuth compounds have in vitro activity against Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:229–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Worrel JA, Stoner SC. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Med Update Psychiat. 1998;4:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferrero M, Ducóns JA, Sicilia B, Santolaria S, Sierra E, Gomollón F. Factors affecting the variation in antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori over a 3-year period. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;16:245–248. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glupczynski Y, Mégraud F, Lopez-Brea M, Andersen LP. European multicentre survey of in vitro antimicrobial resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:820–823. doi: 10.1007/s100960100611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirschl A, Andersen LP, Glupczynski Y. Surveillance of Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Europe 2008-2009. Gastroenterology. 2009;140:S312. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang YC, Wu DC, Liao JJ, Wu CH, Li WY, Weng BC. In vitro activity of Impatiens balsamina L. against multiple antibiotic-resistant Helicobacter pylori. Am J Chin Med. 2009;37:713–722. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X09007181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Castillo-Juárez I, González V, Jaime-Aguilar H, Martínez G, Linares E, Bye R, Romero I. Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of plants used in Mexican traditional medicine for gastrointestinal disorders. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122:402–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mahady GB, Pendland SL, Stoia A, Chadwick LR. In vitro susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori to isoquinoline alkaloids from Sanguinaria canadensis and Hydrastis canadensis. Phytother Res. 2003;17:217–221. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zaidi SF, Yamada K, Kadowaki M, Usmanghani K, Sugiyama T. Bactericidal activity of medicinal plants, employed for the treatment of gastrointestinal ailments, against Helicobacter pylori. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;121:286–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Y, Xu C, Zhang Q, Liu JY, Tan RX. In vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori action of 30 Chinese herbal medicines used to treat ulcer diseases. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;98:329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ohsaki A, Takashima J, Chiba N, Kawamura M. Microanalysis of a selective potent anti-Helicobacter pylori compound in a Brazilian medicinal plant, Myroxylon peruiferum and the activity of analogues. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:1109–1112. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gadhi CA, Benharref A, Jana M, Lozniewski A. Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of Aristolochia paucinervis Pomel extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;75:203–205. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yeşilada E, Gürbüz I, Shibata H. Screening of Turkish anti-ulcerogenic folk remedies for anti-Helicobacter pylori activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;66:289–293. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stege PW, Davicino RC, Vega AE, Casali YA, Correa S, Micalizzi B. Antimicrobial activity of aqueous extracts of Larrea divaricata Cav (jarilla) against Helicobacter pylori. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:724–727. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Amin M, Anwar F, Naz F, Mehmood T, Saari N. Anti-Helicobacter pylori and urease inhibition activities of some traditional medicinal plants. Molecules. 2013;18:2135–2149. doi: 10.3390/molecules18022135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nostro A, Cellini L, Di Bartolomeo S, Cannatelli MA, Di Campli E, Procopio F, Grande R, Marzio L, Alonzo V. Effects of combining extracts (from propolis or Zingiber officinale) with clarithromycin on Helicobacter pylori. Phytother Res. 2006;20:187–190. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chinniah A, Mohapatra S, Goswami S, Mahapatra A, Kar SK, Mallavadhani UV, Das PK. On the potential of Tephrosia purpurea as anti-Helicobacter pylori agent. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124:642–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Silva O, Viegas S, de Mello-Sampayo C, Costa MJ, Serrano R, Cabrita J, Gomes ET. Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of Terminalia macroptera root. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:872–876. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Malekzadeh F, Ehsanifar H, Shahamat M, Levin M, Colwell RR. Antibacterial activity of black myrobalan (Terminalia chebula Retz) against Helicobacter pylori. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;18:85–88. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00352-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martini S, D’Addario C, Colacevich A, Focardi S, Borghini F, Santucci A, Figura N, Rossi C. Antimicrobial activity against Helicobacter pylori strains and antioxidant properties of blackberry leaves (Rubus ulmifolius) and isolated compounds. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Castillo-Juárez I, Rivero-Cruz F, Celis H, Romero I. Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of anacardic acids from Amphipterygium adstringens. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;114:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ndip RN, Ajonglefac AN, Mbullah SM, Tanih NF, Akoachere JTK, Ndip LM, Luma HN, Wirmum C, Ngwa F, Efange SMN. In vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of Lycopodium cernuum (Linn) Pic. Serm. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008;7:3989–3994. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ndip RN, Malange Tarkang AE, Mbullah SM, Luma HN, Malongue A, Ndip LM, Nyongbela K, Wirmum C, Efange SM. In vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of extracts of selected medicinal plants from North West Cameroon. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;114:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Njume C, Afolayan AJ, Ndip RN. Preliminary phytochemical screening and in vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of acetone and aqueous extracts of the stem bark of Sclerocarya birrea (Anacardiaceae) Arch Med Res. 2011;42:252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Germanò MP, Sanogo R, Guglielmo M, De Pasquale R, Crisafi G, Bisignano G. Effects of Pteleopsis suberosa extracts on experimental gastric ulcers and Helicobacter pylori growth. J Ethnopharmacol. 1998;59:167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(97)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nostro A, Cellini L, Di Bartolomeo S, Di Campli E, Grande R, Cannatelli MA, Marzio L, Alonzo V. Antibacterial effect of plant extracts against Helicobacter pylori. Phytother Res. 2005;19:198–202. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cellini L, Di Campli E, Masulli M, Di Bartolomeo S, Allocati N. Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori by garlic extract (Allium sativum) FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1996;13:273–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cwikla C, Schmidt K, Matthias A, Bone KM, Lehmann R, Tiralongo E. Investigations into the antibacterial activities of phytotherapeutics against Helicobacter pylori and Campylobacter jejuni. Phytother Res. 2010;24:649–656. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cogo LL, Monteiro CL, Miguel MD, Miguel OG, Cunico MM, Ribeiro ML, de Camargo ER, Kussen GM, Nogueira Kda S, Costa LM. Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of plant extracts traditionally used for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. Braz J Microbiol. 2010;41:304–309. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822010000200007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adeniyi BA, Anyiam FM. In vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori potential of methanol extract of Allium ascalonicum Linn. (Liliaceae) leaf: susceptibility and effect on urease activity. Phytother Res. 2004;18:358–361. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Voravuthikunchai SP, Mitchell H. Inhibitory and killing activities of medicinal plants against multiple antibiotic-resistant Helicobacter pylori. J Health Sci. 2008;54:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stamatis G, Kyriazopoulos P, Golegou S, Basayiannis A, Skaltsas S, Skaltsa H. In vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of Greek herbal medicines. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;88:175–179. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang YC, Huang TL. Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of Plumbago zeylanica L. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2005;43:407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang YC, Huang TL. Screening of anti-Helicobacter pylori herbs deriving from Taiwanese folk medicinal plants. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2005;43:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ohno T, Kita M, Yamaoka Y, Imamura S, Yamamoto T, Mitsufuji S, Kodama T, Kashima K, Imanishi J. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils against Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2003;8:207–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Epifano F, Menghini L, Pagiotti R, Angelini P, Genovese S, Curini M. In vitro inhibitory activity of boropinic acid against Helicobacter pylori. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:5523–5525. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang XQ, Gu HM, Li XZ, Xu ZN, Chen YS, Li Y. Anti-Helicobacter pylori compounds from the ethanol extracts of Geranium wilfordii. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;147:204–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rüegg T, Calderón AI, Queiroz EF, Solís PN, Marston A, Rivas F, Ortega-Barría E, Hostettmann K, Gupta MP. 3-Farnesyl-2-hydroxybenzoic acid is a new anti-Helicobacter pylori compound from Piper multiplinervium. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;103:461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mabe K, Yamada M, Oguni I, Takahashi T. In vitro and in vivo activities of tea catechins against Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1788–1791. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bae EA, Han MJ, Kim NJ, Kim DH. Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of herbal medicines. Biol Pharm Bull. 1998;21:990–992. doi: 10.1248/bpb.21.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yin S, Fan CQ, Yue JM. Psoracorylifols A-E, five novel compounds with activity against Helicobacter pylori from seeds of Psoralea corylofolia. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:2569–2575. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Paulo L, Oleastro M, Gallardo E, Queiroz JA, Domingues F. Anti-Helicobacter pylori and urease inhibitory activities of resveratrol and red wine. Food Res Intl. 2011;44:964–969. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mahady GB, Matsuura H, Pendland SL. Allixin, a phytoalexin from garlic, inhibits the growth of Helicobacter pylori in vitro. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3454–3455. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ngan LT, Moon JK, Shibamoto T, Ahn YJ. Growth-inhibiting, bactericidal, and urease inhibitory effects of Paeonia lactiflora root constituents and related compounds on antibiotic-susceptible and -resistant strains of Helicobacter pylori. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:9062–9073. doi: 10.1021/jf3035034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Banskota AH, Tezuka Y, Adnyana IK, Ishii E, Midorikawa K, Matsushige K, Kadota S. Hepatoprotective and anti-Helicobacter pylori activities of constituents from Brazilian propolis. Phytomedicine. 2001;8:16–23. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Konstantinopoulou M, Karioti A, Skaltsas S, Skaltsa H. Sesquiterpene lactones from Anthemis altissima and their anti-Helicobacter pylori activity. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:699–702. doi: 10.1021/np020472m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ustün O, Ozçelik B, Akyön Y, Abbasoglu U, Yesilada E. Flavonoids with anti-Helicobacter pylori activity from Cistus laurifolius leaves. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;108:457–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fukai T, Marumo A, Kaitou K, Kanda T, Terada S, Nomura T. Anti-Helicobacter pylori flavonoids from licorice extract. Life Sci. 2002;71:1449–1463. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01864-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang YC, Li WY, Wu DC, Wang JJ, Wu CH, Liao JJ, Lin CK. In vitro activity of 2-methoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone and stigmasta-7,22-diene-3β-ol from impatiens balsamina L. against multiple antibiotic-resistant Helicobacter pylori. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:704721. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Park BS, Lee HK, Lee SE, Piao XL, Takeoka GR, Wong RY, Ahn YJ, Kim JH. Antibacterial activity of Tabebuia impetiginosa Martius ex DC (Taheebo) against Helicobacter pylori. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;105:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Inatsu S, Ohsaki A, Nagata K. Idebenone acts against growth of Helicobacter pylori by inhibiting its respiration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2237–2239. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01118-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang HH, Chung JG. Emodin-induced inhibition of growth and DNA damage in the Helicobacter pylori. Curr Microbiol. 1997;35:262–266. doi: 10.1007/s002849900250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Basile A, Sorbo S, Spadaro V, Bruno M, Maggio A, Faraone N, Rosselli S. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of coumarins from the roots of Ferulago campestris (Apiaceae) Molecules. 2009;14:939–952. doi: 10.3390/molecules14030939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jadhav SG, Meshram RJ, Gond DS, Gacche RN. Inhibition of growth of Helicobacter pylori and its urease by coumarin derivatives: Molecular docking analysis. J Pharmacy Res. 2013;7:705–711. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kawase M, Tanaka T, Sohara Y, Tani S, Sakagami H, Hauer H, Chatterjee SS. Structural requirements of hydroxylated coumarins for in vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity. In Vivo. 2003;17:509–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.De Leo M, De Tommasi N, Sanogo R, D’Angelo V, Germanò MP, Bisignano G, Braca A. Triterpenoid saponins from Pteleopsis suberosa stem bark. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:2623–2629. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kadota S, Basnet P, Ishii E, Tamura T, Namba T. Antibacterial activity of trichorabdal A from Rabdosia trichocarpa against Helicobacter pylori. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1997;286:63–67. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(97)80076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ochi T, Shibata H, Higuti T, Kodama KH, Kusumi T, Takaishi Y. Anti-Helicobacter pylori compounds from Santalum album. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:819–824. doi: 10.1021/np040188q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Koga T, Kawada H, Utsui Y, Domon H, Ishii C, Yasuda H. In-vitro and in-vivo antibacterial activity of plaunotol, a cytoprotective antiulcer agent, against Helicobacter pylori. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:919–929. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.5.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Njume C, Afolayan AJ, Green E, Ndip RN. Volatile compounds in the stem bark of Sclerocarya birrea (Anacardiaceae) possess antimicrobial activity against drug-resistant strains of Helicobacter pylori. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hamasaki N, Ishii E, Tominaga K, Tezuka Y, Nagaoka T, Kadota S, Kuroki T, Yano I. Highly selective antibacterial activity of novel alkyl quinolone alkaloids from a Chinese herbal medicine, Gosyuyu (Wu-Chu-Yu), against Helicobacter pylori in vitro. Microbiol Immunol. 2000;44:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hashimoto T, Agr H, Chaen H, Fukuda S, Kurimoto M. Isolation and identification of anti-Helicobacter pylori compounds from Polygonum tinctorium Lour. Nat Med. 1999;53:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 109.O'Gara EA, Hill DJ, Maslin DJ. Activities of garlic oil, garlic powder, and their diallyl constituents against Helicobacter pylori. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2269–2273. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.5.2269-2273.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tabak M, Armon R, Rosenblat G, Stermer E, Neeman I. Diverse effects of ascorbic acid and palmitoyl ascorbate on Helicobacter pylori survival and growth. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;224:247–253. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sun CQ, O’Connor CJ, Roberton AM. Antibacterial actions of fatty acids and monoglycerides against Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;36:9–17. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cowan MM. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:564–582. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lin YT, Kwon YI, Labbe RG, Shetty K. Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori and associated urease by oregano and cranberry phytochemical synergies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8558–8564. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8558-8564.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Souza Mdo C, Beserra AM, Martins DC, Real VV, Santos RA, Rao VS, Silva RM, Martins DT. In vitro and in vivo anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of Calophyllum brasiliense Camb. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;123:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.O'Mahony R, Al-Khtheeri H, Weerasekera D, Fernando N, Vaira D, Holton J, Basset C. Bactericidal and anti-adhesive properties of culinary and medicinal plants against Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7499–7507. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i47.7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wittschier N, Faller G, Hensel A. Aqueous extracts and polysaccharides from liquorice roots (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) inhibit adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric mucosa. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;125:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wittschier N, Faller G, Hensel A. An extract of Pelargonium sidoides (EPs 7630) inhibits in situ adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human stomach. Phytomedicine. 2007;14:285–288. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Takagi A, Koga Y, Aiba Y, Kabir AM, Watanabe S, Ohta-Tada U, Osaki T, Kamiya S, Miwa T. Plaunotol suppresses interleukin-8 secretion induced by Helicobacter pylori: therapeutic effect of plaunotol on H. pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:374–380. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Asha MK, Debraj D, Prashanth D, Edwin JR, Srikanth HS, Muruganantham N, Dethe SM, Anirban B, Jaya B, Deepak M, et al. In vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of a flavonoid rich extract of Glycyrrhiza glabra and its probable mechanisms of action. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;145:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Quílez A, Berenguer B, Gilardoni G, Souccar C, de Mendonça S, Oliveira LF, Martín-Calero MJ, Vidari G. Anti-secretory, anti-inflammatory and anti-Helicobacter pylori activities of several fractions isolated from Piper carpunya Ruiz & amp; Pav. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chung JG, Tsou MF, Wang HH, Lo HH, Hsieh SE, Yen YS, Wu LT, Chang SH, Ho CC, Hung CF. Rhein affects arylamine N-acetyltransferase activity in Helicobacter pylori from peptic ulcer patients. J Appl Toxicol. 1998;18:117–123. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1263(199803/04)18:2<117::aid-jat486>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wang YC, Huang KM. In vitro anti-inflammatory effect of apigenin in the Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric adenocarcinoma cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;53:376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zaidi SF, Yamamoto T, Refaat A, Ahmed K, Sakurai H, Saiki I, Kondo T, Usmanghani K, Kadowaki M, Sugiyama T. Modulation of activation-induced cytidine deaminase by curcumin in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric epithelial cells. Helicobacter. 2009;14:588–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lee IO, Lee KH, Pyo JH, Kim JH, Choi YJ, Lee YC. Anti-inflammatory effect of capsaicin in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric epithelial cells. Helicobacter. 2007;12:510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Abdel-Latif MM, Windle HJ, Homasany BS, Sabra K, Kelleher D. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester modulates Helicobacter pylori-induced nuclear factor-kappa B and activator protein-1 expression in gastric epithelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:1139–1147. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]