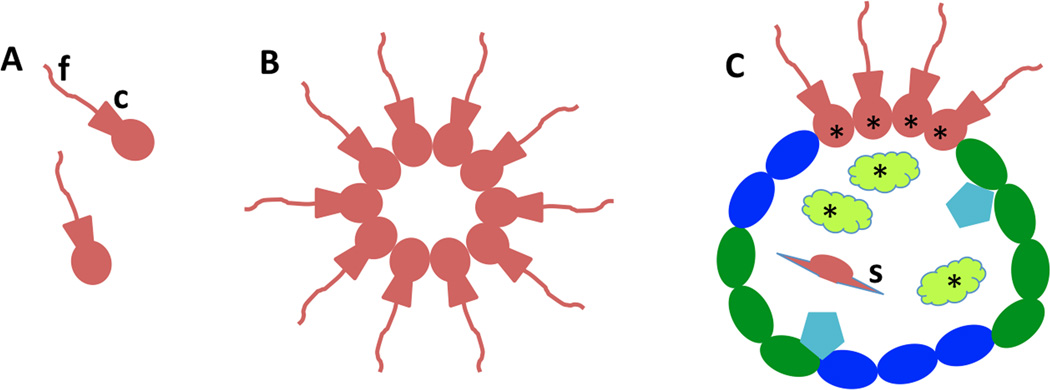

Figure 4.

Evolution of choanoflagellate colony to basal metazoans with choanocytes and archeocytes (as found in modern sponges).Single-celled choanoflagellates (A) evolved into colonial forms made of clusters or spheres of cells (B), as still living today. Note the characteristic single flagellum (f) surrounded by a collar (c) made of microvilli. The ancestral metazoan may have evolved from a similar colony. Initially, cell proliferation may have become restricted to a subset of the cells. As the metazoan evolved, cells became specialized for a variety of functions (i.e., division of labor for bodily functions; C). Continued replacement of these various cell types became the task of the ancestral somatic stem cells; in the case of sponges, these were probably choanocytes - cells that retained the basic morphology of the ancestral choanoflagellates (asterisks). As these metazoans evolved into more complex forms with both surface and interior cell types of various kinds (e.g., skeleton-forming cells such as sponge sclerocytes; s), an additional population of stem cells evolved that could migrate inside the body (asterisks; these would be the archeocytes in sponges). This combination of exterior and interior pluripotent stem cells could form an immortal cell clone, e.g., thus allowing some sponges and other basal metazoans to live for thousands of years (see text for details). Based on Funayama, 2010.