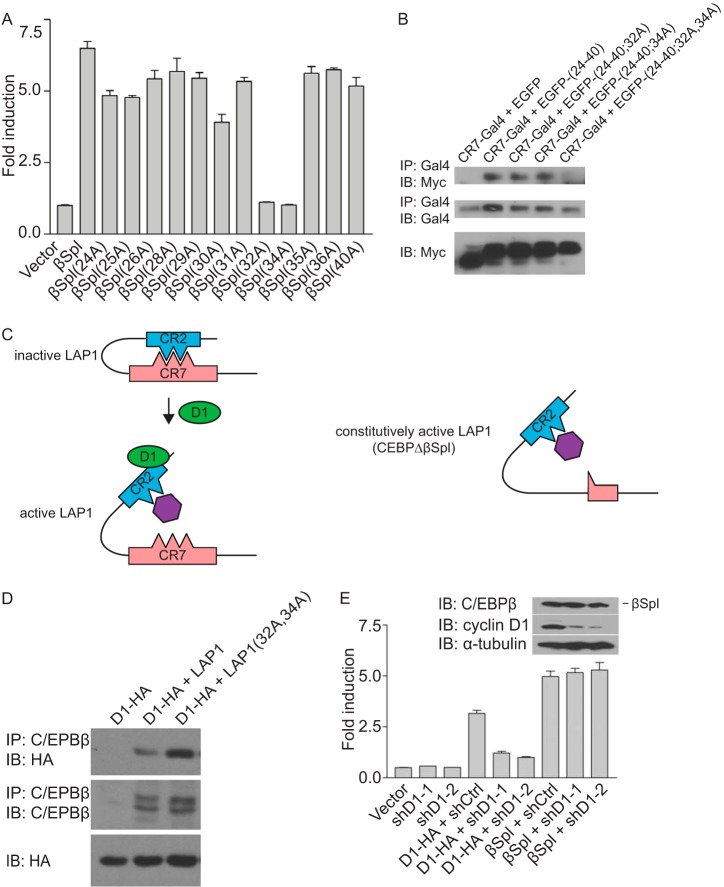

FIG 3.

Constitutively active mutant of LAP1. (A) Two acidic amino acids in CR2 are required for transcriptional induction by C/EBPβΔSpl. Alanine scanning mutagenesis was performed on aa 24 to 40 in the context of C/EBPβΔSpl. MCF-7 cells were cotransfected with a reporter construct (HSP70-2) and plasmids directing the expression of C/EBPβΔSpl (βSpl), its mutant derivatives (alanine substitution is indicated), or empty vector. Normalized promoter activity was determined 24 h later, and the fold increases in promoter activity relative to empty vector were calculated. The results are means ± the SD from three independent experiments. (B) Two amino acids in CR2 are necessary for its interaction with CR7. MCF-7 cells were cotransfected with plasmids directing the expression of Gal4 fused to amino acids 199 to 242 of LAP1 (CR7-Gal4), together with plasmids directing the expression of Myc-tagged EGFP alone or fused to aa 24 to 40 of LAP1 [EGFP-(24-40)] or derivatives of EGFP-(24-40) bearing alanine substitutions at residues E32, D34, or both designated EGFP-(24-40;32A), EGFP-(24-40;34A), and EGFP-(24-40;32A,34A). After 24 h, whole-cell lysates were prepared, and complex formation was assessed by IP with antibody to Gal4, followed by IB with antibody to the Myc epitope tag. The relative amounts of the EGFP and Gal4 fusions in whole-cell lysates were assessed with the same antibodies. The results are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Model depicting the functional interaction between cyclin D1 and LAP1, and the action of a constitutively active mutant of LAP1. In the inactive state for LAP1, CR7 binding to CR2 masks E32 and D34 in CR2; the presence of either of these acidic amino acids is required for the interaction between CR2 and CR7. Cyclin D1 binding to CR2 in LAP1 disrupts the intramolecular interaction between CR2 and CR7. This event exposes E32 and D34, permitting them to participate in the interaction with a putative transcriptional coactivator (purple, left). In the constitutively active mutant of LAP1 (C/EBPβΔSpl), the intramolecular interaction between CR2 and CR7 do not take place. Consequently, E32 and D34 are constitutively exposed, and the presence of both E32 and D34 allows CR2 to interact with a putative transcriptional coactivator (right). (D) Alanine substitution at amino acids E32 and D34 in LAP1 relieves the autoinhibited state and enhances its interaction with cyclin D1. MCF-7 cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding LAP1, a derivative of LAP1 bearing alanine substitutions as amino acids E32 and D34 [LAP1(32A,34A)], or empty vector together with a plasmid encoding HA-tagged cyclin D1 (D1-HA). After 24 h, whole-cell lysates were prepared, and complex formation was assessed by IP with antibody to C/EBPβ, followed by IB with anti-HA antibody. The relative amounts of LAP1, its mutant derivative, and cyclin D1 in whole-cell lysates were assessed with the same antibodies. The results are representative of three independent experiments. (E) C/EBPβΔSpl represents a constitutively active mutant of LAP1 that does not require cyclin D1 to effect transcription. C33A cells were infected with viruses directing the expression of one of two shRNA to cyclin D1 (shD1-1 and shD1-2) or an irrelevant shRNA (shCtrl). Subsequently, the cells were cotransfected with a reporter construct (HSP70-2), together with plasmids encoding cyclin D1-HA, C/EBPβΔSpl (βSpl), or empty vector. Normalized promoter activity was determined 24 h later, and the fold increases in promoter activity relative to empty vector were calculated. The results are means ± the SD from three independent experiments. The relative amounts of C/EBPβΔSpl and cyclin D1 under conditions where cyclin D1 was knocked down, as well as α-tubulin as a loading control, were assessed by IB (inset).