ABSTRACT

The envelope proteins of hepatitis B virus (HBV) bear an N-linked glycosylation site at N146 within the immunodominant a-determinant in the antigenic loop (AGL) region. This glycosylation site is never fully functional, leading to a nearly 1/1 ratio of glycosylated/nonglycosylated isoforms in the viral envelope. Here we investigated the requirement for a precise positioning of N-linked glycan at amino acid 146 and the functions associated with the glycosylated and nonglycosylated isoforms. We observed that the removal of the N146 glycosylation site by mutagenesis was permissive to envelope protein synthesis and stability and to secretion of subviral particles (SVPs) and hepatitis delta virus (HDV) virions, but it was detrimental to HBV virion production. Several positions in the AGL could substitute for position 146 as the glycosylation acceptor site. At position 146, neither a glycan chain nor asparagine was absolutely required for infectivity, but there was a preference for a polar residue. Envelope proteins bearing 5 AGL glycosylation sites became hyperglycosylated, leading to an increased capacity for SVP secretion at the expense of HBV and HDV virion secretion. Infectivity-compatible N-glycosylation sites could be inserted at 3 positions (positions 115, 129, and 136), but when all three positions were glycosylated, the hyperglycosylated mutant was substantially attenuated at viral entry, while it acquired resistance to neutralizing antibodies. Taken together, these findings suggest that the nonglycosylated N146 is essential for infectivity, while the glycosylated form, in addition to its importance for HBV virion secretion, is instrumental in shielding the a-determinant from neutralizing antibodies.

IMPORTANCE At the surface of HBV particles, the immunodominant a-determinant is the main target of neutralizing antibodies and an essential determinant of infectivity. It contains an N-glycosylation site at position 146, which is functional on only half of the envelope proteins. Our data suggest that the coexistence of nonglycosylated and glycosylated N146 at the surface of HBV reflects the dual function of this determinant in infectivity and immune escape. Hence, a modification of the HBV glycosylation pattern affects not only virion assembly and infectivity but also immune escape.

INTRODUCTION

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is an enveloped DNA virus and the prototype of the Hepadnaviridae family. HBV is characterized by a strict tropism for human hepatocytes and the ability to cause acute and chronic infections. It is estimated that worldwide, approximately 240 million individuals are HBV chronic carriers and are at risk of developing liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (1). HBV hepatotropism is determined, for the most part, by the HBV envelope proteins at viral entry. A single open reading frame in the HBV genome encodes three envelope proteins that differ from each other by the size of their N-terminal ectodomain. They bear the HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) in their common S domain and are referred to as the large HBsAg (L-HBsAg), middle HBsAg (M-HBsAg), and small HBsAg (S-HBsAg) proteins. They are produced in quantities far exceeding the amount needed for the assembly of HBV virions (2), and due to their capacity for self-assembly, they are secreted abundantly as empty subviral particles (SVPs). Furthermore, in the case of coinfection with the hepatitis delta virus (HDV), the HBV envelope proteins assist with the packaging and egress of the HDV ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) as HDV virions that can propagate infection. It is assumed that the envelopes of HBV and HDV particles have similar compositions, consisting of a cell-derived lipid membrane in which the HBV surface proteins are inserted (3).

All three HBV envelope proteins contain at least 2 transmembrane domains (TMDs): TMD-1 is a type 1 TMD located between residues 4 and 24 of the S domain. TMD-2 (residues 80 to 98) is a type 2 TMD that anchors the polypeptide chain into the viral membrane in the opposite direction with respect to that of TMD-1. The region located between residues 100 and 164 is translocated to the luminal compartment of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) during synthesis and displayed at the surface of secreted particles. It is referred to as the antigenic loop (AGL), which includes a single N-glycosylation site at asparagine 146. The topology of the carboxyl-terminal domain between residues 164 and 226 has not been experimentally established, but the major part, from residues 164 to 221, is hydrophobic, rich in aromatic residues, and predicted to contain 2 alpha helices (4, 5).

The AGL bears the immunodominant a-determinant, which is the first HBV marker to be identified and which is conserved in all HBV strains (6). The a-determinant is dependent upon a specific conformation of the AGL polypeptide, which is stabilized by a network of intra- and interchain disulfide bonds. It is also the primary target of HBV-neutralizing antibodies in response to vaccination or upon recovery from acute infection (7), and it is closely associated with an essential function at viral entry (8). The AGL infectivity determinant is a heparan sulfate (HS)-binding motif essential for virus attachment to the hepatocyte membrane prior to the binding of the pre-S1 domain of L-HBsAg to the sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) receptor (9).

Interestingly, the AGL amino acid sequence includes a single N-linked glycosylation site at position 146 which is strictly conserved but functional only on a fraction of the envelope proteins (approximately 50%). As a result, L- and S-HBsAg proteins consistently appear as nonglycosylated and monoglycosylated forms in the viral envelope, whereas M-HBsAg is detected as monoglycosylated and diglycosylated forms because its pre-S2 domain contains a constitutive N-linked glycosylation site. In some strains of HBV genotypes D and E, M-HBsAg is also O-glycosylated at Thr-37 (10); it is then detected as a single band of highly glycosylated protein by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), as shown in Fig. 1. M-HBsAg itself is dispensable for HBV assembly and infectivity, but M-HBsAg deprived of pre-S2-linked carbohydrates exerts a dominant negative effect on HBV virion secretion. Hence, pre-S2-linked glycans represent a potential target for antiviral therapy with α-glucosidase I inhibitors (11).

FIG 1.

HBV envelope proteins and their glycosylation patterns. (A) The secondary structure model for the HBV envelope proteins at the viral membrane (mbne), including N-linked glycans (closed circles) in the antigenic loop (AGL) and pre-S2 domain and an O-linked glycans (open circle) in the pre-S2 domain, is presented. (B) HBV envelope proteins derived from SVPs produced in Huh-7 cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis using a rabbit R247 anti-S antibody. Note that HBV envelope proteins of genotype A (adw2 subtype) and genotype D (ayw3 subtype) bear one and two glycosylation sites in the pre-S2 domain, respectively. The glycosylated (gp) and nonglycosylated (p) forms of S-HBsAg (S), M-HBsAg (M), and L-HBsAg (L) proteins are indicated. Note that the gggpM and ggpM isoforms of M-HBsAg genotype D ayw3 comigrate as gp36 in SDS-polyacrylamide gels. (C) Schematic representation of the different isoforms of the HBV genotype D envelope proteins (ayw3 subtype). (D) Schematic representation of the genotype A M-HBsAg protein (adw2 subtype).

There could be many reasons for the conservation of the AGL glycosylation pattern with regard to both the position of the glycosylation site in the AGL sequence and its partial usage. In general, N-glycosylation is important for protein folding, quality control, sorting, degradation, and secretion, and surface proteins of enveloped viruses often undergo N-glycosylation for efficient production, stability, and function in particle assembly or infectivity. In addition, several enveloped viruses use glycosylation as a means for evading neutralizing antibodies by building a glycan shield at the surface of the virion (12, 13). For instance, the HIV virion surface bears few envelope proteins, but the envelope proteins are heavily glycosylated for efficient evasion of the immune response (14). HBV, in contrast, displays many surface proteins, and these are nonglycosylated and N-glycosylated at only one or two positions.

HBV may also escape the immune response by undergoing mutations that create additional N-glycosylation sites in the AGL, as described recently in a Chinese cohort of chronically infected patients (15).

N-linked glycans at N146 in HBV envelope proteins were shown to be dispensable for the secretion of SVPs or HDV virions (16–18) but important for that of HBV virions (19). However, position 131 can substitute for position 146 as the glycosylation site without compromising virion secretion (19). In this study, we investigated the function associated with the unique pattern of HBV envelope protein glycosylation by measuring the effect of changing the position or the number of AGL-linked glycans on HBV/HDV particle assembly, infectivity, and susceptibility to neutralizing antibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Plasmid pSVLD3 was used for HDV RNA replication and the production of HDV RNP (20) in Huh-7 cells. Plasmid pCIHBEnv(−) was used for the production of HBV nucleocapsid, as described previously (21), and plasmid pT7HB27 was used for expression of wild-type (wt) HBV L-, M-, and S-HBsAg proteins. Plasmids p123 and p201 are derived from pT7HB27 for expression of wt and glycosylation-deficient S-HBsAg, respectively. Mutant plasmids were generated from pT7HB27, p123, or p201 by site-directed mutagenesis using the overlapping PCR technique with two complementary mutagenic oligonucleotides, as described previously (22).

Expression of HBV envelope proteins and production of HBV and HDV particles.

Expression of HBV envelope proteins and production of HBV and HDV particles were achieved in Huh-7 cells as previously described (23). Cells (106/well) were transfected with 1 μg each of plasmids pSVLD3, p123, and p124 (or their derivatives) (17). Transfection was carried out using the Fugene-HD reagent according to the manufacturer's directions (Roche). Culture supernatants were harvested at days 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 posttransfection, pooled, and analyzed by immunoblotting for the detection of HBV envelope proteins (23). Note that detection of HBV envelope proteins was achieved using the H166 monoclonal antibody (MAb) (24) or the rabbit R247 polyclonal anti-S antibody (25). When indicated, peptide-N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) treatment of envelope proteins was performed as previously reported (23). Supernatants harvested at days 11, 13, and 15 posttransfection were analyzed for the production of HDV or HBV virions by measuring the levels of HDV RNA by Northern blotting or HBV DNA by Southern blotting after anti-pre-S1 antibody immunoprecipitation to exclude DNA from nonenveloped nucleocapsids (23). HDV virion-containing supernatants served as inocula in infectivity assays after normalization for their HDV RNA content by Northern blotting.

Metabolic labeling, pulse-chase, and immunoprecipitation.

Huh-7 cells were labeled with [35S]Cys, and immunoprecipitation was achieved as described previously (25). In brief, at 2 days posttransfection, Huh-7 cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]Cys for 1 h. The labeling medium was then removed and replaced with William's medium E containing 10% fetal calf serum. At various intervals, cells and culture medium were harvested and treated as described previously (25) for immunoprecipitation with anti-HBsAg (R247) antibodies. Immune complexes were isolated after incubation for 1 h at 4°C with a 10% (wt/vol) suspension of protein A-Sepharose (Sigma), and proteins were eluted from the beads by boiling in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8)–2% SDS–0.1% bromophenol blue–10% glycerol–5% beta-mercaptoethanol. After SDS-PAGE, the gel was fixed, dried, and subjected to fluorography at −70°C.

In vitro infection assay.

HepaRG cells were cultured as described previously (26). For infection with HDV virions, clarified supernatants from Huh-7 cells were used for infection after normalization for HDV RNA. HepaRG cells (106 cells/well) were exposed to approximately 108 genome equivalents (ge) of HDV virions for 16 h in the presence of 4% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 (Sigma). Cells were harvested at day 9 postinoculation in RLT buffer (Qiagen). Total cellular RNA was purified using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) and tested for the presence of genomic HDV RNA as evidence of infection, as described previously (27).

ELISA.

For quantification of viral particles by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), each well of a 96-well MaxiSorp plate (Nunc) was coated with viral particles by adding 10 μl per well of a 20-fold-concentrated preparation of supernatant from transfected cells in 100 μl of 50 mM NaHCO3 buffer, pH 9.6. Plates were then processed as described previously (8). Detection of bound viral particles was achieved using anti-HBsAg H166 MAb, which recognizes a conserved linear epitope in the AGL. For testing the effect of additional AGL-linked glycans, a panel of anti-a-determinant-specific MAbs was selected: A1.2, A2.1, and control anti-HIV gp120 (gifts from R. Kennedy [28]), MAbs 9701, 9705, 9709, and A5 (Biodesign), MAb H166 (Abbott), and MAb 4-7B (29). Anti-pre-S1 MAb MA18/7 and anti-pre-S2 MAb Q19/10 were gifts from W. Gerlich (30).

RESULTS

The HBV envelope proteins are glycosylated at position 146 in the S domain, but only a fraction (approximately 50%) of the proteins bears N146-linked glycans. Both the amino acid at position 146 and partial glycosylation are conserved characteristics that strongly suggest an important underlying function of this glycosylation pattern in the HBV life cycle. Each of the L- and S-HBsAg proteins was detected in the unglycosylated and glycosylated forms, with an approximate 1:1 stoichiometry for S-HBsAg, whereas L-HBsAg was preferentially detected in its glycosylated form (Fig. 1).

The lack of N146-linked carbohydrates has no effect on HBV envelope protein synthesis, stability, or rate of secretion.

As previously documented, the lack of glycosylation at N146 does not severely affect the overall level of extracellular SVPs in cell culture (17). In the experiment whose results are reported here, when HBV envelope proteins expressed in Huh-7 cells were analyzed by pulse-chase labeling and immunoprecipitation, there was no difference between the wt and N146T mutant proteins with regard to the steady-state level of synthesis or the rate of SVP secretion, confirming that N146-linked glycans do not play a major role in quality control or the stability of the HBV envelope protein and SVP assembly and secretion (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Synthesis and secretion of wt and mutant (N146T) HBV envelope proteins. Two days after transfection of Huh-7 cells with plasmid DNA carrying the sequences for wt or N146T mutant HBV envelope proteins, cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]Cys for 1 h, and labeling was chased for the indicated time period before harvesting (22). (Top and middle) Labeled proteins from cell lysates (lanes C) and culture medium (lanes M) were immunoprecipitated with rabbit R247 anti-S antibodies and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the gel was dried and subjected to fluorography at −70°C for 48 h. X-ray films were scanned, and signals for the wt or N146T S-HBsAg were quantified using ImageJ software for image processing. (Bottom) The secretion rate is expressed as the amount of protein from culture as a percentage of the amount of protein from cell lysates plus the amount of protein from the culture medium for the wt-LMS or the N146T-LMS mutant. The glycosylated (gp) and nonglycosylated (p) forms of S-, M-, and L-HBsAg (LMS) are indicated.

The AGL glycosylation acceptor site is functional at positions other than position 146 in the AGL sequence.

To assess the importance of the precise positioning of the AGL glycosylation site at residue 146, we constructed S-HBsAg mutants bearing an NGT sequon at different positions throughout the AGL sequence (positions 114, 121, 129, 135, and 144). This was achieved by substituting an NGT sequon for the wt sequence in the glycosylation-deficient N146T S-HBsAg protein (17). As controls, we created mutants bearing an NGT sequon within the cytosolic loop (position 40 or 52) or within the C-terminal end of S-HBsAg (positions 165, 172, 185, 191, 202, or 208), predicted to be membrane associated. As shown in Fig. 3, all mutants were expressed in Huh-7 cells and secreted as efficiently as SVPs. Interestingly, all NGT sequons introduced in the AGL sequence (positions 114 to 144) were functional glycosylation acceptors, but as was observed for wt S-HBsAg, full glycosylation was not achieved for most of the mutants. Only the most N-terminal position (NGT at position 114) allowed a nearly complete N-glycosylation. Then, the glycosylation efficiency appeared to decrease as the proximity of the acceptor site to the hydrophobic, membrane-associated C terminus of S-HBsAg increased. Although sequons at positions 165, 172, and 185 were located within a region described to be surface exposed (29), none of them were efficient substrates for N-glycosylation. As expected, sequons located within the hydrophobic C terminus of S-HBsAg (positions 191, 202, and 208), clearly predicted to be membrane associated, remained ineffective. We concluded that the limited efficiency of N146 as a glycosylation acceptor site is due, at least in part, to its proximity to the membrane-associated C-terminal domain (positions 154 to 202) (4).

FIG 3.

S-HBsAg is permissive to insertion of novel N-glycosylation sequons (NGT) at several positions in the AGL. Huh-7 cells were transfected with plasmid DNA for the expression of wt or mutant S-HBsAg proteins. After transfection, supernatants were analyzed for the presence of HBV envelope proteins by Western blot analysis as described previously (32). The amino acid sequence of S-HBsAg, including the positions of the different NGT insertions, is indicated.

The lack of N-linked glycan at AGL position 146 is permissive to secretion of SVPs and HDV virions but detrimental to that of HBV virions.

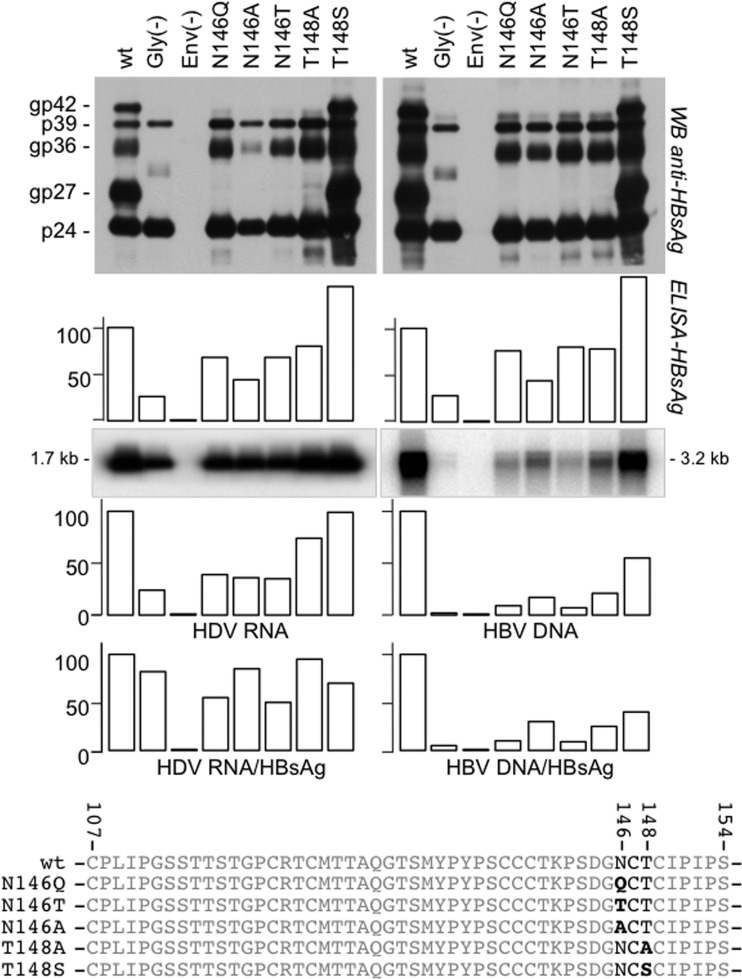

Since our analysis of AGL glycosylation is based on mutagenesis, the effect of an amino acid residue substitution at N146 may reflect the absence of carbohydrates at position 146 or the modification of the amino acid (aa) 146 side chain. To address this question, several mutants with S-HBsAg mutations (N146Q, N146T, N146A, T148A, and T148S) were created. They were found to be competent for SVP assembly and secretion and demonstrated the expected unglycosylated profile for the N146Q, N146T, N146A, and T148A mutants (Fig. 4) and the wt glycosylation pattern for the T148S mutant. The latter mutant, however, demonstrated a 50% increase in SVP synthesis/secretion efficiency. When coexpressed with HDV RNP in Huh-7 cells, we observed no drastic change in the efficiency of the mutants for HDV virion assembly and release compared to that of wt S-HBsAg. However, when coexpressed with the HBV nucleocapsid, the glycosylation-defective mutants were clearly impaired for HBV virion assembly and release, as reported previously (19). Because virion assembly efficiency was measured by use of the ratio of HBV DNA/HBsAg in cell culture supernatants, T148S envelope proteins, which are better secreted as SVPs than wt proteins, appeared to be less efficient than wt envelope proteins for HBV virion assembly. We concluded that it is indeed the absence of a carbohydrate chain at N146 which is detrimental to HBV virion secretion and not the change of the side chain at aa 146, since glycosylation-deficient T148A proteins were also impaired for HBV virion release. Note that T148S proteins were more efficient than wt proteins at SVP secretion but were less efficient for virion assembly. This is consistent with SVPs and HBV virions being released from the cells through distinct routes: the cell secretory pathway for SVPs and HDV virions and the multivesicular body (MVB) pathway for HBV virions (31).

FIG 4.

Effects of amino acid substitutions at N146 in the HBV envelope proteins on secretion of HBV and HDV particles. Huh-7 cells were transfected with a mixture of DNA from plasmid pT7HB2.7 or its derivatives for the expression of wt or mutant HBV envelope proteins, respectively, and (i) pSVLD3 for the production of HDV particles (left) or (ii) pCIHBenv(−) for the production of HBV particles (right). After transfection, supernatants were analyzed for the presence of envelope proteins by Western blotting (WB) before and after incubation with PNGase F, as indicated, or by an HBsAg-specific ELISA and for HDV RNA by Northern blotting analysis and HBV DNA by Southern blotting analysis. The histograms show the amounts (in percent) of secreted SVPs relative to that for the wt measured with an anti-HBsAg ELISA (DiaSorin); HDV RNA and HBV DNA were measured by Northern and Southern blot analyses, respectively. The glycosylated (gp) and nonglycosylated (p) forms of S-HBsAg (p24, gp27), M-HBsAg (gp36), and L-HBsAg (p39, gp42) are indicated. Gly(−), transfection conducted with plasmid DNA carrying the sequences for HBV envelope proteins lacking glycosylation sites in pre-S2 (substitutions N4Q, T37A, and T38S in pre-S2) and S (substitution N146Q in the AGL); Env(−), transfection conducted in the absence of the plasmid carrying the sequences for envelope proteins. The amino acid sequences of the wt and mutant AGLs, including the substitutions at positions 146 and 148, are indicated.

The absence of N146-linked glycan in the HBV envelope proteins is permissive to HDV infectivity.

To further analyze the effect of N146-linked glycan on infectivity, we used HDV particles bearing the above-mentioned substitutions for in vitro infection of HepaRG cells. Assays were conducted as described previously (23) after normalization of the inocula for HDV RNA. As shown in Fig. 5, full infectivity was preserved in the absence of AGL-linked glycans for N146Q, as previously reported (17). The reason for the partially reduced infectivity of particles bearing nonglycosylated T148A and, to a lesser extent, those bearing N146A was thus assigned not to the lack of glycan but to the change to the amino acid side chain. Our conclusion is that the N146-linked glycan does not contribute to the AGL infectivity determinant but that the nature of the amino acid side chain at positions 146 and 148 does and that the preference is for polar over apolar residues.

FIG 5.

Infectivity of HDV particles bearing amino acid substitutions in the AGL glycosylation site of HBV envelope proteins. Inocula were normalized for HDV RNA by Northern blotting hybridization. HepaRG cells (106 cells) were exposed to approximately 108 ge of HDV particles. At day 9 postinoculation (postino), cellular RNA was analyzed for the presence of HDV RNA. Signals were quantified using a phosphorimager. The values in the histograms represent the averages and standard deviations from three independent experiments. wt, HDV particles coated with wt S-, M-, and L-HBsAg; S-HDV, HDV particles coated with wt S-HBsAg. Gly(−) and Env(−) are defined in the legend to Fig. 4.

Hyperglycosylation of HBV envelope proteins increases SVP secretion at the expense of virion secretion.

To investigate further the advantage conferred by AGL-linked glycans to HBV or HDV, we tested whether increasing the number of glycosylation acceptor sites in the AGL would affect the capacity of HBV envelope proteins for SVP and virion assembly/secretion. We created a mutant bearing 5 glycosylation sites (N-5) in the AGL and a control mutant, designated Q-5, in which the asparagines of the N-5 glycosylation sites were changed to glutamines (with the authentic glycosylation site at position 146 being preserved in Q-5) (Fig. 6). NGT or QGT sequons were introduced into the AGL at positions previously shown to tolerate amino acid substitution/insertion (8, 32). N-5 envelope proteins were hyperglycosylated and detected as SVPs in the culture medium (Fig. 6). We observed a 70% increase in the N-5 capacity for SVP assembly/secretion but a nearly 75% decrease for virion (HBV and HDV) assembly and release. Interestingly, both the N-5 and the Q-5 mutants demonstrated a loss of both the a-determinant (measured with a commercial HBsAg ELISA) and the infectivity determinant (tested at the surface of HDV particles in an in vitro infection assay) (data not shown).

FIG 6.

Impact of hyperglycosylation of HBV envelope proteins on HBV and HDV particle secretion. Huh-7 cells were transfected with a mixture of DNA from plasmid pT7HB2.7 or its derivatives for the expression of wt or mutant HBV envelope proteins, respectively, and (i) pSVLD3 for the production of HDV particles (left) or (ii) pCIHBenv(−) for the production of HBV particles (right). After transfection, supernatants were analyzed for the presence of HBV envelope proteins by Western blot analysis (WB) before and after incubation with PNGase F, as indicated, or by an HBsAg-specific ELISA and for HDV RNA by Northern blotting analysis and HBV DNA by Southern blotting analysis. The values in the histograms represent averages and standard deviations from three independent experiments and show the amounts of extracellular, virion-associated HBV DNA or HDV RNA relative to that of the wt. The glycosylated (gp) and nonglycosylated (p) forms of S-HBsAg (p24, gp27), M-HBsAg (gp36), and L-HBsAg (p39, gp42) are indicated. The amino acid sequences of the wt and mutant AGLs are indicated. IP, immunoprecipitation.

Hyperglycosylation of HBV envelope proteins reduces infectivity.

Given that the AGL plays a crucial role at viral entry (33), we wished to examine whether the presence of multiple AGL-linked glycans could affect infectivity. Prior to addressing this question, we had to identify individual positions in the AGL polypeptide that would tolerate the introduction of a novel glycosylation acceptor site without affecting infectivity. Based upon our previous mapping of the AGL infectivity determinant (8), we selected positions 115, 129, and 136 to create the following respective mutants: NG115–N146T, Q129N-N146T, and NG136–N146T. As shown in Fig. 7, the mutants bear a single glycosylation site in the AGL at positions 115, 129, and 136, respectively (with the N146 site having been eliminated by the N146T substitution). All mutants were indeed permissive for the production of SVPs and HDV particles that were infectious in vitro. We then created mutants bearing either (i) two glycosylation sites, at positions 129 and 146 (Q129N) or 136 and 146 (NG136), or (ii) four glycosylation sites, at positions 115, 129, 136, and 146 (G4). As shown in Fig. 8, efficient glycosylation was observed for each mutant including G4 envelope proteins that mainly appeared under 3 glycoforms bearing 2, 3, and 4 N-linked glycans, respectively. When tested at the surface of HDV particles for function at viral entry, only G4 proteins were partially impaired for infectivity, suggesting that the high density of glycans at the virion's surface would interfere with entry.

FIG 7.

Impact of changing the position of N-linked glycan in the AGL on infectivity. Production of wt or mutant HDV particles was achieved by transfection of Huh-7 cells. Culture fluids from transfected cells were assayed for the presence of HBV envelope proteins by immunoblot analysis and HDV RNA by Northern blotting (inoculum). HepaRG cells were exposed to wt and mutant HDV particles after normalization of the inocula for HDV RNA. At day 9 postinoculation, cells were harvested and cellular RNA was analyzed by Northern analysis. Quantification of HDV RNA signals was achieved using a phosphorimager. The values in the histogram are expressed as percentages of the wt value. The glycosylated (gp) and nonglycosylated (p) forms of S-HBsAg (S) and L-HBsAg (L) proteins are indicated. wt LMS, HDV particles coated with wt L-, M- and S-HBsAg; S-HDV, particles coated with the S-HBsAg only. The amino acid sequences of the wt and mutant AGLs are indicated. The positions of N-linked glycosylation sites are indicated in bold type.

FIG 8.

Impact of AGL hyperglycosylation on infectivity of HDV particles. (A) The amino acid sequences of the wt and mutant AGLs are indicated. The positions of N-linked glycosylation sites are indicated in bold type. The N-glycosylation sites (closed circles) are indicated on a schematic representation of wt and mutant AGLs. (B) Production of wt or mutant HDV particles was achieved by transfection of Huh-7 cells. Culture fluids (supernatants [sup]) from transfected cells were assayed for the presence of HBV envelope proteins by Western blotting before and after incubation with PNGase F, as indicated, and for HDV RNA by Northern blotting. (C) HepaRG cells were exposed to wt and mutant HDV particles after normalization of the inocula for HDV RNA. At day 9 postinoculation, cellular RNA was analyzed by Northern analysis. Quantification of HDV RNA signals was achieved using a phosphorimager. The values in the histograms represent the averages and standard deviations from three independent experiments. The position of HDV RNA is indicated. The glycosylated (gp) and nonglycosylated (p) forms of S-HBsAg (S) and L-HBsAg (L) proteins are indicated. wt LMS, HDV particles coated with wt L-, M- and S-HBsAg; S-HDV, particles coated with the S-HBsAg only.

Effect of hyperglycosylation in the AGL on reactivity with anti-a-determinant antibodies.

Since the AGL—and the a-determinant in particular—is the main target of neutralizing anti-HBsAg antibodies, we sought to determine whether hyperglycosylation of the AGL could prevent binding of anti-HBsAg antibodies. For this, we selected 5 anti-HBs MAbs known to bind epitopes of the a-determinant (MAbs A1.2, A2.1, 9701, 9705, and 9709) and compared their reactivity relative to that of an anti-pre-S1 MAb (MAb MA18/7) as a control. Preparations of wt and mutant L-, M-, and S-HBsAg (LMS) SVPs were normalized for the envelope protein concentration using (i) a pre-S2-specific ELISA (8), (ii) an AGL-specific ELISA with MAb H166 that recognizes a linear epitope in the AGL, and (iii) immunoblot analysis (Fig. 8). Reactivity to anti-a-determinant MAbs was then assessed as described previously (8). Clearly, the G4 mutant (with 4 glycosylation sites) was no longer reactive with 4 of the 5 anti-HBsAg MAbs (MAbs A1.2, A2.1, 9701, and 9705) and only partially reactive with MAb 9709 (Fig. 9). Interestingly, the presence of 4 glycosylation sites appeared to be detrimental to anti-pre-S1 binding, indicating that a high density of N-linked glycans at the surface of viral particles could either shield the N terminus of pre-S1 from antibody recognition or induce an allosteric effect on the pre-S1 structure or topology at the viral membrane. The fact that nonglycosylated N146Q was not recognized or was only poorly recognized by several anti-a-determinant MAbs (MAbs A1.2, 9701, and 9709) indicates that most epitopes of the a-determinant include N146. Surprisingly, the absence of N146 glycan (N146Q) affected binding of anti-pre-S1 antibodies to SVPs. This may indicate a role of N146-linked glycans in the surface exposure of pre-S1. Overall, our results show that additional glycans in the AGL can shield surface-exposed epitopes.

FIG 9.

Specific antigenicity of subviral particles bearing amino acid substitutions in the AGL. The histograms show the effect of additional N-linked glycosylation sites in the AGL on SVP reactivity with anti-HBsAg MAbs A1.2, A2.1, 9701, 9705, and 9709 and anti-pre-S1 MAb MA18/7. A pre-S2 ELISA was used to normalize preparations of particles for their content in HBV envelope proteins prior to being subjected to the MAb-specific ELISA. Values are given as percentages relative to that for the wt. Reactivities are the averages from 3 independent experiments.

AGL hyperglycosylation prevents virus neutralization with anti-a-determinant MAbs.

We sought to directly evaluate whether AGL hyperglycosylation could protect from neutralization with anti-HBsAg antibodies in an in vitro infection assay. We selected eight anti-HBs MAbs (MAbs A1.2, A2.1, 9701, 9705, 9709, A5, H166, and 4-7B) and controls (anti-pre-S1 MAb MA18/7, anti-pre-S2 MAb Q19/10, and anti-gp120 directed against the HIV-1 gp120 envelope protein) (28). Antibodies were tested at 0.05 μg/ml, a concentration previously determined to be within the linear phase of the dose-dependent neutralization response. As shown in Fig. 10, most anti-HBsAg MAbs demonstrated a lack of or reduced neutralizing activity with hyperglycosylated G4 HDV (glycans at positions 115, 129, 136, and 146). The fact that most antibodies could neutralize Q129 HDV particles (glycosylated at positions 129 and 146) suggests that carbohydrates at position 115 and/or 136 are the most effective in shielding epitopes of the a-determinant. From the results of this experiment, we concluded that AGL N-linked glycans might serve to shield the AGL from neutralizing anti-HBsAg antibodies.

FIG 10.

Hyperglycosylation of the HBV envelope proteins. AGL prevents HDV neutralization with anti-HBsAg MAbs. Histograms represent the levels of HDV RNA in HepaRG cells at day 9 after inoculation with the wt or N146, Q129N, or G4 glycosylation mutant. Inoculation was conducted in the presence of anti-HBsAg MAbs A1.2, A2.1, 9701, 9705, 9709, A5, H166, and 4-7B; anti-pre-S1 MAb MA18/7; anti-pre-S2 Q19/10; and anti-HIV gp120 at a 0.05-μg/ml concentration. Infection levels were defined as ratios (in percent) of the mean values from 3 experiments to the mean value for the negative control.

DISCUSSION

The two HBV envelope proteins (L- and S-HBsAg) that are required for assembly of infectious virions (34) bear a single N-glycosylation site in the AGL domain and display a glycosylation pattern that is conserved across genotypes and throughout the course of an infection. Only in a few cases of chronic infection is this pattern modified to include an additional site (35), a strategy used more extensively by other enveloped viruses, such as HIV or hepatitis C virus, to escape neutralizing antibodies (13). In this study, the functions underlying the peculiar glycosylation pattern of HBV envelope proteins were explored, in particular with respect to position 146 in the AGL at which N-glycosylation occurs and the systematic coexistence of glycosylated and nonglycosylated N146.

The absence of N146 glycans affected neither the kinetics and steady-state levels of envelope protein synthesis nor the SVP secretion level (Fig. 2), but it led to a decrease in HBV virion production, as previously reported (35). This defect was not due to the reduced synthesis or stability of the nonglycosylated L-HBsAg mutant compared to that of the wt. Rather, it likely resulted from a topology of the pre-S1/pre-S2 matrix domain at the ER membrane that is not compatible with binding to the nucleocapsid for virion assembly (36).

In theory, the HBV envelope proteins should tolerate additional glycosylation sites in such domains as those from positions 101 to 117, 125 to 136, and 143 to 145 that we previously documented to be nonessential to the AGL infectivity determinant (8). Within these regions, the 113-SSTTST-118 sequence appears to be the best suited for the emergence of a novel N-glycosylation site, since a single nucleotide mutation in the DNA coding sequence would suffice to create an NXT/S sequon at position 113, 114, 115, or 116. However, the relatively limited frequency at which HBV utilizes the strategy of N-glycosylation mutant selection as a means for immune escape may lie with the fact that the mutations must not only be compatible with infectivity but also preserve the function of the HBV polymerase encoded by the overlapping gene in the minus-one frame. Yet, in a few cases of chronic infections, the emergence of extra glycosylation sites within the AGL has been described (15, 19, 37). For example, NXT/S insertion at position 115 or substitution of an asparagine residue at position 129, 130, or 131 was shown to confer immune escape in HBV chronic carriers. In the present study, HDV mutants bearing an NGT sequon at position 115 or 129 were infectious in tissue culture, indicating that mutants bearing extra glycosylation sites could be horizontally transmitted (15). Such variants could be difficult to detect by conventional HBsAg assays, poorly transmitted because of an impaired infectivity, and eventually, responsible for occult infection (38).

Contrary to our expectation, on the basis of the findings of a previous study (15, 19), overglycosylation of the envelope proteins while increasing SVP release leads to a decrease in virion production for both HDV and HBV. It has been shown that HBV virions bud at intracellular membranes with the assistance of the functions of host multivesicular bodies (MVBs), while SVP secretion occurs through the constitutive secretory pathway independently of the function of MVB proteins (31). Thus, hyperglycosylation could enhance SVP release through the secretory pathway and thereby deprive the MVB pathway of envelope proteins. However, the fact that secretion of hyperglycosylated HDV virions was impaired was surprising because it was thought to occur through the SVP secretory pathway. This assumption was based upon similarities between HDV virions and SVPs: (i) the protein composition of the HDV virion envelope is similar to that of SVPs and different from that of the HBV virion in that it bears less L-HBsAg, and (ii) the concentration of HDV virions (up to 1011/ml) in infectious serum is closer to that of SVPs (up to 1013/ml) than it is to that of HBV virions (109/ml). However, our results clearly show a decrease in HDV virion release in the presence of hyperglycosylated envelope proteins, suggesting that HBV and HDV share common host factor requirements for virions released through the MVB pathway.

Interestingly, in our model, position 146 in the AGL polypeptide was not the most effective for N-linked glycosylation. Upstream positions appear to acquire functionality with an increase in their distance from position 146. This is reminiscent of the general observation made by Nilsson and von Heijne (39), who linked glycosylation efficiency at a given NXS/T sequon to its distance from the protein carboxyl terminus and to the presence of a downstream membrane-associated domain. Other factors are known to influence the efficiency of an NXS/T signal in driving glycosylation; for instance, the X residue, which happens to be a cysteine in the AGL polypeptide, is known to be engaged in disulfide bridging essential to the definition of both the a-determinant and the infectivity determinant. Disulfide bonds in the vicinity of the glycosylation site sequon may also play a role, as previously observed (32, 40). Other residues, such as charged or large hydrophobic amino acids, at the X position may interfere with glycosylation efficiency. Interestingly, an NCS sequon at position 146 is more efficient than the wt NCT sequon.

As shown in Fig. 3 and 7, the transfer of the glycosylation site to position 115 leads >90% of each L- or S-HBsAg protein to undergo glycosylation without consequences on virion assembly or infectivity. Therefore, full glycosylation per se, irrespective of the glycan's position in the AGL, is not detrimental at any step of the replication cycle in vitro. Then, the fact that the proportion of glycosylated N146 is always limited indicates that nonglycosylated N146 is functionally important. Clearly, neither the asparagine residue nor carbohydrates at position 146 are required for infectivity, but there is a preference for a polar amino acid residue at positions 146 and 148 (Fig. 5). These residues are located in the vicinity of K141, a crucial element of the AGL HS-binding site (33), and they may participate, along with R122, in the definition of the HS-binding site on the nonglycosylated AGL isoform. Because the AGL domain surrounding N146 is highly antigenic (41) and therefore prone to elicit the production of potent neutralizing antibodies, it should be to the advantage of the virus to shield as many neutralizing epitopes as possible through glycosylation, leaving the minimum amount of nonglycosylated N146 for infectivity.

We succeeded in creating several mutants with novel N-glycosylation sites, but when up to 4 of these sites were associated on the same polypeptide, infectivity was affected. It is possible that, individually, the novel glycosylation sites would not affect the AGL structure but could well do so when present together on the same molecule. More likely, the global negative charge borne by 4 oligosaccharide chains could prevent AGL from binding to negatively charged HS. Although they were partially impaired for infectivity, hyperglycosylated virions acquired resistance to several neutralizing MAbs. Again, this can be due either to a loss of the a-determinant through modification of the three-dimensional structure of AGL or to shielding by the polysaccharide chains. However, in the case of NG136, which bears a single extra glycan at position 136, infectivity was preserved, while accessibility to neutralizing MAbs was lost. This is in agreement with the preservation of a functional NG136-AGL structure shielded from antibody binding by the N136 sugar moiety.

The fact that anti-pre-S1 MAb MA18/7 is less reactive with the G4 mutant (Fig. 9) may also be the consequence of the presence of a dense glycan shield at the viral surface. Eventually, the carbohydrates or the amino acid substitutions that create the glycosylation signals could allosterically modulate the conformation of the pre-S1 determinant. It should be noted that the epitope recognized by MAb MA18/7 is located at the N terminus of pre-S1, which is thought to lie close to the lipid membrane, assuming that the N-terminal myristate moiety is anchored to the viral membrane. The apparent lack of reactivity between N146Q particles and MAb MA18/7 may be explained by a depletion of surface-exposed pre-S1.

Taken together, our results suggest that the 1/1 ratio of glycosylated/nonglycosylated N146, as typically observed in the HBV envelope proteins, is probably the result of a fine-tuned balance between (i) the functions of the glycosylated form in virion assembly and shielding of neutralizing epitopes and (ii) the function of nonglycosylated N146 at viral entry. Further extension of AGL glycosylation as a means of immune escape would come at the cost of infectivity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le Sida et les Hepatitis Virales (ANRS). R.J. was an ANRS research fellowship recipient.

We thank Wolfram Gerlich, Ronald Kennedy, and Mark van Roosmalen for the gift of monoclonal antibodies.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 June 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST. 2012. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine 30:2212–2219. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruss V. 2007. Hepatitis B virus morphogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 13:65–73. 10.3748/wjg.v13.i1.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonino F, Heermann KH, Rizzetto M, Gerlich WH. 1986. Hepatitis delta virus: protein composition of delta antigen and its hepatitis B virus-derived envelope. J. Virol. 58:945–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Persson B, Argos P. 1994. Prediction of transmembrane segments in proteins utilising multiple sequence alignments. J. Mol. Biol. 237:182–192. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stirk HJ, Thornton JM, Howard CR. 1992. A topological model for hepatitis B surface antigen. Intervirology 33:148–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norder H, Courouce AM, Coursaget P, Echevarria JM, Lee SD, Mushahwar IK, Robertson BH, Locarnini S, Magnius LO. 2004. Genetic diversity of hepatitis B virus strains derived worldwide: genotypes, subgenotypes, and HBsAg subtypes. Intervirology 47:289–309. 10.1159/000080872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanetti AR, Van Damme P, Shouval D. 2008. The global impact of vaccination against hepatitis B: a historical overview. Vaccine 26:6266–6273. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salisse J, Sureau C. 2009. A function essential to viral entry underlies the hepatitis B virus “a” determinant. J. Virol. 83:9321–9328. 10.1128/JVI.00678-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan H, Zhong G, Xu G, He W, Jing Z, Gao Z, Huang Y, Qi Y, Peng B, Wang H, Fu L, Song M, Chen P, Gao W, Ren B, Sun Y, Cai T, Feng X, Sui J, Li W. 2012. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. eLife 1:e00049. 10.7554/eLife.00049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitt S, Glebe D, Alving K, Tolle TK, Linder M, Geyer H, Linder D, Peter-Katalinic J, Gerlich WH, Geyer R. 1999. Analysis of the pre-S2 N- and O-linked glycans of the M surface protein from human hepatitis B virus. J. Biol. Chem. 274:11945–11957. 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Block TM, Lu X, Platt FM, Foster GR, Gerlich WH, Blumberg BS, Dwek RA. 1994. Secretion of human hepatitis B virus is inhibited by the imino sugar N-butyldeoxynojirimycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:2235–2239. 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anjum S, Wahid A, Afzal MS, Albecka A, Alsaleh K, Ahmad T, Baumert TF, Wychowski C, Qadri I, Penin F, Dubuisson J. 2013. Additional glycosylation within a specific hypervariable region of subtype 3a of hepatitis C virus protects against virus neutralization. J. Infect. Dis. 208:1888–1897. 10.1093/infdis/jit376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vigerust DJ, Shepherd VL. 2007. Virus glycosylation: role in virulence and immune interactions. Trends Microbiol. 15:211–218. 10.1016/j.tim.2007.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reitter JN, Means RE, Desrosiers RC. 1998. A role for carbohydrates in immune evasion in AIDS. Nat. Med. 4:679–684. 10.1038/nm0698-679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu DM, Li XH, Mom V, Lu ZH, Liao XW, Han Y, Pichoud C, Gong QM, Zhang DH, Zhang Y, Deny P, Zoulim F, Zhang XX. 2014. N-Glycosylation mutations within hepatitis B virus surface major hydrophilic region contribute mostly to immune escape. J. Hepatol. 60:515–522. 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta A, Lu X, Block TM, Blumberg BS, Dwek RA. 1997. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) envelope glycoproteins vary drastically in their sensitivity to glycan processing: evidence that alteration of a single N-linked glycosylation site can regulate HBV secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:1822–1827. 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sureau C, Fournier-Wirth C, Maurel P. 2003. Role of N glycosylation of hepatitis B virus envelope proteins in morphogenesis and infectivity of hepatitis delta virus. J. Virol. 77:5519–5523. 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5519-5523.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang CJ, Sung SY, Chen DS, Chen PJ. 1996. N-linked glycosylation of hepatitis B surface antigens is involved but not essential in the assembly of hepatitis delta virus. Virology 220:28–36. 10.1006/viro.1996.0282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito K, Qin Y, Guarnieri M, Garcia T, Kwei K, Mizokami M, Zhang J, Li J, Wands JR, Tong S. 2010. Impairment of hepatitis B virus virion secretion by single-amino-acid substitutions in the small envelope protein and rescue by a novel glycosylation site. J. Virol. 84:12850–12861. 10.1128/JVI.01499-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo MY, Chao M, Taylor J. 1989. Initiation of replication of the human hepatitis delta virus genome from cloned DNA: role of delta antigen. J. Virol. 63:1945–1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanchet M, Sureau C. 2006. Analysis of the cytosolic domains of the hepatitis B virus envelope proteins for their function in viral particle assembly and infectivity. J. Virol. 80:11935–11945. 10.1128/JVI.00621-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenna S, Sureau C. 1999. Mutations in the carboxyl-terminal domain of the small hepatitis B virus envelope protein impair the assembly of hepatitis delta virus particles. J. Virol. 73:3351–3358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blanchet M, Sureau C. 2007. Infectivity determinants of the hepatitis B virus pre-S domain are confined to the N-terminal 75 amino acid residues. J. Virol. 81:5841–5849. 10.1128/JVI.00096-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson DL, Paul DA, Lam J, Tribby II, Achord DT. 1984. Antigenic structure of hepatitis B surface antigen: identification of the “d” subtype determinant by chemical modification and use of monoclonal antibodies. J. Immunol. 132:920–927 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenna S, Sureau C. 1998. Effect of mutations in the small envelope protein of hepatitis B virus on assembly and secretion of hepatitis delta virus. Virology 251:176–186. 10.1006/viro.1998.9391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gripon P, Rumin S, Urban S, Le Seyec J, Glaise D, Cannie I, Guyomard C, Lucas J, Trepo C, Guguen-Guillouzo C. 2002. Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:15655–15660. 10.1073/pnas.232137699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sureau C. 2010. The use of hepatocytes to investigate HDV infection: the HDV/HepaRG model. Methods Mol. Biol. 640:463–473. 10.1007/978-1-60761-688-7_25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shearer MH, Sureau C, Dunbar B, Kennedy RC. 1998. Structural characterization of viral neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen. Mol. Immunol. 35:1149–1160. 10.1016/S0161-5890(98)00110-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paulij WP, de Wit PL, Sunnen CM, van Roosmalen MH, Petersen-van Ettekoven A, Cooreman MP, Heijtink RA. 1999. Localization of a unique hepatitis B virus epitope sheds new light on the structure of hepatitis B virus surface antigen. J. Gen. Virol. 80(Pt 8):2121–2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobotta D, Sominskaya I, Jansons J, Meisel H, Schmitt S, Heermann KH, Kaluza G, Pumpens P, Gerlich WH. 2000. Mapping of immunodominant B-cell epitopes and the human serum albumin-binding site in natural hepatitis B virus surface antigen of defined genosubtype. J. Gen. Virol. 81:369–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe T, Sorensen EM, Naito A, Schott M, Kim S, Ahlquist P. 2007. Involvement of host cellular multivesicular body functions in hepatitis B virus budding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:10205–10210. 10.1073/pnas.0704000104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abou-Jaoude G, Sureau C. 2007. Entry of hepatitis delta virus requires the conserved cysteine residues of the hepatitis B virus envelope protein antigenic loop and is blocked by inhibitors of thiol-disulfide exchange. J. Virol. 81:13057–13066. 10.1128/JVI.01495-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sureau C, Salisse J. 2013. A conformational heparan sulfate binding site essential to infectivity overlaps with the conserved hepatitis B virus A-determinant. Hepatology 57:985–994. 10.1002/hep.26125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruss V, Ganem D. 1991. The role of envelope proteins in hepatitis B virus assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:1059–1063. 10.1073/pnas.88.3.1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwei K, Tang X, Lok AS, Sureau C, Garcia T, Li J, Wands J, Tong S. 2013. Impaired virion secretion by hepatitis B virus immune escape mutants and its rescue by wild-type envelope proteins or a second-site mutation. J. Virol. 87:2352–2357. 10.1128/JVI.02701-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruss V. 1997. A short linear sequence in the pre-S domain of the large hepatitis B virus envelope protein required for virion formation. J. Virol. 71:9350–9357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu SL, Yu DM, Zhang DH, Jiang JH, Chen J, Deng L, Zhang XX. 2013. Functional analysis of hepatitis B virus immune escape mutants with insertion mutations in the surface antigen. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 21:510–513 (In Chinese.) 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2013.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raimondo G, Caccamo G, Filomia R, Pollicino T. 2013. Occult HBV infection. Semin. Immunopathol. 35:39–52. 10.1007/s00281-012-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nilsson I, von Heijne G. 2000. Glycosylation efficiency of Asn-Xaa-Thr sequons depends both on the distance from the C terminus and on the presence of a downstream transmembrane segment. J. Biol. Chem. 275:17338–17343. 10.1074/jbc.M002317200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mangold CM, Streeck RE. 1993. Mutational analysis of the cysteine residues in the hepatitis B virus small envelope protein. J. Virol. 67:4588–4597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steward MW, Partidos CD, D'Mello F, Howard CR. 1993. Specificity of antibodies reactive with hepatitis B surface antigen following immunization with synthetic peptides. Vaccine 11:1405–1414. 10.1016/0264-410X(93)90169-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]