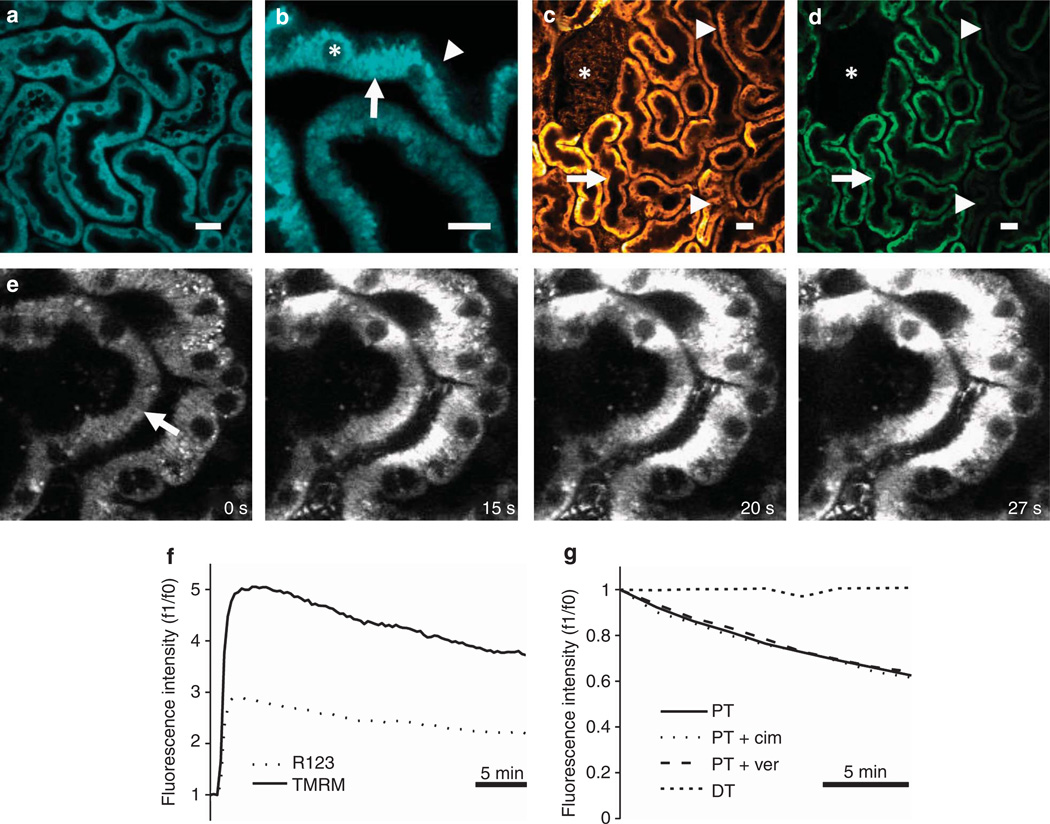

Figure 1. In vivo imaging of mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and membrane potential in the kidney.

(a, b) Mitochondrial NADH was visible at 720 nm excitation in both mouse (a) and rat (b) kidneys and showed a characteristic basolateral mitochondrial distribution in tubular cells (arrow), with very little fluorescence signal observed in non-mitochondrial structures including the apical brush border (arrowhead) or cell nuclei (asterisk). (c–g) The mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm)–dependent dyes tetramethyl rhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) and rhodamine 123 loaded into rodent kidney tubules and localized to the mitochondria; TMRM loaded well into rat proximal tubules (PTs—arrow), distal tubules (DTs—arrowheads), and glomeruli (asterisk) following intravenous injection (c), whereas rhodamine 123 loaded well into PTs (arrow), but not DTs (arrowheads) or glomeruli (asterisk) (d). Uptake of TMRM into tubules occurred initially from the basolateral side (arrow) (e); images depicted were acquired shortly after an intravenous injection of the dye into a mouse. Representative traces are depicted showing the rapid increase and subsequent slow decrease in fluorescence that occurred in rat PTs following intravenous injection of TMRM and rhodamine 123 (f). Representative traces are depicted showing that the decline of TMRM fluorescence in rat PTs was not prevented by prior intravenous injection of either cimetidine or verapamil (g); no decline in TMRM fluorescence was observed in DTs. Bars = 20 µm in (a, b) and 40 µm in (c, d).