Abstract

Background

There is a need for simple, noninvasive patient-driven disease assessment instruments in ulcerative colitis (UC). We sought to further assess and refine the previous described 6-point Mayo score.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of 282 UC patients was conducted assessing the correlation of the 2 patient-reported Mayo score components (6-point Mayo score) with the simple clinical colitis activity index (SCCAI) and a single Likert scale of patient-reported disease activity. Spearman’s correlation, sensitivity, specificity, and area under the receiver operating curves (AUC) were calculated. A separate validation study in 59 UC patients was also conducted.

Results

Participants predominantly had long-standing disease (83%) and were in self-reported remission (63%). The 6-point Mayo score correlated well with the SCCAI (rho = 0.71; P < 0.0001) and patient-reported disease activity (rho = 0.65; P < 0.0001). Using a cutpoint of 1.5, the 6-point Mayo score had 83% sensitivity and 72% specificity for patient-defined remission, and 89% sensitivity and 67% specificity for SCCAI-defined remission (score, <2.5). The 6-point Mayo score and SCCAI had similar accuracy of predicting patient-defined remission (AUC = 0.84 and 0.87, respectively). Addition of the SCCAI general well-being question to the 6-point Mayo improved the predictive ability for patient-defined remission; and a new weighted score had an AUC of 0.89 in the development cohort and 0.93 in the validation cohort. The optimal cutpoint was 1.6.

Conclusions

The patient-reported UC severity index that includes stool frequency, bleeding, and general well-being accurately measures clinical disease activity without requiring direct physician contact.

Keywords: 6-Point Mayo score, disease activity index, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index, ulcerative colitis

BACKGROUND

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic relapsing inflammatory disease of the colon. Assessment of disease severity is useful in the conduct of clinical research related to UC. Often disease activity needs to be assessed not only at study initiation but also at repeated time points throughout the study. Currently, no gold standard for disease severity assessment in UC exists. However, at least 14 disease activity indices have been developed, many of which include invasive testing, laboratory tests, and/or physician assessment that can make clinical research costly, difficult to implement, and can deter patient enrollment, especially with repeated measurements.1 Therefore, there is a need for a simple, noninvasive patient-driven disease assessment instrument.

One disease severity index that does not require physician assessment, invasive testing, or laboratory tests is the simple clinical colitis activity index (SCCAI) (Table 1).2 This index includes 6 variables: bowel frequency during the day and night, urgency of defecation, blood in the stool, general well-being, and extracolonic manifestations of UC. The SCCAI has been shown to have robust discriminative and construct validity, as well as test–retest reliability and responsiveness to change; and a score of <2.5 points has been shown to correlate with patient-defined remission.3,4 It has also been shown to correlate well with invasive indices of UC disease activity.5 Although the SCCAI is completely patient driven, it includes some variables, such as extraintestinal manifestations, that may be ambiguous to patients and thus cause incorrect patient reporting of current disease activity. Additionally, the quantity of questions in the SCCAI can make it cumbersome in studies with repeated measurements.

TABLE 1.

Components of the SCCAI, 6-Point Mayo, and Single Patient-Driven Disease Activity Question

| SCCAI Remission < 2.5 | 6-Point Mayo Remission < 1.5 |

Single Patient-Driven Disease Activity Question (Remission = Perfect or Very Good)a |

|---|---|---|

| Bowel frequency (day) | Stool frequency | “Please check what you would describe as your ulcerative colitis disease activity over the past 3 days” |

| 0 = 1–3 | 0 = Normal | Perfect (no symptoms) |

| 1 = 4–6 | 1 = 1–2 more than normal | Very good (very little symptoms) |

| 2 = 7–9 | 2 = 3–4 more than normal | Good (mild symptoms) |

| 3 = >9 | 3 = 5+ more than normal | Moderately active |

| Bowel frequency (night) | Rectal bleeding | Moderately severe |

| 1 = 1–3 | 0 = No blood seen | Severe |

| 2 = 4–6 | 1 = streaks of blood < 50% | |

| Urgency of defecation | 2 = obvious blood > 50% | |

| 1 = hurry | 3 = blood passes alone | |

| 2 = immediately | ||

| 3 = incontinence | ||

| Blood in stool | ||

| 1 = trace | ||

| 2 = occasionally frank | ||

| 3 = usually frank | ||

| General well-being | ||

| 0 = very well | ||

| 1 = slightly below par | ||

| 2 = poor | ||

| 3 = very poor | ||

| 4 = terrible | ||

| Arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, uveitis | ||

| 1 per manifestation | ||

In the validation study, “very good” was not asked.

The Mayo score is the most commonly used index in clinical trials and consists of 4 items: stool frequency, rectal bleeding, flexible sigmoidoscopic examination, and a physician global assessment (Table 1).6 A noninvasive 9-point Mayo or partial Mayo incorporates stool frequency, rectal bleeding, and the physician’s global assessment. The partial Mayo has been found to correlate closely with the full Mayo score and to independently have strong discriminative and construct validity and responsiveness to change in disease activity.4,7 However, this scoring system still requires face-to-face evaluation with a physician. Therefore, a purely patient-driven 6-point Mayo has also been infrequently used. Two previous studies have found that the 6-point Mayo correlates very well with the partial and full Mayo scores, and a cutpoint of 1.5 has been shown to correlate with patient-defined remission.7,8 However, no study has sought to correlate the 6-point Mayo score with disease severity indices outside of the Mayo scoring system. Therefore, the aim of our study was to assess the correlation of the 6-point Mayo score with the SCCAI and a single Likert scale of patient-defined disease activity (Table 1). We also sought to evaluate correlations among the 6-point Mayo, the SCCAI, and patient-defined disease activity in patients with more severe disease, defined as current or previous exposure to immunosuppressant therapy. Finally, we tested whether the discriminant ability of the 6-point Mayo could be optimized by including additional patient-reported measures included in the SCCAI. To further confirm these findings, we conducted a validation study in a separate population of UC patients with defined disease distribution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data for the initial development study were collected through mailed questionnaire. The population has been previously described.9 Briefly, the population included patients at least 18 years old with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) coded diagnosis for UC (556.0–556.6 and 556.8–556.9), no concomitant ICD-9 code for Crohn’s disease (555.0–555.2, 555.9), and an outpatient gastroenterology clinic visit within the past 24 months. The survey included 2 separate questions asking participants if they had UC. To be included in this study, participants had to answer both questions in the affirmative and have no missing data for any of the disease severity questions that are described below.

The survey instrument included all aspects of the SCCAI and the 6-point Mayo score. Illustrations and descriptions aimed at a 6th-grade reading level were used to illustrate the extra-intestinal manifestation questions in the SCCAI and to limit patient confusion or the lack of understanding of the medical terminology in the index. Furthermore, we included a single patient-driven disease activity question that read, “Please check what you would describe as your ulcerative colitis activity over the past 3 days.” There were 6 possible responses to this question ranging from perfect (no symptoms) to severe (Table 1).

The validation study used the same SCCAI and 6-point Mayo indices questions (including the illustrations and descriptions) and the single patient-driven disease activity question used in the initial study. This study was administered to consecutively enrolled clinic patients in a separate prospective cohort study at the University of Pennsylvania (IBD Immunology Initiative or I3 study). All patients were at least 18 years old with an ICD-9 code for UC (556.0–556.6 and 556.8–556.9) confirmed by a gastroenterologist and verified by review of the patient’s electronic medical record. Review of the patient’s electronic medical record also served to confirm disease extent (left-sided colitis versus extensive colitis).

Continuous variables are reported as medians with ranges or as means with standard deviations, and categorical variables as counts and proportions. Correlations were measured using Spearman’s correlation coefficients (rho). To assess sensitivity and specificity for the SCCAI and the 6-point Mayo, we used the patient-driven disease activity question as the gold standard. Clinical remission was defined as a self-assessment of perfect or very good (minimal disease activity). Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated, and area under the ROC curves (AUC) for different disease indices were computed. Logistic regression modeling and chi-square tests were used to compare AUC from different ROC curves. Logstic regression was also used to determine beta coefficients for index components, which in turn were used as weights to compute a total index score. Optimal cutpoints were identified giving equal preference for sensitivity and specificity. Each possible cutpoint was categorized by the lowest value of sensitivity or specificity (min_spec_sen). The optimal cutpoint was that with the maximum min_spec_sen. This approach provided similar results to analyses using the maximum product of sensitivity and specificity (data not shown except where important differences were identified). SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and STATA (Stata, Corp, College Station, TX) were used for data management and analysis. The study design was approved by the Institution Review Boards at both the University of Pennsylvania and the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center.

RESULTS

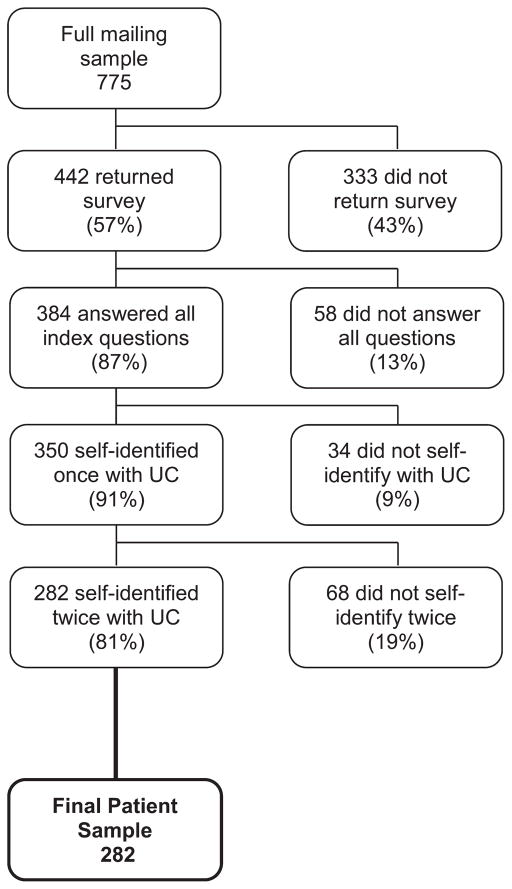

The survey for the development phase of the study was mailed to 775 UC patients, and responses were received from 442 patients (57% response rate). We had limited information on nonresponders, but men were less likely to respond (data not shown). After applying the exclusion criteria, 282 participants were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). The majority of respondents had long-standing disease that was in clinical remission, although approximately one third of the respondents were currently on some form of immunosuppressant therapy (including thiopurine, cyclosporine, methotrexate, or anti-tumor necrosis factor [TNF] therapies) and an additional 20% had previous exposure to immunosuppressant therapy for their UC (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Identification of initial study patient population.

TABLE 2.

Summary of Patient Characteristics in Initial Cohort and Validation Study Cohorta

| Characteristic | Initial Cohort (n = 282) | Validation Cohort (n = 59) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 167 (59) | 33 (56) |

| Male | 115 (41) | 26 (44) |

| Age, yr | ||

| Median (interquartile range) | 45 (34–59) | 38 (27–51) |

| Mean (standard deviation) | 47 (16) | 39 (14) |

| Site, n (%) | ||

| Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center | 27 (10) | |

| Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania | 255 (90) | 59 (100) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 251 (91) | 52 (88) |

| African American | 12 (4) | 4 (7) |

| Asian | 4 (1) | 3 (5) |

| Other | 8 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||

| Current smoker | 13 (5) | N/A |

| Past smoker | 100 (38) | — |

| Never smoked | 157 (58) | — |

| Length of time with UC (yr), n (%) | ||

| <1 | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| 1–5 | 47 (17) | 9 (15) |

| 5–10 | 76 (28) | 18 (31) |

| ≥10 | 152 (55) | 32 (54) |

| When last active UC symptoms were experienced, n (%) | ||

| Currently or within past 3 mo | 98 (37) | N/A |

| 3–6 mo ago | 27 (10) | |

| 6 mo to 1 yr ago | 30 (11) | |

| >1 yr ago | 113 (42) | |

| 5-ASA (oral and/or rectal) | ||

| Current use | 168 (60) | 39 (66) |

| Past use | 104 (37) | 16 (27) |

| Corticosteroids (oral and/or rectal) | ||

| Current use | 32 (11) | 7 (12) |

| Past use | 173 (61) | 35 (59) |

| Azathioprine/6-MP | ||

| Current use | 52 (18) | 19 (32) |

| Past use | 74 (26) | 13 (22) |

| Cyclosporine and/or tacrolimus | ||

| Current use | 7 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Past use | 4 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Methotrexate | ||

| Current use | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Past use | 8 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Anti-TNF therapies (infiiximab, adalimumab, certolizumab) | ||

| Current use | 40 (14) | 16 (27) |

| Past use | 46 (16) | 7 (12) |

| Current immunosuppressant use (azathioprine, 6-MP, cyclosporine, tacrolimus methotrexate, anti-TNF) | 91 (32) | 33 (56) |

| Past immunosuppressant use (azathioprine, 6-MP, cyclosporine, tacrolimus methotrexate, anti-TNF) | 61 (22) | 18 (31) |

Missing data excluded for each category.

5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; 6-MP, 6-mercatopurine; N/A, not applicable.

SCCAI, 6-Point Mayo, and Patient Assessment of Disease Activity

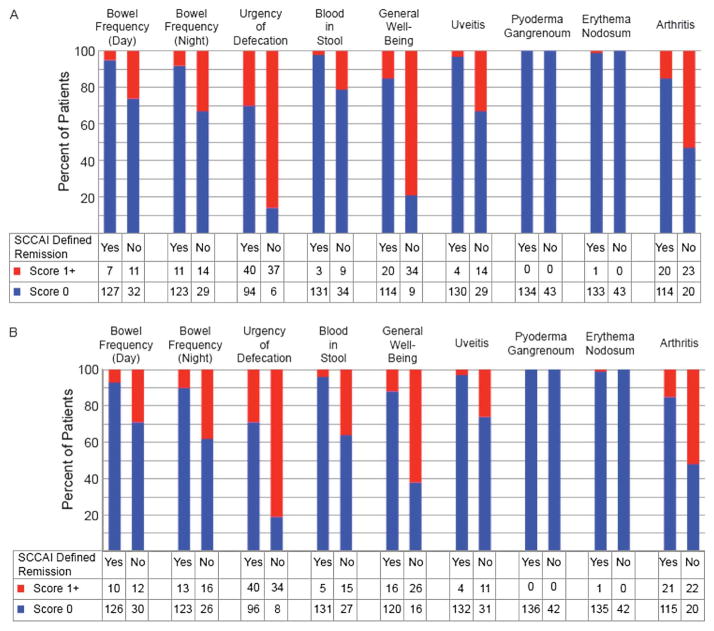

Sixty-three percent of the surveyed population were in a remission status defined by the 6-point Mayo or patient-driven activity question (Table 3). Notably, however, only 53% were in a remission status defined by the SCCAI. Similar results were found among the 152 patients who had previous or current exposure to immunosuppressant medications. Therefore, additional analysis was conducted to explore why remission rates were lower with the SCCAI than with the 6-point Mayo (Fig. 2A) or patient-driven disease activity (Fig. 2B). In patients in a remission status defined by the 6-point Mayo score, 3 SCCAI questions appeared to be primarily responsible for the discrepancy between the 6-point Mayo and the SCCAI, with more than 50% of those with active disease (as defined by the SCCAI) answering in the affirmative to the questions: urgency, decreased general well-being, and presence/absence of arthritis (Fig. 2A). Similar results were seen when using the patient-driven disease activity question to define remission (Fig. 2B).

TABLE 3.

Disease Severity Indices

| Mean Score | Median Score | Minimum Score | Maximum Score | Percent in Remission | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full survey population (n = 282) | |||||

| SCCAI | 2.8 | 2 | 0 | 16 | 53% (score < 2.5) |

| 6-point Mayo | 1.3 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 63% (score < 1.5) |

| Patient-driven question | 2.2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 63% (score 1 or 2) |

| Exposure (current and past) to immunosuppressant therapy (azathioprine, 6-mercatopurine, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, methotrexate, anti-TNFs) (n = 152) | |||||

| SCCAI | 3 | 3 | 0 | 16 | 49% (score < 2.5) |

| 6-point Mayo | 1.4 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 59% (score < 1.5) |

| Patient-driven index | 2.3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 59% (score 1 or 2) |

| Validation population (n = 59) | |||||

| SCCAI | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0 | 12 | 68% (score < 2.5) |

| 6-point Mayo | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0 | 6 | 71% (score < 1.5) |

| Patient-driven index | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1 | 4 | 69% (score 1 or 2) |

| Pancolitis validation population (n = 45) | |||||

| SCCAI | 2.7 | 2.0 | 0 | 12 | 62% (score < 2.5) |

| 6-point Mayo | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0 | 6 | 67% (score < 1.5) |

| Patient-driven index | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1 | 4 | 64% (score 1 or 2) |

| Left-sided validation population (n = 14) | |||||

| SCCAI | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0 | 11 | 86% (score < 2.5) |

| 6-point Mayo | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0 | 5 | 86% (score < 1.5) |

| Patient-driven index | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1 | 4 | 86% (score 1 or 2) |

FIGURE 2.

A, Evaluation of patients in a 6-point Mayo remission. B, Evaluation of patients in remission as defined by a single Likert scale of patient-defined disease activity. The lower panels divide patients by their SCCAI remission status and shows breakdown of responses to individual components of the SCCAI.

Correlation of Patient-driven Disease Assessment, SCCAI, and 6-Point Mayo

In the overall population, the 6-point Mayo score strongly correlated with the SCCAI and the patient-driven disease activity question; the SCCAI also strongly correlated with the patient-driven disease activity question (Table 4). When examining those patients with current or past immunosuppressant exposure, the correlations were similarly strong (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Correlations Between SCCAI, 6-Point Mayo, and Patient-Driven Assessment

| Indices | Rho; P | Sensitivity; Specificity (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| Full survey population (n = 282) | ||

| 6-point Mayo and SCCAI | 0.71; <0.0001 | 89; 67 |

| 6-point Mayo and patient-driven assessment | 0.65; <0.0001 | 83; 72 |

| SCCAI and patient-driven assessment | 0.66; <0.0001 | 76; 87 |

| Exposure to immunosuppressant therapy (n = 152) | ||

| 6-point Mayo and SCCAI | 0.73; <0.0001 | 91; 71 |

| 6-point Mayo and patient-driven assessment | 0.67; <0.0001 | 82; 73 |

| SCCAI and patient-driven assessment | 0.66; <0.0001 | 73; 86 |

| Validation cohort (n = 59) | ||

| 6-point Mayo and SCCAI | 0.74; <0.0001 | 95; 79 |

| 6-point Mayo and patient-driven assessment | 0.63; <0.0001 | 90; 72 |

| SCCAI and patient-driven assessment | 0.74; <0.0001 | 85; 72 |

| Pan-colitis cohort (n = 45) | ||

| 6-point Mayo and SCCAI | 0.76; <0.0001 | — |

| 6-point Mayo and patient-driven assessment | 0.60; <0.0001 | — |

| SCCAI and patient-driven assessment | 0.71; <0.0001 | — |

| Left-sided colitis cohort (n = 14) | ||

| 6-point Mayo and SCCAI | 0.64; 0.01 | — |

| 6-point Mayo and patient-driven assessment | 0.65; 0.01 | — |

| SCCAI and patient-driven assessment | 0.66; 0.01 | — |

Calculated using 6-point Mayo remission <1.5 and SCCAI remission <2.5.

Sensitivity, Specificity, and ROC Curves to Identify Patient-defined Remission

In our population, the optimal cutpoint for the 6-point Mayo was marginally different between the maximum lowest value of sensitivity and specificity (cutpoint, <1.5) and the maximum product of sensitivity and specificity (cutpoint, <0.5) (data not shown). Using a cutpoint of 1.5, the 6-point Mayo remission score had good sensitivity and specificity for patient-defined remission and for SCCAI remission (defined as a score < 2.5); the SCCAI had similarly strong sensitivity and specificity for patient-defined remission (Table 4). In patients with current or past immunosuppressant therapy exposure, similar results were found (Table 4).

We defined remission using a single patient-driven disease activity question as perfect or very good under the assumption that patients would be unlikely to seek additional therapy if they considered themselves to have very good control of their disease. However, we repeated the assessment of the sensitivity and specificity of the 6-point Mayo and SCCAI defining remission as only those who answered their disease activity as “perfect.” Using the same cutpoint, this resulted in a lower specificity for both scoring systems: 6-point Mayo, sensitivity 89% and specificity 50%; SCCAI, sensitivity 83% and specificity 61%.

In the full population, the SCCAI AUC for predicting patient-defined remission was 0.87; the 6-point Mayo AUC was 0.84. In patients exposed to immunosuppressant therapy, the ROC curves showed a similar nearly-equivalent area under the curve for SCCAI and the 6-point Mayo with an area under the curve of 0.86 and 0.85, respectively.

Additional analysis was conducted to evaluate if adding any of the SCCAI components (using their original SCCAI scaling) to the 6-point Mayo improved the accuracy of predicting patient-defined disease remission (Table 5). Two of the SCCAI components, urgency and general well-being, significantly increased the AUC when added to the 6-point Mayo score (P = 0.01 and P = 0.0001, respectively). When both components were added to the 6-point Mayo score, the resulting AUC was 0.90, which was significantly greater than the area under the curve for the 6-point Mayo score alone (P < 0.0001). Sequential addition of both urgency and general well-being was also performed: the addition of the SCCAI general well-being to the 6-point Mayo already containing the SCCAI urgency question resulted in a significant improvement in AUC (0.87 versus 0.90; P = 0.0014); however, the addition of the SCCAI urgency to the 6-point Mayo already containing the SCCAI general well-being did not reach statistical significance (0.89 versus 0.90; P = 0.17). Analysis limited to those patients exposed to immunosuppressant therapy produced similar findings (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Comparison of AUC Generated by the Addition of SCCAI Components to the 6-Point Mayo Predicting Patient-Defined Remission

| AUC | P (Chi Square) | AUC | P (Chi Square) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full initial development survey population (n = 282) | Validation survey population (n = 59) | |||

| 6-point Mayo score (base model) | 0.84 | — | 0.86 | — |

| SCCAI component added | ||||

| During the day | 0.85 | 0.37 | 0.88 | 0.42 |

| Bowel frequency during the night | 0.85 | 0.44 | 0.86 | 0.51 |

| Urgency of defecation | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.86 | 0.95 |

| Blood in the stool | 0.84 | 0.50 | 0.86 | 0.94 |

| General well-being | 0.89 | 0.0001 | 0.91 | 0.13 |

| Uveitis | 0.85 | 0.65 | 0.86 | 0.37 |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | N/Aa | N/Aa | N/Aa | N/Aa |

| Erythema nodosum | 0.84 | 0.32 | N/Aa | N/Aa |

| Arthritis | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.37 |

| Sum of all extra-intestinal manifestations | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.37 |

| 6-point Mayo plus SCCAI urgency and general well-being | 0.90 | <0.0001 | 0.90 | 0.24 |

| Exposure to immunosuppressant therapy (n = 152) | ||||

| 6-point Mayo score (base model) | 0.85 | — | ||

| SCCAI component added | ||||

| Bowel frequency during the day | 0.86 | 0.43 | ||

| Bowel frequency during the night | 0.85 | 0.97 | ||

| Urgency of defecation | 0.88 | 0.03 | ||

| Blood in the stool | 0.85 | 0.64 | ||

| General well-being | 0.88 | 0.04 | ||

| Uveitis | 0.86 | 0.60 | ||

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | N/Aa | N/Aa | ||

| Erythema nodosum | N/Aa | N/Aa | ||

| Arthritis | 0.84 | 0.24 | ||

| Sum of all extra-intestinal manifestations | 0.84 | 0.36 | ||

| 6-point Mayo plus SCCAI urgency and general well-being | 0.89 | 0.02 | ||

Unable to calculate due to insufficient numbers of patients reporting these conditions. Bold values have a P value <0.05.

Sensitivity and Specificity to Identify Remission with Well-being, Urgency, Bleeding, and Stool Frequency

Based on these findings, analysis was conducted in the full cohort to determine optimal cutpoint for a combined 6-point Mayo score with the SCCAI components of general well-being, hereafter referred to as the patient-reported UC severity index (PRUCSI). Using the same ordinal levels of the Mayo and SCCAI questions, a new weighted score was determined (Table 6): (0.7824 × Mayo stool frequency) + (1.0925 × Mayo rectal bleeding) + (1.4727 × SCCAI general well-being). The optimal cut-point was 1.6 (sensitivity, 83% and specificity, 80%).

TABLE 6.

Patient-Reported UC Severity Index

| AUC | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Using new calculated weightsa | |||

| Development population | 0.89 | 83 | 80 |

| Validation population | 0.93 | 83 | 83 |

| Using traditional weightsb | |||

| Development population | 0.89 | 78 | 84 |

| Validation population | 0.91 | 81 | 83 |

New weighted score = (0.7824 × Mayo stool frequency) + (1.0925 × Mayo rectal bleeding) + (1.4727 × SCCAI general well-being); remission < 1.6.

Traditional weighted score = (Mayo stool frequency) + (Mayo rectal bleeding) + SCCAI general well-being; remission < 1.5.

Validation Study

In the prospective validation cohort, 45 patients had physician-identified pancolitis and 14 patients had left-sided colitis. Baseline demographics of these 59 patients were not significantly different from the initial study population; however, a larger percentage of the validation population was currently on immunosuppressant therapy (Table 2).

SCCAI, 6-Point Mayo, and Patient Assessment of Disease Activity

The results of the disease severity assessments for the validation survey population are shown in Table 3. The percentage of patients in the total validation population in remission was comparable by any of the 3 disease activity measurements; however, when comparing patients with pancolitis versus left-sided colitis, a greater percentage of patients with left-sided colitis were in remission.

Correlation of Patient-driven Assessment, SCCAI, and 6-Point Mayo

In the validation population, the 6-point Mayo again strongly correlated with the SCCAI and the patient-driven disease activity question (Table 4). A significant correlation was also seen with the SCCAI and the single patient-driven disease activity question (rho = 0.74; P < 0.0001). When examining pancolitis and left-sided colitis subsets of the validation study, the correlations were similarly strong (Table 4).

Sensitivity, Specificity, and ROC Curves to Identify Patient-defined Remission

Similar analysis was carried out in our validation study. The SCCAI area under the curve was 0.90, and the 6-point Mayo area under the curve was 0.86. As in the development phase, the greatest improvement in the AUC was with the addition of general well-being (AUC = 0.91; P = 0.13) (Table 5). In the validation cohort, using a cutpoint of 1.6 for remission, the sensitivity and specificity were both 83% for the PRUCSI, similar to that seen in the development phase (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have drawn from 2 widely used disease activity indices to develop an efficient noninvasive measure of UC disease activity. The 6-point Mayo score correlated strongly with the SCCAI and patient-reported disease activity, had a similar sensitivity and specificity as the SCCAI for patient-reported remission, and performed equally well in patients with more advanced disease (as defined by immunosuppressant drug exposure) and those with varying UC disease extent (left-sided colitis versus pancolitis). Previous studies have shown that the 6-point Mayo score correlates well with patient-driven disease activity and both the partial and full Mayo scores.7,8 Our study is the first to correlate and validate the 6-point Mayo with disease activity indices outside of the Mayo scoring system and in patients on immunosuppression and those with varying extent of UC. Furthermore, the 6-point Mayo score avoided the use of cumbersome and potentially confusing questions regarding extraintestinal manifestations of the inflammatory bowel disease and thus represents a simple, efficient, and effective noninvasive disease severity measurement. However, we have also shown that the addition of a single question from the SCCAI regarding general well-being improves the discriminative ability of the 6-point Mayo score for patient-defined disease activity with minimal additional burden to patients or researchers. The optimal cutpoint of this new disease activity measure (PRUCSI) to distinguish patient-defined remission from active disease is 1.6.

Inclusion of symptoms of urgency and general well-being led to discrepancies between an SCCAI-defined remission and our 2 other definitions of remission. Urgency is typically a symptom of rectal inflammation, but it can also be a symptom of irritable bowel syndrome. Likewise, general well-being can be affected by many factors outside of UC disease activity. Based on the sequential assessment in both the overall and validation cohorts, the addition of general well-being seemed to be a sufficient improvement to the 6-point Mayo in predicting patient-defined remission. Given increased interest by regulatory agencies to capture patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials, PRUCSI may be preferred to the 6-point version.

The extraintestinal manifestation questions in the SCCAI, specifically arthritis and uveitis, also led to discrepancies between SCCAI-defined remission and patient-defined remission in the initial study. However, the addition of these questions to the 6-point Mayo index did not seem to improve the test-operating characteristics. This is likely because patients mistake noninflammatory bowel disease–related symptoms such as osteoarthritis or allergic conjunctivitis for these extraintestinal manifestations of UC.

In our validation study, we did not find the high reported rates of extraintestinal manifestations that we saw in our initial study. This may be the result of differences in the study populations themselves: although the initial development study was a mailed questionnaire, completed entirely by the patient outside of the clinical setting, the validation study was collected in the clinical setting and during enrollment within a larger prospective study. Unmeasured differences (recent exposure to a physician, willingness to enroll in a clinical study, etc) may have contributed to these variations, and stress the need for a simple, unambiguous, patient-driven disease activity index.

The new weights determined in the development of the PRUCSI led to slightly higher discriminant ability, sensitivity, and specificity for patient-defined remission in both our developmental and validation cohorts, although slightly lower specificity in the developmental cohort. However, for those more familiar with the original 6-point Mayo and SCCAI, it is worth noting that the use of original weights led to similar findings (Table 6) and may facilitate the ease of using this combined score in existing clinical practice.

There are potential limitations to our study. The indices examined in this study were for clinical remission, specifically patient-defined remission, only. Endoscopic and histologic disease activity measures have been correlated with important outcomes, including colectomy, colorectal cancer, and quality of life.1,10–13 However, in many studies, invasive disease assessment may be infeasible or serve as a deterrent to patient enrollment. Even in studies that use invasive disease assessment methods, more frequent follow-up measurements may be more easily obtained through mail, e-mail, or phone, without direct physician contact. Furthermore, patient-perceived assessment of disease activity is arguably paramount in assessing the quality of life. In these settings, the utility of a simple patient-driven disease assessment tool can be appealing to researchers and patients alike but would not be expected to completely eliminate the need for lower endoscopy if the assessment of bowel inflammation is an important study question.

In the development of PRUCSI, we asked patients to characterize their bleeding, stool frequency, urgency, and general well-being using the existing ordinal components of the 6-point Mayo and SCCAI. In future studies, it would be useful to measure these variables more precisely to determine whether the existing ordinal categories are optimized for identifying patient-defined remission. It is possible that such information may recategorize the stool frequency, rectal bleeding, or general well-being components by providing different descriptors or weights for these variables that could lead to even better test-operating characteristics.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the 6-point Mayo score, composed of only 2 questions regarding stool frequency and the presence of blood, well correlated with the SCCAI and performed comparably to the SCCAI in identifying patient-perceived clinical remission. We have further shown that the addition of the SCCAI general well-being increased the predictive value of the 6-point Mayo and validated these findings in a separate UC population with varying disease extent. This 3-question assessment of bleeding, stool frequency, and general well-being represents a simple and reproducible patient-driven UC disease severity index for use in observational studies or in clinical trials without direct physician assessment.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a research grant from Centocor and the National Institutes of Health (K08 DK084347-01, R25-DK066028, and K24 DK078228). C. E. Sokach has received a research grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH R25 DK066028). C. A. Siegel has received payment for lectures from Janssen, Abbvie, and Merck. J. D. Lewis has received consultancy fee from Amgen. M. Bewtra has received payment for lectures from Imedex.

Footnotes

The authors have no confiicts of interest to disclose.

Author contributions: Study concept and design, patient recruitment, data interpretation and statistical analysis, drafting of manuscript, and critical revision of manuscript: M. Bewtra. Data interpretation and statistical analysis and critical revision of manuscript: C. M. Brensinger. Data interpretation and critical revision of manuscript: V. T. Tomov. Patient recruitment, data entry, data interpretation, and critical revision of manuscript: T. B. Hoang. Patient recruitment, data entry, data interpretation, and critical revision of manuscript: C. E. Sokach. Patient recruitment and critical revision of manuscript: C. A. Siegel. Study concept and design, data interpretation, and critical revision of manuscript: J. D. Lewis.

References

- 1.D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:763–786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, et al. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins PD, Schwartz M, Mapili J, et al. Patient defined dichotomous end points for remission and clinical improvement in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2005;54:782–788. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.056358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner D, Seow CH, Greenberg GR, et al. A systematic prospective comparison of noninvasive disease activity indices in ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1081–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins PD, Schwartz M, Mapili J, et al. Is endoscopy necessary for the measurement of disease activity in ulcerative colitis? Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:355–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhanda AD, Creed TJ, Greenwood R, et al. Can endoscopy be avoided in the assessment of ulcerative colitis in clinical trials? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2056–2062. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis JD, Chuai S, Nessel L, et al. Use of the noninvasive components of the Mayo score to assess clinical response in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1660–1666. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bewtra M, Kilambi V, Fairchild AO, et al. Patient preferences for surgical versus medical therapy for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:103–114. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000437498.14804.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Froslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, et al. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zahn A, Hinz U, Karner M, et al. Health-related quality of life correlates with clinical and endoscopic activity indexes but not with demographic features in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:1058–1067. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000234134.35713.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutter M, Saunders B, Wilkinson K, et al. Severity of inflammation is a risk factor for colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:451–459. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, et al. Cancer surveillance in longstanding ulcerative colitis: endoscopic appearances help predict cancer risk. Gut. 2004;53:1813–1816. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.038505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]