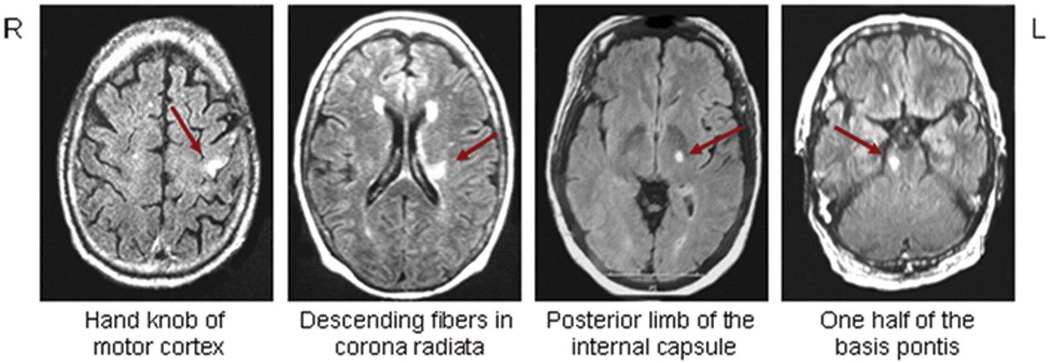

Figure 1.

Effects of damage to the corticospinal system on movement generation and feed-forward computations. A. In the intact system, the motor command for elbow flexion, for example, computed in the motor areas is sent to the spinal cord motorneurons (MN) and interneurons (red line). The command results in agonist contraction (biceps), antagonist relaxation (triceps), and the generation of force. A copy of the motor command is input to an internal model of limb position computed centrally (for details, see Frey et al., this volume). B. After damage to the corticospinal system, the generation of movement is compromised both by reduced descending commands to the spinal cord (dotted red line) and by interference with feed-forward computations of the internal model. Some descending effects illustrated here are: reduced spinal MN (and muscle motor units) activation, decreased agonist drive, increased co-activation of antagonist muscles, and altered sensory input due to loss of supraspinal inhibition of sensory afferents. As a consequence, activation and termination of muscle activity are delayed, force production and its rate are decreased, and muscle activation is less selective. Movements are slower and less accurate, leading to repeated attempts or compensatory strategies and, overall, less functionality. Centrally, compensatory increase in movement plans (or effort), and irregular sensory feedback and proprioception may lead to the formation of an abnormal internal model and erroneous feed-forward computations.