Abstract

Plant propagation is critical to augment the resource and has been the main concern for farmers and planters through history. India has evolved the science of Vṛkṣāyurveda to address the above issue. An effort is made here to review Vṛkṣāyurveda literature related to nursery techniques. Different libraries were visited and relevant review material obtained by hand search and from databases. Interaction with Sanskrit scholars and eminent scientists working in the field of Vṛkṣāyurveda, as well as the efforts of the authors of this paper, helped in the selection of pertinent literature. In the absence of original texts, authentic translations of the publications were referred. A conscious decision was made to limit the search to the fields of seed storage, pretreatment and nutrition of seedlings. To have a comparative account recent trends and literature on nursery technology were also examined. This was supplemented by interviews with traditional organic farmers. Our survey revealed that the time period of the literature pertaining to Vṛkṣāyurveda ranges from BCE 1200 to the present times. The subject has evolved from morphological descriptions and uses of plants, in texts such as Ṛgveda and Atharvaveda, to treatises dedicated solely to the art of growing plants like Kṛṣi-Parāśara and Vṛkṣāyurveda. It is also evident that there were important periods when more works appeared across subjects such as water divining, soil types, seed collection and storage, propagation, germination and sprouting, watering regimen, pest, and disease control. The review revealed that valuable information pertaining to nursery techniques is available in Vṛkṣāyurveda, which can be used in the development of nursery protocol. This will not only help in effective organic nursery management, but also ensure the health and livelihood security of the communities involved and effective waste management.

KEY WORDS: Nursery technique, seedlings, traditional agriculture, Vṛkṣāyurveda

INTRODUCTION

Āyurveda, a science which is based on the “Pancamahābhūta” and “Tridoṣa” theories, is as much applicable to plants and animals as it is to human beings. While the use of Βyurveda for mankind is increasing in popularity, especially in the recent times, its use for animals and plants is not yet popular and widespread. The branches, respectively known as Mṛgāyurveda and Vṛkṣāyurveda, however, have been in practice in ancient times.

Vṛkṣāyurveda is that branch of science which deals with growing healthy plants to obtain desired fruits, flowers, grains, etc., from them.[1] In general, the term is used to denote knowledge of plant life, in all aspects.[2] Ever since farming has been practiced by man, plant characters such as healthy, disease free, vigorous and phenotypically superior seedlings, with no physical damage and having good viability, have been the basis of agriculture. Toward this end, various practices have been incorporated into the process of selection of mother plants and diaspore, storage of diaspore, treatment of land and diaspore, before sowing, and also after sowing. All these practices, over time, have led to standard propagation protocols being developed. From time to time these protocols have been improved, based on aspects such as the ability to produce better crops (both with respect to quantity and quality), early maturity, increase in vigor of seedlings, their ability to withstand the shock of transplantation, disease and pest resistance, enhancing the viability of seeds and breaking dormancy, by adopting inputs from newer technologies. Post World War II, traditional practices have been more or less replaced by so-called modern techniques, which are dependent on chemicals for disease free and vigorous plants.

Conventional nursery techniques adopt chemical inputs at various stages, such as storage, preparation of mother beds, increase in germination percentage, better growth, disease and pest control, better yield, etc., for the production of seedlings.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] However, none of these methodologies apply traditional techniques for seedling production. Today, it is becoming evident that whereas chemical inputs show dramatic short-term benefits, in the longer run they adversely impact the soil, water and perhaps the nutritional quality of the plants.[20] Thus, it is evident that there is great scope to integrate traditional practices for better productivity of quality planting materials.

The present paper looks at the current status of research and recent trends in the field of Vṛkṣāyurveda related to organic production of nursery seedlings based on intensive literature survey. It also gives an overview of the different processes documented in the ancient texts for growing plants.

EVOLUTION OF VṚKṢĀYURVEDA LITERATURE

A review of literature from various sources, including books and journals in the libraries at the Institute of Trans-disciplinary Health Science and Technology, Bangalore, Center for Indian Knowledge Systems (CIKS), Chennai and Kerala Forest Research Institute, Thrissur and personal collection of published literature from various sources, was carried out. It was observed that the earliest work giving details related to this topic was the Ṛgveda, which was presumably brought out between BCE 1500 and BCE 1200.[21] With regard to publications pertaining to Vṛkṣāyurveda, it was observed that although the term “Vṛkṣāyurveda” was mentioned for the first time in Kautilya's Arthaśāstra, details regarding use of plants or plant parts as medicine, their properties, their morphological descriptions, etc., have been mentioned in ancient texts such as the Ṛgveda, Atharvaveda, Caraka Saṃhitā and Suśruta Saṃhitā, Mahābhārata, etc.[1] Later texts like Bruhat Saṃhitā and Agnipurāṇa had separate chapters dedicated to Vṛkṣāyurveda. Treatises such as Kṛṣi-Parāśara, Kaśyapīyakṛṣisūkti, Mānasollāsa, Vṛkṣāyurveda and Lokopakāra were dedicated to the art of growing plants for use and pleasure. From the early 18th century to the mid-20th century not many works relating to traditional plant science were written. Following this, when the benefits of traditional agricultural practices were rediscovered, there appeared a spurt in the number of publications pertaining to Vṛkṣāyurveda, which were mainly English translations. Some of the recent publications such as Testing and Validation of Indigenous Knowledge – the COMPAS experience from Southern India,[22] Use of Animal Products in Traditional Agriculture,[23] Knowledge and Belief Systems in the Indian subcontinent,[24] Modern Dilemmas and Traditional Insights,[25] Ancient and Medieval History of Indian Agriculture,[26] Agricultural Heritage of India,[27] Bridging gap between Ancient and Modern Technologies to Increase Agricultural Productivity,[28] A Textbook on Ancient History of Indian Agriculture[29] and a chapter “Agriculture” in the book A Concise History of Science in India[30] as well as articles such as organic production of medicinal, aromatic and dye-yielding plants (an ecoport)[31] have attempted to understand traditional systems of agriculture and their applicability in modern times. The Inventory of Indigenous Technical Knowledge in Agriculture (Documents 1-5) documents the indigenous traditional knowledge of India in agriculture.[32]

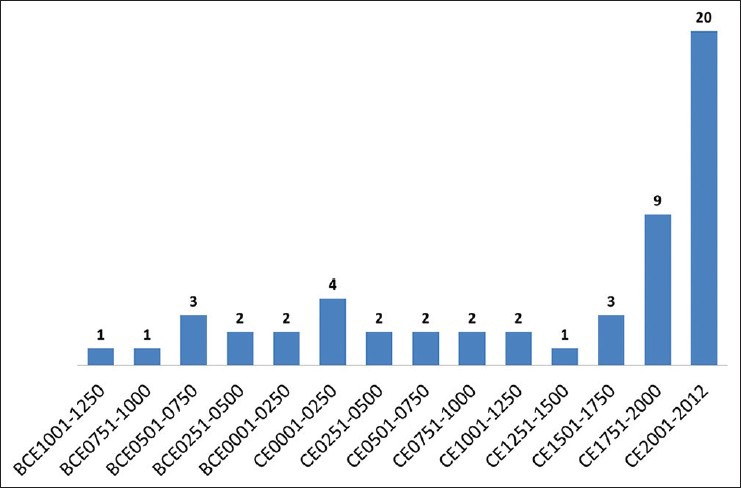

Although the earlier literary works were in Sanskrit, Pali, Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada, etc., the later works were translations of the earlier texts. Figure 1 gives a summary of progress through history on the interest shown in Vṛkṣāyurveda, evident through the number of publications on this topic.

Figure 1.

Graph showing publications on Vrikshayurveda

A survey of local farmers’ practices was also done by conducting interviews with organic farmers practicing traditional agriculture. These visits helped to obtain first-hand information on the methodologies followed by them for storage, pretreatment, and nutrition and pest/disease management. Procedures for preparation of various decoctions were also referred. Furthermore, newsletters like honey bee, which documents traditional farmers’ practices, were reviewed.

INFORMATION RELATING TO VARIOUS FACETS OF VṚKṢĀYURVEDA IN PAST LITERATURE

From the review of literary works, it is clear that methodologies involving simple as well as complicated procedures were being practiced by the farmers in the ancient times. Topics such as origin of life, ecology, distribution of forests, morphology of plants, histology and physiology, natural indicators for ground water, construction of water reservoirs, classification of plants, types of soils, procedures to be followed for collection and storage of seeds, sowing procedures, right season/best days for sowing, rituals to be followed during sowing/planting, pretreatment of seeds to ensure good germination, treatment for quick sprouting, preparation of bed, pit, etc., before sowing; plant distances for different types of plants, watering regimen, general nourishment processes to be followed and special nourishment procedures for fruiting and flowering plants, vegetative propagation process, types of ailments, treatments for diseases and pests, methods to produce specialized plants (horticultural wonders), methods to produce trees with beautiful flowers and tasty fruits, methods to produce trees bearing seedless fruits, Indian agricultural implements etc., have been dealt with in detail in these texts.[33,34,35,36,37,38] More recent publications have looked at the effect of paρcagavya and kuṇapajala on plant growth.[39,40,41,42,43]

With respect to storage and pretreatment of diaspore and nutrition of seedlings, the following observations were made:

Diaspore is any agent that is used in dispersal of the species from which a new individual may develop. In most of the higher plants, seeds are these agents; vegetative parts such as leaf, stem, and root may also function as diaspore in many species.

STORAGE OF DIASPORE

Many simple as well as complicated procedures have been described in these texts [Table 1].[23,34,37,38,44,45,46,47] Use of powders of Solanum indicum, Sesamum indicum, Embelia ribes and Brassica juncea, milk, ghee# and cow dung has been mentioned in almost all the texts for protection during storage. Use of sunlight for drying the seeds was another common feature in all the texts. Mention has also been made of the importance of collecting seeds from naturally ripened or mature fruits. Texts like Kṛṣi-Parāśara have stated the importance of the right season for collection of seeds and also removing impurities such as chaff and adulterant seeds. This text also says that seeds have to be kept away from damaging agents such as leftover food, animals, fire, lamp, buttermilk, salt, etc., and also from a woman who has just given birth, a menstruating woman and a barren woman.

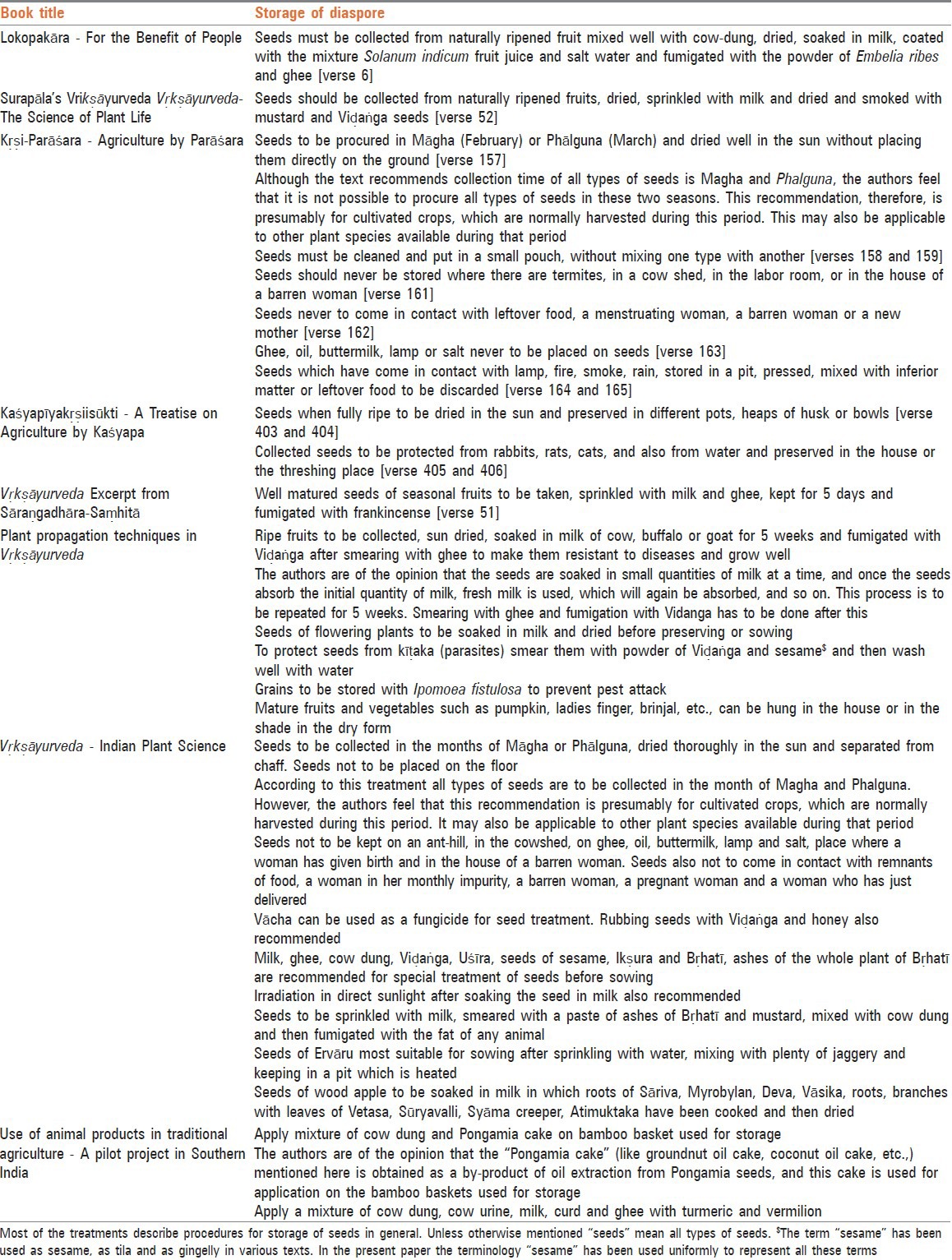

Table 1.

Summary of procedures for storage treatment mentioned in some important Vṛkṣāyurveda texts

# The term “ghee” and “clarified butter” are used to denote ghee in the various Vṛkṣāyurveda texts. In the present paper "ghee" has been used to represent both these terms.

PRETREATMENT OF DIASPORE

Methods for pretreatment of seed and vegetative propagules have also been detailed in the texts [Table 2].[35,37,38,44,46,47,48] These include smearing with ash of Sesamum indicum and Solanum indicum, smearing with Alangium salviifolium oil, fumigating with fat of some animal, Solanum indicum seeds, E. ribes, ghee or turmeric, soaking in water mixed with fat, marrow or meat of animals and treatment with meat. As with treatments for storage, pretreatments for good germination also make use of cow dung and milk of cow, sheep, goat, etc., and include smearing or rubbing the seeds (with cow dung) and sprinkling or soaking the seeds (in milk).

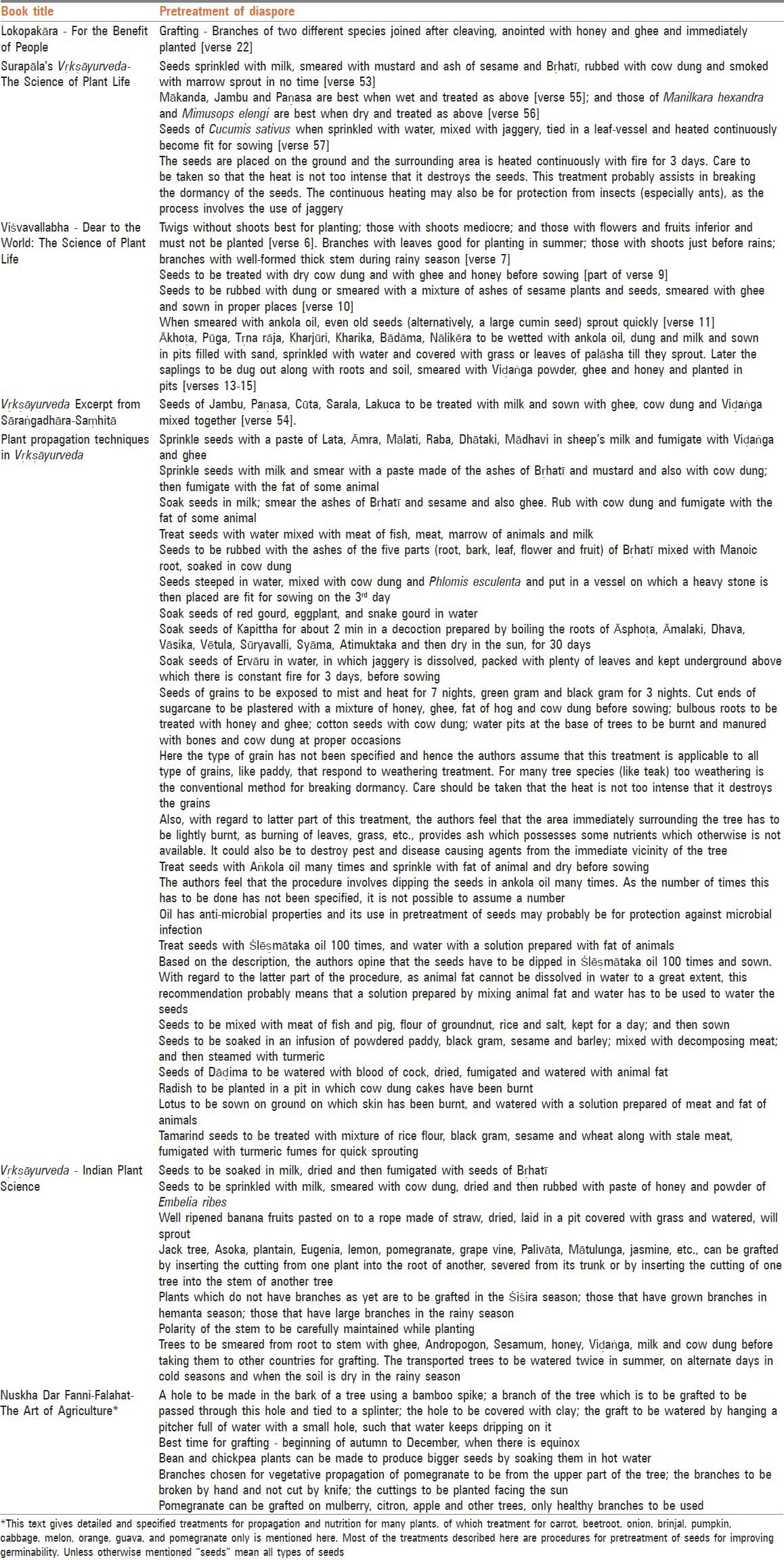

Table 2.

Summary of procedures for pretreatment mentioned in some important Vṛkṣāyurveda texts

Surapāla's Vṛkṣāyurveda also classifies seeds as those that need to be treated when “wet” and “dry.” These probably correspond to recalcitrant and orthodox seeds, respectively, where the former cannot be dried and stored, while the latter can.

Pretreatments for vegetative propagules have also been described in the texts. Anointing the stem cuttings or whole plants with cow dung, ghee, Sesamum indicum, E. ribes or honey are some of the treatments. Furthermore, type of cutting and ideal season for planting the cuttings has been clearly stated.

In addition to pretreatments applicable to all seeds in general, treatments specific to specific plants also have been described. For example, Kaśyapīyakṛṣisūkti (a treatise on agriculture by Kashyapa) translated by Ayachit describes a process for quick sprouting of seeds of Punica granatum.[45] The treatment consists of “watering the seeds with blood of cock, drying in the sun, followed by fumigation and watering with animal fat”.

Many of these treatments have been developed such that the procedures are combinations for good storability as well as good sprouting. Surapāla's Vṛkṣāyurveda: Excerpt from Sārangadhāra Saṃhitā and Vṛkṣāyurveda-Indian Plant Science have described a process for good storability and sprouting, which is as follows:[44,46,47]

“Seeds to be sprinkled with milk, smeared with cow dung, dried, smeared profusely with Viḍaṅga and honey. Such seeds definitely sprout.”

Similar treatments for good storability, germination and vigor have been explained in other texts such as Surapāla's Vṛkṣāyurveda-The Science of Plant Life,[44] Vṛkṣāyurveda-excerpt from Sāraṅgadhāra-Saṃhitā,[46] Plant propagation techniques in Vṛkṣāyurveda,[37] Use of animal products in traditional agriculture - A pilot project in Southern India.[23]

NUTRITION OF SEEDLINGS

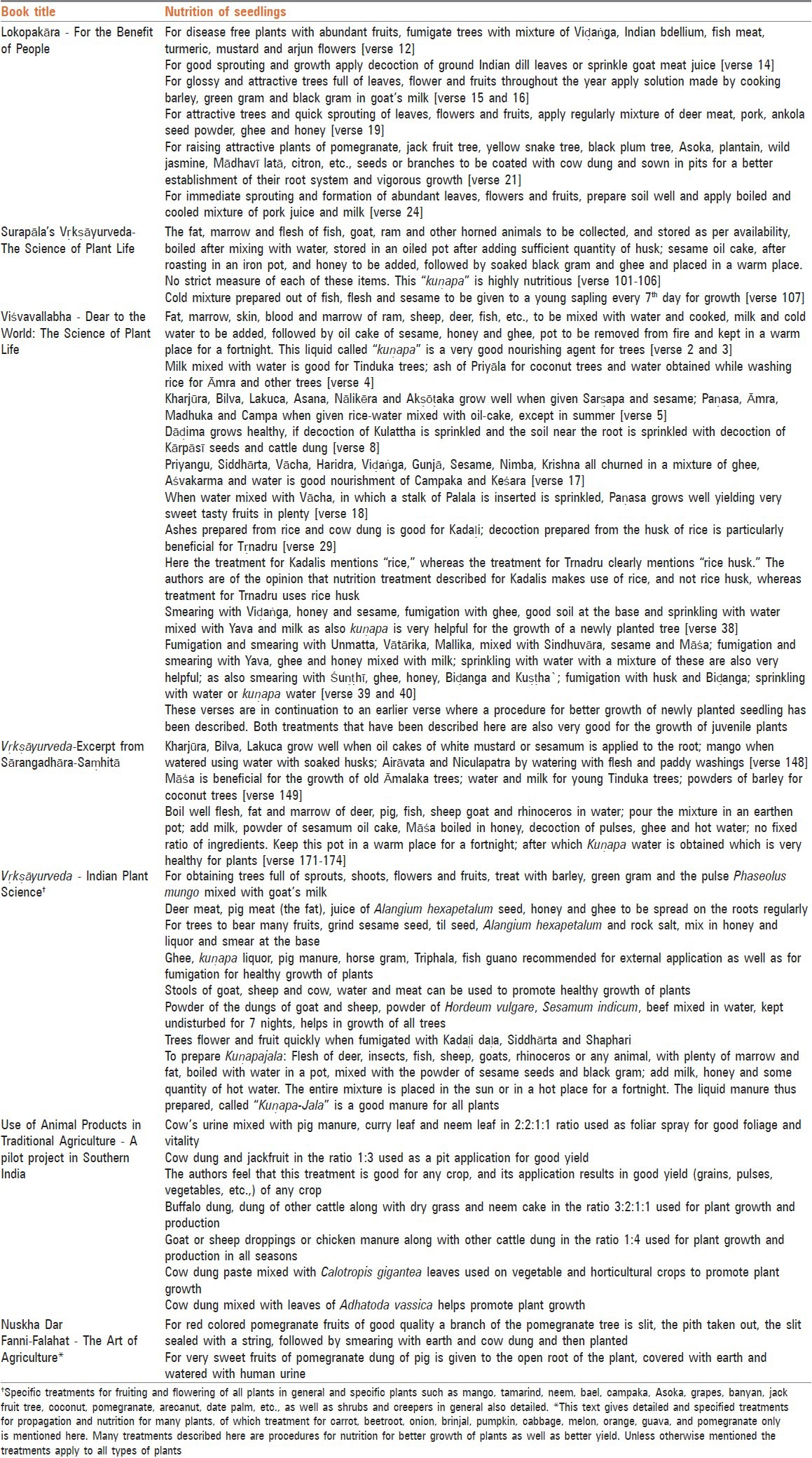

Use of meat of animals and fish, dung of animals, milk and ghee for nutrition is a common feature in most of the texts [Table 3].[23,35,38,44,46,47,48] Use of plant parts of species such as B. juncea, Sesamum indicum and A. salviifolium for nutrition has also been mentioned. In addition to general nutrition treatments, specific treatments for specific plants have also been detailed in all the texts.

Table 3.

Summary of procedures for nutrition treatment mentioned in some important Vṛkṣāyurveda texts

Viśvavallabha, Surapāla's Vṛkṣāyurveda, Vṛkṣāyurveda: Excerpt from Sāraṅgadhāra-Saṃhitā and Vṛkṣāyurveda-Indian Plant Science have detailed the process of preparation of a special formulation called “Kuṇapajala”.[35,44,46,47] This is prepared from meat, black gram, milk, ghee, and other ingredients and is a highly nutritious formulation, which can be applied to all plants. The method of preparation of kuṇapajala as mentioned in these texts is as follows:

“Boil flesh, fat and marrow of goat, sheep, fish, deer, rhinoceros, etc., with water in a pot. To this, milk and water are added, followed by sesame oil cake, black gram, honey and ghee. To this sufficient quantity of husk is added. The pot is then kept in a warm place for a fortnight to ferment. The liquid manure obtained is ‘kuṇapa’ and is highly nutritious.”

It has also been mentioned in these publications that for preparation of kuṇapajala, there is no strict measure of the ingredients to be used. They can be taken as per availability. In more recent times, experiments have been conducted to test the efficacy of kuṇapajala and have been found to be effective.[41]

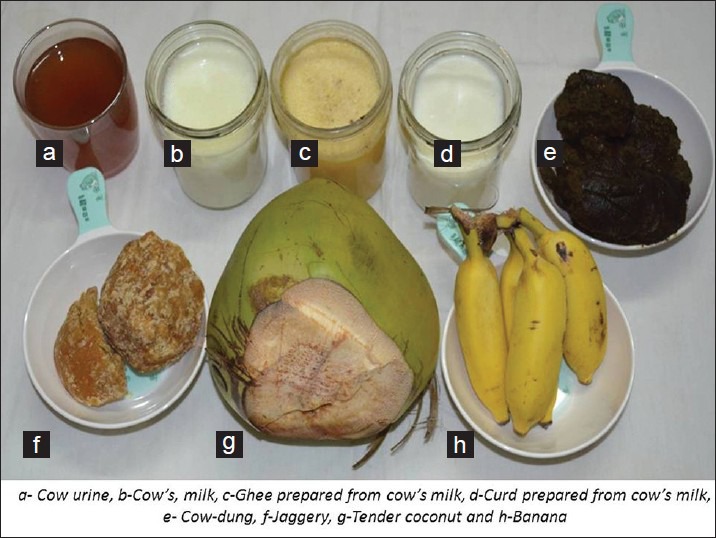

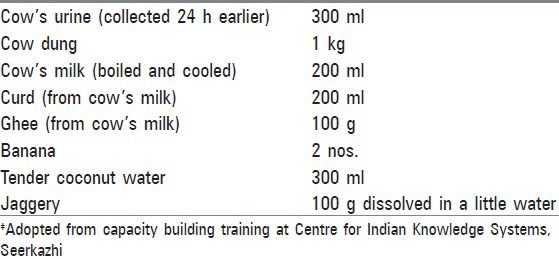

In addition to information from published literature, interviews with farmers have revealed the use of another formulation for nutrition, known as “pañcagavyam.” The main ingredients of this formulation are milk, curd, ghee, dung and urine of cow, and hence the name “pañcagavyam,” meaning prepared from five ingredients obtained from cow. Although, traditionally, this formulation was prepared using the five products mentioned above, modified pañcagavyam is prepared, using some additional ingredients. The ingredients [Figure 2] used for this preparation and the methodology for its preparation are described in Tables 4 and 5. The pañcagavyam [Figure 3] thus prepared has a shelf life of 3 months. A 3% solution prepared by adding water to the modified pañcagavyam can be used once in 15 days for best results.

Figure 2.

Ingredients for preparation of pancagavyam

Table 4.

Ingredients required for preparing modified Pañcagavyam‡ (to be used for 1 acre)

Table 5.

Method of preparation of Panchagavyam‡

Figure 3.

Pancagavyam

Some recent studies have shown the benefits of certain formulations such as pañcagavyam and kuṇapajala on the growth of plants.[39,40,41,42,43] However, such studies are very few and not exhaustive. Moreover, utility of the other procedures mentioned in the Vṛkṣāyurveda texts have neither been popularized nor studied. The use of pañcagavyam, kuṇapajala and other procedures mentioned in the various texts can be studied further for efficacy and if found to be suitable can be adopted for the various steps involved in development of organic nursery protocol for medicinal plants. A majority of the raw materials used in these procedures are by-products obtained from other activities and are easily available around us. The procedures are easy and economical too, which is an added advantage. However, a few preparations are mentioned in the Vṛkṣāyurveda texts, which make use of raw materials such as meat and other products of deer, wild boar and other animals. In the present context, it might not be possible to use many of these raw materials due to legal issues. Studies can be initiated that can focus on viable alternatives to these, but having the same efficacy.

From the review, it was also observed that major centers carrying out Vṛkṣāyurveda-related work are few; some of them are CIKS, Chennai; Asian Agri-History Foundation (AAHF), Secunderabad and National Institute of Vṛkṣāyurveda, Jhansi. Prof. Nene and his group (the AAHF) are promoting Vṛkṣāyurveda in a big way. A dedicated journal on the subject is published by his center at Secunderabad. CIKS, Chennai is involved in promoting organic farming and works along with farmers belonging to various villages in Tamil Nadu. They are also involved in testing and validation of indigenous knowledge of agriculture by rapid assessment of traditional agricultural practices. As a result of their experiments, as well as that of Indian Council of Agricultural Research, it has been able to prove, using modern research procedures, beyond doubt that much of this traditional knowledge is valid. Many indigenous techniques and procedures applicable in traditional agriculture have been developed by the CIKS. The National Institute of Vṛkṣāyurveda in Jhansi has only initiated some work in this area, and no regular publications are brought out by them as yet.

The review of literature, including those dealing with conventional nursery technology, has also revealed that nursery protocols for many of the herbaceous medicinal plants have been developed. Propagation protocols for many tree species, especially those that yield timber, have also been developed. However, there is a gap in the understanding of organic propagation methodology to be followed for many of the species yielding non-timber forest products, especially medicinal plants. Development of nursery and plantation protocols for these perennial medicinal plant species will not only increase the availability of raw drugs for the herbal industry, but also help in decreasing pressure on natural resources.

A perusal of the above also reveals that most publications are dealing with minimal aspects of plant growth and a monographic treatise is generally lacking.

CONCLUSION

Although the use of chemical inputs in various stages of nursery growth result in visibly more robust plants, their negative impact on nutritional quality of plants as well as the environment is becoming evident with time. The ancient texts, in addition to other plant related aspects, also detail methodologies to be followed for production of nursery seedlings. These traditional methods used by our farmers, unlike chemical dependent techniques, will certainly have no adverse effect on the environment as they are prepared from naturally available raw materials which are biodegradable. Moreover, these raw materials are both locally available and also economical. Their use in the present times has been minimal due to lack of modern scientific evidence of their efficiency and activity. Greater incorporation of suitable traditional techniques during development of nursery protocol, along with currently available practices, will definitely result in production of quality planting material better suited for large scale plantation programs.

Many of the raw materials listed in the Vṛkṣāyurveda texts, such as flesh and bone of animals, husk, oil cakes, dung and urine of cattle, etc., are waste products and reutilization and recycling of these products will also result in their effective waste management.

In addition to development of nursery technology for the perennial medicinal plants, it will also enhance health and livelihood security of the communities involved as well as the health of the environment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are thankful to Mr. Darshan Shankar, Vice-Chancellor, ITD-HST, Bangalore, for his encouragement, guidance and critical inputs, and also for granting permission to avail the facilities at ITD-HST during this study. Mr. A.V. Balasubramanian, Director, Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems (CIKS), Chennai and Dr. Y.L. Nene, Chairman, Asian Agri-History Foundation, Secunderabad are also gratefully acknowledged for their constant support and guidance for pursuing this research. We thankfully acknowledge the support we received from the librarians at Kerala Forest Research Institute, Thrissur, Institute of Wood Science and Technology, Bangalore, Saraswati Mahal Library, Tanjore and CIKS, Chennai by way of granting us permission to use their facilities. We are also grateful to Dr. Venugopal Nair, CEI, ITD-HST for his valuable inputs during this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nill

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roy BP. Vrksāyurveda in ancient India. In: Gopal L, Srivastava VC, editors. History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization. Part I – History of Indian Agriculture (up to 1200 AD) V. Delhi: Centre for Studies in Civilisations; 2008. pp. 550–96. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subhashini S, Arumugasamy S, Vijayalakshmi K, Balasubramanian AV. Chennai: Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems; 2001. Vṛkṣāyurveda – Āyurveda for Plant; pp. 01–15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kottakkal: Arya Vaidya Sala; 1997. Anonymous. Draft Manuscript – IDRC Project – Medicinal Plants (India)- Final Report. [Google Scholar]

- 4.New Delhi: National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources; 2009. Conservation and Collection of Seed Germplasm of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, 3-12 Nov, 2009, Training Manual of NBPGR. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thrissur: Kerala Forest Research Institute; 2009. Collection, Processing and Storage of Seeds of Medicinal Plants and Management of Seed Centre under FRLHT Programme, 8-11 June,2009, Report of the Training Programme Conducted by KFRI. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey LH. New York: Macmillan; 1920. The Nursery-Manual-A Complete Guide to the Multiplication of Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haridasan K, Sarmah A, Bhuyan LR, Hegde SN, Ahlawat SP. Itanagar: State Forest Research Institute; 2003. SFRI Information Bulletin No. 16-Field Manual for Propagation and Plantation of Medicinal Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lal JB. Delhi: International Book Distributors; 2003. Tropical Silviculture-New Imperatives, New Systems. [Google Scholar]

- 9.New Delhi: National Medicinal Plants Board; 2004. Cultivation of Selected Medicinal Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patwardhan A, Vasudeva R. Sirsi: RANWA, in Collaboration with College of Forestry; Undated; Nursery Techniques for Threatened Medicinal Plant Species from Western Ghats of India. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramprasad, Kandya AK. New Delhi: Associated Publishing Company; 1992. Handling of Forestry Seeds in India. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sumy O, Ved DK, Krishnan R. Bangalore: Foundation for Revitalisation of Local Health Traditions; 2000. Tropical Indian Medicinal Plants-Propagation Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Troup RS. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1921. The Silviculture of Indian Trees. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atal CK, Kapur BM, editors. Jammu-Tawi: Regional Research Laboratory, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research; 1982. Cultivation and utilization of medicinal plants. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimapur: Government of Nagaland; Undated; Anonymous. Agro-Forestry Technology of Important Species of Medicinal Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bisht NS, Ahlawat SP. Itanagar: State Forest Research Institute; 1999. Seed Technology, SFRI Information Bulletin No. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bisht NS, Ahlawat SP, Singh UV. Itanagar: State Forest Research Institute; 2001. Nursery Techniques of Local Tree Species, SFRI Information Bulletin No. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nautiyal MC, Nautiyal BP. Dehra Dun: Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh; 2004. Agrotechniques for High Altitude Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sashidharan N, Pandalai RC. Thrissur: Kerala Forest Research Institute; 2007. Requirement of important raw drugs for Âyurvedic medicines, estimation of planting materials, developing protocols for collection, grading and seed storage for cultivation of medicinal plants of Kerala. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Worthington V. Nutritional quality of organic versus conventional fruits, vegetables, and grains. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:161–73. doi: 10.1089/107555301750164244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kutumbiah P. Hyderabad: Orient Longman Limited; 1999. Ancient Indian Medicine; pp. 01–54. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balasubramanian AV, Vijayalakshmi K, Shylaja RR, Abarna RT. Chennai: Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems; 2011. Testing and Validation of Indigenous Knowledge – The COMPAS Experience from Southern India. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balasubramanian AV, Nirmala TD, Merlin FF. Chennai: Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems; 2009. Use of Animal Products in Traditional Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balasubramanian AV. Knowledge and belief systems in the Indian subcontinent. In: Haverkort B, Hooft KV, Hiemstra W, editors. Ancient Roots, New Shoots – Endogenous Development in Practice. London: Zed Books; 2003. pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balasubramanian AV, Vijayalakshmi K, Sridhar S, Arumugaswamy S. Modern dilemmas and traditional insights. In: Haverkort B, Hooft KV, Hiemstra W, editors. Ancient Roots, New Shoots – Endogenous Development in Practice. London: Zed Books; 2003. pp. 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nene YL. Secunderabad: Asian Agri-History Foundation; 2000. Ancient and Medieval History of Indian Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nene YL. Secunderabad: Asian Agri-History Foundation; 2002. Agricultural Heritage of India. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nene YL. Secunderabad: Asian Agri-History Foundation; 2006. Bridging Gap between Ancient and Modern Technologies to increase Agricultural Productivity. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saxena RC, Choudhary SL, Nene YL. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publications Pvt. Ltd; 2009. A Textbook on Ancient History of Indian Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raychaudhuri SP, Gopal L, Subbarayappa BV. Agriculture. In: Bose DM, Sen SN, Subbarayappa BV, editors. A concise history of science in India. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy; 1971. pp. 350–70. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peter G. Italy: Food and Agricultural Organisation; 2010. [Last accessed on 13 2010 Jul 13]. Organic production of medicinal, aromatic and dye-yielding plants. With inputs from FRLHT (Ecoport version) Available from: http://ecoport.org/ ep?SearchType=earticleView and earticleId=145 and page=-2 . [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das P, Reddy SG, Geetha Rani M, Arya HPS, Das SK, Verma LR, et al. New Delhi: Indian Council of Agricultural Research; 2004. Inventory of Indigenous Technical Knowledge in Agriculture Document 1 to 5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sircar NN, Sarkar R. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications; 1996. Vrksāyurveda of Parasara (A Treatise on Plant Science) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadhale N. Secunderabad: Asian Agri-History Foundation; 1999. Kṛṣi-Parāśara (Agriculture by Parashara) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadhale N, translator. Secunderabad: Asian Agri-History Foundation; 2004. Viśvavallabha (Dear to the World: The Science of Plant Life) by Shri Mishra Chakrapani. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varier NVK. Ch. 18. Kottakkal: Arya Vaidya Sala; 2009. Vrksāyurveda (Âyurveda for Trees) History of Āyurveda. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vijayalakshmi K, Sundar KMS. Madras: LSPSS Monograph No. 10; 1993. Plant Propagation Techniques in Vṛkṣāyurveda. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ayangarya VS, translator. Secunderabad: Asian Agri-History Foundation; 2006. Lokopakāra (For the Benefit of People) by Chavundaraya. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumaravelu G, Kadamban D. Panchagavya and its effect on the growth of the green-gram cultivar K-851. Int J Plant Sci (Muzaffarnagar) 2009;4:409–14. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Venkataramana P, Murthy BN, Rao JVK, Kamble CK. Studies on the integrated effect of organic manures and Panchagavya foliar spray on mulberry (Morus alba L.) production and leaf quality evaluation through silkworm (Bombyx mori L.) rearing. Crop Res (Hisar) 2009;37:282–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohan B. Evaluation of organic growth promoters on yield of dry-land vegetable crops in India. J Org Sys. 2008;3:23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brajeshwar, Joshi AK, Dey S. Effect of Kuṇapajala and fertilizers on Senna (Cassia angustifolia Vahl.) Indian Forester. 2007;133:1235–40. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asha KV, Rajashekhara N, Chauhan MG, Ravishankar B, Sharma PP. A comparative study on growth pattern of Langali (Gloriosa superba Linn.) under wild and cultivated conditions. Ayu. 2010;31:263–6. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.72413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sadhale N, translator. Secunderabad: Asian Agri-History Foundation; 1996. Vṛkṣāyurveda (The Science of Plant Life) by Surapāla. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayachit SM, translator. Secunderabad: Asian Agri-History Foundation; 2002. Kaśyapīyakrsisūkti (A Treatise on Agriculture by Kaśyapa) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rao RSK, editor. Bangalore: Kalpatharu Research Academy; 1993. Vṛkṣāyurveda: Excerpt from Sārangadhāra Saṃhitā. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vijayalakshmi K. Maharashtra: Academy of Development Science; Vṛkṣāyurveda – Indian Plant Science. Undated. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akbar R, translator. Secunderabad: Asian Agri-History Foundation; 2000. Nuskha Dar Fanni-Falahat-The Art of Agriculture (Persian Manuscript compiled in the 17th Century by the Mughal Prince Dara Shikoh) [Google Scholar]