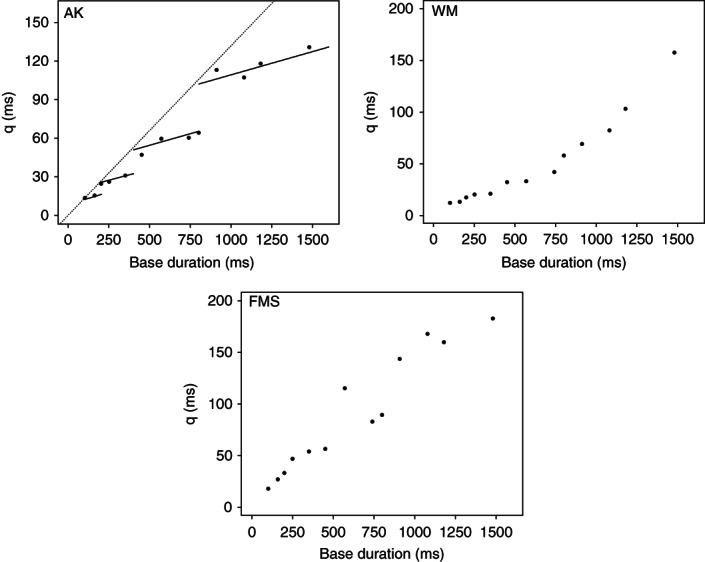

FIGURE 1.

The effects of extended practice on the precision of temporal discrimination. Participants classified intervals as ‘short’ or ‘long’ according to whether the interval was shorter/longer than a given base duration. The top left panel shows data from one participant, Alfred Kristofferson, after extensive self-experimentation; it plots the variability in temporal representation (q, calculated according to a rather specific set of assumptions) as a function of base duration.55 The dashed line summarizes performance early in training; after prolonged practice, the data points ‘unfold’ from this line to give a staircase structure where both the height of the steps and the width of the treads double in magnitude with each successive step. Kristofferson interpreted this as evidence for a ‘time quantum’. The top right and bottom panels show similar data from two other participants (WM and FMS51). The eye of faith might discern some indication of a step pattern for these participants, but it is nowhere near as pronounced as for Kristofferson and the fit of Kristofferson's theoretically motivated step function is poor. (This function posits that the ‘treads’ of the staircase have the same near-horizontal slope but both their width and the step between them periodically doubles, corresponding to systematic doubling in the base of a triangular noise distribution; see Figure 4 of the paper by Matthews and Grondin51). Rather, for WM the variability in temporal representation is a quadratic function of base duration and for FMS the relation is linear. (Reprinted with permission from Ref 51)