Significance

Qubits, the quantum-mechanical analog of classical bits, are the fundamental building blocks of quantum computers, which have the potential to solve some problems that are intractable using classical computation. This paper reports the fabrication and operation of a qubit in a double-quantum dot in a silicon/silicon–germanium (Si/SiGe) heterostructure in which the qubit states are singlet and triplet states of two electrons. The significant advance over previous work is that a proximal micromagnet is used to create a large local magnetic field difference between the two sides of the quantum dot, which increases the manipulability significantly without introducing measurable noise.

Keywords: semiconductor spin qubit, quantum nanoelectronics

Abstract

The qubit is the fundamental building block of a quantum computer. We fabricate a qubit in a silicon double-quantum dot with an integrated micromagnet in which the qubit basis states are the singlet state and the spin-zero triplet state of two electrons. Because of the micromagnet, the magnetic field difference ΔB between the two sides of the double dot is large enough to enable the achievement of coherent rotation of the qubit’s Bloch vector around two different axes of the Bloch sphere. By measuring the decay of the quantum oscillations, the inhomogeneous spin coherence time is determined. By measuring at many different values of the exchange coupling J and at two different values of ΔB, we provide evidence that the micromagnet does not limit decoherence, with the dominant limits on arising from charge noise and from coupling to nuclear spins.

Fabricating qubits composed of electrons in semiconductor quantum dots is a promising approach for the development of a large-scale quantum computer because of the approach’s potential for scalability and for integrability with classical electronics. Much recent progress has been made, and spin manipulation has been demonstrated in systems of two (1–5), three (6, 7), and four (8) quantum dots. A great deal of attention has focused on the singlet–triplet qubit in quantum dots (1, 2, 9–18), which consists of the Sz = 0 subspace of two electrons, for which the basis can be chosen to be a singlet and a triplet state. Full two-axis control on the Bloch sphere is achieved by electrical gating in the presence of a magnetic field difference ΔB between the two dots. In previous experiments (2, 9–14), ΔB arises from coupling to nuclear spins in the material, and slow fluctuations in these nuclear fields lead to inhomogeneous decoherence times that, without special nuclear state preparation, typically are shorter than the period of the quantum oscillations. In III–V materials, ΔB is large, so fast oscillation periods of order 10 ns are achievable, but the inhomogeneous dephasing time is also ∼10 ns, so that oscillations from ΔB are overdamped, ending before a complete cycle is observed (2). The fluctuations of the nuclear spin bath can be mitigated to some extent (10), but inhomogeneous dephasing times in III–V materials are short enough that high-fidelity control is still very challenging. Coupling to nuclear spins in silicon is substantially weaker, leading to longer coherence times, but also smaller field differences and hence slower quantum oscillations (14, 19).

Here, we report the operation of a singlet–triplet qubit in which the magnetic field difference ΔB between the dots is imposed by an external micromagnet (20, 21). Because the field from the micromagnet is stable in time, a large ΔB can be imposed without creating inhomogeneous dephasing. We present data demonstrating underdamped quantum oscillations, and, by investigating a variety of voltage configurations and two ΔB configurations, we show that the micromagnet indeed increases ΔB without significantly increasing inhomogeneous dephasing rates induced by coupling to nuclear spins.

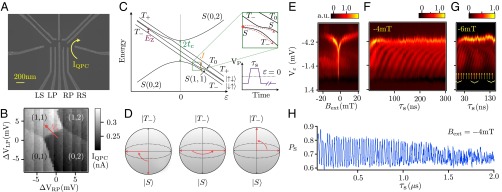

A top view of the double-quantum dot device, which is fabricated in a Si/SiGe heterostructure, is shown in Fig. 1A; fabrication techniques are discussed in Materials and Methods, and an optical image of the micromagnet can be found in SI Appendix. The charge occupation of the two sides of the double dot is determined by measuring the current through a quantum point contact (QPC) next to one of the dots, as shown in Fig. 1A. Fig. 1B shows a charge stability diagram, obtained by measuring the current through the QPC as a function of gate voltages on the left plunger (LP) and right plunger (RP); the number of electrons on each side of the dot is labeled. The qubit manipulations are performed in the (1, 1) region (detuning ε > 0), and initialization and readout are carried out in the (0, 2) region (ε < 0). Fig. 1C shows the energy-level diagram at small but nonzero magnetic field. The three triplet states T− = |↓↓〉, , and T+ = |↑↑〉 are split from each other by the Zeeman energy EZ = gμBBave, where g is the gyromagnetic ratio, μB is the Bohr magneton, and Bave is the average of the total magnetic field. A difference in the transverse magnetic fields on the dots, either from the external micromagnet or from nuclear hyperfine fields, mixes the singlet S and triplet T− states and turns the S-T− crossing into an anticrossing. This avoided crossing enables the observation of a spin funnel where the S-T− mixing is fast (2) as well as quantum oscillations between S and T− (22). The spin funnel is shown in Fig. 1E, and the S-T− oscillations are shown in Fig. 1 F and G. The applied pulse in Fig. 1E is a simple one-stage pulse along the detuning direction with fixed amplitude (shown in Fig. 1C, Inset), repeated at a rate of 33 kHz, which is slow enough for spin relaxation to reinitialize to the singlet before application of the next pulse (23, 24). The lever arm α, the conversion between detuning energy ε and gate voltage Vε, is 35.4 μeV/mV. See SI Appendix for methods used to extract α and convert the measured QPC current to the probability of being in the S state at the end of the applied pulse. The spin funnel is obtained by sweeping along the detuning direction (i.e., sweeping Vε) with the pulse on, and stepping the external magnetic field Bext. When the pulse tip reaches the S-T− anticrossing, a strong resonance signal is observed, corresponding to strong mixing of S-T− states. Because right at the anticrossing EZ ≃ J, we can map out J at small ε by sweeping the magnetic field. The center of the spin funnel occurs when the applied field cancels out the average field from the micromagnet, which indicates Bave ≃ 2.5 mT. The tunnel coupling tc ∼ 3.4 μeV is estimated from the dependence of the location of the spin funnel on magnetic field (2). The pulse rise time of 10 ns ensures nearly adiabatic passage over the S(0, 2) to S(1, 1) anticrossing, with a nonadiabatic transition probability <0.1% (25).

Fig. 1.

(A) Scanning electron micrograph of a device identical to the one used in the experiment before deposition of the gate dielectric and accumulation gates. An optical image of a complete device showing the micromagnet is included in SI Appendix. Gates labeled left side (LS) and right side (RS) are used for fast pulsing. The curved arrow shows the current path through the QPC used as a charge sensor. (B) IQPC measured as a function of VLP and VRP yields the double-dot charge stability diagram. Electron numbers in the left and right dot are indicated on the diagram. The red arrow denotes the direction in gate voltage space that changes the detuning ε between the quantum dots. (C) Schematic energy diagram near the (0, 2) to (1, 1) charge transition, showing energies of singlet S and triplet T states as functions of ε. The exchange energy splitting J between S and T0, the Zeeman splitting EZ between T− and T0, and the tunnel coupling tc are also shown. At large ε, in the presence of a field difference between the two dots, S and T0 mix, and the corresponding energy eigenstates are |↑↓〉 and |↓↑〉. At small ε, the small transverse field from the micromagnet and the nuclear fields turns the S-T− crossing into an anticrossing (zoom in). Pulsing through this anticrossing with intermediate velocity transforms S into a superposition of S and T−, leading to Landau–Stückelberg–Zener oscillations at the frequency corresponding to the S-T− energy difference (22). The pulse used to observe the spin funnel and S-T− oscillations shown in E is also shown, where the pulse voltage VP is applied along the detuning axis. (D) Bloch sphere representation of π rotation of S and T− states with 50% initialization into each state. (E) Spin funnel (2) measurement of the location of the S-T− anticrossing as a function of external magnetic field Bext and Vε. The data were acquired by sweeping along the detuning direction with the pulse on, with the vertical axis reporting the value of the detuning at the base of the pulse. The spin funnel occurs when S-T− mixing is fast, which locates the relevant anticrossing. (F and G) S-T− oscillations acquired at different external B fields. The oscillation frequency increases with increasing Bext. The slower oscillations in G with period ∼80 ns and labeled with the curly brackets are S-T0 oscillations, which are investigated in more detail in Figs. 2 and 3. The S-T− oscillations in G are labeled with arrows. (H) Singlet probability as a function of pulse duration τs at external magnetic field B = −4 mT and base detuning Vε ≃ −2.8 mV.

By increasing the rise time of the pulse, so that it is slower than that used to observe the spin funnel, the voltage pulse can be used to cause S to evolve into a superposition of the S and T− states. In this case, the pulse remains adiabatic with respect to the S(0, 2)–S(1, 1) anticrossing; it is, however, only quasi-adiabatic with respect to the S-T− anticrossing, enabling use of the Landau–Zener mechanism to initialize a superposition between states S and T− (Fig. 1C, Inset) (22, 26–28). Because the voltage pulse takes these states to larger detuning, an energy difference arises between the pair of states, and there is a relative phase accumulation between them. The return pulse leads to quantum interference between these two states and to oscillations in the charge occupation as a function of the acquired phase. Fig. 1D illustrates the ideal case, in which the rising edge of the pulse transforms S into an equal superposition of S and T−, followed by accumulation of a relative phase difference of π after pulse duration τS. Fig. 1F shows S-T− oscillations at Bext = −4 mT, obtained by applying a pulse with a rise time of 45 ns. Fig. 1H reports a line scan of the singlet probability for S-T− oscillations measured at Bext = −4 mT; for this measurement, the tip of the voltage pulse reaches large enough detuning that is essentially constant and independent of detuning. From this data we extract a dephasing time of 1.7 μs by fitting the oscillation amplitude to a Gaussian decay function of the pulse duration τS. The S-T− oscillations observed here are longer-lived than those observed in GaAs (22), presumably in part because Si has weaker hyperfine fields (29). However, the visibility here is similar to that in GaAs, indicating that decoherence is still important in limiting the ability to tune the pulse rise time to achieve equal amplitude in the S and T− branches of the Landau–Zener beam splitter (22, 26–28). Fig. 1G shows a similar measurement for which we used a slightly faster (16 ns) rise time for the pulse, the effect of which is to increase the overlap of the wavefunction with the singlet state S; as a result, both S-T− oscillations and S-T0 oscillations are visible in this plot, which was acquired at Bext = −6 mT. The faster oscillations with period 10 ns, marked with the small arrows in Fig. 1G, are the S-T− oscillations. The slower oscillations, marked with the curly brackets, are the S-T0 oscillations. As we discuss below, these latter oscillations can be made dominant by further modifications of the manipulation pulse, and for these oscillations the micromagnet plays a critical role in enhancing the rotation rate on the S-T0 Bloch sphere.

We investigate the S-T0 oscillations, which correspond to a gate rotation of the S-T0 qubit, in more detail by changing the applied magnetic field Bext to −30 mT, and by working with faster pulse rise times. Here the S-T− anticrossing occurs at negative ε, as shown in Fig. 2A, making it easier to pulse through that anticrossing quickly enough so that the state remains S. In this situation, the relevant Hamiltonian H for ε > 0, in the S-T0 basis, is

| [1] |

Here, J is the exchange coupling and h = gμBΔB is the energy contribution from the magnetic field difference. The angle θ between the rotation axis and the z axis of the Bloch sphere satisfies tanθ = h/J, and the rotation angular frequency . Both θ and ω depend on ε, because J varies with ε.

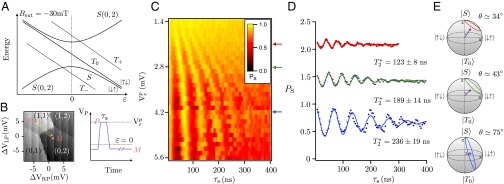

Fig. 2.

(A) Schematic energy level diagram near the (0, 2)–(1, 1) charge transition at external field Bext = −30 mT. (B) Pulse sequence used to observe S-T0 oscillations. Starting at point M in the S(0, 2) ground state, a fast adiabatic pulse into (1, 1) is applied [it is adiabatic for the S(0, 2)–S(1, 1) anticrossing and sudden for the S(1, 1)-T0 anticrossing], to point P, where the exchange coupling J is comparable to or less than h, the energy from the magnetic field difference. The speed and axis of the rotation on the Bloch sphere during the pulse of duration τS depend on both J and h. Readout is performed by reversing the fast adiabatic pulse, which converts S(1, 1) to S(0, 2) but does not change the charge configuration of T0. (C) Probability PS of being in state S as a function of the detuning voltage at the pulse tip, , and the pulse duration τs. Here, the measurement point M in the (0, 2) charge state is fixed while and τs are varied. (D) PS as a function of τs, extracted from the data in C at three different values of Vε. Each trace is fit to the product of a cosine and a Gaussian (30, 31), with amplitude, frequency, phase, and decay time as free parameters (solid curves). The decay time is listed for each trace. Each trace is offset by 0.6 for clarity. (E) Bloch spheres showing the rotations corresponding to each trace in D. The angle θ between the rotation axis and the z axis is labeled for each case.

Rotations around the x axis of the Bloch sphere (the “ΔB gate”) are implemented using the simple one stage pulse shown in Fig. 2B, starting from point M in the (0, 2) charge state. The pulse rise time of a few nanoseconds is slow enough that the pulse is adiabatic through the S(0, 2) to S(1, 1) anticrossing. As ε increases, the eigenstates transition from S(1, 1) and T0 to other combinations of |↑↓〉 and |↓↑〉, and in the limit of ε → ∞, the eigenstates become |↑↓〉 and |↓↑〉. The voltage pulse applied is sudden with respect to this transition in the energy eigenstates, so that immediately following the rising edge of the pulse the system remains in S(1, 1). At large detuning, J ≤ h, and S-T0 oscillations are observed following the returning edge of the pulse. These oscillations arise from the x component of the rotation axis and have a rotation rate that is largely determined by the magnitude of h. Fig. 2C shows the singlet probability PS plotted as a function of the detuning voltage at the pulse tip, , and pulse duration τS. The data in the top one-third of the figure were acquired with a pulse rise time of 2.5 ns, and the data shown in the bottom two-thirds of the figure were acquired using a 5-ns rise time. As is clear from Fig. 2 C and D, J decreases as ε increases, so the oscillation angular frequency becomes smaller and approaches h/ℏ as J → 0. The visibility of the oscillations is largest at large , because in that regime the rotation axis is closest to the x axis, as shown in Fig. 2E. By fitting traces from Fig. 2C to the product of a cosine and a Gaussian (30), we extract the inhomogeneous dephasing time as a function of ε. Based on the rotation period at large ε, we estimate h ∼ 60.5 neV, which corresponds to an X-rotation rate of 14 MHz. The rotation rate we observe here is much faster than the X-rotation rate achievable without micromagnets in Si, which is ∼460 kHz (14); micromagnets closer to the quantum dots offer the potential for even faster rotation rates than those reported here. Using feedback to prepare the nuclear spins in GaAs quantum dots, X-rotation rates of 30 MHz have been reported (18), comparable but slightly faster than the rates we achieve here without such preparation.

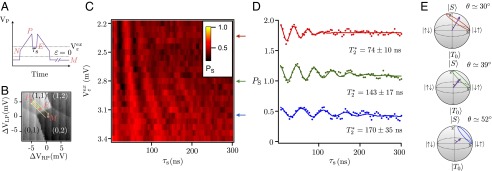

Fig. 3 shows oscillations around the z axis of the Bloch sphere, obtained by applying the exchange pulse sequence pioneered in (2). Starting from point M in S(0, 2), we first ramp from M to N at a rate that ensures fast passage through the S(0, 2)-T− anticrossing, converting the state to S(1, 1), and then ramp adiabatically from N to P, which initializes to the ground state in the J < h region. The pulse from P to E increases J suddenly so that it is comparable to or bigger than h, so that the rotation axis is close to the z axis of the Bloch sphere. Readout is performed by reversing the ramps, which projects |↓↑〉 into the S(2, 0) state, enabling readout. Fig. 3C shows the singlet probability PS as a function of τS and the detuning of the exchange pulse (point E in Fig. 3B) in a range of ε where J ≳ h. As decreases, the oscillation frequency increases, because J is increasing. The oscillation visibility also increases as the rotation axis moves toward the z axis, as shown in Fig. 3 D and E. The inhomogeneous dephasing time , extracted by fitting the time dependence of PS in Fig. 3D to the product of a Gaussian and a cosine function, decreases as J increases, which we argue is evidence that charge noise is limiting coherence in this regime (see below and Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

(A and B) Pulse sequence used to observe S-T0 oscillations when J > h. We initialize into the S(1, 1) state by preparing the S(0, 2) ground state at point M and ramping adiabatically through the (0, 2)–(1, 1)S anticrossing to an intermediate point N and then to P, where the singlet and triplet states are no longer energy eigenstates. Decreasing ε suddenly brings the state nonadiabatically to a value of the detuning where J is comparable or greater than h, inducing coherent rotations. The Bloch vector rotates around the new axis for a time τs. Reversing the sequence of ramps projects the state into S(0, 2) for readout. (C) Probability PS of observing the singlet as a function of the detuning voltage of the exchange pulse and pulse duration τs with the measurement point M fixed in the (0, 2) charge state. (D) PS as a function of τs, extracted from the data in C at three different values of . Each trace is offset by 0.7 for clarity. Solid curves are fits to the product of a cosine and a Gaussian (30), with amplitude, frequency, phase, and decay time as free parameters. (E) Bloch spheres showing rotations around the axes corresponding to each trace in D. The angle θ between the rotation axis and the z axis is labeled for each case.

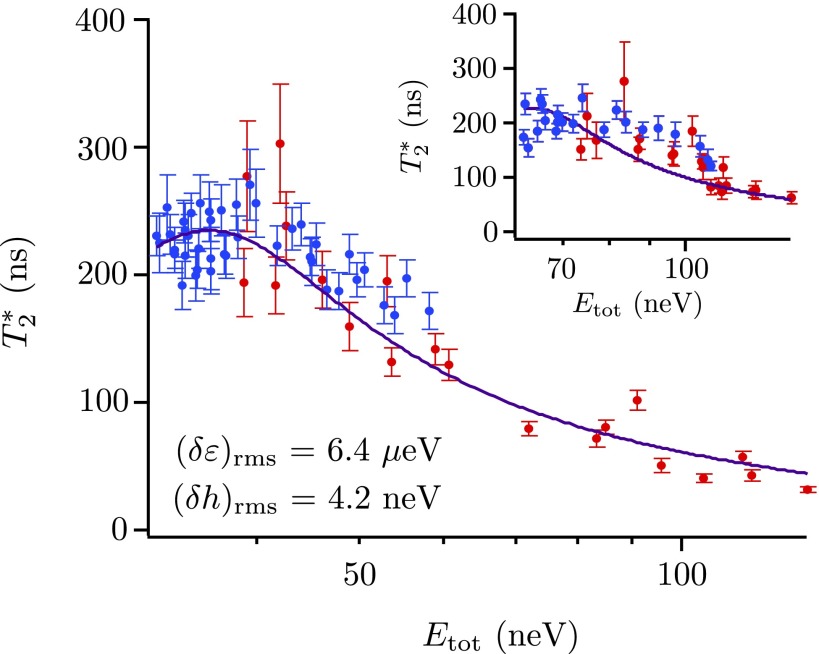

Fig. 4.

Dependence of the inhomogeneous dephasing time on rotation energy , where J is the exchange coupling and h is the energy corresponding to the magnetic field difference between the dots. (Inset) Plot of the extracted values of for h ≃ 60.5 neV. Red data points are values obtained using the exchange pulse sequence (Fig. 3), and blue data points are values obtained using the ΔB pulse (Fig. 2). Main panel: plotted vs. Etot for h ≃ 32 neV, extracted from data shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S3. Red data points are obtained using the exchange pulse sequence (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B), and blue data points are obtained using the ΔB pulse (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). The solid lines in the main panel and in Inset are plots of Eq. 2 with the same values of δε, the rms fluctuation in the detuning, and δh, the rms fluctuation of the magnetic field difference, which were obtained by fitting the data for as function of Etot at h ≃ 32 neV to Eq. 2. The good agreement of the same form with both data sets is strong evidence that the inhomogeneous dephasing is dominated by charge noise and hyperfine fields and does not depend on the magnetization of the micromagnet.

We also implemented both the ΔB and exchange gate sequences after performing a different cycling of the external magnetic field, which resulted in a different value of ΔB, corresponding to h ≃ 32 neV. The results obtained are qualitatively consistent with those shown in Figs. 2 and 3 (data shown in the SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

We now present evidence that the inhomogeneous dephasing is dominated by detuning noise and by fluctuating nuclear fields, and that it does not depend on the field from the micromagnet. Following ref. 18, we write , where δEtot = δJ(∂Etot/∂J) + δh(∂Etot/∂h), with δEtot the fluctuation in Etot, δJ the fluctuation in J, and δh the fluctuation in h. We assume that the fluctuations in h and J are uncorrelated. If fluctuations in J are dominated by fluctuations in the detuning, δε, then δJ ∼ δε(dJ/dε), and if fluctuations in h are dominated by nuclear fields, then δh is independent of ε, leading to

| [2] |

with δεrms and δhrms both independent of Etot as well as h. We use the measured Etot vs. ε to extract J(ε), which is well-described by an exponential, J(ε) ≃ J0exp(−ε/ε0), consistent with ref. 18 in the same regime (SI Appendix). In Fig. 4 we fit using the experimentally determined dJ/dε, the measured Etot, and constant values δεrms = 6.4 ± 0.1 μeV and δhrms = 4.2 ± 0.1 neV. The fit is good, and the values of δεrms and δhrms agree well with previous reports of charge noise and fluctuations in the nuclear field in similar devices and materials (14, 29, 30, 32–34). Fig. 4 Inset, which shows data obtained at a larger h, demonstrates that is well-described by Eq. 2 with the same δεrms and δhrms, providing evidence that changing the magnetization of the micromagnet does not significantly affect the qubit decoherence. Eq. 2 and Fig. 4 also make it clear that is larger for larger detunings, because charge noise has much less effect away from the primary anticrossing.

In summary, we have demonstrated coherent rotations of the quantum state of a singlet–triplet qubit around two different directions of the Bloch sphere. Measurements of the inhomogeneous dephasing time at a variety of exchange couplings and two different field differences demonstrate that using an external micromagnet yields a large increase in the rotation rate around one axis on the Bloch sphere without inducing significant decoherence. Because the materials fabrication techniques are similar for both quantum dot-based qubits and donor-based qubits in semiconductors (35), it is reasonable to expect micromagnets also should be applicable to donor-based spin qubits (36–38). Micromagnets allow a difference in magnetic field to be generated between pairs of dots that does not depend on nuclear spins, and thus offer a promising path toward fast manipulation in materials with small concentrations of nuclear spins, including both natural Si and isotopically enriched 28Si.

Materials and Methods

All measurements reported in this manuscript were made on a double-quantum dot device fabricated in an undoped Si/Si0.72Ge0.28 heterostructure with a 12-nm-thick Si quantum well located 32 nm below the heterostructure surface. The double-quantum dot is defined using two layers of electrostatic gates (39–44). The lower layer of depletion gates is shown in Fig. 1A. The upper and lower layer of gates are separated by 80 nm of Al2O3 deposited via atomic layer deposition. The upper layer of gates is positively biased to accumulate a 2D electron gas in the Si well. The micromagnet, a rectangular thin film of cobalt, is deposited via electron-beam evaporation on top of the gate structure, 1.78 μm from the double-dot region (SI Appendix). A uniform in-plane magnetic field Bext is applied, and cycling Bext to relatively large values is used to change the magnetization of the micromagnet. All measurements were made in a dilution refrigerator with an electron temperature of ∼120 mK, as determined using the method of ref. 45.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Rzchowski for help in characterizing cobalt films, and acknowledge useful correspondence with W. Coish and F. Beaudoin. This work was supported in part by Army Research Office Grant W911NF-12-0607; National Science Foundation (NSF) Grants DMR-1206915 and PHY-1104660; and the Department of Defense. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressly or implied, of the US Government. Development and maintenance of growth facilities used for fabricating samples is supported by Department of Energy Grant DE-FG02-03ER46028, and nanopatterning made use of NSF-supported shared facilities (DMR-1121288).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1412230111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Levy J. Universal quantum computation with spin-1/2 pairs and Heisenberg exchange. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;89(14):147902. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.147902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petta JR, et al. Coherent manipulation of coupled electron spins in semiconductor quantum dots. Science. 2005;309(5744):2180–2184. doi: 10.1126/science.1116955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nowack KC, et al. Single-shot correlations and two-qubit gate of solid-state spins. Science. 2011;333(6047):1269–1272. doi: 10.1126/science.1209524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi Z, et al. Fast coherent manipulation of three-electron states in a double quantum dot. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3020. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim D, et al. Quantum control and process tomography of a semiconductor quantum dot hybrid qubit. Nature. 2014;511:70–74. doi: 10.1038/nature13407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaudreau L, et al. Coherent control of three-spin states in a triple quantum dot. Nat Phys. 2012;8:54–58. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medford J, et al. Self-consistent measurement and state tomography of an exchange-only spin qubit. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8(9):654–659. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shulman MD, et al. Demonstration of entanglement of electrostatically coupled singlet-triplet qubits. Science. 2012;336(6078):202–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1217692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reilly DJ, et al. Suppressing spin qubit dephasing by nuclear state preparation. Science. 2008;321(5890):817–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1159221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foletti S, Bluhm H, Mahalu D, Umansky V, Yacoby A. Universal quantum control of two-electron spin quantum bits using dynamic nuclear polarization. Nat Phys. 2009;5:903–908. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barthel C, Reilly DJ, Marcus CM, Hanson MP, Gossard AC. Rapid single-shot measurement of a singlet-triplet qubit. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;103(16):160503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.160503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barthel C, Medford J, Marcus CM, Hanson MP, Gossard AC. Interlaced dynamical decoupling and coherent operation of a singlet-triplet qubit. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;105(26):266808. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.266808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bluhm H, et al. Dephasing time of GaAs electron-spin qubits coupled to a nuclear bath exceeding 200μs. Nat Phys. 2011;7:109–113. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maune BM, et al. Coherent singlet-triplet oscillations in a silicon-based double quantum dot. Nature. 2012;481(7381):344–347. doi: 10.1038/nature10707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi Z, et al. Tunable singlet-triplet splitting in a few-electron Si/SiGe quantum dot. Appl Phys Lett. 2011;99(23):233108. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otsuka T, Sugihara Y, Yoneda J, Katsumoto S, Tarucha S. Detection of spin polarization utilizing singlet and triplet states in a single-lead quantum dot. Phys Rev B. 2012;86(8):081308. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Studenikin SA, et al. Quantum interference between three two-spin states in a double quantum dot. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;108(22):226802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.226802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dial OE, et al. Charge noise spectroscopy using coherent exchange oscillations in a singlet-triplet qubit. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;110(14):146804. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.146804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zwanenburg FA, et al. Silicon quantum electronics. Rev Mod Phys. 2013;85(3):961–1019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pioro-Ladrière M, Tokura Y, Obata T, Kubo T, Tarucha S. Micromagnets for coherent control of spin-charge qubit in lateral quantum dots. Appl Phys Lett. 2007;90(2):024105–024105-3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pioro-Ladrière M, et al. Electrically driven single-electron spin resonance in a slanting Zeeman field. Nat Phys. 2008;4(10):776–779. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petta JR, Lu H, Gossard AC. A coherent beam splitter for electronic spin states. Science. 2010;327(5966):669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.1183628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prance JR, et al. Single-shot measurement of triplet-singlet relaxation in a Si/SiGe double quantum dot. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;108(4):046808. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.046808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi Z, et al. Fast hybrid silicon double-quantum-dot qubit. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;108(14):140503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.140503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shevchenko SN, Ashhab S, Nori F. Landau–Zener–Stückelberg interferometry. Phys Rep. 2010;492(1):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ribeiro H, Petta JR, Burkard G. Interplay of charge and spin coherence in Landau-Zener-Stückelberg-Majorana interferometry. Phys Rev B. 2013;87(23):235318. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao G, et al. Ultrafast universal quantum control of a quantum-dot charge qubit using Landau-Zener-Stückelberg interference. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1401. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Granger G, et al. 2014. The visibility study of ST+ Landau-Zener-Stückelberg oscillations without applied initialization. arXiv:1404.3636.

- 29.Assali LVC, et al. Hyperfine interactions in silicon quantum dots. Phys Rev B. 2011;83(16):165301. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersson KD, Petta JR, Lu H, Gossard AC. Quantum coherence in a one-electron semiconductor charge qubit. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;105(24):246804. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.246804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beaudoin F, Coish WA. Enhanced hyperfine-induced spin dephasing in a magnetic-field gradient. Phys Rev B. 2013;88(8):085320. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi Z, et al. Coherent quantum oscillations and echo measurements of a Si charge qubit. Phys Rev B. 2013;88(7):075416. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor JM, et al. Relaxation, dephasing, and quantum control of electron spins in double quantum dots. Phys Rev B. 2007;76(3):035315. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Culcer D, Zimmerman NM. Dephasing of Si singlet-triplet qubits due to charge and spin defects. Appl Phys Lett. 2013;102(23):232108. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morton JJ, McCamey DR, Eriksson MA, Lyon SA. Embracing the quantum limit in silicon computing. Nature. 2011;479(7373):345–353. doi: 10.1038/nature10681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pla JJ, et al. A single-atom electron spin qubit in silicon. Nature. 2012;489(7417):541–545. doi: 10.1038/nature11449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Büch H, Mahapatra S, Rahman R, Morello A, Simmons MY. Spin readout and addressability of phosphorus-donor clusters in silicon. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2017. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin C, et al. Optical addressing of an individual erbium ion in silicon. Nature. 2013;497(7447):91–94. doi: 10.1038/nature12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nordberg EP, et al. Enhancement-mode double-top-gated metal-oxide-semiconductor nanostructures with tunable lateral geometry. Phys Rev B. 2009;80(11):115331. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim WH, et al. Observation of the single-electron regime in a highly tunable silicon quantum dot. Appl Phys Lett. 2009;95(24):242102. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiao M, House MG, Jiang HW. Measurement of the spin relaxation time of single electrons in a silicon metal-oxide-semiconductor-based quantum dot. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;104(9):096801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.096801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borselli MG, et al. Pauli spin blockade in undoped Si/SiGe two-electron double quantum dots. Appl Phys Lett. 2011;99(6):063109. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ward DR, Savage DE, Lagally MG, Coppersmith SN, Eriksson MA. Integration of on-chip field-effect transistor switches with dopantless Si/SiGe quantum dots for high-throughput testing. Appl Phys Lett. 2013;102(21):213107. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eriksson MA, Coppersmith SN, Lagally MG. Semiconductor quantum dot qubits. MRS Bull. 2013;38(10):794. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simmons CB, et al. Charge sensing and controllable tunnel coupling in a Si/SiGe double quantum dot. Nano Lett. 2009;9(9):3234–3238. doi: 10.1021/nl9014974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.