Abstract

Wilms tumour is a childhood kidney cancer. Here we identify inactivating CTR9 mutations in 3 of 35 Wilms tumour families, through exome and Sanger sequencing. By contrast, no similar mutations are present in 1,000 population controls (P<0.0001). Each mutation segregates with Wilms tumour in the family and a second mutational event is present in available tumours. CTR9 is a key component of the polymerase-associated factor 1 complex which has multiple roles in RNA polymerase II regulation and is implicated in embryonic organogenesis and maintenance of embryonic stem cell pluripotency. These data establish CTR9 as a Wilms tumour predisposition gene and suggest it acts as a tumour suppressor gene.

Wilms tumour is a childhood kidney cancer that affects 1 in 10,000 children. Here the authors exome sequence 12 individuals with non-syndromic Wilms tumour from six unrelated families and find mutations in CTR9 that may increase risk of developing the disease.

Wilms tumour is a childhood kidney cancer that affects 1 in 10,000 children. Here the authors exome sequence 12 individuals with non-syndromic Wilms tumour from six unrelated families and find mutations in CTR9 that may increase risk of developing the disease.

Wilms tumour is the most common paediatric renal cancer, affecting 1 in 10,000 children. It is often described as an embryonal tumour as it arises from embryonal cells in which growth and/or differentiation has become dysregulated during development. Eighty per cent of individuals with Wilms tumour are diagnosed by 5 years of age and diagnosis after 15 years is extremely rare. Treatment of Wilms tumour is very successful with 5-year overall survival of ~90% (ref. 1).

About 2% of Wilms tumour patients have one or more relatives that have also had Wilms tumour1,2. In most Wilms tumour families, there are no other clinical features or cancers and the majority are consistent with an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance with incomplete penetrance. A small proportion of familial cases are due to WT1 mutations, 11p15 epigenetic defects or autosomal recessive conditions that include Wilms tumour, such as mosaic variegated aneuploidy syndrome and certain types of Fanconi anaemia2. Two familial Wilms tumour loci have been mapped by genome-wide linkage analysis to chromosomes 17q12-21 and 19q13, but the causative genes remain elusive3,4. Furthermore, families unlinked to either locus have been reported5. Thus, to date, the cause(s) of the majority of familial Wilms tumours is unknown.

In this study, we use exome and Sanger sequencing in familial Wilms tumour to identify new genes that predispose to Wilms tumour. We identify inactivating Cln three requiring 9 (CTR9) mutations in three of 35 Wilms tumour families, establishing CTR9, which encodes a key component of the polymerase-associated factor complex (PAF1c), as a Wilms tumour predisposition gene.

Results

We first performed exome sequencing of lymphocyte DNA from 12 affected individuals from six unrelated, non-syndromic Wilms tumour families (Table 1, Methods). We generated 39,660,686–106,571,869 reads per sample, with an average of 59,575,502 reads across the 12 samples. As many cancer predisposition genes are tumour suppressor genes, inactivated by rare protein truncating variants (PTVs), we used a PTV prioritization method to identify candidate truncating mutations for further investigation6. Specifically, we used NextGENe software (SoftGenetics) to identify and annotate all variants in the exome data. We excluded any gene with more than one PTV in 48 exomes of individuals with other conditions that were sequenced and analyzed in parallel, through the same pipelines. We next identified PTVs in the remaining genes, that were present in all affected individuals within a family and stratified the genes according to the number of families that harboured disease-segregating PTVs (Methods).

Table 1. Wilms tumour families included in study.

| Family ID | Relationship of relatives affected with Wilms tumour | Number of WT cases analyzed | Method of analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAM0072 | Two siblings | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0091 | Two siblings | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0123 | Two siblings | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0349 | Two half first cousins once removed (parent's half first cousin) | 2 | Exome sequencing |

| FAM0477 | Parent–child and possible history of more distantly affected relatives | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0480 | Two siblings | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0481 | Three first cousins | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0484 | Two first cousins. Mothers are sisters and fathers are brothers | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0485 | Two first cousins and one first cousin once removed (first cousin of obligate carrier parents) | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0486 | Parent–child. Parent has affected half-sibling and first cousin | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0487 | Uncle–child | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0488 | Two half siblings | 2 | Exome sequencing |

| FAM0489 | Two first cousins | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0491 | Two first cousins | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0492 | Parent–child | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0493 | Two siblings | 2 | Exome sequencing |

| FAM0498 | Parent–children (two children) | 2 | Exome sequencing |

| FAM0499 | Uncle–child (via unaffected obligate carrier father) | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0500 | Two first cousins | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0501 | Two individuals are second cousins (one set of grandparents are siblings) and third cousins (one set of grandparents are first cousins) | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0504 | Parent–child | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0507 | Two half second cousins (grandparents are half siblings) | 2 | Exome sequencing |

| FAM0508 | Parent–child | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0509 | Two first cousins once removed (parent's first cousin) | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0510 | Parent–child | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0678 | Two siblings | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM0689 | Uncle–child (via unaffected obligate carrier mother) | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM2006 | Parent–children (two children) | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM2084 | Two second cousins | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM2097 | Two second cousins | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM3679 | Two siblings | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM3727 | Two siblings | 2 | Exome sequencing |

| FAM5673 | Parent–child | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM5737 | Two second cousins | 1 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

| FAM5804 | Parent–child | 2 | CTR9 Sanger sequencing |

WT, Wilms tumour.

The analysis identified only one gene, CTR9, that contained two different disease-segregating PTVs in two of the Wilms tumour families, and no PTVs in the 48 non-Wilms exomes. We identified two different CTR9 PTVs in four individuals from two unrelated families. The mean coverage across the mutations was 70 × and the mutant-read percentage was 50%. We also confirmed the mutations by Sanger sequencing (Table 2, Methods).

Table 2. gDNA and cDNA primer sequences and sizes.

| PCR primer | Forward sequence (5′–3′) | Reverse sequence (5′–3′) | PCR product size (bp) | Multiplex group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exon 1 | GAGCCGTCACTCACCTCTG | AAGGAGGATGCTCTCGCTTC | 235 | A |

| Exon 2 | TGTTGATTATATTCACGAAAAGCAG | GCAGCCAAGCTGGCTATTAC | 276 | B |

| Exon 3 | CTAATCCCTGTGCCAGACAAC | TCCTTGAAATTCACCTGGAG | 856 | C |

| Exon 4 | TCCACCTCCTTCCTATTTGG | TTTGCTGTCTAGCTGAGTTATTAAGG | 308 | A |

| Exon 5 | TGTTCTGTGTTTTCAAGTATTTCTCAC | TCTTTTCATAACTTCATAAGCAACTG | 304 | B |

| Exon 6 | GTTATACTGAGGTTAATTTTGGGG | AGACACATCTGGCTCCAAGAG | 356 | C |

| Exon 7 | GCTTCTAATCCGTTTTAGTGTCTG | AACAAACTCTATAATTTGGAGGGG | 368 | D |

| Exon 8-9 | GAAGAAGATGGAAATGTATCTTACAGG | GAACAAGCTCAGCTAACAAAACTG | 681 | B |

| Exon 10-11 | TGTTAGCTGAGCTTGTTCCAG | TCTGCTTTTGCACGGTCC | 603 | C |

| Exon 12 | CCTAGGGGAGGCTAAGGTAGG | CTGGAGAAATGGGGACATTAG | 441 | A |

| Exon 13 | CCTTTGGGACTTTTCTGTTCC | CAAAACCAGGAAGATGTAGCC | 318 | B |

| Exon 14-15 | CAGTAATCAGCTATTGTGGGAAG | AAACAACTACATTGATCACATTTTAAG | 546 | C |

| Exon 16 | TTGTTTCAAATGAATACTTTCAGAGG | ATGACAGGGCCAGAATGG | 380 | A |

| Exon 17-18 | TTGCAATGCCATTTTGCTAC | GCATTTCAGACAAAATCGGG | 591 | B |

| Exon 19 | GCAAACCTTTTCTCAGACTTTG | CCTCTGTTCCCTACTGTGGC | 262 | C |

| Exon 20 | CACATAGATCAGCTAATGGTCCTG | AATGGCTACCATCCTAAGCAG | 667 | A |

| Exon 21 | CCTCTGCTTAGGATGGTAGCC | CAGAAGGAATTTAACCAATTATCCTC | 317 | B |

| Exon 22 | AATGACAATGGATATGGCCC3′ | GCTTCACTGTTTGGATCAAGTG | 367 | C |

| Exon 23-24 | TATGATTGAGGACAGCACCC | AAGTCTGTCCCCACCCCTC | 689 | E |

| Exon 25 | CCTGTGTAACCACTATTTAGGTCAAG | GGGGCTTAGTAATATACAAACTGATAG | 705 | F |

| cDNA primer | Primer sequence | Partner | Expected PCR product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exon 7F | TGGCAAATCACTTTTTCTTCAA | Exon 11R | 499 |

| Exon 10R | TTTGTGCCAATTCAATCCAA | Exon 8F | 387 |

| Exon 8F | CCCTCCATGCATTCCATAAT | Exon 10R | 387 |

| Exon 11R | AGGATTCGTGTTGCTGTTCC | Exon 7F | 499 |

cDNA, complementary DNA; gDNA, genomic DNA.

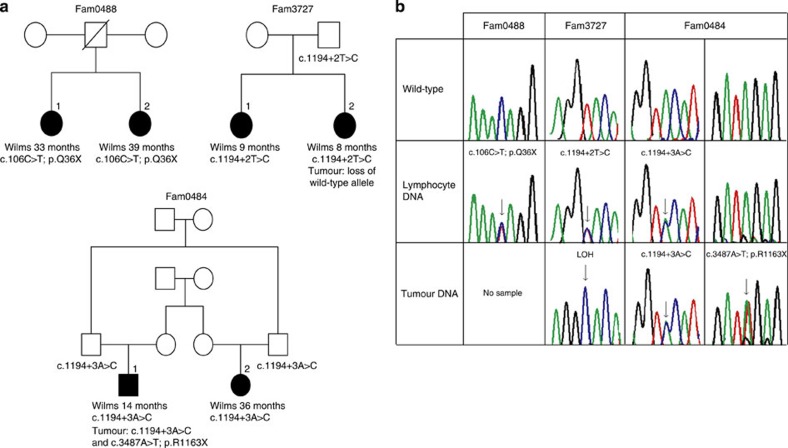

Fam0488 includes two half-sisters who developed Wilms tumour at 33 and 39 months (Fig. 1a, Methods). A heterozygous CTR9 nonsense mutation, c.106C>T; p.Q36X, was present in each half-sister (Fig. 1b). It is assumed that their father was also a mutation carrier, but this cannot be confirmed, as he died before a sample could be obtained.

Figure 1. Germline CTR9 mutations in familial Wilms tumour.

(a) Pedigrees of three Wilms tumour families with germline CTR9 mutations. The age at diagnosis and mutation are shown under the relevant individuals. (b) Sequencing chromatograms showing mutations in blood and tumour DNA and corresponding wild-type sequence from a control.

Fam3727 includes sisters who developed Wilms tumour as infants at 9 and 8 months (Fig. 1a, Methods). A heterozygous essential splice-site mutation c.1194+2T>C was detected in both sisters and was inherited from their unaffected father (Fig. 1b). The mutation is predicted to abolish the exon 9 splice-site, which we confirmed by minigene analysis and complementary DNA (cDNA) sequencing, showing that it results in the deletion of exon 9 (p.320_398del78) (Table 2, Fig. 2a,c, Methods).

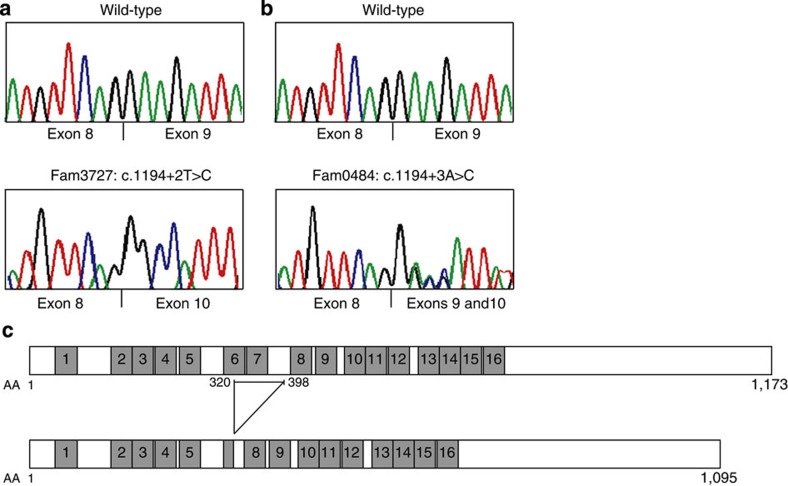

Figure 2. Splicing CTR9 mutations cause in-frame deletion of CTR9 TPR domains.

(a) Sequencing chromatograms from Reverse Transcription-PCR analysis of RNA from HEK293 cells, transiently transfected with CTR9 minigene splicing constructs containing the c.1194+2T>C mutation identified in Fam3727, showing monoallelic deletion of exon 9. (b) cDNA analysis from Fam0484 (proband 2), who is heterozygous for c.1194+3A>C, demonstrates that exon 9 is deleted on one allele. (c) Schematic structures of normal and mutant forms of CTR9 protein showing tetratricopeptide repeat domains (shaded boxes). The c.1194+2T>C and c.1194+3A>C splice-site mutations result in an in-frame deletion of amino acids 320–398 containing two tetratricopeptide repeats.

We next Sanger sequenced the 25 exons and intron–exon boundaries of CTR9 in DNA from 43 individuals with familial Wilms tumour from 29 families (Tables 1 and 2, Methods). We identified another exon 9 splice-site mutation, c.1194+3A>C, in Fam0484, which includes two cousins affected by Wilms tumour at 14 and 36 months (Fig. 1a, Methods). The cousins are related through both parents as their fathers are brothers and their mothers are sisters (Fig. 1a). Both fathers carry the CTR9 splice-site mutation. Analysis of cDNA demonstrated that the mutation results in aberrant splicing and deletion of exon 9, causing the same 78 amino acid deletion detected in Fam3727 (Fig. 2b,c). Thus, in total, our analyses identified CTR9 mutations in three of 35 Wilms tumour families.

Tumour material was available from two individuals. The Wilms tumour from Fam3727, proband 2 showed loss of the wild-type CTR9 allele (Fig. 1b). By contrast, the germline mutation was heterozygous in tumour DNA from Fam0484, proband 1. We therefore sequenced CTR9 in the tumour DNA and identified a somatic truncating mutation, c.3487A>T; p.R1163X (Fig. 1b). While the phase of this mutation in relation to the germline splicing mutation could not be determined, the presence of two mutations in the tumour is consistent with CTR9 being a tumour suppressor gene that requires both alleles to be inactivated for oncogenesis to proceed. It should be noted however that the somatic CTR9 mutation is close to the end of the gene and therefore may not have significant functional impact. It is also noteworthy that only one truncating somatic CTR9 mutation has been reported in 4,745 tumours in which the gene has been analyzed in the COSMIC database ( http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic). Taken together, the available data suggest that the somatic mutation in Fam0484 is not a random passenger event and is likely to be causally related to the development of the Wilms tumour.

To further evaluate the likely pathogenicity of the mutations we had identified, we sequenced CTR9 in 1,000 UK population controls by exome sequencing. No mutation predicted to truncate or alter CTR9 splicing was identified (Table 3, Methods). Furthermore, no CTR9 splicing or truncating mutations have been reported in 8,588 European American or 4,402 African American individuals sequenced through the NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project ( http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/). These data add further evidence for the association of CTR9 mutations with familial Wilms tumour (3/35 versus 0/1,000; P<0.0001). Thus our results provide compelling evidence that CTR9 is a Wilms tumour predisposition gene and strongly suggest it functions as a tumour suppressor gene.

Table 3. Non-pathogenic CTR9 variants identified in Wilms tumour cases and controls.

| Variant | dbSNP |

In-silico predictions |

Consensus splice | Wilms tumour | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PolyPhen-2 | SIFT | |||||

| c.75G>A(p.=) | rs138850547 | No effect | 1 | |||

| c.303G>C; p.Lys101Asn | Possibly damaging | Tolerated | No effect | 1 | ||

| c.304A>G; p.Asn102Asp | Benign | Tolerated | No effect | 1 | ||

| c.762T>C(p.=) | rs116362368 | No effect | 1 | |||

| c.921G>A(p.=) | rs368868162 | No effect | 1 | |||

| c.1233T>C(p.=) | rs143491141 | No effect | 1 | |||

| c.1329G>T; p.Glu443Asp | Benign | Tolerated | No effect | 2 | ||

| c.1461C>T(p.=) | No effect | Common | Common | |||

| c.1494C>T(p.=) | rs7118399 | No effect | Common | Common | ||

| c.1687-3C>T | rs76650154 | No effect | 5 | |||

| c.1800T>C(p.=) | rs199500868 | No effect | 1 | |||

| c.1873-4A>G | No effect | 3 | ||||

| c.2097C>T(p.=) | rs140813178 | No effect | 1 | 8 | ||

| c.2372+4A>C | rs199735513 | No effect | 1 | |||

| c.2445-8T>C | No effect | 1 | ||||

| c.2487C>T(p.=) | No effect | 1 | ||||

| c.2516G>A; p.Arg839Gln | Benign | Tolerated | No effect | 1 | ||

| c.2610G>A(p.=) | No effect | 1 | ||||

| c.2745A>G(p.=) | No effect | 1 | ||||

| c.2897G>C; p.Gly966Ala | rs192522878 | Benign | Tolerated | No effect | 1 | |

| c.2953C>T; p.Arg985Cys | Possibly damaging | Affect protein function | No effect | 1 | ||

| c.3095+8_3095+9dupAT | No effect | 1 | ||||

| c.3149A>G; p.Lys1050Arg | rs141131642 | Benign | Tolerated | No effect | 3 | |

| c.3154T>C; p.Cys1052Arg | rs35696189 | Benign | Tolerated | No effect | 3 | |

| c.3195G>A(p.=) | rs34200650 | No effect | 1 | |||

| c.3211G>A; p.Gly1071Ser | rs35766432 | Benign | Tolerated | No effect | 2 | 2 |

| c.3244G>A; p.Asp1082Asn | rs138871050 | Benign | Tolerated | No effect | 1 | |

| c.3284G>A; p.Arg1095Lys | rs141434094 | Possibly damaging | Tolerated | No effect | 1 | |

| c.3292G>A; p.Gly1098Ser | rs376210239 | Benign | Tolerated | No effect | 1 | |

| c.3402G>A(p.=) | rs147016884 | No effect | 1 | 1 | ||

| c.3449A>G; p.Glu1150Gly | rs35023148 | Benign | Tolerated | No effect | 2 | |

| c.3512A>G; p.Asp1171Gly | Benign | Deleterious | No effect | 1 | ||

dbSNP, database of single nucleotide polymorphisms; PolyPhen-2, polymorphism phenotyping version 2; SIFT, sorting intolerant from tolerant.

Mutations in some cancer predisposition genes contribute appreciably to both familial and non-familial cases, whereas for others the contribution to non-familial cases is small. To evaluate the contribution of CTR9 to non-familial Wilms tumour, we sequenced the coding exons and intron–exon boundaries of the gene in 587 individuals with Wilms tumour and no history of relatives with Wilms tumour. No truncating or splicing mutations were identified. Thirty-two intronic, synonymous or non-synonymous variants were detected, but none are predicted to be pathogenic and the spectrum of variation in Wilms tumour cases was similar to that in the 1,000 population controls. (Table 3). Thus CTR9 mutations appear to be a very rare cause of Wilms tumour, and typically result in familial clustering of the disease.

CTR9 is located at 11p15.3 and encodes a 1,173 amino acid protein. It is widely expressed, including in foetal and adult kidney, and shows evolutionary conservation throughout eukaryotes7,8. CTR9 contains multiple tetratricopeptide repeats (TPR), a versatile protein–protein interaction domain that can act as interaction scaffolds in multi-protein complexes involved in diverse cellular processes9. Two of the three mutations we identified are distinct splicing mutations that result in the same in-frame deletion of exon 9, which includes 78 amino acids and encompasses two of the TPR protein–protein interaction domains. It is tempting to speculate that this mutant protein has specific dysfunction that results in cancer predisposition. However, the third germline mutation generates a stop codon that likely results in a truncated product that lacks all the TPR repeats, or nonsense-mediated RNA decay and haploinsufficiency. Functional analyses to explore the impact of the mutations on CTR9 function will be of interest.

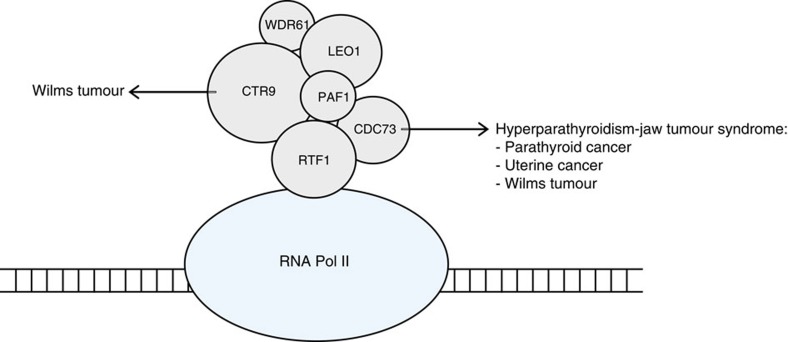

CTR9 is a core component of PAF1c, which has multiple roles in RNA Polymerase II regulation10 (Fig. 3). PAF1c is a multi-protein complex including PAF1, LEO1, CDC73 (also known as parafibromin), CTR9, RTF1 and WDR61 (also known as SKI8). The complex plays important roles in a wide range of biological processes, including the initiation, elongation and termination of gene transcription and transcription-coupled histone modifications such as H2B monoubiquitination and H3K4 and H3K36 methylation7,8. Through these critical regulatory functions, PAF1c influences many essential cellular processes including gene silencing and activation, messenger RNA processing, protein synthesis, DNA repair and cell cycle progression7,8. More recently, PAF1c, particularly CTR9 and RTF1, have been shown to have important roles in organ development during embryogenesis11 and the maintenance of embryonic stem cell identity12.

Figure 3. Schematic scale diagram of PAF1c and RNA Pol II.

PAF1c consists of six subunits: PAF1, LEO1, CDC73, CTR9, RFT1 and WDR61. CTR9 and CDC73 are cancer predisposition genes, mutations in which cause Wilms tumour and hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumour syndrome, respectively. RNA Pol II, RNA polymerase II.

PAF1c has also been implicated in oncogenesis8. Most importantly, CDC73 is a tumour suppressor gene and cancer predisposition gene13,14. Heterozygous inactivating CDC73 mutations have been shown to cause hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumour syndrome (OMIM 145001) and to predispose to cancer13,14. The associated clinical features are variable and include hyperparathyroidism, parathyroid cancer, ossifying fibromas of the jaw, renal abnormalities and uterine tumours. Parathyroid cancer is the most frequent malignant manifestation, and it is estimated that 20–30% of sporadic parathyroid cancers are due to germline CDC73 mutations13. Intriguingly, Wilms tumour is a rare association of CDC73 mutations, having been reported in three individuals, one of whom presented with biallelic Wilms tumour at the exceptionally late age of 53 years2.

The results presented here identify CTR9 as the second PAF1c component that is a cancer predisposition gene. They also further highlight the high heterogeneity of genetic predisposition of Wilms tumour and indicate that additional Wilms tumour predisposition genes must exist. The genes encoding other components of PAF1c: PAF1, LEO1, RTF1 and WDR61, are all highly credible candidate predisposition genes for Wilms tumour and other cancers.

Methods

Patients and samples

The families were recruited through the Factors Associated with Childhood Tumours (FACT) collaboration as detailed in Supplementary Note 1. The study was approved by the UK National Research Ethics Service—London Multicentre Committee (05/MRE02/17) and informed consent was given by all participants, or their parents as appropriate. We included two DNA samples from each of the six families in the exome sequencing experiment. WT1 mutations and 11p15 epigenetic analysis had been performed and were negative. The cases were all non-syndromic, with no evidence of syndromic conditions associated with Wilms tumour such as mosaic variegated aneuploidy or Fanconi anaemia. We also included 43 DNA samples from affected individuals of 29 families (all WT1 and 11p15 negative) and samples from 587 non-familial, unselected Wilms tumour cases, in the CTR9 Sanger sequencing experiment (Table 1). In the CTR9 mutation-positive families we obtained additional samples from relatives and tumour samples, where available. DNA was extracted from whole blood using standard protocols. DNA was extracted from tumour samples using the Phusion Human Specimen Direct PCR Kit (Finnzyme) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Control samples

We used lymphocyte DNA from 1,000 population-based controls obtained from the 1958 Birth Cohort Collection, a continuing follow-up of persons born in the United Kingdom in 1 week in 1958. Biomedical assessment was undertaken during 2002–2004 at which blood samples and informed consent were obtained for the creation of a genetic resource ( http://www.cls.ioe.ac.uk/).

Case reports of CTR9 mutation-positive families

Fam0488 includes two half-sisters with Wilms tumour (Fig. 1a). Proband 1 presented with a right-sided abdominal mass at 33 months and proband 2 presented with a right-sided abdominal mass at 39 months. Both were Wilms tumour, though the histological subtype was not specified. There were no additional clinical features in either child and no family history of childhood cancer. Sequencing of WT1 and epigenetic analyses of 11p15 by Methylation-Specific Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (MS-MLPA) were normal. The children were successfully treated and subsequently lost to follow-up. Their father is presumed to carry the CTR9 mutation. He did not have Wilms tumour and died of a dissecting thoracic aortic aneurysm.

Fam3727 includes two sisters, both diagnosed with Wilms tumour as infants (Fig. 1a). Proband 1 was diagnosed with a triphasic, stromal-predominant, Stage I Wilms tumour of the right kidney at 9 months. She was also found to have a large left ureterocele and a small dysplastic left kidney. Subsequently, while pregnant, she was found to have a unilateral duplicated left ureter. Proband 2 was diagnosed with blastemal-predominant, Stage 1 Wilms tumour of the right kidney at 8 months. There were no syndromic features in either child. Karyotypes were normal, and sequencing of WT1 and epigenetic analyses of 11p15 by MS-MLPA were normal. Both sisters are now adults and remain well.

Fam0484 includes first cousins, a boy and a girl, related through both parents; their fathers are brothers and their mothers are sisters (Fig. 1a). Proband 1 was diagnosed with blastemal-predominant, Stage III Wilms tumour of the left kidney at 14 months. Proband 2 was diagnosed with blastemal-predominant, Stage I Wilms tumour of the left kidney at 36 months. Sequencing of WT1 and epigenetic analyses of 11p15 by MS-MLPA were normal. The cousins are now adults and have remained well.

Exome sequencing

We prepared DNA libraries from 1.5 μg blood-derived genomic DNA using the Paired-End DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Ilumina). DNA was fragmented using Covaris technology and the libraries were prepared without gel size selection. We performed target enrichment using the TruSeq Exome Enrichment Kit (Illumina) by targeting 62 mb of the human genome. The captured DNA libraries were PCR amplified using the supplied paired-end PCR primers. Sequencing was performed with an Illumina HiSeq2000 generating 2 × 101 bp reads.

Exome variant calling

For the Wilms tumour samples, we undertook read mapping and variant analysis using NextGENe software (SoftGenetics) version 2.10 as previously described15,16. We generated 39,660,686–106,571,869 reads per sample, with an average of 59,575,502 reads across the 12 samples. Variants were called using the default NextGENe software mutation calling filters.

For the control samples, we mapped sequencing reads to the human reference genome (hg19) using Stampy version 1.0.14 (ref. 15). Duplicate reads were flagged using Picard version 1.60 ( http://picard.sourceforge.net). Median coverage of the target at 15 × was 91% across the 1,000 individuals, with a median of 47,240,000 reads mapping to the target. Variant calling was performed with Platypus version 0.1.5 (ref. 16).

Exome data analysis

For each family, we first removed all variants, which appeared in only one of the affected individuals in each family, such that only disease-segregating variants were further evaluated. We next utilized the PTV prioritization method6. This is a gene-based strategy that aims to prioritize potential disease-associated genes for follow-up by leveraging two properties of PTVs: (1) the strong association of rare truncating variants with disease, and (2) collapsibility; different PTVs within a gene typically result in the same functional effect and can be equally combined. Specifically, we identified nonsense mutations, coding insertions or deletions that would generate translational frameshifts and insertions, deletions or base substitutions that would disrupt consensus splice residues. We then excluded any gene with more than one PTV in 48 exomes of individuals with other conditions that were sequenced and analyzed in parallel through the same pipelines. This was on the assumption that familial Wilms tumour is a very rare condition, and thus mutations in a Wilms tumour predisposing gene would not be present in unrelated individuals without Wilms tumour. We then stratified the remaining genes according to the number of families that harboured disease-segregating PTVs. We implemented the analyses in the statistical software package R. Scripts are available on request.

CTR9 Sanger sequencing

We screened CTR9 for mutations using Sanger sequencing. Amplifying primers, flanking exons and intron–exon boundaries, were designed using Exon-Primer from the UCSC genome browser ( http://genome.ucsc.edu/). Primer sequences are given in Table 2. PCR reactions were performed in multiplex using the QIAGEN Multiplex PCR Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Amplicons were unidirectionally sequenced using the BigDyeTerminator Cycle sequencing kit and an ABI 3730 automated sequencer (Life Technologies). We analyzed sequencing traces using Mutation Surveyor software (SoftGenetics) and by visual inspection. We confirmed all mutations by bidirectional sequencing from a fresh aliquot of stock DNA. Samples from members of CTR9 mutation-positive families were tested for the family mutation by direct sequencing of the appropriate exon. We also sequenced tumour DNA where available to confirm whether the mutation identified in constitutional DNA was present in the tumour.

In-silico analysis of identified variants

We computed the predicted effects of CTR9 non-synonymous variants on protein function using polymorphism phenotyping version 2 (PolyPhen-2) and sorting intolerant from tolerant (SIFT). All variants (intronic and coding) were also analyzed for their potential effect on splicing. Variants were analyzed using three splice prediction algorithms: NNsplice, MaxEntScan and HumanSplicingFinder. These analyses were performed with Alamut software (Interactive Biosoftware).

cDNA analysis of splice-site mutations

Using genomic DNA from both probands of Fam3727, we amplified the variant and the flanking sequence of interest and inserted the fragment into the multiple cloning sites of vector pcDNA3.1/myc-His(A) (Life Technologies). The vector contains a cytomegalovirus promoter and an ampicillin cassette for selection in bacteria. We used DH5α competent cells for transformation and selected clones for the correct inserts. We purified plasmids containing wild-type CTR9 sequence or the c.1194+2T>C mutation using a QIAprep Spin MiniPrep Kit (QIAGEN) and transfected the products into HEK293 cells using Lipofectamine reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h, we harvested the cells and extracted RNA using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). We also extracted RNA from whole blood provided by proband 2 of Fam0484 using the PAXgene Blood RNA Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In all cases we synthesized cDNA using the ThermoScript RT-PCR System (Life Technologies) with random hexamers and 1 μg of total RNA. We amplified the mutation regions using cDNA-specific primers (Table 2) and sequenced the PCR products as described above.

Author contributions

S.H., E.R.P., S.S., S.S.M., A.M., E.Ra. and S.D.V.D. performed the molecular analyses. E.Ru. and A.E. performed bioinformatics analyses. A.D., H.P., C.S. and K.P.-J. provided samples and data, which was coordinated by A.Z., B.S. and M.W.-P. N.R. designed and oversaw all aspects of the study and wrote the paper with contributions from the other authors.

Additional information

Accession codes: The patient exome sequence data has been deposited in the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA) under the accession code EGAS00001000904. Access to this data is through the ICR Genetic Susceptibility Team data access committee.

How to cite this article: Hanks, S. et al. Germline mutations in the PAF1 complex gene CTR9 predispose to Wilms tumour. Nat. Commun. 5:4398 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5398 (2014).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Note 1

Acknowledgments

We thank the families for their participation in our research and the physicians and nurses that recruited them. Samples were collected through the Factors Associated with Childhood Tumours (FACT) study, which is a Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group (CCLG) Study (the UK National Research Ethics Service Reference: 05/MRE02/17). We are grateful to Darshna Dudakia, Jessie Bull, Rosy Williams, Usha Kini and Judith Kingston for assistance in recruitment. The CCLG receives funding from the UK Department of Health, the National Cancer Intelligence Network, the Scottish Government and Children with Cancer UK. We acknowledge use of services provided by the Institute of Cancer Research Genetics Core Facility, which is managed by Sandra Hanks and Nazneen Rahman. We acknowledge NHS funding to the Royal Marsden/ICR NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. This research was supported by the Wellcome Trust (088804/Z/09/Z), Cancer Research UK (C8620_A9024) and the Institute of Cancer Research, UK.

References

- Pritchard-Jones K. et al. Treatment and outcome of Wilms’ tumour patients: an analysis of all cases registered in the UKW3 trial. Ann. Oncol. 23, 2457–2463 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R. H., Stiller C. A., Walker L. & Rahman N. Syndromes and constitutional chromosomal abnormalities associated with Wilms tumour. J. Med. Genet. 43, 705–715 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman N. et al. Evidence for a familial Wilms' tumour gene (FWT1) on chromosome 17q12-q21. Nat. Genet. 13, 461–463 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J. M. et al. Linkage of familial Wilms' tumor predisposition to chromosome 19 and a two-locus model for the etiology of familial tumors. Cancer Res. 58, 1387–1390 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapley E. A. et al. Evidence for susceptibility genes to familial Wilms tumour in addition to WT1, FWT1 and FWT2. Br. J. Cancer 83, 177–183 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruark E. et al. Mosaic PPM1D mutations are associated with predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer. Nature 493, 406–410 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaehning J. A. The Paf1 complex: platform or player in RNA polymerase II transcription? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1799, 379–388 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomson B. N. & Arndt K. M. The many roles of the conserved eukaryotic Paf1 complex in regulating transcription, histone modifications, and disease states. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1829, 116–126 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan R. K. & Ratajczak T. Versatile TPR domains accommodate different modes of target protein recognition and function. Cell Stress Chaperones 16, 353–367 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller C. L. & Jaehning J. A. Ctr9, Rtf1, and Leo1 are components of the Paf1/RNA polymerase II complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1971–1980 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akanuma T., Koshida S., Kawamura A., Kishimoto Y. & Takada S. Paf1 complex homologues are required for Notch-regulated transcription during somite segmentation. EMBO Rep. 8, 858–863 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L. et al. A genome-scale RNAi screen for Oct4 modulators defines a role of the Paf1 complex for embryonic stem cell identity. Cell Stem Cell 4, 403–415 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpten J. D. et al. HRPT2, encoding parafibromin, is mutated in hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome. Nat. Genet. 32, 676–680 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich T. A. GeneReviews University of Washington (2008) updated 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Lunter G. & Goodson M. Stampy: a statistical algorithm for sensitive and fast mapping of Illumina sequence reads. Genome Res. 21, 936–939 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer A., Phan H., Mathieson I., Zamin I., Twigg S. R. F., WGS500 Consortium, Wilkie A. O. M. & McVean G. Integrating mapping-, assembly- and haplotype-based approaches for calling variants in clinical sequencing applications. Nat. Genet. (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Note 1