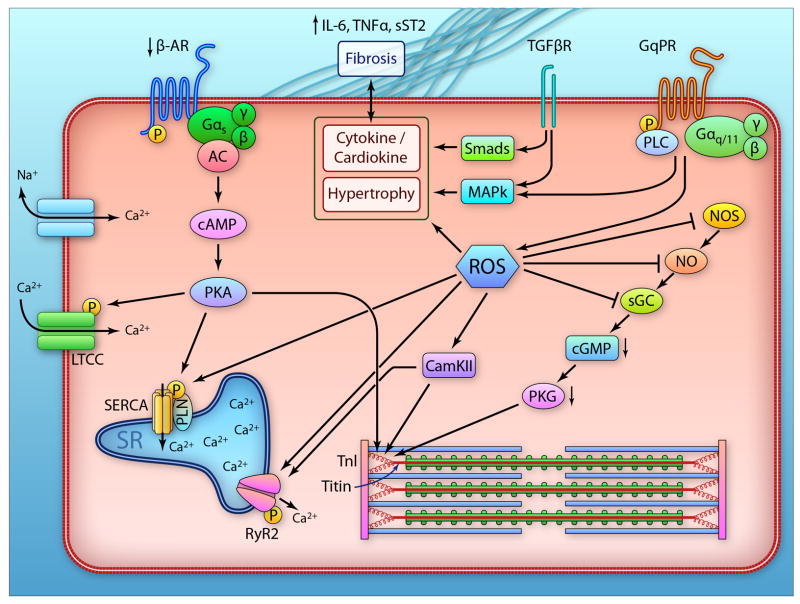

Figure 1.

Schematic of myocardial abnormalties revealed in human HFpEF. The left side shows components of the beta-adrenergic (b-AR) pathway from the receptor to adenylcyclase (AC), generation of cyclic AMP (cAMP) to activation of protein kinase A (PKA). The latter is involved with modification of L-type calcium channels, phospholamban (PLN), titin, and other regulatory thin filament proteins (e.g. troponin I, TnI) which influence myofilament stiffness and contractile activation. Evidence suggests a deficiency in this signaling pathway in HFpEF, with increased titin stiffness and depressed β-AR responsiveness. The middle section shows transforming growth factor b (TGFb) and Gq-protein coupled receptor (GqPR) signaling involving transcription factors (Smad), phospholipase C (PLC) and mitogen activated kinases (MAPk) which are involved with activation of pro-fibrotic and hypertrophic cascades. At the right is the nitric oxide synathase (NOS) pathway resulting in NO activation of soluble guanylatecyclase (sGC), generation of cyclic GMP (cGMP) and activation of protein kinase G (PKG). In the middle is reactive oxygen species (ROS) activated by TGFb, b-AR, and GqPR coupled signaling – which inhibits the NOS-cGMP generation and thereby PKG activity, stimulates CamKII which can render sarcoplasmic reticular (SR) calcium release by the ryanodine receptor (RyR2) more promiscuous. ROS and CamKII also impact titin to influence stiffening. Lastly, the upper right depicts the role of matrix modulation by cytokines/inflammation, and the by-directional interaction of these factors with the myocyte. (Illustration credit: Ben Smith)