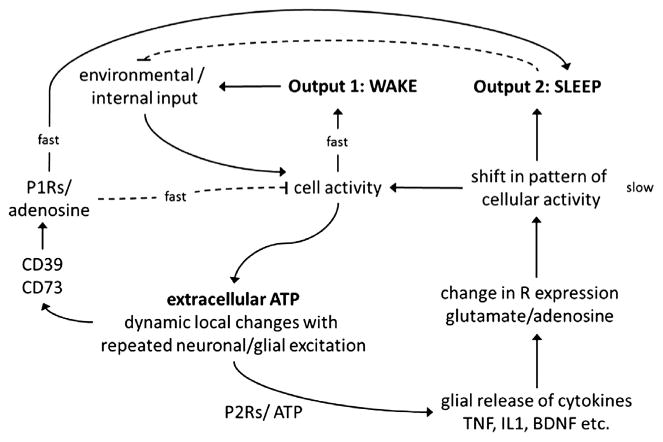

Fig. 1.

The sleep homeostat. Molecular networks operating on different timescales (fast vs slow) comprise the sleep homeostat. Cellular activity is induced and sustained by environmental stimuli. Cellular activity increases arousal (output 1) and causes ATP to be coreleased with glutamate and other neurotransmitters. This extracellular ATP provides a way for the brain to track previous activity; some ATP is enzymatically converted to adenosine (fast) and some binds with glial P2 receptors to facilitate SRS secretion. SRSs induce fast-acting labile substances like adenosine and NO. Alternatively, SRSs and their effectors can lead to alterations (slow) in receptor content and receptor-mediated ion gating, causing a shift in overall cellular activity. Resulting changes in receptor populations predispose affected networks (within the diffusible range of extracellular ATP) to sleep (output 2).