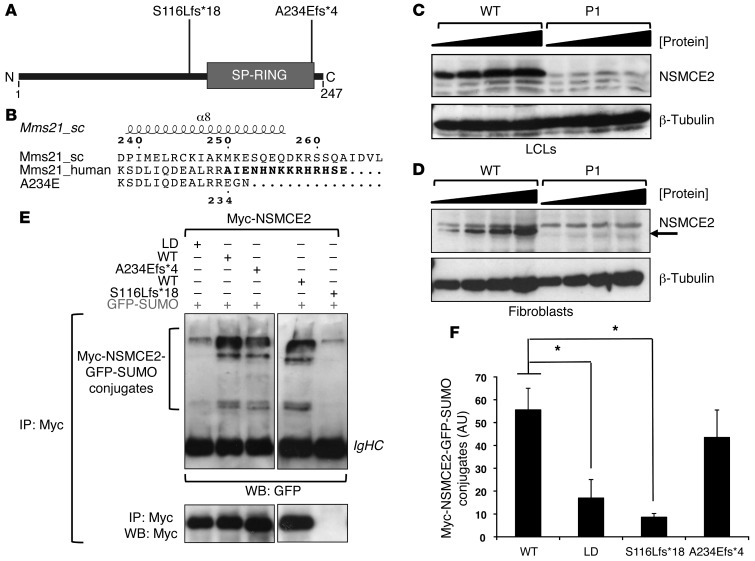

Figure 2. Expression and auto-SUMOylation of NSMCE2/MMS21 frameshift mutations.

(A) Schematic showing positions of patient mutations with respect to the SP-RING SUMO-ligase domain. (B) Schematic of NSMCE2/MMS21 showing disruption of α helix α8 (residues 223–240) by the p.Ala234Glufs*4 mutation. Alignment of human WT (Mms21_human) and p.Ala234Glufs*4 (A234E) MMS21/NSMCE2 based on the crystal structure of S. cerevisiae Mms21 (Mms21_sc; PDB entry: 3HTK; chain C). The 14 amino acids removed by the mutation are marked in boldface. Numbering and secondary structure of S. cerevisiae Mms21 are displayed. The position of the mutation in human MMS21/NSMCE2 is displayed below the sequences. (C) NSMCE2 expression in dermal fibroblasts from P1 assessed using immunoblotting of increasing amounts of whole-cell extract compared with WT fibroblasts. (D) Similar immunoblotting of whole-cell extract from P1 LCLs. (E) Auto-SUMOylation activity of Myc-tagged WT, SUMO LD, and naturally occurring mutant NSMCE2/MMS21 following coexpression with GFP-SUMO1 (upper panels). Auto-SUMOylation was detected following IP using anti-Myc and blotting (WB, Western blot) using anti-GFP antibodies. IgHC, immunoglobulin heavy chain. The lower panel shows relative amounts of immunoprecipitated Myc-NSMCE2. The p.A234Efs*4 mutation appears not to affect protein gel migration under these conditions, unlike p.S116Lfs*18 (Supplemental Figure 3). (F) Quantification of recovered Myc-NSMCE2-GFP-SUMO conjugates by densitometry. Data represent mean ± SD. (n = 3). *P ≤ 0.05 (unpaired, 2-tailed t test).