Abstract

The “Flynn effect” refers to the observed rise in IQ scores over time, resulting in norms obsolescence. Although the Flynn effect is widely accepted, most approaches to estimating it have relied upon “scorecard” approaches that make estimates of its magnitude and error of measurement controversial and prevent determination of factors that moderate the Flynn effect across different IQ tests. We conducted a meta-analysis to determine the magnitude of the Flynn effect with a higher degree of precision, to determine the error of measurement, and to assess the impact of several moderator variables on the mean effect size. Across 285 studies (N = 14,031) since 1951 with administrations of two intelligence tests with different normative bases, the meta-analytic mean was 2.31, 95% CI [1.99, 2.64], standard score points per decade. The mean effect size for 53 comparisons (N = 3,951) (excluding three atypical studies that inflate the estimates) involving modern (since 1972) Stanford-Binet and Wechsler IQ tests (2.93, 95% CI [2.3, 3.5], IQ points per decade) was comparable to previous estimates of about 3 points per decade, but not consistent with the hypothesis that the Flynn effect is diminishing. For modern tests, study sample (larger increases for validation research samples vs. test standardization samples) and order of administration explained unique variance in the Flynn effect, but age and ability level were not significant moderators. These results supported previous estimates of the Flynn effect and its robustness across different age groups, measures, samples, and levels of performance.

Keywords: Flynn effect, IQ test, intellectual disability, capital punishment, special education

Historical Background

The “Flynn effect” refers to the observed rise over time in standardized intelligence test scores, documented by Flynn (1984a) in a study on intelligence quotient (IQ) score gains in the standardization samples of successive versions of Stanford-Binet and Wechsler intelligence tests. Flynn’s study revealed a 13.8-point increase in IQ scores between 1932 and 1978, amounting to a 0.3-point increase per year, or approximately 3 points per decade. More recently, the Flynn effect was supported by calculations of IQ score gains between 1972 and 2006 for different normative versions of the Stanford-Binet (SB), Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), and Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) (Flynn, 2009a). The average increase in IQ scores per year was 0.31, which was consistent with Flynn’s (1984a) earlier findings.

The Flynn effect implies that an individual will likely attain a higher IQ score on an earlier version of a test than on the current version. In fact, a test will overestimate an individual’s IQ score by an average of about 0.3 points per year between the year in which the test was normed and the year in which the test was administered. The ramifications of this effect are especially pertinent to the diagnosis of intellectual disability in high stakes decisions when an IQ cut point is used as a necessary part of the decision-making process. The most dramatic example in the United States is the determination of intellectual disability in capital punishment cases. These determinations in so-called Atkins hearings represent life and death decisions for death row inmates scheduled for execution. Because an inmate may have received several IQ scores with different normative samples over time, whether to acknowledge the Flynn effect is a major bone of contention in the legal system. In addition, the Flynn effect figures in access to services and accommodations, such as determining eligibility for special education and American Disability Act services and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) in the United States.

More generally, conceptions about IQ as a predictor of success in various domains is pervasive in many domains of the behavioral sciences and in Western societies. Many studies use IQ scores as an outcome variable or to characterize the sample. In clinical practice, most assessments routinely administer an IQ test and most applied training programs teach administration and interpretation of IQ test scores. Organizations like MENSA set IQ levels associated with “genius” and people commonly refer to others as “bright” or use more pejorative terms as an indicator of their level of ability. Although the meaningfulness of these uses of IQ scores is beyond the scope of this investigation, they illustrate the pervasiveness of concepts about IQ scores as indicators of individual differences and level of performance.

The Flynn effect is less well known and often not taught in behavioral science training programs (Hagen, Drogin, & Guilmette, 2008). It is important because the normative base of the test directly influences the interpretation of the level of IQ. MENSA, the “high IQ society,” requires an IQ score in the top 2% of the population (www.us.mensa.org/join/testscores/qualifyingscores). The organization accepts scores from a variety of tests, often with no specification of which version of the test. The Stanford-Binet IV and Stanford-Binet 5 are both permitted. If a person applied and took an IQ test in 2014, the required score of 132 on the Stanford-Binet 4 would be equivalent to a score of 126 on the recently normed Stanford-Binet 5 because the normative sample was formed 20 years ago. Although the Flynn effect is not necessarily of general interest to psychology, the pervasive use of IQ test scores in clinical practice and research, in high stakes decisions, and in Western society suggests that it should be. It is not surprising that a PsycINFO® search shows that the number of articles on the Flynn effect rose from 6 in 2001–2002 to 54 in 2010–2011. Most significant is the use of IQ scores in identifying intellectual disabilities and the death penalty, where there are literally hundreds of active cases in the judicial system, and in determining eligibility for social services and special education.

Definition of Intellectual Disability

The identification of an intellectual disability in the United States requires the presence of significant limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior prior to age 18 (American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities [AAIDD], 2010). An IQ score at least two standard deviations below the mean (i.e., ≤ 70) is a common indicator of a significant limitation in intellectual functioning, and captures approximately 2.2% of the population. Although the gold standard AAIDD criteria stress the importance of exercising clinical judgment in the interpretation of IQ scores (e.g., accounting for measurement error), a cut-off score of 70 commonly is used to indicate a significant limitation in intellectual functioning (Greenspan & Switzky, 2006). Thus, were an adult to have attained an IQ score of 73 on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children--Revised (WISC-R) as a child, s/he might not be identified as having a significant limitation in intellectual functioning. However, suppose the WISC-R had been administered in 1992, 20 years after the test was normed. The Flynn effect would have inflated test norms by 0.3 points per year between the year in which the test was normed (1972) and the year in which the test was administered (1992). Correction for that inflation would reduce the person’s IQ score by six points, to 67, thereby indicating a significant limitation in intellectual functioning and highlighting the problems with obsolete norms. Further, the WISC-III, published in 1989, would have been the current edition of the test when the child was tested. This underscores the importance of testing practices (e.g., acquiring and administering the current version of a test) in formal education settings.

High Stakes Decisions

Capital punishment

The Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution prohibits cruel and unusual punishment, and that prohibition informed the Court’s decision in Atkins v. Virginia (2002) to abstain from imposing the death penalty on a defendant with an intellectual disability. In this case, Daryl Atkins, a man determined to have a mild intellectual disability, was convicted of capital murder. The Supreme Court of Virginia initially imposed the death penalty on Atkins; however, the United States Supreme Court reversed the decision due to the presumed difficulty people with intellectual disabilities have in understanding the ramifications of criminal behavior and the emergence of statutes in a growing number of states barring the death penalty for defendants with an intellectual disability.

In 2008, a report indicated that since the reversal of the death penalty in Atkins’ case, 80+ death penalty pronouncements have been converted to life in prison (Blume, 2008). This number has increased significantly since 2008. Importantly, Walker v. True (2005) set a precedent for the consideration of the Flynn effect in capital murder cases. The defendant argued in an appeal that his sentence violated the Eighth Amendment; when corrected for the Flynn effect, his IQ score of 76 on the WISC, administered to the defendant in 1984 when he was 11 years old, would be reduced by four points to 72. He alleged that a score of 72 fell within the range of measurement error recognized by the AAIDD (2010) and the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2000) for a true score of 70. The judges agreed that the Flynn effect and measurement error should be considered in this case. There are hundreds of Atkins hearings involving the Flynn effect in some manner and other issues related to the use of IQ tests (see AtkinsMR/IDdeathpenalty.com)

Special education

Demonstration of an intellectual disability or a learning disability is an eligibility criterion for receipt of special education services in schools. Kanaya, Ceci, and Scullin (2003a) and Kanaya, Scullin, and Ceci (2003b) documented a pattern of “rising and falling” IQ scores in children diagnosed with an intellectual disability or learning disability as a function of the release date of the new version of an intelligence test. One study (Kanaya et al., 2003a) mapped IQ scores obtained from children’s initial special education assessments between 1972 and 1977, during the transition from the WISC to the WISC-R, and between 1990 and 1995, during the transition from the WISC-R to the WISC-III. The authors reported a reduction in IQ scores during the fourth year of each interval (one year after the release of the new test version) followed by an increase in IQ scores during subsequent years. In a second study (Kanaya et al., 2003b), the authors reported a 5.6-point reduction in IQ score for children initially tested with the WISC-R and subsequently tested with the WISC-III, with a significantly greater proportion of these children being diagnosed with an intellectual disability during the second assessment than children who completed the same version of the WISC during both assessments. More recent studies have supported these patterns in children assessed for learning disabilities with the WISC-III (Kanaya & Ceci, 2012).

Taken together, these studies suggest that the use of obsolete norms leads to inflation of the IQ scores of children referred for a special education assessment as a function of the time between the year in which the test was normed and the year in which the test was administered. The use of a test with obsolete norms reduces the likelihood of a child being identified with an intellectual disability and receiving appropriate services, and may increase the prevalence of learning disabilities; the inflated IQ score helps produce a discrepancy between intellectual functioning and achievement, which in education settings has often been interpreted as indicating a learning disability (Fletcher et al., 2007). These studies also highlight the importance of using the current version of a test in education settings, a practice which may be thwarted by a school district’s budgetary constraints and challenges associated with learning the administration and scoring procedures for the new test (Kanaya & Ceci, 2007).

Social security disability

As with determination of the death penalty and eligibility for special education, IQ testing remains an important component of the decision-making process for determining eligibility for SSDI as a person with an intellectual disability. Like the AAIDD, the Social Security Administration (2008) requires significant limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior for a diagnosis of intellectual disability; however, these limitations must be present prior to age 22. Moreover, individuals with an IQ at or below 59 are eligible de facto for SSDI, whereas those with an IQ between 60 and 70 must demonstrate work-related functional limitations resulting from a physical or other mental impairment, or two other specified functional limitations (e.g., social functioning deficits). The manual, like the AAIDD manual, explicitly discusses the importance of correcting for the Flynn effect, but acknowledges that precise estimates are not available.

Flynn’s Work

Flynn’s (1984a) landmark study, which revealed increasing IQ at a median rate of 0.31 points per year between 1932 and 1978 across 18 comparisons of the SB, WAIS, WISC, and Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI), was the first analysis of its kind. Seventy-three studies totaling 7,431 participants provided support for this effect. Whereas Flynn’s (1984a) study focused on comparisons documented in publication manuals of primarily the first editions of the Stanford-Binet and Wechsler tests, a second study investigated IQ gains in 14 developed countries using a variety of instruments, including Ravens Progressive Matrices, Wechsler, and Otis-Lennon tests (Flynn, 1987). IQ gains amounted to a median of 15 points in one generation, described by Flynn (1987) as “massive.” An extension of Flynn’s (1984a) work documented a mean rate of IQ gain equaling approximately 0.31 IQ points per year across 12 comparisons of the SB, WAIS, and WISC standardization samples (Flynn, 2007), a value highly consistent with earlier findings. Further, 14 comparisons of Stanford-Binet and Wechsler standardization samples, accounting for the recent publication of the WAIS-IV, revealed an annual rate of IQ gain equaling 0.31 (Flynn, 2009a). These latter findings, based on the simple averaging of IQ gains across studies, were supported by the only meta-analysis addressing the Flynn effect (Fletcher, Stuebing, & Hughes, 2010). For these 14 studies, Fletcher et al. (2010) calculated a weighted mean rate of IQ gain of 2.80 points per decade, 95% CI [2.50, 3.09], and a weighted mean rate of IQ gain of 2.86, 95% CI [2.50, 3.22], after excluding comparisons that included the WAIS-III because effect sizes produced by comparisons between the WAIS-III and another test differed considerably from the effect sizes produced by comparisons between other tests. The puzzling effects produced by comparisons including the WAIS-III were consistent with Flynn’s (2006a) study, wherein he demonstrated that IQ score inflation on the WAIS-III was reduced because of differences in the range of possible scores at the lower end of the distribution.

Other notable investigations conducted by Flynn include the computation of a weighted average IQ gain per year of 0.29 between the WISC and WISC-R across 29 studies comprising 1,607 subjects (1985): a rate of IQ gain per year of 0.31 between the WISC-R and the WISC-III across test manual studies and a selection of studies carried out by independent researchers (1998a); and a rate of IQ gain per year of 0.20 between the WAIS-R and WAIS-III across test manual studies (1998a). Prior to these studies, Flynn (1984b) also reported SB gains across standardization samples, and both real and simulated gains for the WPPSI and the first two versions of the WISC and WAIS. Flynn (1988b) noted consistent gains between the WISC (N = 93) and WISC-R (N = 296) in Scottish children (1990); for the Matrices and Instructions tests in an Israeli military sample totaling approximately 26,000 subjects per year between 1971 and 1984; between the WISC-III and an earlier version of the test in samples from the United States, West Germany, Austria, and Scotland totaling 3,190 subjects (2000); and for the Coloured Progressive Matrices in British standardization samples totaling 1,833 participants (2009b). The existence of the Flynn effect is rarely disputed. However, a working magnitude and measurement error associated with the Flynn effect are not well established, leaving unanswerable the question of how much of a correction – if any – to apply to IQ test scores to account for the norming date of the test. Further, there is considerable contention over factors that may cause the Flynn effect (Flynn, 2007, 2012; Neisser, 1998).

Proposed Causes of the Flynn Effect

There are multiple hypotheses about the basis for the Flynn effect, including genetic and environmental factors, and measurement issues.

Genetic hypotheses

Mingroni (2007) hypothesized that IQ gains are the result of increasingly random mating, termed heterosis (or hybrid vigor), a phenomenon that produces changes in traits governed by the combination of dominant and recessive alleles. However, Lynn (2009) noted that the Flynn effect in Europe has mirrored the effect in the United States despite evidence of minimal migration to Europe prior to 1950 and limited inter-mating between native and immigrant populations since then. A more comprehensive argument against a genetic cause for the Flynn effect has been made by Woodley (2011).

Environmental factors

Woodley (2011) argued that “The [Flynn] effect only concerns the non-g variance unique to specific cognitive abilities” (p. 691), presumably bringing environmental explanations for the Flynn effect to the forefront. Environmental factors hypothesized as moderators of the Flynn effect include sibship size (Sundet, Borren, & Tambs, 2008) and pre-natal and early post-natal nutrition (Lynn, 2009). In Norway, Sundet et al. demonstrated that an increase in IQ scores paralleled a decrease in sibship size, with the greatest increase in IQ scores occurring between cohorts with the greatest decrease in sibship size. For example, between birth cohort 1938–1940 and 1950–1952, the percentage of sibships composed of 6+ children decreased from 20% to 5%, and IQ score increased by 6 points.

With rates of Development Quotient score gains in infants mirroring IQ score gains of preschool children, school-aged children, and adults, Lynn (2009) questioned the validity of explanations whose effects would emerge later in development, such as improvements in child rearing (Elley, 1969) and education (Tuddenham, 1948); increased environmental complexity (Schooler, 1998), test sophistication (Tuddenham, 1948), and test-taking confidence (Brand, 1987); and the effects of genetics (Jensen, 1998) and the individual and social multiplier phenomena (Dickens & Flynn, 2001a; Dickens & Flynn, 2001b). Lynn (2009) proposed improvements in pre- and post-natal nutrition as likely causes of the Flynn effect, citing a parallel increase in infants of other nutrition-related characteristics, including height, weight, and head circumference. Improvement to the prenatal environment is also supported by trends in the reduction of alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy (Bhuvaneswar, Chang, Epstein, & Stern, 2007; Tong, Jones, Dietz, D’Angelo, & Bombard, 2009).

Neisser (1998) suggested that increasing IQ scores have mirrored socioenvironmental changes in developing countries. If IQ test score changes are a product of socioenvironmental improvements, then as living conditions optimize, IQ scores should plateau. This suggestion has been echoed by Sundet, Barlaug, and Torjussen (2004), who documented a plateau in IQ scores in Norway (Sundet et al., 2004) and speculated that changes in family life factors (e.g., family size, parenting style, and child care) might be partly responsible for this pattern. A decline in IQ scores has even been noted in Denmark (Teasdale & Owen, 2008; Teasdale & Owen, 2005), a pattern that the authors suggested might be due to a shift in educational priorities toward more practical skills manifest in the increasing popularity of vocational programs for post-secondary education.

Although Flynn (2010) acknowledged that his “scientific spectacles” hypothesis may no longer explain current IQ gains, he maintained that there was a period of time when it was the foremost contributor. Putting on “scientific spectacles” refers to the tendency of contemporary test takers to engage in formal operational thinking, as evidenced by a massive gain of 24 IQ points on the Similarities subtest of the WISC, a measure of abstract reasoning, between 1947 and 2002, a gain unparalleled by any other subtest (Flynn & Weiss, 2007). Conceptualizing IQ gains as a shift in thinking style from concrete operational to formal operational rather than an increase in intelligence per se would explain why previous generations thrived despite producing norms on IQ tests that overestimated the intellectual abilities of future generations (Flynn, 2007). However, this difference may be more simply attributed to changes across different versions of Similarities and other verbal subtests (Kaufman, 2010) of the WISC. Nonetheless, Dickinson and Hiscock (2010) reported a Flynn effect for WAIS Similarities of 4.5 IQ points per decade for WAIS to WAIS-R and 2.6 IQ points per decade for WAIS-R to WAIS-III. The average was 3.6 IQ points per decade or 0.36 IQ points per year. This change in adult performance is only moderately less than Flynn’s 0.45 points per year for the WISC between 1947 and 2002.

Measurement issues

Tests of verbal ability, compared with performance-based measures, have been reported to be less sensitive to the Flynn effect (Flynn, 1987; Flynn, 1994; Flynn, 1998b; Flynn, 1999), which may be related to changes in verbal subtests. Beaujean and Osterlind (2008) and Beaujean and Sheng (2010) used Item Response Theory (IRT) to determine whether increases in IQ scores over time reflect changes in the measurement of intellectual functioning rather than changes in the underlying construct, i.e., the latent variable of cognitive ability. Although changes in Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised scores were negligible (Beaujean & Osterlind, 2008), it is a verbal test that differs in many respects from Wechsler and Stanford-Binet tests. Wicherts et al. (2004) found that intelligence measures were not factorially invariant, such that the measures displayed differential patterns of gains and losses that were unexpected given each test’s common factor means. Taken together, these studies suggest that increases in IQ scores over time may be at least partly a result of changes in the measurement of intellectual functioning. Moreover, Dickinson and Hiscock (2010) reported that published norms for age-related changes in verbal and performance subtests do not take into account the Flynn effect. In comparisons of subtest scores from the WAIS-R and WAIS-III in 20-year-old and 70-year-old cohorts, the Flynn-corrected difference in Verbal IQ between 20-year-olds and 70-yearolds was 8.0 IQ points favoring the 70-year-olds (equivalent to 0.16 IQ points per year). In contrast, the younger group outscored the older group in Performance IQ by a margin of 9.5 IQ points (equivalent to 0.19 IQ points per year). These findings suggested that apparent age-related declines in Verbal IQ between the ages of 20 and 70 years are largely artifacts of the Flynn effect and that, even though age-related declines in Performance IQ are real declines, the magnitudes of those declines are amplified substantially by the Flynn effect.

Some studies have examined intercorrelations among subtests of IQ measures to determine the variance in IQ scores explained by g, with preliminary evidence suggesting that IQ gains have been associated with declines in measurement of g (Kane & Oakland, 2000; Te Nijenhuis & van der Flier, 2007). Flynn (2007), on the other hand, has discounted the association between g and increasing IQ scores, and a dissociation between g and the Flynn effects has been claimed by Rushton (2000). However, Raven’s Progressive Matrices, renowned for its g-loading, has demonstrated a rate of IQ gain of 7 points per decade, more than double the rate of the Flynn effect as manifested on WAIS, SB, and other multifactorial intellectual tests (Neisser, 1997).

What is Rising?

The theories highlighted above offer explanations for the Flynn effect but leave an important question unanswered: What exactly does the Flynn effect capture (i.e., what is rising)? Although much of the previous research on the Flynn effect has focused on the rise of mean IQ scores over time, studies distinguishing rates of gain among elements of IQ tests more readily answer the question of what is rising. Relative to scores produced by verbal tests, there have been greater gains in scores produced by nonverbal, performance-based measures like Raven’s Progressive Matrices (Neisser, 1997) and Wechsler performance subtests (Dickinson & Hiscock, 2011; Flynn, 1999). These types of tests are strongly associated with fluid intelligence, suggesting less of a rise in crystalized intelligence that reflects the influence of education, such as vocabulary. A notable exception is the increasing scores produced by the Wechsler verbal subtest Similarities (Flynn, 2007; Flynn & Weiss, 2007), although this subtest taps into elements of reasoning not required by the other subtests comprising the Wechsler Verbal IQ composite.

Dickens and Flynn (2001b) provided a framework for understanding the rise in more fluid versus crystallized cognitive abilities. They identified social multipliers as elements of the sociocultural milieu that contributed to rising IQ scores among successive cohorts of individuals. Flynn (2006b) highlighted two possible sociocultural contributions to the Flynn effect, one related to patterns of formal education and the other to the influence of science. Specifically, years of formal education increased in the years prior to World War II, whereas priorities in formal education shifted from rote learning to problem solving in the years following World War II. As time continued to pass, the value placed on problem solving in the workplace and leisure time spent on cognitively engaging activities continued to exert an effect on skills assessed by nonverbal, performance-based measures. The second sociocultural contributor, science, refers to the simultaneous rise in the influence of scientific reasoning and the abstract thinking and categorization required to perform well on nonverbal, performance-based measures.

The Current Study

The primary objective of this meta-analysis was to determine whether the Flynn effect could be replicated and more precisely estimated across a wide range of individually administered, multifactorial intelligence tests used at different ages and levels of performance. Answers to these research questions will assist in determining the confidence with which a correction for the Flynn effect can be applied across a variety of intelligence tests, ages, ability levels, and samples. By completing the meta-analysis, we also hoped to provide evidence evaluative of existing explanations for the Flynn effect, thus contributing to theory.

With the exceptions of the Flynn (1984a, 2009a) and Flynn and Weiss (2007) analyses of gains in IQ scores across successive versions of the Stanford-Binet and Wechsler intelligence tests, most research comparing IQ test scores has focused on correlations between two tests and/or average mean difference between two successive versions of the same test. This study will expand the literature on estimates of the Flynn effect by computing more precisely the magnitude of the effect over multiple versions of several widely-used, individually administered, multifactorial intelligence tests, viz., Kaufman, Stanford-Binet, and Wechsler tests and versions of the Differential Ability Scales, McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities, and the Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities. The data for these computations were obtained from validity studies conducted by test publishers or independent research teams. In addition to providing more precise weighted meta-analytic means, meta-analysis allows estimates of the standard error and evaluation of potential moderators.

This study deliberately focused on sources of heterogeneity (i.e., moderators) that could be readily identified through meta-analytic searches and that helped explain variability in estimates of the magnitude of the Flynn effect. Investigation of these moderators is needed to advance understanding of variables that might limit or promote confidence in applying a correction for the Flynn effect in high stakes decisions. Here the IQ tests that are used are variable in terms of test and normative basis, with the primary focus on the composite score. The tests are given to a broad age range and to people who vary in ability. It is not clear that the standard Flynn effect estimate can be applied among individuals of all ability levels and ages who took any of a number of individually-administered, multifactorial tests. In addition, there may be special circumstances related to test administration setting that might influence the numerical value of the Flynn effect. If the selected moderators (i.e., ability level, age, IQ tests administered, test administration setting, and test administration order) influence the estimate of the Flynn effect, the varying estimates will contribute to the tenability of the theories offered above for the existence and meaning of the Flynn effect.

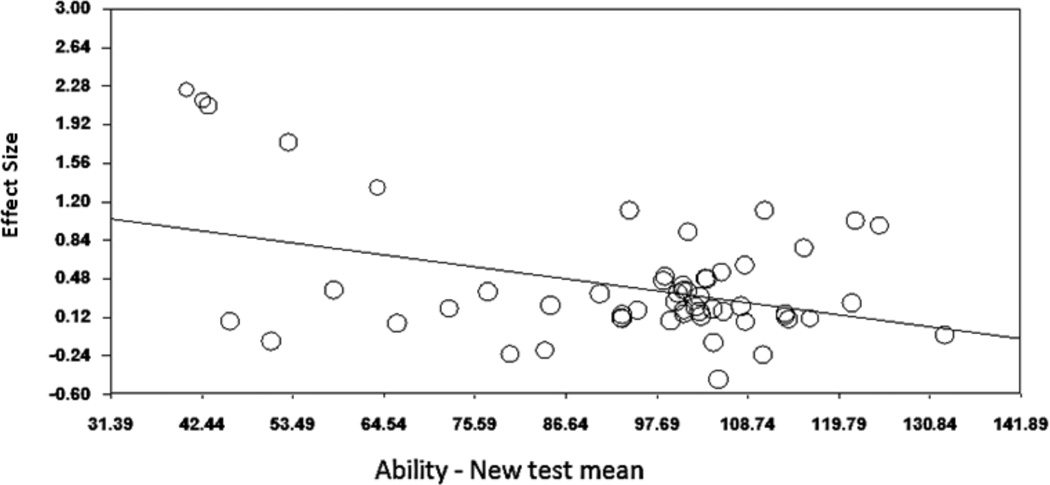

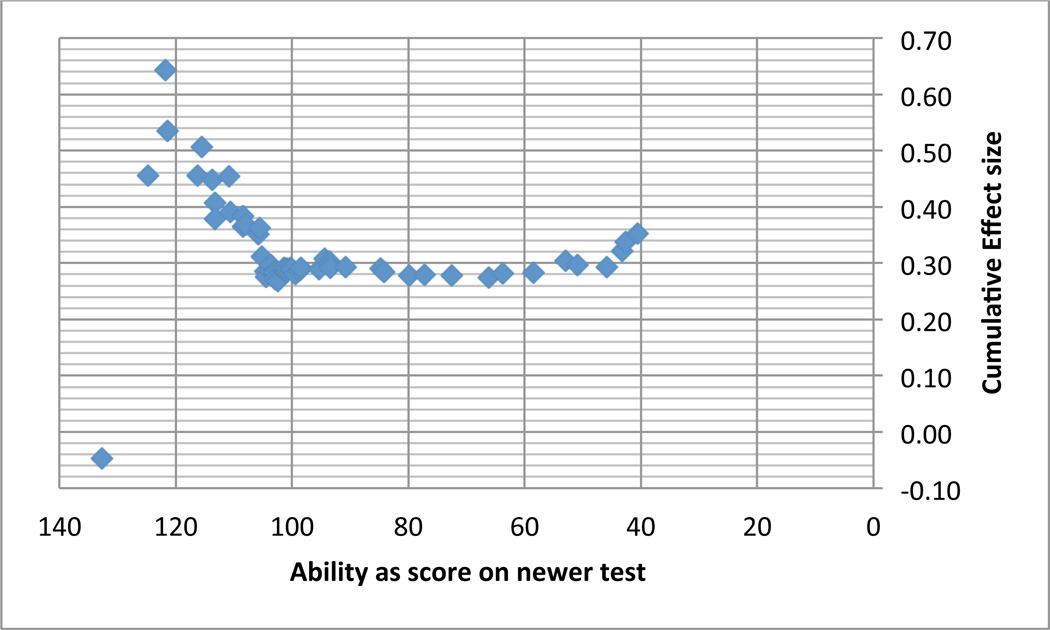

The evidence for influences of these moderators is mixed, with no clear directions. Recent evidence has suggested that middle and lower ability groups (IQ = 79–109) demonstrate the customary 0.31–0.37-point increase per year, whereas higher ability groups (IQ = 110+) demonstrate a minimal increase of 0.06–0.15 points per year (Zhou, Zhu, Weiss, & Pearson, 2010). Whereas some previous studies have supported this finding (e.g., Lynn & Hampson, 1986; Teasdale & Owen, 1989), others have not. Two studies found the opposite pattern (Graf & Hinton, 1994; Sanborn, Truscott, Phelps, & McDougal, 2003), and one study indicated smaller gains at intelligence levels both above and below average, with the highest gains evident in people at the lowest end of the ability spectrum (Spitz, 1989). Little research has been conducted to investigate the relation between age and gains in IQ score. Cross-sectional research has indicated no difference among young children, older children, and adults (Flynn, 1984b) and no difference among adult cohorts ranging in age from 35–80 years (Ronnlund & Nilsson, 2008).

Research on the Flynn effect has focused almost exclusively on the effect produced from administrations of the Stanford-Binet and Wechsler tests. This study expanded the scope by including a wider range of individually administered, largely multifactorial intelligence tests. Comparisons of older and more recently normed versions of the Stanford-Binet and Wechsler tests were conducted to facilitate comparisons with previous work and help determine if the Flynn effect has remained constant over time.

Another potential moderator pertains to study sample. Study data were collected by test publishers or independent researchers for validation purposes, or by mental health professionals for clinical decision-making purposes. Validation studies conducted by test publishers likely employed the most rigorous procedures with regard to sampling, selection of administrators, and adherence to administration and scoring protocols. However, the more homogenous samples examined in the research and clinical studies (e.g., children suspected of having an intellectual disability or juvenile delinquents) may produce results that are more generalizable to specific populations and permit comparison of Flynn effect values across those special populations.

Another set of moderators involves measurement issues, such as changes in subtest configuration and order effects. These issues were addressed by Kaufman (2010), who pointed out that changes in the instructions and content of specific Wechsler subtests (e.g., Similarities) could make comparing older and newer versions akin to comparing apples and oranges. However, other research has shown that estimates of the size of the Flynn effect based on changes in subtest scores yield values similar to estimates from the composite scores (Agbayani & Hiscock, 2013; Dickinson & Hiscock, 2010). Kaufman’s concern related to interpretations of the basis of the Flynn effect and not to its existence, and we did not pursue this question because it has been addressed in other studies (Dickinson & Hiscock, 2011). Subtest coding of a larger corpus of tests was difficult because the data were often not available. However, Kaufman also suggested that the Flynn effect could be the result of prior exposure when taking the newer version of an IQ test first and then transferring a learned response style to the older IQ test, thus receiving higher scores when the older test is given second. In order for order effects to occur, the interval between the administration of the new and old tests would have to be short enough for the examinee to demonstrate learning, which is often the case in studies comparing different versions of an IQ test, the basis for determination of the Flynn effect.

Although the Flynn effect has been well documented during the 20th century, the meta-analytic method used during the current study is a novel approach to documenting this phenomenon. The method of the current study aligns with a key research proposal identified by Rodgers (1999) as important in advancing our understanding of the Flynn effect; viz., a formal meta-analysis. Although many of Rodgers’ (1999) proposals have since been implemented, there remains room for understanding the meaning of the Flynn effect, how the Flynn effect is reflected in batteries of tests over time, and how the Flynn effect manifests itself across subsamples defined by ability level or other characteristics.

Method

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies identified from test manuals or peer-reviewed journals were included if they reported sample size and mean IQ score for each test administered; these variables were required for computation of the meta-analytic mean. All English-speaking participant populations from the United States and the United Kingdom were included. Variations in study design were acceptable. Administration of both tests must have occurred within one year of one another. Studies could have been conducted at any point prior to the completion date of the literature search in 2010.

We limited our primary investigation to comparisons between tests with greater than five years between norming periods, which is consistent with Flynn’s (2009) work. The rationale for this decision was that any difference in IQ scores from a short interval, even seemingly insignificant ones, would be magnified when converted to a value per decade (see Flynn, 2012). As a secondary analysis, we expanded our investigation to all comparisons between tests with at least one year between norming periods to assess whether our decision to limit our investigation to comparisons between tests with greater than five years between norming periods affected the results of the meta-analysis. We did not include comparisons between tests with one year or less between norming periods since years between norming periods served as the denominator of our effect size. A value of zero, representing no difference in years between norming periods, produced an error in the effect size estimate. Finally, we did not include single construct tests, such as the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test or the Test of Nonverbal Intelligence. There may be other multifactorial tests to consider, but the 27 we chose represent the major IQ tests in use over the past few decades.

Search Strategies

Twenty-seven intelligence test manuals for multifactorial measures were obtained, one for each version of the Differential Ability Scales (Elliot, 1990; Elliot, 2007), Kaufman Adolescent and Adult Intelligence Test (Kaufman & Kaufman, 1993), Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children (Kaufman & Kaufman, 1983; Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004a), Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990; Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004b), McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities (McCarthy, 1972), Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (Roid, 2003; Terman & Merrill, 1937; Terman & Merrill, 1960; Terman & Merrill, 1973; Thorndike, Hagen, & Sattler, 1986), Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1999), Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Wechsler, 1955; Wechsler, 1981; Wechsler, 1997; Wechsler, 2008), Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (Wechsler, 1949; Wechsler, 1974; Wechsler, 1991; Wechsler, 2003), Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1967; Wechsler, 1989; Wechsler, 2002), and Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Ability (Woodcock & Johnson, 1977; Woodcock & Johnson, 1989; Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001).

Also, a systematic literature review was completed using PsycINFO®, crossing the keywords comparison, correlation, and validity with the full and abbreviated titles of the measures. The first author reviewed each study in full unless abstract review determined the study was not relevant (e.g., some test validation studies included comparisons between tests not under consideration in this meta-analysis). A formal search for unpublished studies was not undertaken; it was presumed that the results of test validation studies would provide important information irrespective of the findings and would therefore constitute publishable data.

Coding Procedures

The first author, who had prior training and experience in coding studies for meta-analyses, coded all of the studies in the current meta-analysis. Two undergraduate volunteers were trained by the first author, and each volunteer coded half the studies. Agreement between the first author and the volunteers on each variable was calculated for blocks of ten studies. These estimates ranged from 90.5–99.1% per block, with an average agreement of 95.8% per block. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, during which the first author and volunteers referred to the original article. Discrepancies were commonly the result of a coder typo or failure of a coder to locate a particular value in an article.

Moderator Analyses

Moderators included ability level, age, test set, order of administration, and sample. Ability level was coded as the sample’s score on the most recently normed test, and age was coded as the sample’s age in months. Each comparison was assigned to a test set, as follows. First, due to Flynn’s focus on the Stanford-Binet and Wechsler tests, these tests were grouped together and were further separated into an old set and a modern set. The old set included comparisons of only Wechsler and Stanford-Binet tests normed before 1972, with the modern set representing versions normed since 1972. The latter set aligned with comparisons published in Flynn and Weiss (2007) and Flynn (2009). If a modern test was compared to an old test, the comparison was coded old. The Differential Ability Scales, Kaufman Adolescent and Adult Intelligence Test, and Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities were grouped together as non-Wechsler/Binet tests with modern standardization samples. The Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test and the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence were grouped together as screening tests. The Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children was separately analyzed due to its grounding in Luria’s model of information processing that addressed differences in simultaneous and sequential processing. Fourteen effects remained from the original set of 285 after sorting effects into these groupings. All of these comparisons contained the McCarthy Scales, but with multiple old and modern tests.

Order of administration was included as a moderator variable. Tests were frequently counterbalanced so that approximately half of the sample got each test first. However, in a substantial number of the studies, one test was uniformly given first. We coded these by the percentage of examinees given the old test first: 100 means that 100% of the examinees got the old test first; 0 means that all examinees got the new test first; 50 means that the tests were counterbalanced. In 7 of these effects, a different value was reported and these were rounded to 0, 0.50 or 100. For example, 14% (given the old test first) was rounded to 0, and 94% was rounded to 100.

Each comparison was also grouped by study sample. Standardization studies were completed during standardization and were reported in test manuals. Research studies appeared in peer-reviewed journals and examined comparisons among a small selection of intelligence tests. Clinical studies reported results from assessments completed of clinical samples, including determination of special education needs.

Statistical Methods

Effect size metric

Comprehensive Meta Analysis software (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2005) was used for the core set of analyses. Specifically, we employed the module that requires input of an effect size and its variance for each study. Effects were coded as the difference between the old test mean and the new test mean. Positive effects reflect a positive Flynn effect with the score on the old test higher than the score on the new test despite being taken by the same individuals at approximately the same time. The effect size calculated from each study was the raw difference between the mean score on the old and new tests divided by the number of years between the norming dates of the two tests. This metric is directly interpretable as the estimated magnitude of the Flynn effect per year. Since the scales used by all of the tests were virtually the same (M = 100, SD = 15 or 16), no further standardization (such as dividing by population standard deviation [SD]) was required (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009). The actual SD for each test was used in computing the variance of the effects.

Effect size weighting

The variance for each effect is required for computation of the weight given to each effect in the overall analysis. The weight is the inverse of the variance, so studies with the smallest variance are given the most weight. Small variance (high precision) for an effect is achieved via (a) large Ns, (b) high reliabilities for both tests and high content overlap between tests which are jointly reflected in the correlation between the tests, and (c) long intervals between the norming periods of the two tests. The formula (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009) used for the variance of typical pretest-posttest effects in meta-analysis is:

| (1) |

Where SD2New is the variance of the more recently normed test, SD2Old is the variance of the less recently normed test, r is the reported correlation between the two tests, and N is the total sample size. In the numerator, actual reported correlations were used when available. For 54 of the 285 studies, no correlation was reported. In these cases, if there were other studies that compared the same two tests, the correlations from the other studies were converted to Fisher’s z. These were then averaged and converted back to a correlation and used in place of the missing value. If no other studies compared the same two tests, the mean correlation for the entire set of studies was computed and substituted in for the missing value. This occurred for two study results. The mean correlation for each pair of tests was also retained and used in a parallel analysis to determine the impact of using the sample-specific correlation rather than a population correlation in the estimator of the effect variance.

To allow for the differential precision in effects due to the years between norming periods of the two tests being compared, we adapted a formula from Raudenbush and Xiao-Feng (2001) that allows calculation of the change in variance as a function of the change in duration in years of the period between the norming of the two tests, holding number of time points constant. Using D to represent a duration of 1 year, D’ to represent a different duration, either longer or shorter, and ω=D’/D to represent the factor of increase or decrease from one year, then the proportion of the variances is equal to:

| (2) |

In other words, the variance (V’) for an effect with a 5 year duration between norming periods will be 1/25th the size of the variance (V) of an effect with a one year duration between norming periods, all other things being equal. Thus, the variance we entered into the CMA software for each effect size was:

| (3) |

The numerator of the above formula is the variance of the difference between the two tests being compared. The denominator adjusts this variance by the sample size (N) and by the duration in years of the period between the norming of the two tests.

Credibility intervals

In a random effects model, the true variance of effects is estimated. The standard deviation of this distribution is represented by Tau [τ]. Tau is used to form a credibility interval around the mean effect, capturing 95% of the distribution of true effects by extending out 1.96τ from the mean in both positive and negative directions. The credibility interval acknowledges that there is a distribution of true effects rather than one true effect. In interpreting the credibility interval, it is helpful to consider width as well as location. Even a distribution of true effects that is centered near 0 (where the mean effect might not be significant) may contain many members that might be meaningfully large in either direction. Moderator analysis may be used to try to find subsets of effects within this distribution, to narrow the uncertainty about how large the effect might be in a given situation; however, in the case of true random effects, each causal variable might explain a very small portion of the variance and moderator analysis might not improve prediction substantially.

Selection of random effects model

A random effects analytic model was employed because the studies were not strict replications of each other, in which case it would make sense to expect a single underlying fixed effect. Rather, the studies varied in multiple ways, each of which was expected to have some impact on the observed Flynn effect. These factors include, but are not limited to (a) the specific test pair being compared, (b) the unique population being tested, (c) the age of the sample (which was not always reported quantitatively), (d) the interval between the presentation of the old and new test, (e) the order of presentation of the tests, (f) unusual administration practices (e.g., Spruill, 1988), and (g) interactions among these factors. The result of these multiple causes is a distribution of true effects, rather than a single effect.

In a random effects model, the mean effect is ultimately interpreted as the mean of a distribution of true population effects. Additionally, in a random effects model, the variance of the effects has two variance components. One is due to the true variance in population effects and the second is due to sampling variance around the population mean effect. The result is that the weight given each study is a function of both within-study precision due to sample size and between-study variability. Sample size thus has less effect in the precision of each study. Large sample size studies are given less weight than they would have been in a fixed effects study, and studies with smaller samples are given more weight (Borenstein et al., 2009).

Heterogeneity in effect sizes

Heterogeneity describes the degree to which effect sizes vary between studies. The Q statistic is employed to capture the significance of this variance and is calculated by summing the squared differences between individual study effect sizes and the mean effect size. It is distributed as a chi-square statistic with k-1 degrees of freedom, where k is the number of studies. In addition, I2 is employed to capture the extent to which detected heterogeneity is due not to chance but to true, identifiable variation between studies. I2 is calculated:

| (4) |

and once multiplied by 100 is directly interpretable as the proportion of variance due to true heterogeneity.

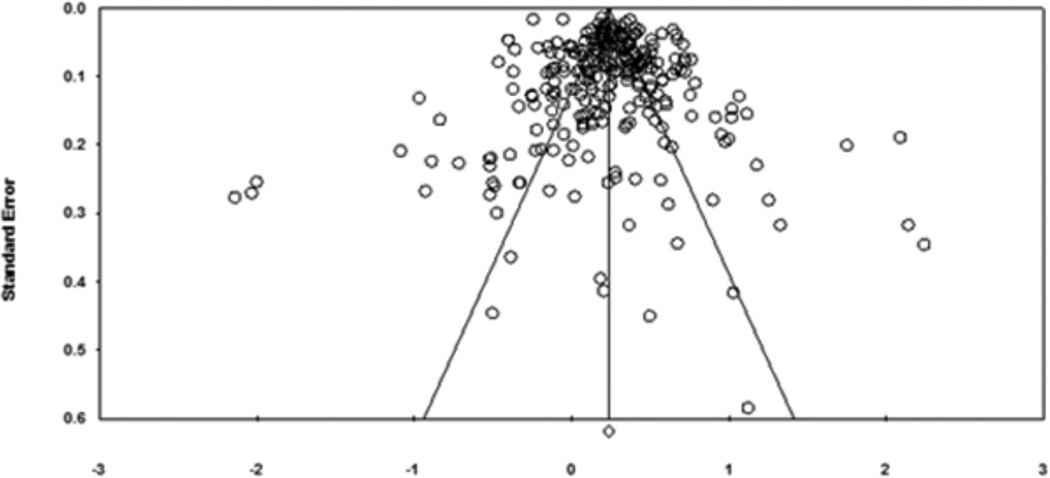

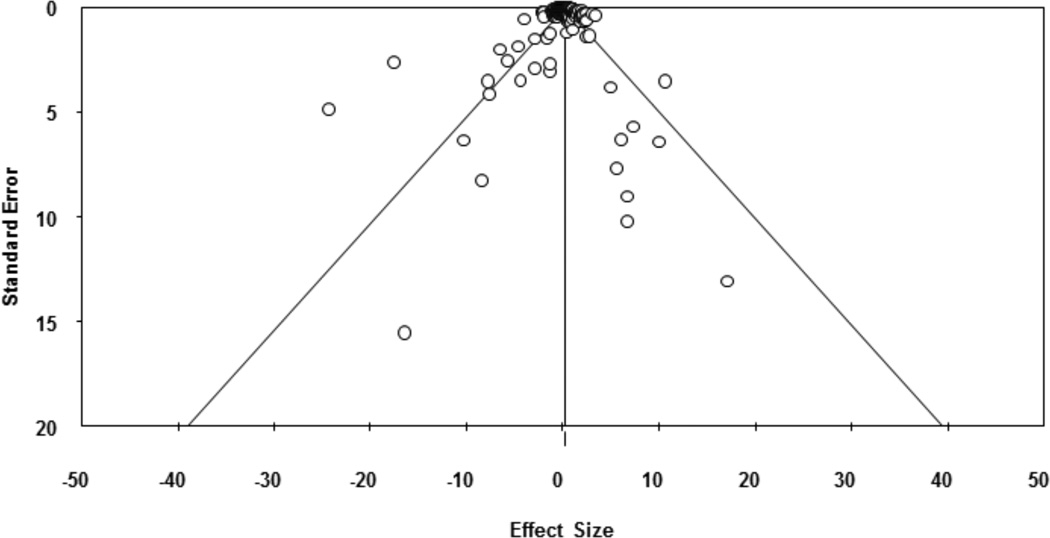

Publication bias

We did not expect to find evidence for publication bias in this meta-analysis. The descriptive data collected from each study in the form of sample sizes, means, and correlations between tests is not typically the type of data that is subject to tests of significance and thus would not be a direct cause of failure to publish due to non-significance. Additionally, many of the effects were gleaned from the technical manuals of the tests being compared where no publication bias is expected. However, we did evaluate the distributions of effects within each portion of our analysis via funnel plots.

Results

Citations

The literature review produced a total of 4,383 articles. This total does not reflect unique articles, since each article would often appear in multiple keyword searches. One hundred and fifty-four empirical studies and 27 test manuals met inclusion criteria, from which 378 comparisons were extracted, 285 of which were normed more than 5 years apart. The chronological range of the Flynn effect data collected was from 1951 upon publication of Weider, Noller, and Schramm’s (1951) comparison study of the WISC and SB to 2010, the year in which the literature review was completed. Table 1 shows the effect size produced by each of the 378 comparisons and includes information pertaining to sample size and age in months.

Table 1.

Sample Size, Sample Age, Tests Administered, and Effect Sizes by Study

| Source | N | Agea | Newer Test | Older Test | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modern ≥ 5b | ||||||

| 1 | Bower & Hayes, 1995 | 26 | 132.88 | SB4c | SB 72d | 0.08 |

| 2 | Carvajal & Weyand, 1986 | 23 | 109.5 | SB4 | WISC-Re | 0.13 |

| 3 | Carvajal et al., 1987 | 32 | 227 | SB4 | WAIS-Rf | 0.37 |

| 4 | Clark et al., 1987 | 47 | 63 | SB4 | SB 72 | 0.07 |

| 5 | Doll & Boren, 1993 | 24 | 114 | WISC-IIIg | WISC-R | 0.35 |

| 6 | Gordon et al., 2010 | 17 | 194 | WISC-IVh | WAIS-IIIi | 1.75 |

| 7 | Gunter et al., 1995 | 16 | 132 | WISC-III | WISC-R | −0.19 |

| 8 | Krohn & Lamp, 1989 | 89 | 59 | SB4 | SB 72 | 0.11 |

| 9 | Lamp & Krohn, 2001 | 89 | 59 | SB4 | SB 72 | 0.10 |

| 10 | Nelson & Dacey, 1999 | 42 | 248.04 | SB4 | WAIS-R | 2.09 |

| 11 | Quereshi & Seitz, 1994 | 72 | 75.1 | WPPSI-Rj | WISC-R | 0.34 |

| 12 | Quereshi et al., 1989 | 36 | 197.9 | WAIS-R | WISC-R | 0.1 |

| 13 | Quereshi et al., 1989 | 36 | 197.9 | WAIS-R | WISC-R | 1.11 |

| 14 | Quereshi et al., 1989 | 36 | 197.05 | WAIS-R | WISC-R | 0.18 |

| 15 | Quereshi et al., 1989 | 36 | 197.05 | WAIS-R | WISC-R | 1.11 |

| 16 | Robinson & Nagle, 1992 | 75 | 111 | SB4 | WISC-R | 0.25 |

| 17 | Robinson et al., 1990 | 28 | 30 | SB4 | SB 72 | 0.97 |

| 18 | Roid, 2003 | 87 | 744 | SB5k | WAIS-III | 0.91 |

| 19 | Roid, 2003 | 66 | 132 | SB5 | WISC-III | 0.41 |

| 20 | Roid, 2003 | 71 | 48 | SB5 | WPPSI-R | −0.46 |

| 21 | Roid, 2003 | 104 | 108 | SB5 | SB4 | 0.22 |

| 22 | Roid, 2003 | 80 | 84 | SB5 | SB L-Ml | 0.12 |

| 23 | Rothlisberg, 1987 | 32 | 93.19 | SB4 | WISC-R | 0.53 |

| 24 | Sabatino & Spangler, 1995 | 51 | 163.2 | WISC-III | WISC-R | −0.04 |

| 25 | Sandoval et al., 1988 | 30 | 197.5 | WAIS-R | WISC-R | 0.18 |

| 26 | Sevier & Bain, 1994 | 35 | 110 | WISC-III | WISC-R | 0.76 |

| 27 | Spruill, 1991 | 32 | ․ | SB4 | WAIS-R | 2.24 |

| 28 | Spruill, 1991 | 38 | ․ | SB4 | WAIS-R | 2.14 |

| 29 | Thompson & Sota, 1998 | 23 | 196 | WISC-III | WAIS-R | 0.60 |

| 30 | Thompson & Sota, 1998 | 23 | 196 | WISC-III | WAIS-R | −0.23 |

| 31 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 21 | 234 | SB4 | WAIS-R | 1.32 |

| 32 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 47 | 233 | SB4 | WAIS-R | 0.5 |

| 33 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 205 | 113 | SB4 | WISC-R | 0.21 |

| 34 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 19 | 155 | SB4 | WISC-R | 0.10 |

| 35 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 90 | 132 | SB4 | WISC-R | 0.23 |

| 36 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 61 | 167 | SB4 | WISC-R | 0.06 |

| 37 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 139 | 83 | SB4 | SB 72 | 0.17 |

| 38 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 82 | 88 | SB4 | SB 72 | 1.01 |

| 39 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 14 | 100 | SB4 | SB 72 | −0.22 |

| 40 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 22 | 143 | SB4 | SB 72 | −0.10 |

| 41 | Urbina & Clayton, 1991 | 50 | 79 | WPPSI-R | WISC-R | 0.48 |

| 42 | Wechsler, 1981 | 80 | 192 | WAIS-R | WISC-R | 0.15 |

| 43 | Wechsler, 1989 | 50 | 79 | WPPSI-R | WISC-R | 0.47 |

| 44 | Wechsler, 1991 | 189 | 192 | WISC-III | WAIS-R | 0.36 |

| 45 | Wechsler, 1991 | 206 | 132 | WISC-III | WISC-R | 0.31 |

| 46 | Wechsler, 1997 | 184 | 192 | WAIS-III | WISC-III | −0.11 |

| 47 | Wechsler, 1997 | 24 | 219.6 | WAIS-III | WISC-R | 0.33 |

| 48 | Wechsler, 1997 | 26 | 343.2 | WAIS-III | SB4 | 0.15 |

| 49 | Wechsler, 1997 | 192 | 522 | WAIS-III | WAIS-R | 0.17 |

| 50 | Wechsler, 1997 | 88 | 583.2 | WAIS-III | WAIS-R | 0.14 |

| 51 | Wechsler, 2002 | 176 | 60 | WPPSI-IIIm | WPPSI-R | 0.08 |

| 52 | Wechsler, 2003 | 183 | 192 | WISC-IV | WAIS-III | 0.45 |

| 53 | Wechsler, 2003 | 233 | 132 | WISC-IV | WISC-III | 0.19 |

| 54 | Wechsler, 2008 | 238 | 632.4 | WAIS-IVn | WAIS-III | 0.26 |

| 55 | Wechsler, 2008 | 24 | 386.4 | WAIS-IV | WAIS-III | 0.37 |

| 56 | Wechsler, 2008 | 24 | 348 | WAIS-IV | WAIS-III | 0.2 |

| Other ≥ 5o | ||||||

| 57 | Appelbaum & Tuma, 1977 | 20 | 121 | WISC-R | WISCp | 0.07 |

| 58 | Appelbaum & Tuma, 1977 | 20 | 120 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.15 |

| 59 | Arinoldo, 1982 | 20 | 57 | MSCAq | WPPSIr | 0.20 |

| 60 | Arnold & Wagner, 1955 | 50 | 102 | WISC | SB 32s | 0.07 |

| 61 | Axelrod & Naugle, 1998 | 200 | 519.6 | KBITt | WAIS-R | −0.4 |

| 62 | Barratt & Baumgarten, 1957 | 30 | 126 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.58 |

| 63 | Barratt & Baumgarten, 1957 | 30 | 126 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.08 |

| 64 | Bradway & Thompson, 1962 | 111 | 354 | WAISu | SB 32 | 0.66 |

| 65 | Brengelmann & Renny, 1961 | 75 | 442.92 | WAIS | SB 32 | −0.35 |

| 66 | Brooks, 1977 | 30 | 96 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.29 |

| 67 | Brooks, 1977 | 30 | 96 | SB 72 | WISC | 0.37 |

| 68 | Byrd & Buckhalt, 1991 | 46 | 149 | DASv | WISC-R | 0.12 |

| 69 | Carvajal et al., 1988 | 21 | 69 | SB4 | MSCA | −0.1 |

| 70 | Carvajal et al., 1988 | 20 | 66 | SB4 | WPPSI | 0.05 |

| 71 | Chelune et al., 1987 | 43 | 576 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.40 |

| 72 | Cohen & Collier, 1952 | 51 | 89 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.32 |

| 73 | Covin, 1977 | 30 | 102 | WISC-R | WISC | −0.00 |

| 74 | Craft & Kronenberger, 1979 | 15 | 196.44 | WISC-R | WAIS | 0.72 |

| 75 | Craft & Kronenberger, 1979 | 15 | 196.8 | WISC-R | WAIS | 0.54 |

| 76 | Davis, 1975 | 53 | 69 | MSCA | SB 60w | 0.57 |

| 77 | Edwards & Klein, 1984 | 19 | 451.2 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.13 |

| 78 | Edwards & Klein, 1984 | 19 | 451.2 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.37 |

| 79 | Eisenstein & Engelhart, 1997 | 64 | 500.4 | KBIT | WAIS-R | −0.25 |

| 80 | Elliot, 1990 | 23 | 54 | WPPSI-R | K-ABCx | 0.5 |

| 81 | Elliot, 1990 | 49 | 41.5 | DAS | MSCA | 0.42 |

| 82 | Elliot, 1990 | 40 | 42.5 | DAS | MSCA | 0.45 |

| 83 | Elliot, 1990 | 66 | 110 | DAS | WISC-R | 0.50 |

| 84 | Elliot, 1990 | 60 | 180 | DAS | WISC-R | 0.35 |

| 85 | Elliot, 1990 | 23 | 54 | DAS | K-ABC | 0.67 |

| 86 | Elliot, 1990 | 27 | 72 | DAS | K-ABC | 1.25 |

| 87 | Faust & Hollingsworth, 1991 | 33 | 53.9 | WPPSI-R | MSCA | 0.07 |

| 88 | Field & Sisley, 1986 | 17 | 360 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.22 |

| 89 | Field & Sisley, 1986 | 25 | 360 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.25 |

| 90 | Fourqurean, 1987 | 42 | 116 | K-ABC | WISC-R | −0.71 |

| 91 | Frandsen & Higginson, 1951 | 54 | 116 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.21 |

| 92 | Gehman & Matyas, 1956 | 60 | 182 | WISC | SB 32 | −0.10 |

| 93 | Gehman & Matyas, 1956 | 60 | 133 | WISC | SB 32 | −0.12 |

| 94 | Gerken & Hodapp, 1992 | 16 | 54 | WPPSI-R | SB 60 | 0.08 |

| 95 | Giannell & Freeburne, 1963 | 38 | 218.88 | WAIS | SB 32 | 0.55 |

| 96 | Giannell & Freeburne, 1963 | 36 | 219.96 | WAIS | SB 32 | 0.50 |

| 97 | Giannell & Freeburne, 1963 | 35 | 224.28 | WAIS | SB 32 | 0.35 |

| 98 | Hamm et al., 1976 | 22 | 121.68 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.32 |

| 99 | Hamm et al., 1976 | 26 | 153.73 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.29 |

| 100 | Hannon & Kicklighter, 1970 | 13 | 192 | WAIS | WISC | −0.04 |

| 101 | Hannon & Kicklighter, 1970 | 13 | 192 | WAIS | WISC | −2.03 |

| 102 | Hannon & Kicklighter, 1970 | 32 | 192 | WAIS | WISC | 0.95 |

| 103 | Hannon & Kicklighter, 1970 | 33 | 192 | WAIS | WISC | −0.50 |

| 104 | Hannon & Kicklighter, 1970 | 11 | 192 | WAIS | WISC | 1.12 |

| 105 | Hannon & Kicklighter, 1970 | 18 | 192 | WAIS | WISC | 1.03 |

| 106 | Harrington et al., 1992 | 10 | 48 | WPPSI-R | WJTCAy | −0.66 |

| 107 | Harrington et al., 1992 | 10 | 60 | WPPSI-R | WJTCA | −0.16 |

| 108 | Hartlage & Boone, 1977 | 42 | 126 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.20 |

| 109 | Hartwig et al., 1987 | 30 | 135.6 | SB4 | SB 60 | −0.05 |

| 110 | Hays et al., 2002 | 85 | 408 | WASI | KBIT | 0.22 |

| 111 | Holland, 1953 | 23 | ․ | WISC | SB 32 | 0.10 |

| 112 | Holland, 1953 | 29 | ․ | WISC | SB 32 | 0.10 |

| 113 | Jones, 1962 | 80 | 96 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.54 |

| 114 | Jones, 1962 | 80 | 108 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.46 |

| 115 | Jones, 1962 | 80 | 120 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.38 |

| 116 | Kangas & Bradway, 1971 | 48 | 498 | SB 60 | WAIS | −2 |

| 117 | Kaplan et al., 1991 | 30 | 57 | WPPSI-R | WPPSI | 0.36 |

| 118 | Karr et al., 1992 | 21 | 69 | SB4 | MSCA | −0.17 |

| 119 | Karr et al., 1993 | 32 | 63.6 | WPPSI-R | MSCA | 0.07 |

| 120 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990 | 64 | 257 | KBIT | WAIS-R | −0.11 |

| 121 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990 | 41 | 66 | KBIT | K-ABC | −0.13 |

| 122 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990 | 35 | 128 | KBIT | WISC-R | 0.35 |

| 123 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990 | 70 | 100 | KBIT | K-ABC | 0.07 |

| 124 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990 | 39 | 136 | KBIT | K-ABC | −0.48 |

| 125 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 1993 | 118 | 156 | KAIT | WISC-R | 0.23 |

| 126 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 1993 | 71 | 208.8 | KAIT | WAIS-R | 0.14 |

| 127 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 1993 | 108 | 312 | KAIT | WAIS-R | 0.21 |

| 128 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 1993 | 90 | 494.4 | KAIT | WAIS-R | 0.47 |

| 129 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 1993 | 74 | 747.6 | KAIT | WAIS-R | 0.25 |

| 130 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 1993 | 124 | 135.6 | KAIT | K-ABC | 0.47 |

| 131 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004b | 54 | 68 | KBIT-IIz | K-BIT | 0.10 |

| 132 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004a | 48 | 120 | K-ABC-IIaa | K-ABC | 0.30 |

| 133 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004a | 119 | 126 | K-ABC-II | WISC-III | 0.09 |

| 134 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004a | 29 | 174 | K-ABC-II | KAITbb | 0.13 |

| 135 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004b | 53 | 135 | KBIT-II | K-BIT | 0.24 |

| 136 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004b | 74 | 383 | KBIT-II | K-BIT | 0.16 |

| 137 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004b | 43 | 122 | KBIT-II | WISC-III | 0.24 |

| 138 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004b | 67 | 384 | KBIT-II | WAIS-III | 0.78 |

| 139 | King & Smith, 1972 | 24 | 72 | WPPSI | WISC | −0.15 |

| 140 | King & Smith, 1972 | 24 | 72 | SB 60 | WISC | −0.51 |

| 141 | Klanderman et al., 1985 | 41 | 102 | K-ABC | SB 72 | 0.56 |

| 142 | Klanderman et al., 1985 | 41 | 102 | K-ABC | WISC-R | 0.40 |

| 143 | Klinge et al., 1976 | 16 | 169.32 | WISC-R | WISC | −0.12 |

| 144 | Klinge et al., 1976 | 16 | 169.32 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.40 |

| 145 | Krohn et al., 1988 | 38 | 51 | K-ABC | SB 72 | −0.32 |

| 146 | Krohn & Lamp, 1989 | 89 | 59 | K-ABC | SB 72 | −0.12 |

| 147 | Krugman et al., 1951 | 38 | 60 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.72 |

| 148 | Krugman et al., 1951 | 20 | 174 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.24 |

| 149 | Krugman et al., 1951 | 38 | 72 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.64 |

| 150 | Krugman et al., 1951 | 43 | 84 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.25 |

| 151 | Krugman et al., 1951 | 44 | 96 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.39 |

| 152 | Krugman et al., 1951 | 31 | 108 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.66 |

| 153 | Krugman et al., 1951 | 29 | 120 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.36 |

| 154 | Krugman et al., 1951 | 37 | 132 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.42 |

| 155 | Krugman et al., 1951 | 22 | 144 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.42 |

| 156 | Krugman et al., 1951 | 30 | 156 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.42 |

| 157 | Kureth et al., 1952 | 50 | 60 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.72 |

| 158 | Kureth et al., 1952 | 50 | 72 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.36 |

| 159 | Lamp & Krohn, 2001 | 89 | 59 | K-ABC | SB 72 | −0.11 |

| 160 | Larrabee & Holroyd, 1976 | 24 | 129 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.25 |

| 161 | Larrabee & Holroyd, 1976 | 14 | 129 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.50 |

| 162 | Levinson, 1959 | 57 | 65.54 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.76 |

| 163 | Levinson, 1959 | 60 | 66.65 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.66 |

| 164 | Levinson, 1960 | 117 | 66.1 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.71 |

| 165 | Lippold & Claiborn, 1983 | 30 | 619.56 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.34 |

| 166 | McCarthy, 1972 | 35 | 75 | MSCA | SB 60 | 1.02 |

| 167 | McCarthy, 1972 | 35 | 75 | MSCA | WPPSI | 0.36 |

| 168 | McGinley, 1981 | 12 | 141 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.17 |

| 169 | McGinley, 1981 | 9 | 141 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.37 |

| 170 | McKerracher & Scott, 1966 | 31 | 384 | SB 60 | WAIS | 0.64 |

| 171 | Milrod & Rescorla, 1991 | 50 | 59 | WPPSI-R | WPPSI | 0.38 |

| 172 | Milrod & Rescorla, 1991 | 30 | 59 | WPPSI-R | WPPSI | 0.05 |

| 173 | Mishra & Brown, 1983 | 88 | 359.76 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.19 |

| 174 | Mitchell et al., 1986 | 35 | ․ | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.15 |

| 175 | Munford, 1978 | 10 | 141 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.04 |

| 176 | Munford, 1978 | 10 | 141 | WISC-R | WISC | −0.36 |

| 177 | Munford & Munoz, 1980 | 11 | 150.5 | WISC-R | WISC | −0.07 |

| 178 | Munford & Munoz, 1980 | 9 | 150.5 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.34 |

| 179 | Nagle & Lazarus, 1979 | 30 | 197.5 | WISC-R | WAIS | 0.69 |

| 180 | Naglieri, 1984 | 35 | 105 | K-ABC | WISC-R | −0.92 |

| 181 | Naglieri, 1984 | 33 | 105 | K-ABC | WISC-R | 0.59 |

| 182 | Naglieri, 1985 | 37 | 117 | K-ABC | WISC-R | −0.83 |

| 183 | Naglieri, 1985 | 51 | 91 | K-ABC | MSCA | −0.11 |

| 184 | Naglieri & Jensen, 1987 | 86 | 128.4 | K-ABC | WISC-R | 0.43 |

| 185 | Naglieri & Jensen, 1987 | 86 | 129.6 | K-ABC | WISC-R | 0.08 |

| 186 | Naugle et al., 1993 | 200 | 519.6 | KBIT | WAIS-R | −0.39 |

| 187 | Oakland et al., 1971 | 24 | 72 | SB 60 | WISC | −0.52 |

| 188 | Oakland et al., 1971 | 24 | 74 | WPPSI | WISC | 0.21 |

| 189 | Oakland et al., 1971 | 24 | 72 | WPPSI | WISC | −0.15 |

| 190 | Oakland et al., 1971 | 24 | 74 | SB 60 | WISC | 0.02 |

| 191 | Obrzut et al., 1984 | 19 | 110.06 | K-ABC | WISC-R | 0.28 |

| 192 | Obrzut et al., 1984 | 13 | 111.06 | K-ABC | WISC-R | −0.47 |

| 193 | Obrzut et al., 1987 | 29 | 114.96 | K-ABC | SB 72 | −0.38 |

| 194 | Obrzut et al., 1987 | 29 | 114.96 | K-ABC | WISC-R | −0.88 |

| 195 | Phelps et al., 1993 | 40 | 108 | WISC-III | K-ABC | 1.00 |

| 196 | Phillips et al., 1978 | 60 | 73.92 | MSCA | WPPSI | 1.17 |

| 197 | Pommer, 1986 | 56 | 87.86 | K-ABC | WISC-R | −1.08 |

| 198 | Prewett, 1992 | 40 | 189 | KBIT | WISC-R | 0.02 |

| 199 | Prifitera & Ryan, 1983 | 32 | 529.08 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.31 |

| 200 | Quereshi, 1968 | 124 | 180.1 | WAIS | WISC | 0.6 |

| 201 | Quereshi & Miller, 1970 | 72 | 208.65 | WAIS | WISC | 0.49 |

| 202 | Quereshi & McIntire, 1984 | 24 | 74.5 | WPPSI | WISC | 0 |

| 203 | Quereshi & McIntire, 1984 | 24 | 74.5 | WPPSI | WISC | 0.50 |

| 204 | Quereshi & McIntire, 1984 | 24 | 74.5 | WPSSI | WISC | 0.16 |

| 205 | Quereshi & McIntire, 1984 | 24 | 74.5 | WISC-R | WISC | −0.14 |

| 206 | Quereshi & McIntire, 1984 | 24 | 74.5 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.25 |

| 207 | Quereshi & McIntire, 1984 | 24 | 74.5 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.18 |

| 208 | Quereshi & McIntire, 1984 | 24 | 74.5 | WISC-R | WPPSI | −0.49 |

| 209 | Quereshi & McIntire, 1984 | 24 | 74.5 | WISC-R | WPPSI | −0.33 |

| 210 | Quereshi & McIntire, 1984 | 24 | 74.5 | WISC-R | WPPSI | 0.23 |

| 211 | Quereshi & Ostrowski, 1985 | 72 | 230.9 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.15 |

| 212 | Quereshi & Erstad, 1990 | 36 | 891.6 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.64 |

| 213 | Quereshi & Erstad, 1990 | 36 | 891.6 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.43 |

| 214 | Quereshi & Erstad, 1990 | 18 | 1032 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.67 |

| 215 | Quereshi & Erstad, 1990 | 27 | 906 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.57 |

| 216 | Quereshi & Erstad, 1990 | 27 | 786 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.41 |

| 217 | Quereshi & Seitz, 1994 | 72 | 75.1 | WPPSI-R | WPPSI | 0.40 |

| 218 | Quereshi & Seitz, 1994 | 72 | 75.1 | WISC-R | WPPSI | 0.53 |

| 219 | Rabourn, 1983 | 52 | 308.4 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.27 |

| 220 | Reilly et al., 1985 | 26 | 84 | WJTCA | MSCA | −0.05 |

| 221 | Reynolds & Hartlage, 1979 | 66 | 152.4 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.18 |

| 222 | Rohrs & Haworth, 1962 | 46 | 149.88 | SB 60 | WISC | −0.33 |

| 223 | Ross & Morledge, 1967 | 30 | 192 | WAIS | WISC | −0.36 |

| 224 | Rowe, 1977 | 20 | 170.5 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.016 |

| 225 | Rowe, 1977 | 24 | 170.5 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.34 |

| 226 | Rust & Yates, 1997 | 67 | 102 | WISC-III | K-ABC | 0.01 |

| 227 | Schwarting, 1976 | 58 | 126 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.30 |

| 228 | Sewell, 1977 | 35 | 62.29 | SB 72 | WPPSI | 0.61 |

| 229 | Shahim, 1992 | 40 | 74.4 | WISC-R | WPPSI | −0.22 |

| 230 | Sherrets & Quattrocchi, 1979 | 13 | 141.6 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.05 |

| 231 | Sherrets & Quattrocchi, 1979 | 15 | 141.6 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.20 |

| 232 | Simon & Clopton, 1984 | 29 | 354 | WAIS-R | WAIS | −0.08 |

| 233 | Simpson, 1970 | 120 | 192 | WAIS | WISC | −0.96 |

| 234 | Skuy et al., 2000 | 21 | 114 | K-ABC | WISC-R | −2.13 |

| 235 | Skuy et al., 2000 | 35 | 100.8 | K-ABC | WISC-R | −0.38 |

| 236 | Smith, 1983 | 35 | 247.2 | WAIS-R | WAIS | −0.21 |

| 237 | Smith, 1983 | 35 | 247.2 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.51 |

| 238 | Solly, 1977 | 12 | 124 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.50 |

| 239 | Solly, 1977 | 12 | 124 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.43 |

| 240 | Spruill & Beck, 1988 | 23 | 306 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.37 |

| 241 | Spruill & Beck, 1988 | 35 | 306 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.19 |

| 242 | Spruill & Beck, 1988 | 25 | 306 | WAIS-R | WAIS | −0.05 |

| 243 | Spruill & Beck, 1988 | 25 | 306 | WAIS-R | WAIS | −0.24 |

| 244 | Stokes et al., 1978 | 59 | 147 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.10 |

| 245 | Swerdlik, 1978 | 100 | 108 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.23 |

| 246 | Swerdlik, 1978 | 64 | 163.2 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.20 |

| 247 | Templer et al., 1985 | 15 | 347.16 | WAIS-R | SB 60 | 0.75 |

| 248 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 75 | 66 | SB4 | WPPSI | 0.24 |

| 249 | Triggs & Cartee, 1953 | 46 | 60 | WISC | SB 32 | 1.06 |

| 250 | Tuma et al., 1978 | 9 | 119 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.12 |

| 251 | Tuma et al., 1978 | 9 | 119 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.29 |

| 252 | Tuma et al., 1978 | 9 | 123 | WISC-R | WISC | −0.04 |

| 253 | Tuma et al., 1978 | 9 | 123 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.27 |

| 254 | Urbina et al., 1982 | 68 | 505.92 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.21 |

| 255 | Valencia & Rothwell, 1984 | 39 | 54.9 | MSCA | WPPSI | 0.18 |

| 256 | Valencia, 1984 | 42 | 59.5 | K-ABC | WPPSI | −0.10 |

| 257 | Walters & Weaver, 2003 | 20 | 278.4 | WAIS-III | KBIT | −0.51 |

| 258 | Wechsler, 1955 | 52 | 252 | WAIS | SB 32 | 0.23 |

| 259 | Wechsler, 1974 | 40 | 203 | WISC-R | WAIS | 0.33 |

| 260 | Wechsler, 1974 | 50 | 72 | WISC-R | WPPSI | 0.34 |

| 261 | Wechsler, 1981 | 72 | 474 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.30 |

| 262 | Wechsler, 1989 | 61 | 63.5 | WPPSI-R | WPPSI | 0.50 |

| 263 | Wechsler, 1989 | 83 | 63.5 | WPPSI-R | WPPSI | 0.20 |

| 264 | Wechsler, 1989 | 93 | 62.5 | WPPSI-R | MSCA | 0.14 |

| 265 | Wechsler, 1989 | 59 | 61 | WPPSI-R | K-ABC | 0.9 |

| 266 | Wechsler, 1999 | 176 | 137.52 | WASI | WISC-III | 0.02 |

| 267 | Weider et al., 1951 | 44 | 77.5 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.47 |

| 268 | Weider et al., 1951 | 62 | 119.5 | WISC | SB 32 | 0.00 |

| 269 | Weiner & Kaufman, 1979 | 46 | 110 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.32 |

| 270 | Wheaton et al., 1980 | 25 | 119.76 | WISC-R | WISC | −0.01 |

| 271 | Wheaton et al., 1980 | 25 | 116.16 | WISC-R | WISC | 0.36 |

| 272 | Whitworth & Gibbons, 1986 | 25 | 252 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.18 |

| 273 | Whitworth & Gibbons, 1986 | 25 | 252 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.30 |

| 274 | Whitworth & Gibbons, 1986 | 25 | 252 | WAIS-R | WAIS | 0.21 |

| 275 | Whitworth & Chrisman, 1987 | 30 | 58 | K-ABC | WPPSI | 0.35 |

| 276 | Whitworth & Chrisman, 1987 | 30 | 58 | K-ABC | WPPSI | 0.13 |

| 277 | Woodcock et al., 2001 | 150 | 117.5 | WJTCA-III | WISC-III | 0.57 |

| 278 | Woodcock et al., 2001 | 122 | 120.6 | WJTCA-III | DAS | 0.42 |

| 279 | Yater et al., 1975 | 20 | 80.5 | WPPSI | WISC | −0.11 |

| 280 | Yater et al., 1975 | 20 | 63.45 | WPPSI | WISC | 0.23 |

| 281 | Yater et al., 1975 | 20 | 68.15 | WPPSI | WISC | −0.24 |

| 282 | Zimmerman & Woo-Sam, 1974 | 22 | 72 | SB 72 | WPPSI | −0.01 |

| 283 | Zimmerman & Woo-Sam, 1974 | 22 | 66 | SB 72 | WPPSI | −0.5 |

| 284 | Zins & Barnett, 1984 | 40 | 111 | K-ABC | SB 72 | 0.28 |

| 285 | Zins & Barnett, 1984 | 40 | 111 | K-ABC | WISC-R | 0.58 |

| Modern < 5cc | ||||||

| 286 | Brooks, 1977 | 30 | 96 | WISC | SB 72 | −7.76 |

| 287 | Carvajal et al., 1991 | 51 | 68.4 | WPPSI | SB4 | 2.36 |

| 288 | Carvajal et al., 1993 | 32 | 123 | WISC-III | SB4 | −0.74 |

| 289 | Klanderman et al., 1985 | 41 | 102 | WISC-R | SB 72 | 6.16 |

| 290 | Lavin, 1996 | 40 | 127.2 | WISC-III | SB4 | 0.28 |

| 291 | Lukens & Hurrell, 1996 | 31 | 161 | WISC-III | SB4 | 2.05 |

| 292 | McCrowell & Nagle, 1994 | 30 | 60 | WPPSI-R | SB4 | 0.63 |

| 293 | Obrzut et al., 1987 | 29 | 114.96 | WISC-R | SB 72 | 17.2 |

| 294 | Prewett & Matavich, 1994 | 73 | 116 | WISC-III | SB4 | 2.23 |

| 295 | Rust & Lindstrom, 1996 | 57 | 111.6 | WISC-III | SB4 | −0.37 |

| 296 | Sewell & Manni, 1977 | 33 | 84 | WISC-R | SB 72 | 7.4 |

| 297 | Sewell & Manni, 1977 | 73 | 144 | WISC-R | SB 72 | 5.08 |

| 298 | Simpson et al., 2002 | 20 | 108 | WISC-III | SB4 | 1.86 |

| 299 | Simpson et al., 2002 | 20 | 111 | WISC-III | SB4 | 0.88 |

| 300 | Wechsler, 1974 | 29 | 114 | WISC-R | SB 72 | 6.8 |

| 301 | Wechsler, 1974 | 27 | 150 | WISC-R | SB 72 | 6.8 |

| 302 | Wechsler, 1974 | 29 | 198 | WISC-R | SB 72 | −8.4 |

| 303 | Wechsler, 1974 | 33 | 72 | WISC-R | SB 72 | 10 |

| 304 | Wechsler, 1989 | 115 | 70 | WPPSI-R | SB4 | 0.69 |

| 305 | Wechsler, 1991 | 188 | 72 | WISC-III | WPPSI-R | −4 |

| 306 | Wechsler, 2003 | 254 | 132 | WISC-IV | WASI | 0.85 |

| 307 | Wechsler, 2008 | 141 | 198 | WAIS-IV | WISC-IV | 0.28 |

| 308 | Zins & Barnett, 1984 | 40 | 111 | WISC-R | SB 72 | −10.24 |

| Other < 5dd | ||||||

| 309 | Arffa et al., 1984 | 60 | 55 | WJTCA | SB 72 | −0.86 |

| 310 | Arinoldo, 1982 | 20 | 93 | WISC-R | MSCA | −6.5 |

| 311 | Axelrod, 2002 | 72 | 644.4 | WASI | WAIS-III | −0.98 |

| 312 | Barclay, 1969 | 50 | 63.84 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 1.51 |

| 313 | Bracken et al., 1984 | 99 | 143 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 2.14 |

| 314 | Bracken et al., 1984 | 37 | 143 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 1.44 |

| 315 | Coleman & Harmer, 1985 | 54 | 108 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 1.32 |

| 316 | Davis, 1975 | 53 | 69 | SB 72 | MSCA | 0.4 |

| 317 | Davis & Walker, 1977 | 51 | 97 | WISC-R | MSCA | −1.6 |

| 318 | Dumont et al., 2000 | 81 | 148 | DAS | WJTCA-Ree | −2.8 |

| 319 | Elliot, 1990 | 62 | 63 | DAS | WPPSI-R | 10.8 |

| 320 | Elliot, 1990 | 23 | 54 | DAS | WPPSI-R | 5.6 |

| 321 | Elliot, 1990 | 58 | 60 | DAS | SB4 | 0.8 |

| 322 | Elliot, 1990 | 55 | 119 | DAS | SB4 | 1.16 |

| 323 | Elliot, 1990 | 29 | 103 | DAS | SB4 | 1.93 |

| 324 | Elliot, 2007 | 95 | 57.6 | DAS-IIff | WPPSI-III | 0.72 |

| 325 | Estabrook, 1984 | 152 | 120 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 1.38 |

| 326 | Fagan et al., 1969 | 32 | 65 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 1.62 |

| 327 | Gregg & Hoy, 1985 | 50 | 268.8 | WAIS-R | WJTCA | 1.06 |

| 328 | Harrington et al., 1992 | 10 | 36 | WPPSI-R | WJTCA-R | −16.4 |

| 329 | Hayden et al., 1988 | 32 | 111.6 | SB4 | K-ABC | −1.85 |

| 330 | Hendershott et al., 1990 | 36 | 48 | SB4 | K-ABC | 1.81 |

| 331 | Ingram & Hakari, 1985 | 33 | 124.8 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 0.70 |

| 332 | Ipsen et al., 1983 | 27 | 108 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 0.68 |

| 333 | Ipsen et al., 1983 | 19 | 108 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 0.65 |

| 334 | Ipsen et al., 1983 | 14 | 108 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 0.60 |

| 335 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 1993 | 79 | 204 | KAIT | SB4 | 0.14 |

| 336 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004 | 86 | 138 | K-ABC-II | WJTCA-IIIgg | −0.09 |

| 337 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004 | 56 | 138 | K-ABC-II | WISC-IV | −4.6 |

| 338 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004 | 36 | 42 | K-ABC-II | WPPSI-III | −2.8 |

| 339 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004 | 39 | 66 | K-ABC-II | WPPSI-III | −7.6 |

| 340 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004 | 80 | 136 | KBIT-II | WASIhh | 0.76 |

| 341 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004 | 62 | 512 | KBIT-II | WASI | 1 |

| 342 | Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004 | 63 | 130 | KBIT-II | WISC-IV | −1.3 |

| 343 | King & Smith, 1972 | 24 | 72 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 0.74 |

| 344 | Knight et al., 1990 | 30 | 115 | SB4 | K-ABC | 0.54 |

| 345 | Krohn & Traxler, 1979 | 22 | 39 | SB 72 | MSCA | −1.2 |

| 346 | Krohn & Traxler, 1979 | 24 | 54 | SB 72 | MSCA | −5.73 |

| 347 | Krohn & Lamp, 1989 | 89 | 59 | SB4 | K-ABC | 0.61 |

| 348 | Lamp & Krohn, 2001 | 89 | 59 | SB4 | K-ABC | 0.56 |

| 349 | Lamp & Krohn, 2001 | 72 | 81 | SB4 | K-ABC | 1.41 |

| 350 | Lamp & Krohn, 2001 | 75 | 104 | SB4 | K-ABC | 0.28 |

| 351 | Law & Faison, 1996 | 30 | 182.4 | KAIT | WISC-III | −17.4 |

| 352 | Naglieri & Harrison, 1979 | 15 | 88 | SB 72 | MSCA | 24.26 |

| 353 | Oakland et al., 1971 | 24 | 74 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 0.7 |

| 354 | Oakland et al., 1971 | 24 | 72 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 0.76 |

| 355 | Pasewark et al., 1971 | 72 | 67.11 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 0.78 |

| 356 | Phelps et al., 1984 | 55 | 188 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 0.54 |

| 357 | Prosser & Crawford, 1971 | 50 | 58 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 1.5 |

| 358 | Reeve et al., 1979 | 51 | 111 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 3.04 |

| 359 | Reilly et al., 1985 | 26 | 84 | WISC-R | MSCA | 2.5 |

| 360 | Reilly et al., 1985 | 26 | 84 | WJTCA | WISC-R | −0.65 |

| 361 | Rellas, 1969 | 26 | 76 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 3.40 |

| 362 | Roid, 2003 | 145 | 96 | SB5 | WJTCA-III | 0.46 |

| 363 | Smith et al., 1989 | 18 | 125 | SB4 | K-ABC | 0.48 |

| 364 | Thompson & Brassard, 1984 | 20 | 122.4 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 0.25 |

| 365 | Thompson & Brassard, 1984 | 20 | 120 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 2.21 |

| 366 | Thompson & Brassard, 1984 | 20 | 120 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 2.47 |

| 367 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 175 | 84 | SB4 | K-ABC | −0.09 |

| 368 | Thorndike et al., 1986 | 30 | 107 | SB4 | K-ABC | 0.4 |

| 369 | Vo et al., 1999 | 30 | 147 | KAIT | WISC-III | −1.34 |

| 370 | Vo et al., 1999 | 30 | 175 | KAIT | WISC-III | −4.28 |

| 371 | Wechsler, 1967 | 98 | 66.5 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 0.34 |

| 372 | Wechsler, 1991 | 27 | 108 | WISC-III | DAS | −2.8 |

| 373 | Wechsler, 1999 | 248 | 623.76 | WASI | WAIS-III | −0.14 |

| 374 | Ysseldyke et al., 1981 | 50 | 123 | WJTCA | WISC-R | 1.80 |

| 375 | Zimmerman & Woo-Sam, 1970 | 26 | 72 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 1 |

| 376 | Zimmerman & Woo-Sam, 1970 | 21 | 72 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 2.54 |

| 377 | Zimmerman & Woo-Sam, 1974 | 22 | 72 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 1.2 |

| 378 | Zimmerman & Woo-Sam, 1974 | 22 | 66 | WPPSI | SB 60 | 2.54 |

Age reported in months.

Modern comparisons with at least five years between test norming periods.

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales – Fourth Edition.

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales – Form L-M (1972 norms ed.).

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised.

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised.

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Third Edition.

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fourth Edition.

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Third Edition.

Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Revised.

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales – Fifth Edition.

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales – Form L-M.

Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence – Third Edition.

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Fourth Edition.

All other comparisons with at least five years between test norming periods.

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children.

McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities.

Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence.

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales – Form L.

Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test.

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.

Differential Ability Scales.

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales – Form L-M (1960).

Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children.

Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities.

Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test – Second Edition.

Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children – Second Edition.

Kaufman Adolescent and Adult Intelligence Test.

Modern comparisons with less than five years between test norming periods.

All other comparisons with less than five years between test norming periods.

Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities-Revised.

Differential Ability Scales – Second Edition.

Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities – Third Edition.

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence.

Overall Model